Abstract

Since the announcement and establishment of the Oversight Board (OB) by the technology company Meta as an independent institution reviewing Facebook and Instagram’s content moderation decisions, the OB has been subjected to scholarly scrutiny ranging from praise to criticism. However, there is currently no overarching framework for understanding the OB’s various strengths and weaknesses. Consequently, this article analyses, organises, and supplements academic literature, news articles, and Meta and OB documents to understand the OB’s strengths and weaknesses and how it can be improved. Significant strengths include its ability to enhance the transparency of content moderation decisions and processes, to effect reform indirectly through policy recommendations, and its assertiveness in interpreting its jurisdiction and overruling Meta. Significant weaknesses include its limited jurisdiction, limited impact, Meta’s control over the OB’s precedent, and its lack of diversity. The analysis of a recent OB case in Ethiopia shows these strengths and weaknesses in practice. The OB’s relationship with Meta and governments will lead to challenges and opportunities shaping its future development. Reforms to the OB should improve the OB’s control over its precedent, apply OB precedent to currently disputed cases, and clarify the standards for invoking OB precedent. Finally, these reforms provide the foundation for an additional improvement to address the OB’s institutional weaknesses, by involving users in determining whether the OB’s precedent should be applied to decide current content moderation disputes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since its founding, Facebook has become critical for online expression and communication globally, with free expression a core value for the platform. However, controversies—from interethnic conflict to online disinformation—have exposed the real-world consequences of how Facebook and other social media platforms moderate content. Citing the flaws of platforms’ content moderation, some governments have attempted to regulate content on social media platforms. However, authoritarian governments may clamp down on dissenters or silence underrepresented groups, while even well-intentioned democratic governments risk inadvertently chilling the dissent that is integral to a free society. Subjecting platforms’ content moderation decisions to judicial review may be expensive and time-consuming, given the speed and scale at which social media platforms moderate content. It may also discriminate against poorer users who lack the resources or time to litigate such a lawsuit.

Given the challenge of improving content moderation on social media platforms, Meta’s establishment of an independent institution named the Oversight Board (OB) to review Facebook and Instagram’s content moderation decisions represents an interesting development. Legally independent from Meta, the OB issues binding decisions on content moderation decisions on Facebook and Instagram and issues non-binding recommendations regarding platform policies.

Since the OB was first announced in late 2018 and began issuing decisions in early 2021, it has been subjected to various scholarly assessments. Supporters have praised it as a valuable step for improving content moderation on Facebook and Instagram through increased public transparency and opportunity for recourse. Meanwhile, detractors argue that it lacks the jurisdiction, legitimacy, or power to address problems relating to content moderation on Facebook and Instagram. However, because of the OB’s nascent development, there is a lack of scholarship assessing the OB’s various strengths and weaknesses in a comprehensive way; most analyses have focused on a particular aspect of the OB to praise or criticize it. This article intends to fill such a gap. In particular, the article provides a framework to evaluate the OB’s main strengths and weaknesses and how to address those weaknesses. It is structured into seven more sections. Section two outlines some essential background information on the OB, and the relevant legal environment surrounding the OB. Section three discusses three strengths of the OB. Section four discusses four weaknesses of the OB. Section five analyses a single OB decision to illustrate how some of these strengths and weaknesses become manifest in practice. Section six discusses two key relationships that pose challenges and opportunities for the OB’s future. Section seven proposes several reforms to the OB’s precedent and how such reforms could undergird the evolution of the OB in a way that could address some of its institutional weaknesses. Section eight concludes the article.

2 Background on the Oversight Board

The OB reviews content moderation decisions on Facebook and Instagram. Specifically, it can review cases where a post or content was removed from the platform to assess whether that content should have been left up, and cases where a post was left up to evaluate whether that content should have been removed from the platform. Additionally, Meta is permitted to “refer additional content types to the board for review” and “request advisory policy statements from the board” (Oversight Board Bylaws, 2022, p. 22).

2.1 Oversight Board: What it is and How it Works

The OB “is not designed to be a simple extension of (Meta’s) existing content review process” but rather to “review a selected number of highly emblematic cases and determine if decisions were made in accordance with [Meta’s] stated values and policies” (Oversight Board, n.d.). It focuses particularly on “the impact of removing content in light of human rights norms protecting free expression” balanced against other values such as “authenticity, safety, privacy and dignity” (Bickert, 2019; Oversight Board Charter, 2019).

There are two main governing documents for the OB: the Charter, which “specifies the board’s authority, scope and procedures,” and the Bylaws, which “specify the operational procedures of the board” (Oversight Board Charter, 2019). The charter will prevail over the bylaws if the two conflict. The OB has five powers over the content that it reviews. It can (1) “Request that Facebook provide information reasonably required for board deliberations in a timely and transparent manner”; (2) “Interpret Facebook’s Community Standards and other relevant policies (collectively referred to as “content policies”) in light of Facebook’s articulated values;” (3) “Instruct Facebook to allow or remove content;” (4) “Instruct Facebook to uphold or reverse a designation that led to an enforcement outcome;” and (5) “Issue prompt, written explanations of the board’s decisions” (Oversight Board Charter, 2019).

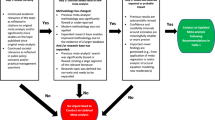

The OB first selects content moderation decisions to review, with both users and Meta permitted to submit cases for review. Once the OB selects a case, it assembles a five-member panel to review and adjudicate it, with at least one member from the relevant region presiding on the panel. It then publishes a summary of the case online so that users can submit public comments. The panel considers information contributed by the user, Meta, outside experts, and public commenters to assess whether a given post “violates Meta’s content policies, values, and human rights standards” (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, p. 10). Once the panel reaches a decision, the panel issues a draft decision to all OB members that must be approved by a majority of members, before publishing a written statement explaining its decision which can also contain policy recommendations for Meta. Once the decision is published, Meta must implement the OB’s ruling pertaining to whether to take down or leave up the content in question. Meta must also respond to the decision’s policy recommendations within sixty days (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, p. 10).

The OB can impact Facebook and Instagram’s content moderation in three ways. First, the OB issues rulings that uphold or overturn Meta’s moderation action. Meta is obligated to implement the OB’s ruling for that case unless doing so “could violate the law” in the relevant jurisdiction (Appeals Process, n.d.). Second, the OB can interpret and issue recommendations concerning Meta’s policies, procedures, and community standards. Meta is not bound to implement these recommendations, but it has committed to assess and respond to recommendations within sixty days. Finally, the OB’s past decisions can serve as precedent for future content moderation decisions that resemble the past decision in terms of the facts or issues of the case. For context, “precedent refers to a court decision that is considered as authority for deciding subsequent cases involving identical or similar facts, or similar legal issues” (Precedent, 2020). Notably, Meta determines whether precedent applies in a given case. It will assess whether “identical content with parallel context associated with the board’s decision... remains on Facebook” and will take action on that content if “it has the technical and operational capacity” to do so (Oversight Board Bylaws, 2022, p. 25). Currently, precedent can only be applied to remove content on Facebook or Instagram, but not to restore recently taken down content.

The OB is funded by an independent trust established by Meta. When the OB was launched, Meta committed $130 million to the trust to cover the OB’s budget and compensate the OB’s members for their work. It committed an additional $150 million to the trust in July 2022 (Securing Ongoing Funding for the Oversight Board, 2022).

