Abstract

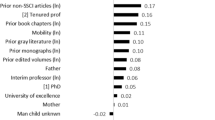

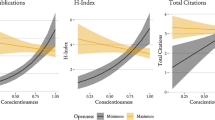

What contributes toward academic productivity and impact in political science research publications? To consider this issue, Part I of this article describes the core concepts and their operationalization, using the h-index. The study theorizes that variations in this measure may plausibly be influenced by personal characteristics (like gender, career longevity, and formal qualifications), working conditions (academic rank, type of department, and job security), as well as subjective role perceptions (exemplified by the perceived importance of scholarly research or teaching). Part II sets out new evidence used for exploring these issues, drawing upon the ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science survey. This study gathered information from 2446 political scientists in 102 countries around the globe. Part III presents the distribution and analysis of the results, as well as several robustness tests. Part IV summarizes the key findings and considers their broader implications. In general, several personal characteristics and structural working conditions prove significant predictors of h-index scores, whereas motivational goals and role perceptions add little, if anything, to the models. Thus, who you are and where you work seems to predict productivity and impact more than career ambitions and social psychological orientations toward academic work.

Source: ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science survey, Spring 2019

Source: ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science survey, Spring 2019

Source: ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science survey, Spring 2019

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See the list here: http://www.skytteprize.com/.

According to this multidisciplinary comparison, Michel Foucault is ranked as the highest rated scholar, with an h-index of 289 and 944,701 total citations. https://www.webometrics.info/en/hlargerthan100.

InCites Essential Science Indicators.

The ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science questionnaire and dataset is available from Dataverse.

See https://trip.wm.edu/.

References

Abritis, A., and A. McCook. 2017. Cash bonuses for peer-reviewed papers go global. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.357.6351.541.

Amjad, T., Y. Rehmat, and A. Daud. 2020. Scientific impact of an author and role of self-citations. Scientometrics 122 (2): 915–932.

Andersen, J., P. Nielsen, and M. Wullum. 2018. Google scholar and web of science: Examining gender differences in citation coverage across five scientific disciplines. Journal of Informetrics 12 (3): 950–959.

Bar-Ilan, J. 2008. Which h-index? A comparison of WoS, Scopus and Google Scholar. Scientometrics 74 (2): 257–271.

Barnes, C. 2014. The emperor’s new clothes: The h-index as a guide to resource allocation in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 36: 456–470.

Bernauer, T., and F. Gilardi. 2010. Publication output of swiss political science departments. Swiss Political Science Review 16 (2): 279–303.

Bornmann, L., R. Mutz, and S. Hug. 2011. A multilevel meta-analysis of studies reporting correlations between the h-index and 37 different h-index variants. Journal of Informetrics 5 (3): 346–359.

Brainard, J. and J. You. 2018. What a massive database of retracted papers reveals about science publishing’s death penalty. Science. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/10/what-massive-database-retracted-papers-reveals-about-science-publishing-s-death-penalty.

Cameron, E.Z., A.M. Gray, and M.E. White. 2016. Solving the productivity and impact puzzle: Do men outperform women, or are metrics biased? BioScience 66 (3): 245–252.

Carr, P.L., A.S. Ash, and R.H. Friedman. 2008. Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Annals of Internal Medicine 129 (7): 532–540.

Coleman, A.M., D. Dhillon, and B. Coulthard. 1995. A bibliometric evaluation of the research performance of British university politics departments: Publications in leading journals. Scientometrics 32: 49–66.

Costas, R., T.N. van Leeuwen, and M. Bordons. 2010. A bibliometric classificatory approach for the study and assessment of research performance at the individual level: The effects of age on productivity and impact. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61: 1564–1581.

Dale, T., and S. Goldfinch. 2005. Article citation rates and productivity of Australasian political science units 1995–2002. Australian Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 425–434.

Dion, M.L., L. Sumner, J. Mitchell, and S. McLaughlin. 2018. Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields. Political Analysis 26 (3): 312–327.

Egghe, L. 2010. The Hirsch index and related impact measures. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 44 (1): 65–114.

Giles, M., and J.C. Garand. 2007. Ranking political science journals: Reputational and citation approaches. PS: Political Science and Politics 40 (4): 741–751.

Harzing, A.-W., and S. Alakangas. 2016. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 106: 787–804.

