Abstract

This study examines short- and long-term inflation expectations in the unbalanced panel of the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters. We focus on dispersion of forecaster views comparing two sub-groups of survey respondents based on forecast accuracy. We then examine possible differences between regular and irregular forecasters, and assess the impacts of varying panel composition on aggregated survey information. Our analysis indicates that survey participation is not necessarily completely random, i.e., statistically independent of forecaster views or confidence levels. While the study provides evidence that aggregated survey responses are generally a reliable proxy for inflation expectations in the euro area, one should also pay attention to expectations at the micro level, especially in periods of increased forecast uncertainty.

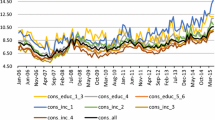

Source: Own calculations based on ECB data

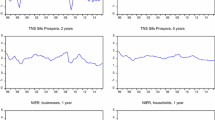

Source: Own calculations based on ECB data

Source: Own calculations based on ECB data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Conflitti (2012) and Rich et al. (2012) analyse forecast uncertainty and disagreement. Tsenova (2015) examines anchoring of long-term inflation expectations and Andrade and Le Bihan (2013) forecast revisions. The focus in Kenny et al. (2014) is on the risks assessments of forecasters and in Kenny et al. (2015) on the relationship between forecast uncertainity and forecast performance.

Overviews of the ECB SPF survey are provided in Bowles et al. (2007) and the January 2014 ECB Monthly Bulletin article “Fifteen years of the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters.” Detailed information about the survey, as well as the complete microdata set can be downloaded from http://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/prices/indic/forecast/html/index.en.html.

We assume that all the probability for a certain range relates to the mid-point of that range. Both side ranges are open-ended. In the case of the lowest (highest) open-ended range, we fix all the probability at one percentage point below (above) the left (right) end-point of that range. After the onset of the financial crisis, negative ranges were added to the inflation histograms. These new extreme values were rarely used. When they were used, the probability of a forecasted inflation outcome was typically small.

Forecast disagreement (standard deviation of point forecasts), has also been used to proxy inflation uncertainty, although in fact, it reflects polarization of individual views. Aggregated uncertainty (the standard deviation of the aggregated probability distribution) also measures forecast uncertainty. Since the variance of the aggregated probability distribution is equal to the sum of the average variance of the individual probability distributions (uncertainty of individuals) and the variance of the point estimates (disagreement), these three measures of uncertainty are closely related. Giordani and Söderlind (2003), in considering the possible impacts of outliers on the standard deviation of point forecasts, propose a quasi-standard deviation for point forecasts. This is constructed by taking half of the difference between 84th and 16th percentiles of point forecasts. Forecast uncertainty can also be measured by combined forecast uncertainty (see Giordani and Söderlind 2003) which is the average variance of individual distributions (uncertainty of individuals) minus the variance of the point estimates (disagreement). Combined forecast uncertainty is not defined, if the variance of the point estimates is larger than the average variance of the individual distribution.

Each percentile indicates the value below which a certain percentage of expectations fall. Median represents a consensus measure (50% of expectations are below median value) and the difference between 75th and 25th percentiles measures how expectations are dispersed in the middle of the distribution.

Bowles et al. (2010) note that the performance of the ECB SPF in the Q3 round is not noticeably different from other quarters.

The special questionnaire reveals that short-term inflation expectations are typically based on reduced-form models, such as single equation, vector autoregressive (VAR), or vector error correction (VEC) models. As regards long-run inflation, over 80% of short-term forecasts are judgement-based or model-based. With judgmental adjustments, 81% follow the ECB inflation target, and 54% follow trends in actual inflation. Financial market indicators, trends in wage growth and other forecast surveys are all used by 30% and fiscal indicators by 20% of forecasters in forecasting inflation 4–5 years ahead.

When comparing medians of long run PCE inflation forecasts and their ranges, Nechio (2015) removes the top and bottom 10% of survey respondents.