The OB, and the concept of independent oversight boards for social media platforms, represent a form of platform self-governance, which can be understood as self-regulation in the digital space (Douek, 2019a, pp. 1–6). Self-regulation occurs when the “‘regulator’ issues commands that apply to itself” (Cusumano et al., 2021). Platform self-regulation represents social media platforms’ response to the “horizontal” model of rights, whereby nongovernmental actors are expected to preserve and protect basic human rights, and the development and implementation of laws such as Germany’s Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) that create legal obligations for platforms when moderating content.Footnote 1 Platform self-regulation also implicitly acknowledges the potential risks that can arise when states regulate speech extensively. The OB differs from traditional self-regulation mechanisms because it is semi-independent (the OB is legally independent from Meta) whereas, as Cusumano et al. note, many self-regulatory mechanisms are managed by the regulatory target themselves.

2.2 Interaction of the OB with Current Law

The most relevant government law pertaining specifically to independent bodies reviewing platform moderation decisions is the Digital Services Act (DSA), a law to “create a safer digital space” that protects “the fundamental rights of all users.” The European Parliament and EU member states reached an agreement on the DSA on April 23, 2022. The DSA is currently awaiting approval from the European Council of Ministers (The Digital Services Act Package, n.d.).

Articles 17 and 18 of the DSA offer interesting juxtapositions to the OB. Article 17 mandates that online platforms provide users access to an internal complaint-handling system of the platform whereby users can file complaints about content removal and visibility; suspension/termination of user accounts; suspension/termination of provision of service to the users; and suspension/termination of users’ monetization of content (Texts Adopted—Digital Services Act, 2022). Article 18 states that users are entitled to select “out-of-court dispute settlement bodies” as an alternative forum for resolving such content moderation disputes. Such dispute settlement bodies can also oversee “complaints that could not be resolved by means of the internal complaint-handling system” (Texts Adopted—Digital Services Act, 2022). Such bodies must be certified by the Digital Services Coordinator of the Member State where it is established.

Article 17 internal complaint systems differ from the OB, because the OB does not constitute an “internal” system since it is legally independent from Meta. Additionally, the OB is designed to hear far fewer cases than a traditional internal complaint system. Finally, the OB not only resolves content moderation disputes but issues policy recommendations and develops precedent from its past decisions.

The Article 18 dispute settlement bodies provide an interesting comparison point on to the OB, but still have key differences. One similarity is that both bodies are independent from social media platforms. However, there remain several key differences between the OB and Article 18 dispute settlement bodies. Whereas the OB reviews a content moderation decision to determine if it was made correctly (for example by examining the nature of the post itself, or the relevant platform policies), Article 18’s emphasis on “resolving disputes” suggests that the dispute settlement bodies may instead focus on facilitating negotiation between platforms and users to reach a given outcome. Additionally, another difference is that the OB’s decisions are binding on Meta, whereas the Article 18 dispute settlement bodies lacks the “power to impose the binding solution on the parties.” Finally, the OB was founded by Meta whereas the Article 18 dispute settlement bodies will be established by EU member states.

In terms of legal constraints on the OB’s purview, the OB’s bylaws prevent it from reviewing cases “where the underlying content is unlawful in a jurisdiction with a connection to the content (such as the jurisdiction of the posting party and/or the reporting party) and where a board decision to allow the content on the platform could lead to adverse governmental action against [Meta], [Meta] employees, the administration, or the board’s members” or “decisions made... pursuant to legal obligations” (Oversight Board Bylaws, 2022, pp. 19, 20). In such contexts, the OB’s purview is constrained by the laws of individual jurisdictions (which could entail not only nations but also sub-national entities). For example, in Thailand, the government has previously ordered Facebook to remove social media posts that the government found to violate lese majeste laws or risk facing legal action for noncompliance. Thus, the OB likely cannot take a case where the creator of the post is from Thailand because of the legal vulnerability to Meta (Thailand Gives Facebook until Tuesday to Remove “illegal” Content, 2017).

3 Three Significant Strengths of the OB

The OB has at least three significant strengths: its ability to enhance the transparency of content moderation decisions and processes, its ability to effect reform indirectly through policy recommendation, and its assertiveness in interpreting its jurisdiction and overruling Meta. We analyse each of them separately in the rest of this section.

3.1 Transparency of Content Moderation

The OB’s ability to publicise how Meta makes moderation decisions is beneficial in highlighting ambiguities or inadequacies in Meta’s rules and policies that become manifest when moderation decisions are taken. By reviewing Meta’s policies, the OB can highlight blind spots in Facebook’s and Instagram’s Community Standards and reveal “internal rule books and designations” that are not publicly available (Douek, 2021a). It can also disrupt institutional inertia that might otherwise sustain and preserve harmful policies, by formalising processes for reviewing and publicising platform policies (Douek, 2019b, pp. 55–56). Consider the following two examples.

The OB overturned the removal of a post quoting Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda for the Nazi Party in Germany (Patel & Hecht-Felella, 2021). The OB ruled that the policy cited for the removal, Meta’s policy on Dangerous Individuals and Organisations, did not satisfy international human rights requirements that “rules restricting expression” be “clear, precise and publicly accessible.” This policy permitted the removal of posts that “praise” or “support” an organisation listed by Meta as dangerous. However, it failed to define “praise” and “support”, specify organisations or individuals considered dangerous, or clarify that Meta requires users to specify that they are not praising or supporting listed individuals or organisations they quote.

The OB can also investigate broader policies, tools, or other facets of Meta, through queries made during the deliberation of cases or separate investigations. For example, the OB is reviewing the “XCheck” program at Meta’s request. This exempts some celebrities and political leaders from some content moderation rules. The OB will issue some recommendations on how it should be reformed (“Facebook Oversight Board to Review System That Exempts Elite Users,” 2021; Zakrezewski, 2021).

Through these various roles, the OB’s decisions, investigations, and findings can provide Meta with the insights to address blind spots. Such roles can also enable the public to understand and discuss platform content moderation decisions, and how platforms balance concerns of freedom of expression with other values such as safety and diversity. In doing so, this facilitates “the public reasoning necessary for persons in a pluralistic community to come to accept the rules that govern them, even if they disagree with the substance of those rules” (Douek, 2019b, p. 7).

3.2 Influential Policy Recommendations

The OB’s policy recommendations have proven influential in changing some of Meta’s policies and practices. For example, Meta has agreed to translate Facebook’s Community Standards into Punjabi, Urdu, and other major South Asian languages, which could provide up to 400 million more people with access to the Community standards in their home language, and notify users whose content was removed about the specific rule they violated. Meta also committed to assessing whether Facebook was policing content in Hebrew and Arabic fairly, and defining and clarifying key terms of the Dangerous Individuals and Organizations Policy (Olson, 2021; Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, p. 55). Improving user access to community standards and clarifying company policies will enhance users’ ability to express themselves freely while complying with platform policies.

