Abstract

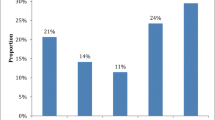

For most of Canadian economic history, French-Canadians (who composed more than a quarter of the country’s population) had living standards inferior to those of English-Canadians. This was true even within the province of Quebec, where the French-Canadians constituted a majority. Today, no significant gap remains in Quebec. Surprisingly however, the question of when the gap started to disappeared remains unanswered. Most of the attention has been dedicated to the long-available post-1970 census data, which show rapid convergence. However, it is unknown whether the convergence started before 1970. In this paper, we use more recently uncovered data from the censuses between 1901 and 1951 to provide such an answer. We find that there was convergence from 1901 to 1921, a reversal from 1921 to 1941 and a recovery between 1941 and 1951 that extended to 1971.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Moreover, French-Canadians in Quebec also exhibited the same average number of years of schooling as African-Americans in 1961 (Fortin 2011).

It must be noted that the comparison with Black Americans was also very common in Quebec as early as the 1910s. Its use by nationalist figures was meant to highlight the relative poverty of francophones while also invoking an image of a lower political status. This potent imagery was increasingly used to justify greater political autonomy for Quebec.

We also know that labor markets are no longer segmented along linguistic lines (largely because of high rates of bilingualism—see Lepage and Corbeil (2013)). Quebec’s multilingual labor markets today appear to be well integrated (Vaillancourt et al. 2013) in a manner similar to other multilingual societies such as Switzerland (Cattaneo and Winkelmann 2005). We do not know, however, when the segmentation began to erode.

The summary form is explained by the fact that the microdata from the 1961 census have been lost. This is why most economists start with the 1971 census when evaluating the wage gap. The earliest one can go is 1969 by using the Family and Expenditures Survey (Geloso 2017) which has a considerably smaller sample.

The one exception was the work of McKinnon (2000) which found a sizable wage gap in 1901 (however, her sample concerned Montreal only).

The sample for 1901 was digitized by the Canadian Families Project (CFP). The data are available to the public at http://web.uvic.ca/hrd/cfp/data/index.html. The samples for 1911 and 1921 censuses were digitized by the Canadian Century Research Infrastructure (CCRI). These data are publicly available at https://ccri.library.ualberta.ca/enindex.html.

Starting in 1901, the first census schedule had two columns for “earnings from occupation or trade” and “extra earnings (from other than chief occupation or trade.”

There are no options available to estimate hourly earnings.

The census also asked, if Canada was reported as place of birth, what province the person was born in. This could allow us to exclude individuals not from Quebec, but we will not make this exclusion as we are interested in the linguistic wage gap between French-Canadians and English-Canadians in Quebec regardless of place of birth.

We use age and five power terms as per the specification proposed by McKinnon (2000). Her justification for using \(age^5\) was drawn from the work of Hatton (1997) whereby late nineteenth century and early twentieth century age earnings profile did not tend to follow the more modern profile approximated by the use of age and its square. Thus, using merely a quadratic term risks misspecification of the model. We followed the specification found by McKinnon (2000) to have some form of external validity to our results when we regress only for Montreal (see more below).

The censuses contained more than 400 occupations. Following the specifications of Edwards (1940); Chiswick (1991); Dilmaghani and Dean (2018), we broke down these occupations into nine categories that form our dummy variables for occupational activity: (1) professional and semi-professional; (2) proprietors, managers, and officials; (3) clerical, sales, and kindred; (4) craftsmen and foreman; (5) operatives; (6) protective service; (7) other service; (8) apprentice and; (9) laborer (which forms the reference category).

Because of the different structure of the census questions with regard to education and the issues associated with the 1911 census (see more below), we eschew the option of pooling the different cross-sections and using an interaction between year and francophone to capture the evolution.

The CFP and CCRI are stratified random samples of individual records by dwelling. See https://ccri.library.ualberta.ca/endatabase/sampling/sampledesign/ for a more detailed discussion.

While André Raynauld’s data apply to the 1950s, Montreal represented 41% of the province’s manufacturing employment. In contrast, Ontario’s largest city, Toronto, represented 21% of that province’s manufacturing employment (Raynauld 1961, 381).