We continue our analysis of regular and irregular forecasting in the next section, where we focus on changing panel composition and aggregated forecasts.

The low correlation between accurate and inaccurate forecasters and the group of all forecasters in Table 3 reflects the low numbers of survey responses in some quarters (the division of forecasters into two groups is based on average RMSEs of the full sample).

See Tanizaki (2004) for a description of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

In the previous section, we analysed the groups \( N_{t} (1,1) \) and \( N_{t} (0,1) \), i.e., regular and irregular forecasters.

References

Abel, J., Rich, R., Song, J., & Tracy, J. (2016). The measurement and behavior of uncertainty: Evidence from the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 31, 533–550.

Anderson G., & Maule B. (2014). Assessing the risk to inflation from inflation expectations. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 54(2), 148–162.

Andrade, P., & Le Bihan, H. (2013). Inattentive professional forecasters. Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(8), 967–982.

Bowles, C., Friz, R., Genre, V., Kenny, G., Meyler, A., & Rautanen, T. (2007). The ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters: A review after eight years’ experience. ECB Occasional Paper 58.

Bowles, C., Friz, R., Genre, V., Kenny, G., Meyler, A., & Rautanen, T. (2010). An evaluation of the growth and unemployment forecasts in the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters. OECD Journal: Journal of Business Cycle Measurement and Analysis, 2, 63.

Conflitti, C. (2012). Measuring uncertainty and disagreement in the European Survey of Professional Forecasters. OECD Journal: Journal of Business Cycle Measurement and Analysis, 2, 69–103.

ECB. (2014). Results of the second special questionnaire for participants in the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/prices/indic/forecast/html/index.en.html.

Engelberg, J., Manski, C., & Williams, J. (2011). Assessing the temporal variation of macroeconomic forecasts by a panel of changing composition. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 26, 1059–1078.

Giordani, P., & Söderlind, P. (2003). Inflation forecast uncertainty. European Economic Review, 47, 1037–1059.

Jain, M. (2017). Perceived inflation persistence. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics (forthcoming).

Kenny, G., Kostka, T., & Masera, F. (2014). How informative are the subjective density forecasts of macroeconomists? Journal of Forecasting, 33(3), 163–185.

Kenny, G., Kostka, T., & Masera, F. (2015). Density characteristics and density forecast performance: A panel analysis. Empirical Economics, 48(3), 1203–1231.

López-Pérez, V. (2016a). Macroeconomic forecast uncertainty in the euro area. Equilibrium: Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 11(1), 9–41.

López-Pérez, V. (2016b). Does uncertainty affect non-response to the European Central Bank’s Survey of Professional Forecasters? Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 10(25), 1–46.

Nechio, F. (2015). Have long-term inflation expectations declined? (p. 11). No: FRBSF Economic Letter.

Rich, R., Song, J., & and Tracy, J. (2012). The measurement and behavior of uncertainty: Evidence from the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports 588.

Tanizaki, K. (2004). Computational methods in statistics and economics. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker.

Tsenova, T. (2015). Are long-term inflation expectations well-anchored? Evidence from the euro area and the United States. Bulletin of Economic Research, 67(1), 65–82.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this study are not necessarily those of the Bank of Finland. The authors would like to thank Michael Graff and two anonymous Referees for useful comments. They gratefully acknowledge helpful suggestions received at the Finnish Economic Association XXXVI Annual Meeting (Kuopio, Finland 2014) and the BCRC Berlin Conference (Berlin, Germany 2014). Special thanks also to participants of the 32nd CIRET Conference “Economic Tendency Surveys and Economic Policy” (Hangzhou, China, 2014) and the 9th Computational and Financial Econometrics Conference (London, UK 2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oinonen, S., Paloviita, M. How Informative are Aggregated Inflation Expectations? Evidence from the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters. J Bus Cycle Res 13, 139–163 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-017-0017-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-017-0017-6