Abstract

Primary care plays a central role in the provision of health care, and is an organizing feature for health care delivery systems in most Western industrialized democracies. For a variety of reasons, however, the practice of primary care has been in decline in the U.S. This paper reviews key primary care concepts and their definitions, notes the increasingly complex interplay between primary care and the broader health care system, and offers research priorities to support future measurement, delivery and understanding of the role of primary care features on health care costs and quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Increased attention is being directed toward ascertaining how to maximize the efficiency and quality of health care in the U.S.1 Part of this effort involves bolstering the primary care infrastructure2,3 which plays a central role in health care provision and is an organizing feature of health care delivery systems in most Western industrialized democracies.4–6 Systems (both within the U.S. and internationally) that emphasize the primary care role have lower per capita costs, better health outcomes and lower rates of premature mortality for a range of conditions.7–19 However, for a variety of reasons, the practice of primary care has been in decline in the U.S.20–22

Accordingly, a number of policy initiatives are underway to re-invigorate the area of primary care. These may be complicated, however, by diverse perspectives on what constitutes primary care and the evolving delivery system in which the primary care functions occur. To further efforts in grappling with this complexity, we discuss the definitions of primary care, its increasingly complex interplay with the broader health care system, and potential future data needs and research to evaluate the impacts of primary care features on health care costs and quality.

WHAT IS PRIMARY CARE?

Efforts to define the features of primary care began in the 1960s with the formal recognition of the continuing importance of the generalist physician in the face of increasing medical sub-specialization and related care fragmentation.4–6,23 As part of this effort, U.S. policymakers assumed that primary care and its workforce could be defined by the numbers of practicing physicians with generalist training (e.g., family medicine physicians, general internists, pediatricians and, in past decades, “general practitioners”), but changing roles now challenge this assumption.24,25 Not all physicians trained as generalists practice primary care; many work as hospitalists and in urgent care or free-standing emergency departments,26–28 on specialized care teams, and in consultative medicine.29,30 Nurse practitioners and physicians assistants also contribute to primary care delivery, but many work instead in specialty care settings.31

From these earliest definitional efforts, primary care has been recognized as having five elements which, when present, collectively differentiate it from specialty-oriented health care: first-contact accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, coordination, and accountability for the whole person.4,5,32–34 Table 1 provides an updated definition of each primary care element, derived from prior work.4,5,32–34

Taken individually, no one feature is unique to primary care. For example, retail clinics35 provide convenient access, but do not necessarily provide comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic expertise or the skills and capabilities for chronic illness management or care coordination. Critical care physicians provide comprehensive care during life-threatening illnesses, and must coordinate with multiple clinicians, but their practice does not typically allow for personal relationships beyond the acute episode. Some medical specialists provide continuity for their patients with active disease (e.g., oncologists caring for patients in the phase of active cancer treatment) as well as coordination with other key professionals (e.g., surgeons).36 However their, practice does not usually provide comprehensive and accessible care across all of a patient’s health care needs over time.37–39 To fulfill the primary care role for such patients, clinician practices must fulfill all five primary care features.4–6

Patient safety and patient-centeredness are additional commonly referenced attributes40 which, while important to primary care, are not unique to it. Patients rightfully expect clinicians, regardless of specialty, to provide clinically competent, professional, safe and patient-centered care.40

Primary Care Features and Associations with Patient Outcomes

Over the past 40 years since these five primary care features were first articulated, health services researchers have explored ways to measure them and their association with patient outcomes and costs. Whole-person accountability has been largely measured by surveys; the other four features have been measured via patient and provider surveys or by administrative data such as claims. Some randomized controlled trials have included one or more primary care features, but identifying the role of any single feature on outcomes is challenging given the multifaceted nature of those interventions.

Accessibility involves several aspects, including financial access (e.g., affordability of services and types of insurance accepted by the practice), cultural access (e.g., languages spoken), organizational access (e.g., ease of getting an appointment and after-hours care), and geographic access (e.g., location near population served, ease of transport to the practice location).4 Better organizational accessibility has been consistently associated with fewer emergency room visits41,42 and lower rates of hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions.43,44 Likewise, access to after-hours care coordinated with the primary care provider is associated with lower rates of hospitalization and emergency department use, greater patient satisfaction and fewer unmet medical needs.45–48

Continuity also has various components, including informational continuity (the availability of a patient’s health information at the point of care), continuity with the same practice over time, and interpersonal continuity with the same clinician over time.4,5,49,50 These last two aspects are the concepts most often referenced in primary care research; they have been associated with lower hospitalization rates,51–56 lower complication rates for patients with chronic conditions,55 fewer emergency room visits,57,58 lower total costs53 and lower episode-based costs for chronic conditions.54,55,59,60 Greater site and interpersonal continuity are also associated with increased use of preventive services and guideline-concordant care.61–68 Interpersonal continuity is highly valued by both patients and providers, and it has been associated with better adherence to provider recommendations.69–71