For 1901, the following Census districts were used to identify Montréal: 155, 167, 174-178. Urban areas are defined as all villages, towns, and cities with a population of 1,000 or more. For 1911-1951, Montréal is identified using information on the Census subdivision name. As per the Census Bureau classification, urban areas refer to incorporated cities, towns and villages with other types being classified as rural. However, in 1951, the Census Bureau changed its rural classification to include all persons residing in cities, towns and villages of 1000 and over, whether incorporated or unincorporated.

Foreign-born English or French speakers were not to be marked as English or French.

In fact, to this day, Statistics Canada refuses to report the linguistic data for 1911—see, for example, the study of Lepage and Corbeil (2013).

See Tables 2 to 13 in the online supplement available at https://vincentgeloso.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/clioappendix.xlsx.

The percentage impact of LinguisticStatus (because earnings are logged) is calculated using 100*[exp(\(\beta _1\)) - 1] as proposed by Halvorsen and Palmquist (1980).

The reversal appears to start after the 1911 census. However, we are reluctant to make any inference from this as Gaffield et al. (2014) highlight the numerous limitations that could be biasing our coefficients for 1911. Moreover, our reversal during the Depression is consistent with those of Inwood et al. (2016) regarding immigrants in Canada during the Great Depression. They find that the convergence observed to 1921 was reversed with the Depression. Immigrant workers are more likely to represent the marginal worker and thus be adversely affected by the contraction. French-Canadians, by virtue of their lower levels of human capital, are also probably more representative of the marginal worker. Thus, the Depression appears as a more economically relevant point for a reversal of (relative) fortunes.

This is especially true when we follow her exact model specification that included the foreign-born and their religion. This suggests that the issue of the sample size for Montreal is of minimal concern.

See table 15 in the online supplement.

The specification they use is slightly different from ours. Most notably, they are able to use hourly earnings rather than weekly earnings (the only measure we can use for the pre-1951 period) and they use a measure of potential experience which we cannot use (for lack of an education variable pre-1941—which is why we used different powers of age as controls for experience instead). As such, we have to alter the specification in their paper to be comparable with our data. We thank David Albouy for sharing the data he used in his 2008 article and Maripier Isabelle for sharing the code file for the same data used in her 2020 article.

Vaillancourt (1988) made a similar finding earlier but with fewer data.

Raynauld and Marion (1972) had made a similar proposition in the 1970s but using different theoretical tools and without any econometric testing.

This is largely because very few anglophones did not know how to read and write. The small number of observation makes estimation daunting. Moreover, the ability to read and write captures only an elementary aspect of education (i.e., whether a person had some education) but it does not capture the depth of human capital (i.e., how many years of schooling a person achieved).

For the full set of regression results, see tables 15a and 15b in the online supplement.

Additional research using data from the Quebec Department of Education (which have never yet been digitized) could help understand the role of educational policy in the period.

References

Albouy D (2008) The wage gap between Francophones and Anglophones: a Canadian perspective, 1970–2000. Canad J Econ 41(4):1211–1238

Altman M (1998) Land tenure, ethnicity, and the condition of agricultural income and productivity in mid-nineteenth-century Quebec. Agric History 72(4):708–762

Arsenault-Morin A, Geloso V, Kufenko V (2017) The heights of French-Canadian convicts, 1780s–1820s. Econ Human Biol 26:126–136

Baker M, Hamilton G (2000) Écarts salariaux entre francophones et anglophones à Montréal au 19e siècle. L’Actualité économique 76(1):75–111

Bélanger Y, Fournier P (1987) L’entreprise québécoise: développement historique et dynamique contemporaine, vol 90. Éditions Hurtubise HMH

Bleakley H, Chin A (2008) What holds back the second generation? The intergenerational transmission of language human capital among immigrants. J Human Resour 43(2):267–298

Bock M (2017) De l’anti-impérialisme à la décolonisation: La transformation paradigmatique du nationalisme québécois et la valeur symbolique de la Confédération canadienne (1917–1967). Histoire, economie societe 36(4):28–53

Bouchette E (1913) L’indépendance économique du Canada français. Wilson & Lafleur

Breton A (1964) The economics of nationalism. J Political Econ 72(4):376–386

Breton A (1978a) Bilingualism: an economic approach. CD Howe Research Institute

Breton A (1978b) Nationalism and language policies. Canad J Econ, pp 656–668

Brown WM, Macdonald R et al (2015) Provincial convergence and divergence in Canada. Statistics Canada-Statistique Canada (1926 to 2011)