Hesli, V.L., and J.M. Lee. 2011. Why do some of our colleagues publish more than others. PS: Political Science & Politics 44 (April): 393–408.

Hill, K.Q. 2020. Research creativity and productivity in political science: A research agenda for understanding alternative career paths and attitudes toward professional work in the profession. PS-Political Science & Politics 53 (1): 79–83.

Hirsch, J.E. 2005. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (46): 16569–16572.

Hirsch, J.E., and G. Buela-Casal. 2014. The meaning of the h-index. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 14 (2): 161–164.

Hix, S. 2004. A global ranking of political science departments. Political Studies Review 2 (3): 293–313.

Hoffmann, K., S. Berg, and D. Koufogiannakis. 2014. Examining success: Identifying factors that contribute to research productivity across librarianship and other disciplines. Library and Information Research 38 (119): 13–28.

Huang, J., A.J. Gates, and R. Sinatra. 2020. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (9): 4609–4616.

Ioannidis, J.P., R. Klavans, and K.W. Boyack. 2016. Multiple citation indicators and their composite across scientific disciplines. PLoS Biology 14 (7): e1002501.

Jan, R., and R. Ahmad. 2020. H-Index and its variants: Which variant fairly assess author’s achievements. Journal of Information Technology Research 13 (1): 68–76.

Katz, R., and M. Eagles. 1996. Ranking political science departments: A view from the lower half. PS: Political Science and Politics 29 (2): 149–154.

Kim, H.J., and B. Grofman. 2019. The political science 400: With citation counts by cohort, gender, and subfield. PS: Political Science and Politics 52 (2): 296–311.

Klingemann, H.-D., B. Grofman, and J. Campagna. 1989. The political science 400: Citations by Ph.D. Cohort and by Ph.D.-Granting Institution. PS: Political Science and Politics 52 (2): 296–311.

Kreiner, G. 2016. The slavery of the h-index: Measuring the unmeasurable. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 10: 556.

Kulczycki, E., T.C. Engels, and J. Polonen. 2018. Publication patterns in the social sciences and humanities: Evidence from eight European countries. Scientometrics 116 (1): 463–486.

LaCour, M.J., and D.P. Green. 2014. When contact changes minds: An experiment on transmission of support for gay equality. Science 346 (6215): 1366–1369.

Lederman, D. 27 Nov 2019. The faculty shrinks but tilts to full-time. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/11/27/federal-data-show-proportion-instructors-who-work-full-time-rising.

Mason, M.A., N.H. Wolfinger, and M. Goulden. 2013. Do babies matter? Gender and family in the ivory tower. Newark, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Masuoka, N., B. Grofman, and S.L. Feld. 2007a. The political science 400: A twenty-year update. PS: Political Science & Politics 40 (January): 133–145.

Masuoka, N., B. Grofman, and S.L. Feld. 2007b. Ranking departments: A comparison of alternative approaches. PS: Political Science & Politics 40 (July): 531–537.

Moss-Racusin, C.A., J.F. Dovidio, V.L. Brescoll, M.J. Graham, and J. Handelsman. 2012. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 109 (41): 16474–16479.

Norris, P. 2020. The world of political science: Internationalization and its consequences. Chapter 3 in ECPR@50 Eds. Thibaud Boncourt, Isabelle Engeli, Diego Garzia. Colchester, Essex: ECPR Press.

Norris, M., and C. Oppenheim. 2010. The h-index: A broad review of a new bibliometric indicator. Journal of Documentation 66 (5): 681–705.

Panaretos, J., and C. Malesios. 2009. Assessing scientific research performance and impact with single indices. Scientometrics 81 (3): 635–670.

Petersen, A., R.K. Pan, F. Pammolli, and S. Fortunato. 2019. Methods to account for citation inflation in research evaluation. Research Policy 48 (7): 1855–1865.

Radicchi, F. 2012. In science “there is no bad publicity”: Papers criticized in comments have high scientific impact. Scientific Reports 1: 815.

Radicchi, F., S. Fortunato, and C. Castellano. 2008. Universality of citation distributions: Toward an objective measure of scientific impact. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (45): 17268–17272.

Ravenscroft, J., M. Liakata, and A. Clare. 2017. Measuring scientific impact beyond academia: An assessment of existing impact metrics and proposed improvements. PLoS ONE 12: e0173152.