Comprehensive primary care, which involves meeting the large majority of each patient’s physical and mental health care needs, has been associated with better health outcomes provided at lower cost,11,14,17,23,72,73 lower hospitalization rates for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions,14,74 improved health and better self-reported health outcomes,11,14,17,72,75 and greater equity (i.e., reduced disparities in disease severity as a result of earlier detection and prevention across different populations).11,14,17,23

Better coordination between primary care and specialists (reflected by better communication and information exchange, use of nurses to help coordinate patient care between providers, or primary care coordination of referrals to specialists) has been associated with less service duplication, better patient outcomes,76–78 greater satisfaction for providers and patients,78,79 and higher overall efficiency.79–81 Formal care coordination interventions for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions have had mixed effects on service use and expenditures.74,82,83 The greatest benefits have been realized in patients at moderate to severe risk or who receive care in multiple locations, and when there is substantial contact between the patient and the care coordinator co-located with the patient’s usual physician.84,85

Elements of accountable whole-person care, including clinician knowledge of a person’s overall medical history, preferences, and family and cultural orientation, have been associated with improved patient self-management for chronic conditions,4,5,86 adherence to physicians’ advice, and self-reported health status improvements.87 Greater whole-patient centered communication has also been associated with better patient recovery from discomfort, fewer patient concerns, and fewer diagnostic tests and referrals.88

Studying Primary Care Features in a Complex Health Care System

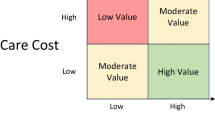

These studies highlight the definitional intricacies and potential value of each primary care feature. While conceptually each feature should be fully present for a practice to be delivering optimal primary care, in reality, there are inherent tradeoffs and complementarities among them. Some elements may require more emphasis than others, depending on patient preferences and needs. A commonly noted tradeoff occurs between accessibility and continuity; it is impossible for a single clinician with a continuous ongoing relationship with a patient to be accessible 24/7. Thus patients needing immediate access for sick care, including some healthy young adults, may be willing to forego some interpersonal continuity.89–92 Patients also have differing constellations of acute and chronic conditions, functional limitations, expectations, and family and community resources—all of which affect the amount of care coordination required and the complexity of delivering comprehensive care to them by the practice team.93 Nonetheless, while patients may prioritize different elements of primary care at different times in their lives, they will likely benefit from all five elements for much of their lifespan.4,5,17 And while young working-age (e.g., 40–60 years) persons may place different levels of emphasis on continuity with a primary care clinician, it is precisely this age group that benefits from early identification and secondary prevention for common asymptomatic conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia and type II diabetes by a clinician who knows them well,4 potentially avoiding future morbidity and higher costs (compared to patients for whom these conditions go undetected and unmanaged).

Changes in health care since the 1960s when the five primary care features were first described have imposed research challenges regarding appropriate ways to measure the presence and use of new tools, the growing expectations of practice capabilities (e.g., population health management), the need for more interprofessional primary care teamwork, and changes in practice ownership models. Even since Starfield’s conceptualization of the structure and processes underlying each element,4 new tools (e.g., electronic health records, secure electronic messaging, electronic referrals and clinical decision support) and knowledge of care processes (e.g., risk-stratified care management and chronic condition management) have been developed with the potential to support each primary care feature. In both small and large practices, care may now be delivered not just by an office-based generalist, but also by an interprofessional primary care team, which is typically a lead clinician and other key personnel such as nurses and medical assistants (MAs). One of these may take on the role of care manager, or there may be a different dedicated professional (e.g., social worker, advanced practice nurse) working with the team to engage resources external to the practice (e.g., community-based social supports, behavioral health professionals, pharmacists). The goals of primary care teamwork include offloading nonclinical tasks from physicians, making more efficient use of all available professionals, and enhancing the comprehensiveness and coordination of care.22,93 The primary care team may serve home-bound patients and collaborate through “virtual” practice locations.94 Ownership arrangements are also more complex, ranging from more traditional physician-owned practices, which may or may not be part of provider networks, to practices fully owned by health or hospital systems.95

These changes in primary care delivery need to be considered when assessing the five defining features and their relationship to patient outcomes. Figure 1 illustrates the context in which primary care may be provided for patients. As depicted, the patient and the primary care team are influenced by available resources and infrastructure at their practice site, by the larger practice organization of which the practice may be a part, the affiliated provider networks of specialists and hospitals,96 and local market- and community-level factors and resources.97–99

In this complex environment, there are a variety of structures and care processes4,100,101 to support the primary care elements. For example, robust health information technology (HIT) can enhance patient access via secure electronic messaging through a patient Web portal, coordination with specialists or facilities, and informational continuity.102 Other primary care innovations like pre-visit planning and primary care team “huddles”103 may facilitate information continuity, comprehensiveness and coordination of care.