Notably, the OB has not shied away from issuing far-reaching policy recommendations. In Case IG-7THR3SI1, which concerned the removal of an Instagram post for containing a female nipple as part of a breast cancer awareness campaign, the OB recommended that Meta notify users when automation has been used to moderate their content and conduct an internal audit to assess the accuracy of its automated moderation systems. In that same case, the OB also highlighted the ambiguous relationship between Facebook’s Community Standards and Instagram’s Community Guidelines, recommending that the OB clarify that Facebook’s Community Standards would take precedence over Instagram’s Community Standards if the two conflict (Case Decision IG-7THR3SI1, 2021). Meta is implementing these specific recommendations either partly or fully (Transparency Centre, 2022).

Some critics have argued that the nonbinding nature of the OB’s policy recommendations should be considered a weakness. For example, Amélie Heldt warns of the limits of “unenforceable practical guidance” to compel the behaviour of platforms, arguing that “only when regulation stipulates ‘sticks’—that is, financial disadvantages such as the high fines under NetzDG—will the provisions be implemented” (Heldt, 2019, pp. 363–364). However, the nonbinding nature of the OB’s policy recommendations may be appropriate for the OB at this time. Douek argues that nonbinding policy recommendations may be better than binding policy recommendations to resolve difficult “competing rights claims” surrounding free expression that underlie content moderation decisions; increase the likelihood that Meta agrees to broaden the OB’s jurisdiction in the long run; reduce the degree of reputational harm to the OB if Meta consistently ignores the policy recommendations; and enable Meta to respond more flexibly to the demands of online speech (Douek, 2019b, p. 7). Moreover, nonbinding policy recommendations shift the burden of responsibility to Meta to make the final decision on whether to implement proposed policy changes rather than simply abdicating responsibility for drafting rules and policies to the OB. Finally, it is worth noting that Meta has voluntarily committed to implementing many of the policy recommendations despite their non-binding nature.

3.3 Assertiveness

The OB’s previously mentioned strengths mean little if the OB is unwilling to wield its oversight and review powers against Meta, or if it merely affirms Meta’s original decisions. However, another notable strength of the OB is its assertiveness, manifested in its willingness to overrule Meta. Looking at existing cases as of September 22, 2022, out of the OB’s 27 decisions issued in 2021, the OB overturned Meta’s content moderation decision in 20 cases (74 per cent of cases) and upheld Meta’s decision in 7 cases (26 per cent). For example, in September 2022, the OB overturned the removal of a Facebook post that consisted of a cartoon depicting police violence in Colombia (Case Decision FB-I964KKM6, 2022). While statistics do not ensure the OB’s independence or the quality of the rulings themselves, the fact that the OB has overruled Meta’s decision most of the time so far suggests it is not simply affirming Meta’s content moderation decisions (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, p. 6).

The OB has also exercised its authority in interpreting its jurisdiction in unexpectedly important ways. In Case Decision IG-7THR3SI1 (the same case discussed in Sect. 3.2), the OB clarified that Meta could not remove a given OB case from the OB review simply by reversing its original moderation decision. In doing so, the OB rejected Meta’s argument that the reversal of the initial moderation decision eliminated the disagreement between the user posting the content and Facebook. Interpreting the Oversight Board Charter, the OB clarified that the “need for disagreement applies only at the moment the user exhausts [Meta’s] internal appeal process” but not after, noting that Meta’s interpretation would allow Meta to “exclude cases from OB review” simply by reversing its content moderation decision to agree with the user (Case Decision IG-7THR3SI1, 2021). In doing so, the OB exercised its authority to interpret and clarify its jurisdiction while implicitly establishing its right to interpret the Charter in general (Douek, 2021a).

4 Four Weaknesses of the OB

Despite its strengths, the OB also has four significant weaknesses: its limited jurisdiction, limited impact, Meta’s control over the OB’s precedent, and its lack of diversity. In this case too, let us analyse them individually.

4.1 Limited Jurisdiction

Although the previous section noted the OB’s assertiveness in interpreting ambiguities in the Charter, the OB’s interpretations cannot overrule the explicit limits of its jurisdiction. Because the OB can only rule to affirm or overrule Meta’s original content moderation decision, it is restricted to a “binary approach” to content moderation, which prevents it from developing and implementing alternative content moderation remedies or responses that may be appropriate for more complicated or ambiguous cases (Goldman, 2021, p. 5).

Furthermore, the OB can only rule on content moderation decisions about individual posts but not accounts (whether personal accounts, or pages for public figures, businesses, or other topics) or groups, although the OB is currently “in dialogue with Meta on expanding the Board’s scope” to review user appeals against Meta’s decisions regarding Facebook groups and accounts (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, p. 67). The limits on the OB’s jurisdiction inhibits its ability to confront the array of questions relating to freedom of expression that emerge with a platform’s moderation of content, which applies not only to how platforms moderate posts but also how they moderate individual accounts and online groups.

4.2 Limited Impact

The OB’s limited jurisdiction circumscribes its impact, which can be understood in terms of established institutional power and the number of cases considered by the OB. In terms of institutional power, the Board’s decision in a given case only governs that specific case, and its policy recommendations are not binding. As Douek argues, Meta’s retention of final authority makes it difficult for the OB to claim credibly that Meta is bound by the OB’s decisions (Douek, 2019b). Theoretically, Meta could disobey the OB’s decisions, ignore the policy recommendations without publicly responding to them, or simply choose not to provide future funding to the OB (there has been no indication that Meta intends to do any of the preceding activities). The OB cannot rule on, or mandate changes to, broader platform features such as Facebook’s recommendation algorithms, advertising systems, or data collection, restricting its ability to confront more systemic issues; only Meta can decide whether changes to such features should be made (Ghosh, 2019; Oversight Board Charter, 2019). As Douek writes, “The [OB’s] legitimacy as a true check on [Meta] requires that it be meaningfully empowered to review the main content moderation decisions (Facebook and Instagram) makes—not only a small subset of them that are peripheral to (Meta’s) main product” (Douek, 2020).

The OB’s limited impact is also indicated by the limited number of cases it decides, which reflects an approach of “quality over quantity” that does not provide equal opportunity for every user to have their case reviewed by the OB (Schultz, 2021, p. 156). In 2021, the OB issued a total of 20 decisions out of 130 shortlisted cases and approximately over 1 million cases submitted to the OB (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, pp. 6, 21). Its small caseload means it will likely miss chances to improve critical areas of content moderation, resulting in a “lost opportunity to provide all users with an internal access-to-justice mechanism” and to shed light on important freedom of expression challenges (Schultz, 2021, p. 157).

4.3 Meta’s Control Over the OB’s Precedent

The configuration of the OB’s precedent also undermines its effectiveness for the OB. As discussed earlier, Meta has committed to applying past OB decisions to “identical content in parallel context” where doing so is “technically and operationally feasible” (Oversight Board Charter, 2019). The OB’s precedent is an interesting yet understudied means by which the OB can have a lasting impact. For example, the OB could rely on precedents to decide cases and thereby increase the overall number of cases it reviews; enhance public understanding of Facebook and Instagram’s content moderation rules through accumulating a body of rulings that interpret platform policies; and enhance the consistency of content moderation decisions, thereby bolstering public trust in the platforms. We shall return to this point in Sect. 7, discussing how the OB could be improved. Here, it will suffice to note that the two standards that govern the OB’s precedent—“identical content in parallel context” and “technically and operationally feasible”—risk being overly strict and subjective. According to Frederick Schauer, “for a decision to be precedent for another decision does not require that the facts of the earlier and the later cases be absolutely identical”, because otherwise, under such a requirement, “nothing would be a precedent for anything else” (Schauer, 1987, p. 577). Using these criteria, Meta—who interprets them—could effectively nullify the use of any precedent by citing trivial differences between two cases or by overestimating the difficulty of applying precedent to a current case. This “unduly fine-grained approach” could make the OB’s “decisions impossible to implement at scale” and limit the long-term impact that the OB could have through precedent (Douek, 2021b). Without information from Meta on how frequently it has applied OB precedents or how it interprets the guidelines for applying precedent, the concern is whether Meta has interpreted such criteria overly narrowly.

