Abstract

Political scientists are accustomed to imagining electoral politics in geographical terms. For instance, there is a “red America” that largely covers the country’s expansive heartland and there is a “blue America” mostly confined to the coasts. Until recently, however, public opinion scholars had largely lost sight of the fact that the places where people live, and people’s identification with those places, shape public opinion and political behavior. This paper develops and validates a flexible psychometric scale measure of a key political psychological dimension of place: place resentment. Place resentment is hostility toward place-based outgroups perceived as enjoying undeserved benefits beyond those enjoyed by one’s place-based ingroup. Regression results indicate that males, ruralites, younger Americans, those high in place identity, and those high in racial resentment are more likely to harbor higher levels of place resentment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this, place resentment parallels racial resentment, which encompasses both prejudices and values (e.g., Kinder and Sanders 1996, pp. 291–294), but is unidimensional empirically due to its central emotional theme.

For a thorough account, focusing on racial identity, of how shifts in the political communication environment is linked to the political potency of social identities, see Jardina (2019).

In developing my items for the place resentment scale, I consciously avoided terms to the extent possible that could be tinged with racial or class-based associations.

While Enos (2017) concerns the effects of objective spatial group arrangements, this paper deals with subjective identification with symbolic spaces and imagined geographic community. While both interact with other social considerations, including race, those relationships detailed by Enos are more determinative and less variable than those involving place-based identity.

Appreciating that space is a premium on survey modules, a truncated 4 item version of the complete 10 item measure is also analyzed in this article.

Though this paper focuses on demonstrating the usefulness of this scale for studying the role of place resentment along the urban–rural continuum, questions could easily be modified to examine place resentment attached to other place identities, such as regional identity (either nationally, e.g., Appalachia, or within states, i.e., “out-state Wisconsin”). It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore the question of level of geographic aggregation. Clearly some people identify with their urban, suburban, or rural status, while others may identify with place at other levels, such as their neighborhood, town, state, or region. Given the importance of rural identification in the accounts of Cramer and others, and the importance of urban and rural in contemporary political discourse, I focus there.

To be clear, respondents were asked to classify, in their own judgement, which type of community that they live in. In the Lucid sample, respondents chose from a 6-category item ranging from “very urban” to “very rural.” On the CCES sample, respondents selected from a 4-category measure featuring categories “urban,” “suburban,” “town,” and “rural area.”

All replication data and code for this article can be found at this link: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LZQHTK.

Lucid is a relatively new firm that provides researchers access to panels that yield high quality, nationally representative data. In a recent validation study, Coppock & McClellan (2019) find that Lucid results track well with high quality samples well-regarded by the political science community, including the American National Election Study (ANES).

All models utilizing CCES data use the weights calculated by YouGov/CCES.

Samples are also representative in terms of urban–rural: 22% in two rural-most categories in the Lucid data and 19% as “rural areas” in the CCES data.

While much existing work on affective polarization focuses on animus between partisans, Johnson-Grey’s (2018) measure focusing on animus between ideological identities (liberal v conservative) is applicable to studying affective polarization given the degree to which the parties are now sorted in terms of ideological identity (Levendusky 2009; Mason 2018).

Moreover, internal consistency is high for both urban (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82) and rural (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85) self-identifiers alike.

Confirmatory factor analysis was run in R using the laavan package (Rosseel 2012). RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

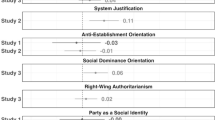

Controlling for racial resentment, populism, affective polarization, place identity strength, party ID, age, gender, and household income. Coefficients for variables of interest are presented in Table A7 in the Appendix. Only models for place resentment amongst urbanites and ruralites were possible due to the way urban-ness and ruralness were measured in the Lucid sample and because no measures of attitudes toward urbanites and ruralites were present in the 2018 CCES.

A statistically significant difference between groups was determined in both the Lucid [F(5, 15) = 33.77, p < 0.001] and CCES [F(2, 3) = 39.40, p < 0.001] samples.

References

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for Realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Agnew, J. A. (2014). Place and politics: The geographical mediation of state and society. London: Routledge.

Albertson, B., & Kushner Gadarian, S. (2017). Forum on the politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker and Anxious Politics. Political Psychology, 39(1), 229–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12462.

Bishop, B. (2009). The Big Sort: Why the clustering of like-minded America is tearing us apart. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Carmines, E. G., & Schmidt, E. R. (2017). A discussion of Katherine J. Cramer's the politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Perspectives on Politics, 15(2), 527–528.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. Critical Review, 18(1–3), 1–74.

Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822174.

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cuba, L., & Hummon, D. M. (1993a). A place to call home: Identification with dwelling, community, and region. Sociological Quarterly, 34(1), 111–131.

Cuba, L., & Hummon, D. M. (1993b). Constructing a sense of home: Place affiliation and migration across the life cycle. Sociological Forum, 8(4), 547–572.

Cutler, F. (2007). Context and attitude formation: Social interaction, default information, or local interests? Political Geography, 26(5), 575–600.

Davis, D. (2017). A discussion of Katherine J. Cramer's the politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Perspectives on Politics, 15(2), 525–526.

Dudas, J. R. (2017). A discussion of Katherine J. Cramer's the politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Perspectives on Politics, 15(2), 523–524.