Furthermore, the defining elements of primary care, while conceptually distinct, can complement one another. Starfield noted that continuity of care was a structural prerequisite to coordination; without it, there is no accountable provider to coordinate care.4 Not surprisingly, continuity of care has been positively associated with enhanced coordination.4,104,105 In addition, more comprehensive care can enhance patient continuity and facilitate coordination of care, with reduced care fragmentation.4,14

Support for each of the defining primary care elements can come from different levels of a larger health system. For example, support for HIT adoption and implementation, data feedback, support for patient self-management,86 and practice facilitators106 could come from within a primary care practice or from the larger physician organization or hospital/health system affiliation. Patient-centered medical home (PCMH) initiatives,107,108 which strive to bolster primary care through increased reimbursement and the creation of guideposts for practice capabilities,109 include varying support for these tools.93,110,111

The conceptual framework also notes the potential role of health plans and payer policies. PCMH initiatives,107,108,112 for example, may lead to a better understanding of the measurement, support and use of alternative payment models for primary care. Others have noted, however, that the complex nature and heterogeneity of the PCMH design makes it difficult not only to compare across demonstration programs, but also to discern which elements of practice change contributed to patient outcomes.113,114 For example, comprehensiveness is not a formal element of national organizations’ PCMH recognition and accreditation programs,109,115–117 and the degree of implementation of other core features of primary care (e.g., accessibility, continuity) can vary dramatically among practices that achieve top marks on medical home recognition tools (see paper entitled “Measuring Comprehensiveness of Primary Care” in this same supplementary issue of JGIM). As reflected in this conceptual framework, a PCMH intervention might have positive, negative or no effects on patient outcomes,118–120 depending in part on whether it truly captures the essential features of primary care. Thus there is an ongoing need to examine the individual, relative and combined contributions of the five defining elements of primary care in relation to patient outcomes.

Priorities for Future Data and Research

To better understand and support the processes involved in primary care, it would be useful to have measures and data sources that capture the various aspects of the five primary care elements and their relationship to the quality and cost of health care. Table 2 presents a list of illustrative key variables and the types of data sources that could provide information on elements of the conceptual framework in order to examine associations between primary care features and patient outcomes. Depending on the research question of interest, some would serve as key independent variables, others as controlling variables, and others as dependent variables.

A particular challenge is measuring the extent to which each primary care feature is present and realized by practices and patients. Measures of accessibility are complicated by incomplete data; for example, non-visit access via patient portals, email and phone contacts are usually not billable, and are thus not part of claims data. In addition, patients without access to health care are not typically represented in analyses of claims data or facility-based patient and provider surveys. Comprehensiveness invokes its own complex measurement issues, since it involves both the scope of services provided (e.g., immunizations, family planning, home visits) and the breadth and depth of acute and chronic conditions and problems managed by the primary care practice (see companion piece JGIM entitled "Measuring Comprehensiveness of Primary Care"). To date, most measures of comprehensiveness have focused on the scope of services provided in the practice and have paid less attention to the depth and breadth of conditions managed (e.g., multiple chronic conditions within the same patient). Coordination in primary care is also becoming more complex as patients are living with more comorbid conditions and receiving care from an increasing number of specialists and community-based services requiring intra-specialty coordination.121,122 Increasingly, coordination also includes ways that the interprofessional primary care team within the practice work together to integrate care for patients.123,124 Such teamwork has been found to be more efficient than fragmented care involving multiple specialists without a coordinated care effort.4,5,123,124 Whole-person accountability, is another primary care feature which is challenging to capture with one type of data source alone. The existence of competing or alternative approaches to each of these elements suggests opportunities to confirm efficient and valid metrics for future policy relevant research.

Table 3 lists types of data sources potentially relevant to the five primary care elements. Several existing patient, provider and facility surveys provide measures of some aspects of accessibility and continuity, as well as the clinician communication aspect of whole-person care.125–131

In addition to the revision and validation of measures of the core primary care elements, further examination of their relative contribution to patient outcomes may be helpful. As previously noted, tradeoffs are inherent with respect to areas of focus among primary care features. A practice cannot provide both maximum accessibility and interpersonal continuity to all patients. Similarly, a single clinician cannot possess the knowledge and skills to provide complete comprehensive care for every patient from newborn to frail elder. A small primary care team can be quite helpful for improving efficiency in primary care,132 but if the team becomes too large, efficient care coordination and interpersonal continuity can be compromised. Comprehensive primary care requires not only a well-trained clinician capable of managing the breadth and depth of patient problems, but also the motivation, teamwork and infrastructure to support such care.