Caldwell C, Czarnocki B (1977) Un rattrapage raté Le changement social dans le québec d’après-guerre, 1950–1974: Une comparaison Québec/Ontario. Recherches sociographiques 18(1):9–58

Cattaneo A, Winkelmann R (2005) Earnings differentials between German and French speakers in Switzerland. Swiss J Econ Statistics 141(2):191–212

Chiswick BR (1991) Jewish immigrant skill and occupational attainment at the turn of the century. Explorat Econ History 28(1):64–86

Chiswick BR, Miller PW (1996) Ethnic networks and language proficiency among immigrants. J Populat Econ 9(1):19–35

Chiswick BR, Miller PW (2003) The complementarity of language and other human capital: immigrant earnings in Canada. Econ Educat Rev 22(5):469–480

Chung J (1974) La nature du déclin économique de la région de Montréal. L’ Actualité économique 50(3):326–341

Cranfield J, Inwood K (2007) The great transformation: a long-run perspective on physical well-being in Canada. Econ Human Biol 5(2):204–228

Dilmaghani M, Dean J (2018) Labor market attainment of Canadian Jews during the first two decades of the 20th century. Contemporary Jewry 38(1):49–77

Duchesne L (1977) Analyse descriptive du bilinguisme au Québec selon la langue maternelle en 1951, 1961, 1971. Cahiers québecois de démographie 36(2):33–65

Duffy J, Papageorgiou C, Perez-Sebastian F (2004) Capital-skill complementarity? Evidence from a panel of countries. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):327–344

Durocher R, Linteau PA (1971) Le “retard” du Québec et l’infériorité économique des Canadiens français. Éditions Boréal express

Dustmann C, Fabbri F (2003) Language proficiency and labour market performance of immigrants in the UK. Econ J 113(489):695–717

Edwards AM (1940) Alphabetical index of occupations and industries. US Government Printing. Office

Egnal M (1996) Divergent paths: how culture and institutions have shaped North American growth. Oxford University Press

Emery JH, Levitt C (2002) Cost of living, real wages and real incomes in thirteen Canadian cities, 1900–1950. Canad J Econ Revue canadienne déconomique 35(1):115–137

Fallon PR, Layard PRG (1975) Capital-skill complementarity, income distribution, and output accounting. J Political Econ 83(2):279–302

Fortin P (2001) Has Quebec’s standard of living been catching up? Centre for the study of living standards, pp 381–402

Fortin P (2011) La Révolution tranquille et léconomie: Oú étions-nous, que vivions-nous et quavons-nous accompli? In: Berthiaume G, Corbo C (eds) La Révolution Tranquille en Héritage. Boréal, pp 87–134

Fournier J (2005) Les économistes canadiens-français pendant lentre-deux-guerres: entre la science et lengagement. Revue dhistoire de lAmérique française 58(3):389–414

Gaffield C (2016) Language, Ancestry, and the Competing Constructions of Identity in Turn-of-the-Century Canada. Household Counts, vol 13. University of Toronto Press, pp 423–440

Gaffield C, Moldofsky B, Rollwagen K (2014) Do Not Use for Comparison with Other Censuses: Identity, Politics, and Languages Commonly Spoken in 1911 Canada. In: Darroch G, (ed) The Dawn of Canada’s Century: Hidden Histories, pp 93–123

Gagnon R (1996) Histoire de la Commission des écoles catholiques de Montréal: le développement d’un réseau d’écoles publiques en milieu urbain. Boréal

Gagnon A (1997) Duplessis-Entre la Grande Noirceur et la société libérale. Québec Amerique

Gagnon J, Geloso V, Isabelle M (2020) The Incubated Revolution: Education, Cohort Effects, and the Linguistic Wage Gap in Quebec, 1970 to 2000. Technical report

Geloso V (2017) Rethinking Canadian Economic Growth and Development since 1900: The Case of Québec. Studies in Economic History, Palgrave

Geloso VJ (2019) Distinct within North America: living standards in French Canada, 1688–1775. Cliometrica 13(2):277–321

Geloso V, Belzile G (2018) Electricity in Quebec before Nationalization, 1919 to 1939. Atlantic Econ J 46(1):101–119

Geloso V, Macera G (2020) How Poor Were Quebec and Canada During the 1840s? Social Science Quarterly 101(2):792–810

Geloso V, Kufenko V, Prettner K (2016) Demographic change and regional convergence in Canada. Econ Bull 36(4):1904–1910