4.4 Lack of Diversity

A final weakness of the OB is the lack of diversity among its 23 members, who select and rule on the cases, and the users’ appeals to the OB concerning potential cases. Although over half of the OB’s decisions in 2021 pertained to countries in the Global South and the OB currently exhibits gender parity, by other diversity measurements, the Board continues to fall short in ways that could hinder its effectiveness in confronting and clarifying challenges of freedom of expression, particularly for historically underrepresented regions or populations.

Consider geographic diversity. Most of the OB’s members are from the USA and Europe, even though many severe challenges regarding content moderation are in Global South regions, such as Africa and Asia. Jenny Domino, writing in 2020, criticised the OB for having only one out of 20 members (5 per cent) from Southeast Asia. This underrepresentation is problematic considering that, as of 2019, Southeast Asia contained four of the top 10 countries with the largest Facebook audiences in 2019 (Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore), while the USA and Canada, which represent the largest bloc of members on the OB, had the lowest number of monthly and daily active Facebook users during that period (Domino, 2020). Looking specifically at the OB’s co-chairs, two are from the USA, with no co-chair from Africa or Asia. Given that the OB co-chairs determine its administration through hiring staff and board members, selecting cases, and establishing institutional priorities and standards, ensuring sufficient diversity throughout the OB’s hierarchy is crucial to the OB’s effectiveness. Note that there are also no representatives from indigenous communities, who may have unique concerns relating to content moderation if their community has experienced or continues to experience marginalisation (Pallero & Tackett, 2020, p. 6).

The lack of diversity among the OB’s co-chairs and members could become self-perpetuating. Members may be inclined to nominate and select individuals for future membership on the OB who resemble and think like them. The lack of diversity among the OB’s members could lead the OB to prioritise freedom of expression over other human rights, especially privacy and safety, in jurisdictions where that prioritisation could endanger minority groups often subjected to hate speech. Rebecca Hamilton argues that content moderation is predominantly understood through the perspective of “mainstream Western communities”, which presumes that the State regulates rather than abuses social media and that rule of law exists. Such presumptions may not accurately reflect the experiences of users from the Global South or from marginalised communities in Western societies, where regimes may utilise their governance or regulatory power to restrict online expression and persecute or harass political dissenters (Hamilton, 2021).

The OB’s membership also reflects a lack of diversity in non-geographical aspects, such as LGBTQ or disabled communities, which may be impacted by content moderation in ways for which geographic conceptions of diversity may not sufficiently account (Pallero & Tackett, 2020, p. 6).

Lack of diversity is manifest not only in the OB’s membership but also in the users’ appeals to the OB. In 2021, more than two-thirds of user appeals came from the Global North (U.S., Canada, and Europe), with significant geographic regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Central and South Asia representing just 2 per cent of appeals. This may reflect Global South users’ lack of awareness of, or access to, the OB, making it more difficult for them to appeal to the OB to review cases directly affecting them (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022). The lack of diversity among users submitting appeals could result in insufficient attention from the OB to Global South countries where Meta’s policies have endangered local citizens’ safety or free expression (Parmar, 2020). As Leo Hochberg argues, Meta’s “existing systems and content moderation policies have given Syria’s government a digital upper hand over opposition groups.” For example, Facebook’s algorithms have frequently removed posts documenting human rights abuses, making it difficult to preserve such evidence for future accountability efforts or prosecution (Hochberg, 2021). Meanwhile, its narrow definitions of hate speech, which do not include “conflict affiliation” and “profession” among protected characteristics for moderating hate speech, have resulted in posts dehumanising members of the political opposition remaining on the platform (Hochberg, 2021).

5 Case Analysis

To illustrate what we have argued in the previous two sections regarding the OB’s strengths and weaknesses, we now analyse a specific case, OB Case FB-MP4ZC4CC, which concerned the removal of a Facebook post uploaded from Ethiopia concerning the country’s ongoing ethnic conflict. This case has not been analysed extensively in the academic literature, unlike other cases, such as the ban of former US President Trump. However, it has at least three features that make it worthwhile to analyse. First, it focuses on a country in the Global South. Second, it has unique implications as an example of platform content moderation in an active conflict zone, highlighting unique tensions between the right to free expression and the importance of reporting updated information versus the potential incitement or exacerbation of violence. Thus, it may be particularly pertinent for other ongoing conflicts, such as the current Russia-Ukraine war. Finally, the OB’s reliance on Facebook’s Violence and Incitement Community Standard rather than the Hate Speech Community Standard could have significant implications for how Meta and the OB approach similar cases in the future.

5.1 The Case Background

In July 2021, a Facebook user located in Ethiopia posted in Amharic (the “‘working language” of Ethiopia’s federal government and one of the most widely spoken languages in the country), accusing the Tigray People’s Liberation FrontFootnote 2 and ethnic Tigrayan civilians of committing “atrocities in Ethiopia’s Amhara region” including the killing, rape, and looting of civilians in the region (Case Decision FB-MP4ZC4CC, 2021; Crummey et al., n.d.). The post’s author claimed to have received this information from residents of a town in Amhara that had been attacked by Tigrayan forces. The post concluded by stating that “we will ensure our freedom through our struggle” (Case Decision FB-MP4ZC4CC, 2021). Meta’s automatic Amharic language systems flagged the post, and a content moderator removed the post for violating Facebook’s Hate Speech Community Standard. For reference, Facebook defines hate speech as a direct attack against people... on the basis of protected characteristics,” with a direct attack including (but not limited to) “violent or dehumani[s]ing speech, harmful stereotypes, [and] statements of inferiority,” and protected characteristics as including (but not limited to) race, ethnicity, nationality, religious affiliation, sexuality, gender and caste (Hate Speech, 2022).

The user appealed this removal to Meta, which upheld the original moderation decision. The user then submitted an appeal to the OB. After the OB selected the case for review, Meta determined that its initial decision to remove the post was incorrect because it did not target the Tigray ethnic group, and the user’s allegations did not resemble hate speech. Consequently, Meta restored the post.

The OB ultimately upheld Meta’s original decision to remove the post but determined that the post violated Facebook’s Community Standard on Violence and Incitement instead. This standard prohibits “misinformation and unverifiable rumours that contribute to the risk of imminent violence or physical harm.” The OB found that the post in question contained an unverifiable rumour, since the author failed to provide circumstantial evidence to substantiate his allegations, and Meta could not verify the post’s allegations, and because the allegations would likely heighten the “risk of imminent violence” (Case Decision FB-MP4ZC4CC, 2021). The OB also found that Meta’s human rights responsibilities supported the removal of the post, since the circulation of unverifiable rumours during an active conflict could exacerbate intergroup tensions and violence. The OB acknowledged the balance between preserving freedom of expression and reducing the threat of conflict, since accurate reporting of atrocities could save lives while inaccurate reporting could exacerbate the risk of further violence. Because Meta had restored the post after initially removing it, the OB’s decision required Meta to remove the post again.