A variety of policy-relevant research questions could be examined, for example: Which subgroups of patients benefit more from highly accessible care? Which benefit most from interpersonal continuity? Which clinician competencies are most relevant for delivering comprehensive care for particular patient subgroups? Under what circumstances do patients of clinicians who provide more comprehensive care have better health outcomes and lower costs in both the short and long term? What other aspects of the practice environment and delivery system augment these primary care features? What alternative payment models effectively promote enhanced primary care, and for which patient populations and practice settings? What is the prevalence of boutique (concierge, retainer) practices, and what impact do they have on access for the larger population that cannot afford to attend such practices?

In examining the relationships between the five primary care elements and patient outcomes, research and policy communities also need better primary and secondary data sources covering many of the data elements noted in Tables 2 and 3. Many prior studies have relied on secondary data, such a national surveys designed for other purposes, and thus they do not go into sufficient detail on the primary care capabilities of practices with regard to each of the five elements. Primary data collected expressly for this purpose both from patient125–127 and clinician surveys130–133 and as part of future EHR data,134 and that also reflect care processes and patients’ clinical needs, will likely be needed to appropriately address some of these research questions.

When secondary sources are used to observe local market variation, there is also a need for data on factors such as provider consolidation within markets and primary care/specialist supply in geographic units smaller than the county level. Such local market factors can affect physician behavior, for example, in decisions to remain in independent practice or to join a larger health system, which in turn have implications for supply-driven service utilization and cost.135–137

Data must also be collected, exchanged and aggregated across practices and settings in a usable format for analysis by the research community and for internal practice quality improvement (e.g., via practice-based research networks, health information exchanges, and data aggregators).134 In terms of data collection, there is little available information in current electronic health records on patient symptoms and reasons for the visit in the patient’s own words. Since much of primary care involves dealing with patient symptoms not yet assigned a diagnosis,4 better capture of this data in the EHR would be useful for improving our understanding and tracking of patient needs and ways to structure primary care to support those needs. In addition, aggregation of EHR data across practices could enable more efficient hypothesis testing and comparative effectiveness research in order to improve patient care, especially in combination with real-time analytics.138 The hope is that, eventually, de-identified EHR data will become a source of clinical data not currently available from either surveys or claims. However, much work remains to ensure that information is consistently collected in a useful format for analysis.139 For example, improving the accuracy of the problem list in EHRs is a clinically important research area,140 with implications for examining comprehensiveness of care as well as controlling for patient mix in analysis of outcomes.

Better aggregated data across providers could also help us understand how primary care practices that exemplify the five primary care features affect care delivered by specialists. For example, a primary care practice that provides more comprehensive care might make more appropriate referrals to specialists, thereby helping specialists use their time more efficiently. Similarly, a practice that coordinates care well may be in a better position to communicate effectively with specialists about patients for whom they share care.

Finally, in any effort to increase our knowledge of ways to improve primary care delivery, “the devil is in the details.” There is an enormous amount of work that still needs to be done in order to achieve a better understanding of how primary care teams adapt to local circumstances and adjust workflow to meet patient needs. Additional work is also needed to understand how external resources like practice facilitators and shared practice support can help practices ensure that they are robustly providing the five defining elements of primary care. To this end, qualitative work can inform our understanding of and support for improved design of structures and care processes for primary care. Data from clinician and patient surveys linked to claims and electronic health record data can proceed alongside qualitative studies to identify ways of delivering the features of primary care that are cognizant of local culture141 and population needs, and that also improve patient outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Understanding how to maximize each of the five defining features of primary care to meet patient health needs is an evolving science that must be continuously updated given the rapid pace of change in health care markets and policies. There are gaps in the use of evidence to support the implementation of changes to provide better support for primary care given the diverse financial and stakeholder efforts. Improving available data has the potential to advance the efforts to better understand and bolster the support and care processes to move each primary care element from a conceptual notion to one that is realized and that improves patient health.

References

Shipman SA, Sinsky CA. Expanding primary care capacity by reducing waste and improving the efficiency of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1990–7.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 111th Congress of the United States. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hr1enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr1enr.pdf. 2010; Accessed March 13, 2015.

Grumbach K, Grundy P. Outcomes of Implementing Patient Centered Medical Home Interventions: a Review of the Evidence from Prospective Evaluation Studies in the United States. Washington DC: Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative; 2010.