Eliasoph, N. (2017). Forum book symposium: The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Political Communication, 34(1), 138–141.

Enos, R. D. (2017). The space between us: Social geography and politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fenno, R. F. (1978). Home style: House members in their districts (Longman classics series). London: Longman Publishing Group.

Fitzgerald, J. (2018). Close to home: Local ties and voting radical right in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gimpel, J. G., & Karnes, K. A. (2006). The rural side of the urban-rural gap. PS: Political Science & Politics, 39(3), 467–472.

Green, D. P., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2004). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hernández, B., Hidalgo, M. C., Salazar-Laplace, M. E., & Hess, S. (2007). Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(4), 310–319.

Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253–283.

Herschey, M. R. (2017). Forum book symposium: The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Political Communication, 34(1), 134–137.

Hidalgo, M. C., & Hernandez, B. (2001). Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 273–281.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal on Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

Hopkins, D. A. (2017). Red fighting blue: How geography and electoral rules polarize American politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Hui, I. (2013). Who is your preferred neighbor? Partisan residential preferences and neighborhood satisfaction. American Politics Research, 41(6), 997–1021.

Huddy, L. (2015). Group identity and political cohesion. Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences: An interdisciplinary, searchable, and linkable resource (pp. 1–14). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Jacobs, N. F., & Munis, B. K. (2019). Place based imagery and voter evaluations: Experimental evidence on the politics of place. Political Research Quarterly, 72(2), 263–277.

Jardina, A. (2019). White identity politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson-Grey, K. M. (2018). Expressing values and group identity through behavior and language. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Southern California.

Key, V. O. (1949). Southern politics in state and nation. New York: A.A. Knopf.

Kinder, D. R., & Kalmoe, N. P. (2017). Neither liberal nor conservative: Ideological innocence in the American public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lalli, M. (1992). Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement, and empirical findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(4), 285–303.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The Partisan sort: How liberals became Democrats and conservatives became Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Low, S. M., & Altman, I. (1992). Place attachment. In Place attachment (pp. 1–12). Boston: Springer.

Makse, T., Minkoff, S., & Sokhey, A. (2019). Politics on display: Yard signs and the politicization of social spaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miller, A. H., Gurin, P., Gurin, G., & Malanchuk, O. (1981). Group consciousness and political participation. American Journal of Political Science, 25(3), 494–511.

Millington, G. (2011). ‘Race’, culture and the right to the city: Centres, peripheries, margins. Dordrecht: Springer.

Munis, B. K. (2015). The occurrence of place-based narrative in US senatorial campaign advertisements. Unpublished MA Thesis, University of Montana.

Munis, B.K. (2020). Divided by place: The enduring geographical fault lines of American politics. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Virginia. https://doi.org/10.18130/v3-z7hw-1r58.

Nanzer, B. (2004). Measuring sense of place: a scale for Michigan. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 26(3), 362–382.

Ortony, A., Clore, G. L., & Collins, A. (1990). The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Osborne, B. S. (2006). From native pines to diasporic geese: Placing culture, setting our sites, locating identity in a transnational Canada. Canadian Journal of Communication, 31(1), 147–175.

Panagopoulos, C., Leighley, J. E., & Hamel, B. T. (2017). Are voters mobilized by a ‘friend-and-neighbor’ on the ballot? Evidence from a field experiment. Political Behavior, 39(4), 865–882.

Parker, D. C. (2014). Battle for the big sky: Representation and the politics of place in the race for the US Senate. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Phillips, K. P. (1969). The emerging republican Majority. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rhodes, J., & Brown, L. (2018). The rise and fall of the ‘inner city’: Race, space and urban policy in postwar England. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(17), 3243–3259.

Rodden, J. A. (2019). Why cities lose: The deep roots of the urban-rural political divide. New York: Basic Books.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2017). A discussion of Katherine J. Cramer's the politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Perspectives on Politics, 15(2), 529–530.

Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., & Wirth, W. (2017). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(2), 316–326.

Sides, J., Tesler, M., & Vavreck, L. (2018). Identity crisis: The 2016 presidential campaign and the battle for the meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stedman, R. C. (2002). Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environment and Behavior, 34(5), 561–581.

Steiger, J. H. (2007). Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 893–898.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of inter group behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson.

Tarman, C., & Sears, D. O. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of symbolic racism. The Journal of Politics, 67(3), 731–761.

Willis, G. B. (2004). Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wolbrecht, C. (2017). A discussion of Katherine J. Cramer's the politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Perspectives on Politics, 15(2), 521–522.

Wong, C. J. (2010). Boundaries of obligation in American politics: Geographic, national, and racial communities. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wuthnow, R. (2018). The left behind: Decline and rage in rural America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Acknowledgements

There are many people who deserve acknowledgement for making this manuscript better than it would otherwise would have been. In particular, I would like to thank Katherine Cramer, Nicholas Winter, Paul Freedman, Lynn Sanders, Justin Kirkland, Jonathan Kropko, Olyvia Christley, Nicholas Jacobs, Richard Burke, Anthony Sparacino, Rachel Smilan-Goldstein, Tyler Syck, Jordan Cash, Paul Goren, Princess Williams, and the anonymous reviewers for their insights.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Munis, B.K. Us Over Here Versus Them Over There…Literally: Measuring Place Resentment in American Politics. Polit Behav 44, 1057–1078 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09641-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09641-2