In addition to its findings, the OB recommended that Meta:

-

1)

modify its value of “Safety” to acknowledge the threat that online speech could pose to the physical security of individuals;

-

2)

modify its Community Standards to acknowledge the heightened risk of unverified rumours to persons’ rights of life and security (to then be reflected throughout different levels of the moderation process);

-

3)

and commission an independent, human rights due diligence assessment to analyse how Facebook and Instagram have been used in Ethiopia to disseminate hate speech and unverified rumours in ways that exacerbate the risk of violence.

Meta decided to implement recommendation (1) only partly. It decided not to take further action on recommendation (2) because of the importance of timely reporting of violence in high-risk areas and the distinction between “unverified” rumours, which are not verified but could be verified in time, and unverifiable rumours, which cannot be confirmed or disproved in a reasonable timeframe, and the potential harms of removing information that is not currently verified. Regarding recommendation (3), Meta committed to assessing its feasibility, emphasising the challenges of conducting such analysis in a conflict zone (Oversight Board Selects a Case Regarding a Post Discussing the Situation in Ethiopia, 2022).

5.2 Reliance on Community Standard on Violence and Incitement to Overrule Meta

One interesting element of this case was the OB’s reliance on Meta’s Community Standard on Violence and Incitement and not the Hate Speech Community Standard, which Meta initially cited when removing the post. Potential reasons for reliance on the Violence and Incitement Community Standard could be the difficulty of discerning what constitutes hate speech, particularly for moderators who may lack relevant cultural knowledge, the controversial or polarising nature of moderating hate speech, and different interpretations of hate speech. For example, Aswad and David Kaye note how “U.N. and regional standards converge and conflict with regard to hate speech” (Aswad & Kaye, 2022, p. 171).

In this case, the two Meta moderators who oversaw the initial removal and consequent appeal of the post were from Meta’s Amharic content moderation team, but it is unclear whether the OB members who presided over the case had sufficient knowledge of local norms or laws to discern whether the post constituted hate speech in that jurisdiction. By comparison, determining whether a post is intended to incite violence may be easier for moderators to discern. Given the challenge of interpreting hate speech, this OB ruling could result in future moderation decisions focusing on incitement of violence rather than hate speech, especially in conflict zones.

Finally, this ruling showed one of the OB’s strengths discussed above: its willingness to overrule Meta’s final content moderation decision while also proposing alternative policies for Meta to rely upon for certain content moderation decisions.

5.3 Importance and Pitfalls of Verifiability Standard

Given the possibility of greater reliance on the Violence and Incitement Community Standard in the future, another notable element of this ruling is the importance and limitation of verifiability as a standard for governing content moderation decisions in which a threat of violence could be imminent. Considering the importance of verifiability, a crucial question is whether the OB would have ruled differently if the post incited or encouraged violence but included circumstantial evidence or appeared to be verifiable. The OB’s ruling and emphasis on verifiability suggest that the OB would be inclined to rule in favour of leaving such a post up.

Understanding the limits of the verifiability standard is crucial, given that the verifiability standard may become more critical for content moderation. The number of OB cases related to Facebook’s rules on violence and incitement rose from “9% in Q4 [the fourth quarter of] 2020 to 29% in Q4 2021,” while cases on hate speech fell from “47% in Q4 2020 to just 25% in Q4 2021,” (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, p. 19). It is worth noting that a verifiable or true post that encourages violence against another group remains dangerous; its basis on true or verifiable information does not nullify the post’s harm, and may even increase its circulation. Such a post could still be removed for violating other community standards that do not rely on verifiability, such as the Hate Speech Community Standard, but that may not always occur. While the verifiability of a post should remain relevant for a Community Standard on Inciting Violence, that specific Community Standard would benefit from clarification on the importance of verifiability compared to other considerations when determining whether a post has violated the Community Standard. For example, in some cases, it could be beneficial to remove a post that relies on verifiable information but poses a severe risk of violence to incite significant violence.

The importance of the verifiability standard in this OB decision – which reflects the salience of the verifiability standard in many debates on content moderation – reflects the OB’s ability to raise awareness of critical questions and debate in content moderation for Meta to confront, which is a strength. However, the fact that the OB cannot compel further action from Meta on these issues is a weakness.

6 Main Challenges and Opportunities for the OB Moving Forward

The previous analysis of the OB’s main strengths and weaknesses helps contextualise the OB’s future development. However, the analysis would be incomplete without discussing OB’s future relationship with Meta and governments. Such relationships will likely pose new challenges and opportunities for the OB’s future and will be crucial in determining how it evolves.

6.1 The OB’s relationship with Meta

The OB’s development over time will shape its scope and independence from Meta. However, while we stressed the OB’s limited jurisdiction, recent scholarship suggests that the OB’s current Charter and Bylaws could be interpreted in a way that enables the OB to access information about key features of Meta, such as platform algorithms. Edward Pickup argues that the existing Charter authorises the OB to “access Facebook’s algorithms as part of its standard review process and to make recommendations regarding algorithms’ impact on Facebook” (Pickup, 2021, p. 4). He points to the Charter’s provisions that “for cases under review, Facebook will provide information, in compliance with applicable legal and privacy restrictions, that is reasonably required for the board to make a decision” and the OB’s bylaws that allow it to request information regarding “engagement and reach of the content” and “information regarding Facebook’s decision and policies” (Oversight Board Charter, 2019; Oversight Board Bylaws, 2022, p. 24). Consequently, he argues that “access to algorithms is ‘reasonably required’” for the OB’s decision-making because algorithms “determine the reach of content,” which is essential for understanding the impact of speech on Facebook’s community values – a critical consideration for the OB’s decision-making (Pickup, 2021, p. 10). Gaining access to such information could provide several benefits, such as revealing insights relevant to the OB’s decisions and policy recommendations, while enhancing public knowledge about Facebook’s algorithms.

A crucial consideration moving forward concerns the OB’s jurisdiction over the Metaverse, which is a convergence of the “physical and digital worlds” where “digital representations of people” can interact within “interlinked worlds” (Milmo, 2021). The Metaverse is Meta’s primary focus and may remain so for the foreseeable future. Experts have raised various concerns about the Metaverse, ranging from racism and sexual harassment to potential disinformation and surveillance (Bokinni, 2022; Jackson, 2022). Given the nascent development of the Metaverse, it is crucial to develop rules and standards for governing it and designate actors responsible for interpreting and implementing such rules [reference anonymised]. Considering the risks of government and corporate actors abusing such responsibility for their self-interest, the OB may be appropriate for overseeing the Metaverse.