Starfield B. Primary care: balancing health needs, services and technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. In: Donaldson, M S et al., eds. Committee on the Future of Primary Care Services. ISBN 0-309-05399-4. National Academy of Sciences;1996.

World Health Organization. Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978.

Shi L. The relationship between primary care and life chances. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1992;3:321–35.

Shi L. Primary care, specialty care, and life chances. Int J Health Serv. 1994;24:431–58.

Shi L, Starfield B, Kennedy B, Kawachi I. Income inequality, primary care, and health indicators. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:275–84.

Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, Politzer R, Xu J. Primary care, race, and mortality in US states. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:65–75.

Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502.

Franks P, Fiscella K. Primary care physicians and specialists as personal physicians. Health care expenditures and mortality experience. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:105–9.

Parchman ML, Culler S. Primary care physicians and avoidable hospitalizations. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:123–8.

Kringos DS, Boerma WGW, van der Zee J, Groenewegen PP. The contribution of primary care to health care system performance in Europe. In: Kringos DS, ed. The Strength of Primary Care in Europe. Utrecht: Nivel; 2012.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:288–98.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–87.

Phillips RL Jr, Bazemore AW. Primary care and why it matters for U.S. health system reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:806–10.

Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37:111–26.

Starfield B, Shi L. The medical home, access to care, and insurance: a review of evidence. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1493–8.

Berenson RA, Rich EC. US approaches to physician payment: the deconstruction of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:613–8.

Sandy LG, Bodenheimer T, Pawlson LG, Starfield B. The political economy of U.S. primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:1136–45.

Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:799–805.

White KL. Primary medical care for families–organization and evaluation. N Engl J Med. 1967;277:847–52.

Simon CJ, White WD, Gamliel S, Kletke PR. The provision of primary care: does managed care make a difference? Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16:89–98.

Schwartz MD. The US, primary care workforce and graduate medical education policy. JAMA. 2012;308:2252–3.

Ratelle JT, Dupras DM, Alguire P, Masters P, Weissman A, West CP. Hospitalist career decisions among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1026–30.

Pham HH, Grossman JM, Cohen G, Bodenheimer T. Hospitalists and care transitions: the divorce of inpatient and outpatient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:1315–27.

Williams M, Pfeffer M. Freestanding Emergency Departments: Do they have a role in California? July 2009. California Healthcare Foundation. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/F/PDF%20FreestandingEmergencyDepartmentsIB.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Executive health. Available at: http://periopmedicine.org/2006/06/internal-medicine-preoperative.html. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Available at: http://www.emoryhealthcare.org/executive-health/staff.html. Accessed March 13, 2015.

National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Projecting the Supply of Non-Primary Care Specialty and Subspecialty Clinicians: 2010–2025. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/usworkforce/clinicalspecialties/clinicalspecialties.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Alpert J, Charney E. The Education of Physicians for Primary Care. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1973.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. “About the Patient Centered Medical Home Item Set.” Rockville MD: AHRQ, Document #1314, September 1, 2011. https://cahps.ahrq.gov/surveys-guidance/item-sets/PCMH/index.html. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Lake T, Marincic J, Stone Valenzano C, et al. Feasibility of collecting data on physicians and their practices: environmental scan report. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research; 2012.

Bohmer R. The rise of in-store clinics--threat or opportunity? N Engl J Med. 2007;356:765–768. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2437.

Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM, Chan L, Schneeweiss R. The generalist role of specialty physicians: is there a hidden system of primary care? JAMA. 1998;279:1364–70.

Casalino LP, Rittenhouse DR, Gillies RR, Shortell SM. Specialist physician practices as patient-centered medical homes. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1555–8.

Edwards ST, Mafi JN, Landon BE. Trends and quality of care in outpatient visits to generalist and specialist physicians delivering primary care in the United States, 1997–2010. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:947–55.

Fryer GE Jr, Consoli R, Miyoshi TJ, Dovey SM, Phillips RL Jr, Green LA. Specialist physicians providing primary care services in Colorado. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:81–90.

Davis K, Schoenbaum S, Audet A. A 2020 vision of patient centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:953–7.

Hochheiser LI, Woodward K, Charney E. Effect of the neighborhood health center on the use of pediatric emergency departments in Rochester, New York. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:148–52.

Shea S, Misra D, Ehrlich MH, Field L, Francis CK. Predisposing factors for severe, uncontrolled hypertension in an inner-city minority population. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:776–81.

Bindman AB, Chattopadhyay A, Osmond DH, Huen W, Bacchetti P. The impact of Medicaid managed care on hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:19–38.

Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, Komaromy M, Vranizan K, Lurie N, Billings J, Stewart A. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274:305–11.