Green AG (1971) Regional aspects of Canada’s economic growth. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Grenier G (1987) Earnings by Language Group in Quebec in 1980 and Emigration from Quebec between 1976 and 1981. Canad J Econ 20(4):774–791

Halvorsen R, Palmquist R et al (1980) The interpretation of dummy variables in semilogarithmic equations. Am Econ Rev 70(3):474–475

Hatton T (1997) The immigrant assimilation puzzle in late Nineteenth-Centuty America. J Econ History 57(1):34–62

Inwood K, Minns C, Summerfield F (2016) Reverse assimilation? Immigrants in the Canadian labour market during the great depression. Europ Rev Econ History 20(3):299–321

Lamonde Y (2000) Histoire sociale des idées au Québec: 1760–1896, vol 1. Les Editions Fides

Laurendeau A, Dunton D (1969) Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, Vol. 3. Office of the Privy Council

Lepage J-F, Corbeil J-P (2013) L’évolution du bilinguisme français-anglais au Canada de 1961 à 2011. Statistics Canada

Lewis F, McInnis M (1984) Agricultural output and efficiency in lower Canada, 1851. Res Econ History 9:45–87

McInnis RM (1992) Perspectives on Ontario agriculture. Langdale Press, Ontario

McKinnon M (2000) Unilingues ou bilingues? Les Montréalais sur le marché du travail en 1901. Actualité Économique 76(1):137–158

McRoberts K (1988) Quebec: social change and political crisis. McClelland & Stewart

Migué JL (1998) Étatisme et déclin du Québec: bilan de la Révolution tranquille. Editions Varia

Nadeau S (2010) Another look at the francophone wage gap in Canada: public and private sectors, Québec and outside Québec. Canad Public Policy 36(2):159–179

Ornstein M (2000) Analysis of household samples: the 1901 census of Canada. Historical Methods J Quant Interdiscip History 33(4):195–198

Paquet G (1999) Oublier la Révolution tranquille: pour une nouvelle socialité. Liber Montréal

Pendakur K, Pendakur R (2002) Language as both human capital and ethnicity. Int Migration Rev 36(1):147–177

Polèse M (1990) La thèse du déclin économique de Montréal, revue et corrigée. Lé économique 66(2):133–146

Raynauld A (1961) Croissance et structure économiques de la province de Québec. Ministère de l’industrie et du commerce

Raynauld A, Marion G (1972) Une analyse économique de la disparité inter-ethnique des revenus. Revue économique 23(1):1–19

Shapiro D, Stelcner M (1981) Male–Female earnings differentials and the role of language in Canada, Ontario, and Quebec. Canad J Econ 14(2):341–348

Shapiro D, Stelcner M (1997) Language and earnings in Quebec: trends over twenty years, 1970–1990. Canad Public Policy 23(2):115–140

Stewart MB (1983) On least squares estimation when the dependent variable is grouped. Rev Econ Stud 50(4):737–753

Taylor NW (1960) The effects of industrialization-its opportunities and consequences-upon french-Canadian society. J Econ History 20(4):638–647

Vaillancourt F (1988) Langue et disparités de statut économique au Québec, 1970 et 1980. Conseil supérieur de langue française

Vaillancourt F, Vaillancourt L (2005) La propriété des employeurs au Québec en 2003 selon le groupe d’appartenance linguistique. Conseil supérieur de langue française

Vaillancourt F, Dominique L, Vaillancourt L (2007) Laggards no more: the changed socioeconomic status of Francophones in Queébec. Backgrounder 103. C.D.Howe Institute

Vaillancourt F, Tousignant J, Chatel-DeRepentigny J, Coutu-Mantha S (2013) Revenus de travail et rendement des attributs linguistiques au Québec en 2005 et depuis 1970. Canadian Public Policy, 39(Special Supplement of Income, Inequality and Immigration):S25–S40

Vallières P (1968) Nègres blancs d’Amérique: autobiographie précoce d’un terroriste québécois. FeniXX

Verrette M (1985) LAétisation de la population de la ville de Québec de 1750 à 1849. Revue d de lrique française 39(1):51–76

Young RA (1994) The political economy of secession: the case of Quebec. Constitut Political Econ 5(2):221–245

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dean, J., Geloso, V. The linguistic wage gap in Quebec, 1901 to 1951. Cliometrica 16, 615–637 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-021-00236-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-021-00236-3