As discussed earlier, the OB is assessing its role regarding Meta’s “content moderation plans” for the Metaverse (Oversight Board Annual Report, 2021, 2022, p. 67). It is unclear whether the OB has, or will have, jurisdiction over the Metaverse. As of August 2022, the OB’s stated purpose is “to promote free expression by making principled, independent decisions regarding content on Facebook and Instagram and by issuing recommendations on the relevant Facebook Company Content Policy” (Oversight Board, n.d.). Based on that wording, if the Metaverse is a completely or largely separate product from Instagram or Facebook, then the OB likely lacks jurisdiction over the Metaverse, unless Meta expands the OB’s jurisdiction accordingly. Regrettably, a lack of jurisdiction over the Metaverse could reduce the OB’s relevance, especially if the Metaverse remains Meta’s emphasis moving forward. However, if the Metaverse is primarily integrated within existing platforms such as Facebook or Instagram, it could be argued that the OB should have jurisdiction in the Metaverse.

If the OB did have jurisdiction over the Metaverse, at least three pressing questions would arise. First, whether the OB would continue its current approach of focusing on a limited number of cases around the most significant issues or questions or seek to review a larger number of cases to oversee more disputes. Second, whether the OB would simply maintain its current role of overturning or upholding Meta’s content moderation decisions, or deploy other content moderation “remedies” beyond that binary (Goldman, 2021, p. 5). And third, whether the OB would limit its focus to content moderation or oversee and review other issues such as advertising, disinformation, mental health, surveillance, or harassment that may be particularly salient in the Metaverse.

6.2 Relationship with governments

Given the uncertainty of the OB’s relationship with Meta and whether it will have jurisdiction over the Metaverse, cooperation between the OB and governments could amplify the OB’s effectiveness as a platform governance institution. For example, laws such as the DSA could compel social media platforms to implement specific processes of content moderation, guarantee basic protections for users, or even require platforms whose user base exceeds a particular size to establish institutions like the OB. They could also establish guidelines for determining how virtual-reality environments like the Metaverse are regulated, whether by internal mechanisms, external and independent dispute-resolution bodies, or judicial courts. In doing so, governments can “[legitimize] the processes by which platforms make decisions about speech” (Douek, 2019a, p. 7).

Government-mandated processes or features of content moderation reflect Douek’s model of “‘verified accountability,’ where platforms must make aspects of their governance transparent and accountable, while governments regulate to verify these commitments” (Douek, 2019a, p. 8). Verification could occur through “regulatory audits of platforms’ dispute resolution systems” by “administrative agencies” (Van Loo, 2021, p. 888). Government-mandated individual protections in the digital realm reflect Eric Langvardt’s proposal of “the government... oversee[ing] private content moderators to ensure that they observe some legally defined set of speech rights” (Langvardt, 2018, p. 1363), and Rory Van Loo’s proposal of “platform federal rules” intended to mirror the Federal Rules of the US legal system. Van Loo’s platform federal rules include principles such as “equal access” to mechanisms of platform justice (i.e. navigable, affordable, easily comprehensible and impartial processes); standing for non-users (who can be affected by platform actions); timeliness and transparency of resolution; user class actions in cases when users experience systemic harms due to another user or the platform; guidelines governing injunctions and bans of user accounts (Van Loo, 2021, pp. 875–881).

Provisions of the DSA already reflect these concerns. Article 17 requires that providers “ensure that their internal complaint-handling systems are easy to access, user-friendly and enable and facilitate the submission of sufficiently precise and adequately substantiated complaints” and “ensure that their internal complaint-handling systems are easy to access, user-friendly and enable and facilitate the submission of sufficiently precise and adequately substantiated complaints.” Article 18 requires that dispute settlement bodies are impartial and independent of the disputing parties and possess the necessary expertise for settling the dispute (Texts Adopted—Digital Services Act, 2022). The ongoing development of the OB could provide useful insights for laws around digital platforms. For example, one area upon which the OB could shed light is whether Article 18 of the DSA should be amended so that dispute settlement bodies bind the parties with their decision. A second area could be whether Article 18 bodies should be able to develop and rely on precedent. More generally, the process of establishing the OB from the ground up could provide useful guidance for how EU Member States can create effective bodies for settling such disputes, since the DSA does not provide significant guidance as to how such institutions should be structured. Some key logistical questions may include how to select members for these bodies and for how long.

At the same time, the OB could be subject to coercion from governments. In recent years, “states are increasingly coercing online platforms and intermediaries to instantiate and enforce public policy preferences regarding online speech and privacy through private regulation... that lacks critical accountability mechanisms” (Bloch-Wehba, 2019, p. 30). It remains unclear whether the OB would challenge governmental laws, policies, and demands that restrict expression, since the OB currently cannot review cases where the content in question is illegal in a jurisdiction that is connected to the content and where a board decision could result in “adverse governmental action” against Meta, Meta employees, Meta administrators administration, or the OB and its members (Oversight Board Bylaws, 2022, pp. 19, 20).

Relying on international human rights law (IHRL) to challenge illegitimate orders or requests made by nation-states could preserve the OB’s power to protect fundamental rights and liberties, such as freedom of expression. The OB already cites IHRL, specifically the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which “establish a voluntary framework for the human rights responsibilities of private businesses,” to critique Facebook’s policies (Case Decision FB-2RDRCAVQ, 2021).

In recent Board decisions, IHRL and Meta’s human rights responsibilities have superseded Meta’s policies (Gradoni, 2021). In FB-6YHRXHZR, a supporter of opposition leader Alexei Navalny (“Navalny Supporter”) commented calling another user (“Protest Critic”) a “cowardly bot” in response to Protest Critic commenting that pro-Navalny protesters were “school children” who were “slow” and “shamelessly used.” Meta removed Navalny Supporter’s comment for violating the Bullying and Harassment Community Standard. However, the OB reversed the decision because it was “an unnecessary and disproportionate restriction on free expression under international human rights standards” (Case Decision FB-6YHRXHZR, 2021). If the OB relies on IHRL to critique Meta’s policies, it could also use IHRL to denounce government laws that infringe on human rights.

Ultimately, the OB must negotiate its relationship with governments carefully, balancing the opportunities that governments may offer for enhancing the OB’s effectiveness or purview as a platform governance institution while protecting itself from potential negative interference from governments.

7 Four recommendations to improve the OB

In this section, we make four commendations for improving the OB. Three are centred around reforming the nature of the OB’s precedent. Specifically, we recommend authorising the OB to determine when precedent applies, applying precedent to existing content moderation disputes rather than all content on Facebook and Instagram, and clarifying the meaning of the main criteria for applying precedent. A fourth recommendation concerns expanding the OB to include appellate boards staffed by users to determine whether OB precedent can be applied to existing content moderation cases, and to explore how the structure of the OB could be modified and expanded to address some of its institutional weaknesses.

These recommendations are not meant to be exhaustive. We decided to focus on the OB’s precedent because it is a remarkable low-hanging fruit. Although its uncertain nature is a severe weakness, if reformed effectively, it could offer a simple yet powerful opportunity to improve the OB’s efficiency, consistency, and accessibility. The repeated use of past OB rulings to determine similar or identical cases of content moderation could help clarify the nuances and ambiguities of Facebook’s and Instagram’s content policies and community standards, illustrate the importance of the OB’s decisions, and improve the consistency of content moderation decisions across the two platforms, while facilitating the extension of the OB’s jurisdiction over the Metaverse. Unfortunately, as mentioned in Sect. 4.3, the OB’s precedential power is significantly undercut by Meta’s decisive role in determining when past decisions are applied to current content moderation decisions (by interpreting the criteria for applying precedent), and the ambiguity of the precedential power’s criteria. Such weaknesses should be addressed. Let us now look at the four recommendations in detail.