O’Malley AS. After-hours access to primary care practices linked with lower emergency department use and less unmet medical need. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:175–83.

Jerant A, Bertakis KD, Fenton JJ, Franks P. Extended office hours and health care expenditures: a national study. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:388–95.

Grol R, Giesen P, van Uden C. After-hours care in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and the Netherlands: new models. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25:1733–7.

Zickafoose JS, DeCamp LR, Prosser LA. Association between enhanced access services in pediatric primary care and utilization of emergency departments: a national parent survey. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1389–95.e1-6.

Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327:1219–21. Review.

Saultz JW. Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1:134–43.

Mainous AG 3rd, Gill JM. The importance of continuity of care in the likelihood of future hospitalization: is site of care equivalent to a primary clinician? Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1539–41.

Christakis DA, Feudtner C, Pihoker C, Connell FA. Continuity and quality of care for children with diabetes who are covered by Medicaid. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1:99–103.

Cabana MD, Jee SH. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J Fam Pract. 2004;53:974–80.

Weiss LJ, Blustein J. Faithful patients: the effect of long-term physician-patient relationships on the costs and use of health care by older Americans. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1742–7.

Hussey PS, Schneider EC, Rudin RS, Fox S, Lai J, Pollack CE. Continuity and the Costs of Care for Chronic Disease. JAMA Internal Med. 2014;245.

Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, Strawderman RL, Weeks WB, Casalino LP, Fisher ES. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1879–85.

Rosenblatt RA, Wright GE, Baldwin LM, Chan L, Clitherow P, Chen FM, Hart LG. The effect of the doctor-patient relationship on emergency department use among the elderly. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:97–102.

Gill JM, Mainous AG 3rd, Nsereko M. The effect of continuity of care on emergency department use. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:333–8.

Raddish M, Horn SD, Sharkey PD. Continuity of care: is it cost effective? Am J Manag Care. 1999;5:727–34.

De Maeseneer JM, De Prins L, Gosset C, Heyerick J. Provider continuity in family medicine: does it make a difference for total health care costs? Ann Fam Med. 2003;1:144–8.

Ettner SL. The relationship between continuity of care and the health behaviors of patients: does having a usual physician make a difference? Med Care. 1999;37:547–55.

Regan J, Schempf AH, Yoon J, Politzer RM. The role of federally funded health centers in serving the rural population. J Rural Health. 2003;19:117–124. discussion 115–6.

Shi L, Starfield B. Primary care, income inequality, and self-rated health in the United States: a mixed-level analysis. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30:541–55.

Campbell RJ, Ramirez AM, Perez K, Roetzheim RG. Cervical cancer rates and the supply of primary care physicians in Florida. Fam Med. 2003;3560–4.

Ferrante JM, Gonzalez EC, Pal N, Roetzheim RG. Effects of physician supply on early detection of breast cancer. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13:408–14.

Roetzheim RG, Pal N, van Durme DJ, Wathington D, Ferrante JM, Gonzalez EC, Krischer JP. Increasing supplies of dermatologists and family physicians are associated with earlier stage of melanoma detection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:211–8.

Flocke SA, Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ. The association of attributes of primary care with the delivery of clinical preventive services. Med Care. 1998;36:AS21–30.

Atlas SJ, Grant RW, Ferris TG, Chang Y, Barry MJ. Patient-physician connectedness and quality of primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:325–35.

Pereira AG, Pearson SD. Patient attitudes toward continuity of care. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:909–12.

Bower P, Roland M, Campbell J, Mead N. Setting standards based on patients’ views on access and continuity: secondary analysis of data from the general practice assessment survey. BMJ. 2003;326:258.

Baker R, Mainous AG 3rd, Gray DP, Love MM. Exploration of the relationship between continuity, trust in regular doctors and patient satisfaction with consultations with family doctors. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003;21:27–32.

Lee A, Kiyu A, Milman HM, Jimenez J. Improving health and building human capital through an effective primary care system. J Urban Health. 2007;84:i75–i85. Review.

Starfield B. State of the art in research on equity in health. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2006;31:11–32.

Sans-Corrales M, Pujol-Ribera E, Gené-Badia J, Pasarín-Rua MI, Iglesias-Pérez B, Casajuana-Brunet J. Family medicine attributes related to satisfaction, health and costs. Fam Pract. 2006;23:308–16.

Wilhelmsson S, Lindberg M. Prevention and health promotion and evidence-based fields of nursing - a literature review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2007;13:254–65.

Stille CJ, Jerant A, Bell D, Meltzer D, Elmore JG. Coordinating care across diseases, settings, and clinicians: a key role for the generalist in practice. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:700–8.