Rebora, G., and M. Turri. 2013. The UK and Italian research assessment exercises face to face. Research Policy 42 (9): 1657–1666.

Robey, J.S. 1982. Reputations vs citations: Who are the top scholars in political science? PS: Political Science & Politics 15: 199–200.

Roettger, W.B. 1978. Strata and stability: Reputations of American political scientists. PS: Political Science & Politics 11 (Winter): 6–12.

Schreiber, W.E., and D.M. Giustini. 2018. Measuring scientific impact with the h-Index: A primer for pathologists. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 151 (3): 286–291.

Shin, J.C., R.K. Toutkoushian, and U. Teichler (eds.). 2011. University rankings: Theoretical basis, methodology and impacts on global higher education. New York: Springer.

Somit, A., and J. Tanenhaus. 1964. American political science: A profile of a discipline. New York: Atherton Press.

Teele, D., and K. Thelen. 2017. Gender in the journals: Publication patterns in political science. PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (2): 433–447.

Waltman, L. 2016. A review of the literature on citation impact indicators. Journal of Informetrics 10 (2): 365–391.

Waltman, L., and N.J. van Eck. 2012. The inconsistency of the h-index. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 63: 406–415.

Zheng, J., and N. Liu. 2015. Mapping of important international academic awards. Scientometrics 104: 763–791.

Acknowledgements

The ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science survey could not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of Martin Bull, Kris Deschouwer, and Rebecca Gethen at the ECPR, as well as Marianne Kneuer and Mathieu St-Laurent at IPSA, and several national associations, as well as the willingness of all colleagues to participate in the survey. Thanks are due to all involved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Source: The ECPR-IPSA World of Political Science survey, spring 2019. N.2466

Var | Measure | Question | Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

Personal characteristics | |||

V32 | Gender | What is your gender | 1 Female/0 male |

Q24 | Career longevity | In what year did you complete your highest degree? | Year (1943–2019) |

Q22 | Formal qualifications | What is the highest level of education you successfully completed? | Undergraduate degree (1), Masters or professional degree (2), doctoral degree or equivalent (3). |

Q34 | Dependents | Do you currently have responsibilities for any dependents living at home? | Additive scale from No dependents (0), yes children (1), yes elderly relatives (1) |

Working conditions | |||

V16 | Academic rank | Which of the following categories best describes the most senior position you have held? | 7-pt scale from Graduate student (1) to Senior administrative position such as PVC, Dean, Head of Faculty or School, or equivalent (7) |

V29 | Income | Please indicate your gross personal annual income before taxes and benefits | |

V12_6 | Job security | Thinking about your current employment, please indicate how true you feel each of the following statements are: My job is secure. | 4-pt scale from “Not at all true” to “Very true.” |

V17 | Contract | If in academic employment, which of the following best describes your current post? | Temporary post (no legal contract, e.g., hourly paid work) (1), fixed term contract (2), Continuous contract (tenured position(3). |

V15 | Work status | Which of the following best describes your current work status? | |

Q21 | Size of department | If currently in academic employment or studying, which of the following best describes the approximate number of FTE academic teaching and research staff in your current university or college (or past one if retired or unemployed) (excluding administrative staff). | 6-point scale from 9 or fewer (1) to 50 or more (5) |

Q22 | Size of institution | If currently in academic employment or studying, which of the following best describes the approximate number of FTE students in your current university or college (or past one if retired or unemployed). | 5-pt scale from 9000 or fewer (1) to 50,000 or more (5) |

Q2 | Highly cited society: country of work/study | In what country do you currently work or study? | Recoded (0/1) by the top 10 nations in the 2019 WoS list of countries with the most highly cited researchers across all disciplines (1) or not (0). |

Role perceptions | |||

Q6-9 | Research | How important are each of the following goals to you personally? | See Table 1 |

Q6-9 | Teaching | How important are each of the following goals to you personally? | See Table 1 |

Q6-9 | Publishing | How important are each of the following goals to you personally? | See Table 1 |

Q6-9 | Policy impact | How important are each of the following goals to you personally? | See Table 1 |

Q6-9 | Work-life balance | How important are each of the following goals to you personally? | See Table 1 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Norris, P. What maximizes productivity and impact in political science research?. Eur Polit Sci 20, 34–57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00308-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00308-4