7.1 Authorising the OB to Decide When to Invoke Precedent

The OB should be authorised to decide when to invoke precedent, to increase its control and independence from Meta in determining when its precedent is invoked. Given that Meta is directly involved in the content moderation disputes reviewed by the OB, it is peculiar to allow Meta to potentially influence how that dispute may be resolved via the invocation of precedent. Instead, the OB should be free to calibrate its own “extent of reliance on precedent” based on the current circumstances of online expression, by deciding which decisions should be used as precedent and when and how they serve as precedent (Schauer, 1987, p. 604).

7.2 Applying OB Precedent to Currently Appealed Decisions

OB’s precedents should be applied to decisions about content moderation that are currently appealed, rather than to all content currently on Facebook or Instagram. This would streamline the process of determining whether to invoke precedent in a given case, making it easier to invoke precedent (or assess whether it should be invoked) so more frequently. It would also help remove the current bias towards removing content from the platform, since the OB applies precedent only to content currently on Facebook and Instagram and not to content recently removed from the platforms. If combined with provisions for enhancing records-keeping, information access and transparency about individual submitted OB cases, this would enable a more complex and nuanced understanding of OB precedents that can evolve in line with changing circumstances and that could be observed and studied by other actors. It would also make it easier to determine historically which OB precedents have been the most important in shaping content moderation decisions, providing a means by which the OB could assess and learn from its own rulings to improve its decision-making over time.

7.3 Clarifying the Criteria for Precedent

The conditions necessary to satisfy the two criteria of applying the OB’s precedent (“identical content with parallel context” and “technical and operational feasibility”), should be clarified in detail. Given the improbability of two content moderation cases being completely identical in content and the opacity of determining the feasibility of applying a past decision, greater clarity on what those standards mean and what circumstances are necessary to satisfy those standards would improve understanding of the OB’s precedent and the degree to which any given content moderation case can serve as precedent.

7.4 Expanding the OB to Create an Appellate System

Even if the reforms to the OB’s precedent were implemented, other weaknesses of the Oversight Board remain unaddressed, especially its limited jurisdiction, limited impact, and lack of diversity, as well as a lack of opportunity for everyday users to participate. This last recommendation is intended to expand the OB in a way that addresses these other weaknesses. Specifically, under this reform, the OB’s existing infrastructure would be extended to create a more extensive system of multiple review boards, with the OB sitting as the highest board, with final decision-making authority. Below the existing Oversight Board, which for the remainder of this section we shall call “the Supreme Oversight Board” (SOB), would sit review boards akin to appellate courts, which we shall call “appellate boards”. For clarity, for the remainder of this section, “OB” will refer to the overall institution consisting of the SOB and the appellate boards.

The appellate boards would be staffed by everyday users temporarily appointed to those boards. Rather than ruling on whether to overturn or uphold Meta’s content moderation decisions, the appointed users would only be responsible for determining whether previous OB decisions should serve as precedents for deciding ongoing content moderation cases. For example, users could determine whether the facts between two cases were sufficiently similar to support the application of precedent. If no existing OB rulings applied to a given moderation case, then the original moderation decision for that case would apply unless the SOB elected to review the case itself. The SOB would be permitted to review and potentially overturn the appellate board’s decision if it felt that it had applied or interpreted the precedent incorrectly.

In terms of recruitment for such appellate boards, users could be recruited to serve on the appellate boards through random selection from a pool of all users in the relevant geographic region of a given case, and participants could receive a small financial reward.

This reform would expand the OB’s potential impact and enhance its efficiency by enabling it to rule on more cases. Moreover, it would offer an increased opportunity for user participation compared to the status quo, in which Facebook and Instagram users can only participate by submitting cases for OB appeal and providing public comments on cases selected for review, and thereby lack “direct accountability mechanisms” or “a fair opportunity to participate” (Klonick, 2020, p. 2490, 2018, p. 1603). Allowing opportunities for public participation via appellate boards could increase public trust in the OB, since the OB could incorporate and better represent the views of everyday users whose viewpoints and norms may differ in critical ways from that of Board Members. This reform also facilitates greater fluidity in how the OB utilises precedent at a given time, allowing it to calibrate to the demands of users.

To address the OB’s issues relating to diversity, such appellate boards could focus on specific jurisdictions and be populated with users from that jurisdiction. Doing so would partly address the OB’s overrepresentation of Western-born board members and underrepresentation of Global South cases and populations. The scale of the jurisdiction for selecting appellate board members could be adjusted based on what is most feasible for a given geographic location. The fact that users would only be appointed to appellate boards for a limited number of cases and would only be responsible for determining whether a particular rule should apply would address a common dilemma of participatory governance of enabling participation among everyday users while ensuring that participation is not unduly burdensome. Applying precedents from past cases to ongoing cases would improve Meta’s broader policymaking process by determining through experimentation what principles from past cases should be integrated into existing policies and revealing crucial aspects of how their implementation should be defined or managed, providing an opportunity to make content moderation more consistent.

Critics may object that the OB, if so expanded, could overshadow Article 18 dispute settlement bodies or other similar government institutions established in the future to adjudicate content moderation disputes. In doing so, the OB could pre-empt government-supported bodies. Indeed, there is a risk that the OB could nullify their effectiveness. However, the OB could also provide crucial insights into how to improve the implementation of Article 18 dispute settlement bodies or other similar bodies in the future. Additionally, the OB and DSA Article 18 dispute settlement bodies may differ slightly in their remit, as the DSA is focused primarily on illegal content whereas the OB may be most impactful for content that is not illegal, strictly speaking, but potentially harmful regardless.

8 Conclusion

It is difficult to classify the OB as a success or failure at this stage. The OB is not meant to solve all of Facebook’s and Instagram’s issues. Even within its limited jurisdiction, its impact remains limited, and it lacks control over its precedent. It also remains insufficiently diverse. However, it still possesses a significant potential to improve content moderation on Facebook and Instagram, by demystifying and clarifying content moderation decisions and processes, proposing meaningful reforms through policy recommendations, and being willing to reverse Meta’s content moderation decision and interpret its own jurisdiction. Therefore, it is much better than nothing, but it could be much more. Addressing the OB’s weaknesses, specifically, the nature of its precedent, could provide a pathway to strengthen and expand the OB in a way that realises its potential and makes it a valuable complement to robust, international legislation.

Notes

NetzDG (Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz, or the “Network Enforcement Act”) is a German law that requires social media networks with at least 2 million registered users in Germany to remove “clearly illegal” content within 24 h after a user complaint, investigate the content’s legality within 7 days, or face a fine of up to 50 million euros for noncompliance (Gesley, 2021).

Tigray is a region located in Northern Ethiopia. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front was previously a military organization that “dominated Ethiopian politics for nearly three decades,” and it is currently at war with the Ethiopian federal government (Walsh & Dahir, 2022).

References

Appeals process. (n.d.). Oversight Board. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://oversightboard.com/appeals-process/. Accessed 22 Oct 2022

Aswad, E., & Kaye, D. (2022). Convergence & conflict: reflections on global and regional human rights standards on hate speech. Northwestern Journal of Human Rights, 20(3), 165–216.