Parchman ML, Noël PH, Lee S. Primary care attributes, health care system hassles, and chronic illness. Med Care. 2005;43:1123–9.

Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, Doty M, Peugh J, Zapert K. On the front lines of care: primary care doctors’ office systems, experiences, and views in seven countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25:w555–71.

Forrest CB, Glade GB, Baker AE, Bocian A, von Schrader S, Starfield B. Coordination of specialty referrals and physician satisfaction with referral care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:499–506. PubMed.

Anderson R, Barbara A, Feldman S. What patients want: a content analysis of key qualities that influence patient satisfaction. J Med Pract Manag. 2007;22:255–61.

Cummins RO, Smith RW, Inui TS. Communication failure in primary care. Failure of consultants to provide follow-up information. JAMA. 1980;243:1650–2.

Chen A, Brown R, Esposito D, Schore J, Shapiro R. Report to Congress on the Evaluation of Medicare Disease Management Programs. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. February 14, 2008. (http://www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/8795.pdf) Accessed March 13, 2015.

Smith SM, Allwright S, O’Dowd T. Effectiveness of shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in chronic disease management. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007.

Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–18.

Leff B, Reider L, Frick KD, Scharfstein DO, Boyd CM, Frey K, Karm L, Boult C. Guided care and the cost of complex healthcare: a preliminary report. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:555–9.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:64–78.

Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213–20.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804.

Rubin G, Bate A, George A, Shackley P, Hall N. Preferences for access to the GP: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:743–8.

Zickafoose JS, DeCamp LR, Sambuco DJ, Prosser LA. Parents’ preferences for enhanced access to the pediatric medical home: a qualitative study. J Ambul Care Manag. 2013;36:2–12.

Turner D, Tarrant C, Windridge K, Bryan S, Boulton M, Freeman G, Baker R. Do patients value continuity of care in general practice? An investigation using stated preference discrete choice experiments. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12:132–7.

Stoddart H, Evans M, Peters TJ, Salisbury C. The provision of ‘same-day’ care in general practice: an observational study. Fam Pract. 2003;20:41–7.

Rich EC, Lipson D, Libersky J, Peikes DN, Parchman ML. Organizing care for complex patients in the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:60–2.

Independence at Home Demonstration. Available at: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/independence-at-home/. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Shortell SM, Marsteller JA, Lin M, Pearson ML, Wu SY, Mendel P, Cretin S, Rosen M. The role of perceived team effectiveness in improving chronic illness care. Med Care. 2004;42:1040–8.

Smetana GW, Landon BE, Bindman AB, Burstin H, Davis RB, Tjia J, Rich EC. A comparison of outcomes resulting from generalist vs. specialist care for a single discrete medical condition: a systematic review and methodologic critique. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:10–20.

Conrad DA. Lessons to apply to national comprehensive healthcare reform. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:S306–21.

White C, Bond AM, Reschovsky JD. High and varying prices for privately insured patients underscore hospital market power. Res Brief. 2013;1–10.

Cunningham P, Felland L, Stark L. Safety-net providers in some US communities have increasingly embraced coordinated care models. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1698–707.

Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83:691–729.

Hogg W, Rowan M, Russell G, Geneau R, Muldoon L. Framework for primary care organizations: the importance of a structural domain. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:308–13.

O’Malley AS, Grossman JM, Cohen GR, Kemper NM, Pham HH. Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:177–85.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/Huddles.aspx. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Christakis DA, Wright JA, Zimmerman FJ, Bassett AL, Connell FA. Continuity of care is associated with well-coordinated care. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3:82–86.

O’Malley AS, Cunningham PJ. Patient experiences with coordination of care: the benefit of continuity and primary care physician as referral source. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:170–7.

Taylor EF, Machta RM, Meyers DS, Genevro J, Peikes DN. Enhancing the primary care team to provide redesigned care: the roles of practice facilitators and care managers. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:80–83.

Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Available at: http://www.pcpcc.org/. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Joint Principles of the Patient Centered Medical Home. Original statement, 2007. http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/delivery_and_payment_models/pcmh/demonstrations/jointprinc_05_17.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015.

The National Committee for Quality Assurance, Patient-Centered Medical Home Recognition tool. http://www.ncqa.org/Programs/Recognition/Practices/PatientCenteredMedicalHomePCMH.aspx. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Malouin RA, Starfield B, Sepulveda MJ. Evaluating the tools used to assess the medical home. Manag Care. 2009;18:44–48.

Ginsburg PB, Maxfield M, O’Malley AS, Peikes D, Pham HH. Making Medical Homes Work: Moving from Concept to Practice. HSC Policy Analysis No. 1. December 2008. http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/1030. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Barr MS. The patient-centered medical home: aligning payment to accelerate construction. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67:492–499.

Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro JL, Parchman ML, Meyers DS. Early evaluations of the medical home: building on a promising start. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:105–116. Review.

Bitton A, Martin C, Landon BE. A nationwide survey of patient centered medical home demonstration projects. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:584–592.

The Joint Commission, Primary Care Medical Home Accreditation tool. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/accreditation/pchi.aspx. Accessed March 13, 2015.

The Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC), Medical Home Accreditation Tool. Available at: http://www.aaahc.org/en/accreditation/primary-care-medical-home/. Accessed March 13, 2015.

URAC (formerly the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission) Patient Centered Medical Home accreditation tool. Available at: https://www.urac.org/accreditation-and-measurement/accreditation-programs/all-programs/patient-centered-medical-home/. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, Fishman PA, Hsu C, Soman MP, Trescott CE, Erikson M, Larson EB. The group health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:835–843.

Rosenthal MB, Friedberg MW, Singer SJ, Eastman D, Li Z, Schneider EC. Effect of a multipayer patient-centered medical home on health care utilization and quality: the Rhode Island chronic care sustainability initiative pilot program. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1907–1913.

Friedberg MW, Schneider EC, Rosenthal MB, Volpp KG, Werner RM. Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311:815–825.

Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1130–1139.

Starfield B, Chang HY, Lemke KW, Weiner JP. Ambulatory specialist use by nonhospitalized patients in US health plans: correlates and consequences. J Ambul Care Manag. 2009;32:216–225.

Bhat VN. Institutional arrangements and efficiency of health care delivery systems. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6:215–222.

Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care–a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1064–1071.

Starfield B, Cassidy C. Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool; 1998. Available at: http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-primary-care-policy-center/pca_tools.html. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, Rogers WH, Taira DH, Lieberman N, Ware JE. The primary care assessment survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36:728–739.

Safran DG. Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey (ACES), 2004. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center Hospitals Inc.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS® Clinician & Group Surveys: Overview of the Questionnaires. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. Document No. 2350. Available at: https://cahps.ahrq.gov/Surveys-Guidance/CG/index.html. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Shortell S, Casalino L. NSPO. 2008 http://nspo.berkeley.edu/NSPOII_MGsurvey-final-pb_20060317_c.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Medical Home Implementation Quotient (MHIQ). Available at: www.transformed.com/mhiq/welcom.cfm. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Center for Studying Health System Change, Physician Survey. 2008 Health Tracking Physician Survey Methodology Report. Technical Publication No. 77. September 2009. Available at: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/1085/. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Bodenheimer T, Laing BY. The teamlet model of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:457–461.

Klabunde CN, Willis GB, McLeod CC, Dillman DA, Johnson TP, Greene SM, Brown ML. Improving the quality of surveys of physicians and medical groups: a research agenda. Eval Health Prof. 2012;35:477–506.

Hersh WR, Cimino J, Payne PRO, Embi P, Logan J. Recommendations for the Use of Operational Electronic Health Record Data in Comparative Effectiveness Research. eGEMS (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes): 2013;Vol 1: Iss. 1, Article 14. Available at: http://repository.academyhealth.org/egems/vol1/iss1/14. Accessed March 13, 2015.

Ginsburg PB, Pawlson LG. Seeking lower prices where providers are consolidated: an examination of market and policy strategies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33:1067–1075.

O’Malley AS, Bond AM, Berenson RA. Rising hospital employment of physicians: better quality, higher costs? Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2011;1–4.

Kocher R, Sahni NR. Hospitals’ race to employ physicians–the logic behind a money-losing proposition. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1790–1793.

Miriovsky BJ, Shulman LN, Abernethy AP. Importance of health information technology, electronic health records, and continuously aggregating data to comparative effectiveness research and learning health care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4243–4248.

Bayley KB, Belnap T, Savitz L, Masica AL, Shah N, Fleming NS. Challenges in using electronic health record data for CER: experience of 4 learning organizations and solutions applied. Med Care. 2013;51:S80–S86.

Wright A, Feblowitz J, Maloney FL, Henkin S, Bates DW. Use of an electronic problem list by primary care providers and specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:968–73.

Kralewski J, Dowd BE, Kaissi A, Curoe A, Rockwood T. Measuring the culture of medical group practices. Health Care Manag Rev. 2005;30:184–93.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). We are grateful to Lara Converse from Mathematica Policy Research for her assistance with some of the literature review for the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Malley, A.S., Rich, E.C., Maccarone, A. et al. Disentangling the Linkage of Primary Care Features to Patient Outcomes: A Review of Current Literature, Data Sources, and Measurement Needs. J GEN INTERN MED 30 (Suppl 3), 576–585 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3311-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3311-9