Bickert, M. (2019). Updating the values that inform our community standards. Meta.

Bloch-Wehba, H. (2019). Global Platform Governance: Private Power in the Shadow of the State. SMU Law Review, 72(9), 27–80.

Bokinni, Y. (2022). A barrage of assault, racism and rape jokes: My nightmare trip into the metaverse. The Guardian.

Case decision FB-MP4ZC4CC. (2021). Oversight Board. https://oversightboard.com/decision/FB-MP4ZC4CC/

Case decision FB-6YHRXHZR. (2021). Oversight Board. https://www.oversightboard.com/decision/FB-6YHRXHZR

Case decision FB-2RDRCAVQ. (2021). Oversight Board. https://oversightboard.com/decision/FB-2RDRCAVQ/

Case decision FB-I964KKM6. (2022). Oversight Board. https://www.oversightboard.com/decision/FB-I964KKM6/

Transparency Centre. (2022). Meta. https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/oversight/oversight-board-recommendations/

Crummey, D. E., Marcus, H. G., & Mehretu, A. (n.d.). Ethiopia. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Ethiopia. Accessed 22 Oct 2022

Cusumano, M. A., Gawer, A., & Yoffie, D. B. (2021). Can self-regulation save digital platforms? Industrial and Corporate Change, 30, 1259–1285.

Case Decision IG-7THR3SI1. (2021). Oversight Board. https://www.oversightboard.com/decision/IG-7THR3SI1/

Domino, J. (2020). Why Facebook’s Oversight Board is Not Diverse Enough. Just Security.

Douek, E. (2019a). Verified Accountability: Self-Regulation of Content Moderation As an Answer to the Special Problems of Speech Regulation (No. 1903; Aegis Series, pp. 1–28). Hoover Institution. London. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/douek_verified_accountability_aegisnstl1903_webreadypdf.pdf

Douek, E. (2020). What kind of oversight board have you given us? University of Chicago Law Review Online, 1. https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/uchidial88§ion=36&casa_token=KvzlSTNn4RoAAAAA:CyXsTtT4ci5dE9NHueROgAXtTeDaW4uZlkQFPmE89cs76-hR4y4SUxSOJySIQ5bmwPys8g2g

Douek, E. (2019b). Facebook’s “Oversight Board:” Move fast with stable infrastructure and humility. North Carolina Journal of Law and Technology, 21(1), 1–78.

Douek, E. (2021a). The facebook oversight board’s first decisions: Ambitious, and perhaps impractical. Lawfare.

Douek, E. (2021b). The oversight board moment you should’ve been waiting for: Facebook responds to the first set of decisions. Lawfare.

Facebook oversight board to review system that exempts elite users. (2021). The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/sep/21/facebook-xcheck-system-oversight-board-review

Gesley, J. (2021). Germany: Network Enforcement Act Amended to Better Fight Online Hate Speech. Library of Congress.

Ghosh, D. (2019, October 16). Facebook’s Oversight Board Is Not Enough. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/10/facebooks-oversight-board-is-not-enough

Goldman, E. (2021). Content moderation remedies. Michigan Technology Law Review, 28, 1–59.

Gradoni, L. (2021). How platform governance had its Marbury v Madison. Verfassungsblog.

Hamilton, R. (2021). De-platforming following capitol insurrection highlights global inequities behind content moderation. Just Security.

Heldt, A. (2019). Let’s meet halfway: Sharing new responsibilities in a digital age. Journal of Information Policy, 9, 336–369.

Hochberg, L. (2021). How Facebook’s Oversight Board Can Do More for Syria. Middle East Institute.

Jackson, L. (2022). Is the Metaverse Just Marketing? New York Times.

Klonick, K. (2018). The new governors: The people, rules, and processes governing online speech. Harvard Law Review, 131, 1598–1670.

Klonick, K. (2020). The facebook oversight board: creating an independent institution to adjudicate online free expression. Yale Law Journal, 129, 2418–2499.

Langvardt, K. (2018). Regulating Online Content Moderation. The Georgetown Law Journal, 106, 1353–1388.

Milmo, D. (2021). Enter the metaverse: the digital future Mark Zuckerberg is steering us toward. The Guardian.

Olson, P. (2021). Don’t Dismiss Facebook’s Oversight Board. It’s Making Some Progress. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-10-25/facebook-s-oversight-board-is-the-only-lever-to-reform-the-social-media-behemoth

Oversight Board Charter. (2019). Oversight Board. https://www.oversightboard.com/governance/

Oversight Board Annual Report 2021. (2022). Oversight Board.

Oversight Board Bylaws. (2022). Oversight Board. https://www.oversightboard.com/sr/governance/bylaws

Oversight Board Selects a Case Regarding a Post Discussing the Situation in Ethiopia. (2022). Meta. https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/oversight/oversight-board-cases/raya-kobo-ethiopia/

Oversight Board. (n.d.). Oversight Board. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://oversightboard.com/

Pallero, J., & Tackett, C. (2020). What the Facebook Oversight Board Means for Human Rights, and Where We Go From Here. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/cms/assets/uploads/2020/06/Response-to-FB-Oversight-Board-announcement.pdf

Parmar, S. (2020). Facebook’s oversight board: A meaningful turn toward international human rights standards? Just Security.

Patel, F., & Hecht-Felella, L. (2021). Oversight Board’s First Rulings Show Facebook’s Rules Are a Mess. Just Security.

Pickup, E. L. (2021). The Oversight Board’s Dormant Power to Review Facebook’s Algorithms. Yale Journal on Regulation, 39, 1–22.

Precedent. (2020). Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/precedent

Schauer, F. (1987). Precedent. Stanford Law Review, 39(3), 571–605.

Schultz, M. (2021). Six Problems with Facebook’s Oversight Board. Not enough contract law, too much human rights. In J. Bayer, B. Holznagel, P. Korpisaari, & L. Woods (Eds.), Perspectives on Platform Regulation (pp. 145–164). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co KG.

Securing ongoing funding for the Oversight Board. (2022). Oversight Board. https://oversightboard.com/news/1111826643064185-securing-ongoing-funding-for-the-oversight-board/

Hate Speech. (2022). Meta. https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/

Texts adopted—Digital Services Act, (2022). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0269_EN.html

Thailand gives Facebook until Tuesday to remove “illegal” content. (2017). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-facebook/thailand-gives-facebook-until-tuesday-to-remove-illegal-content-idUSKBN188168

The Digital Services Act package. (n.d.). European Commission. Retrieved September 22, 2022, from https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package#:~:text=The%20Digital%20Services%20Act%20and,level%20playing%20field%20for%20businesses

Van Loo, R. (2021). Federal Rules of Platform Procedure. University of Chicago Law Review, 88(4), 829–896.

Walsh, D., & Dahir, A. L. (2022). Why Is Ethiopia at War With Itself? London: New York Times.

Zakrezewski, C. (2021). Facebook Oversight Board sternly criticizes the company’s collaboration in first transparency reports. London: The Washington Post.

Funding

DW was funded by a Shirley Scholarship, Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, D., Floridi, L. Meta’s Oversight Board: A Review and Critical Assessment. Minds & Machines 33, 261–284 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-022-09613-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-022-09613-x