Abstract

Purpose

Due to the recently emerging shortage in medical staff during the novel corona virus pandemic, several countries have rushed their undergraduate medical students into the emergency department. The accuracy of diagnosing critical findings on X-rays by senior medical students is not well assessed. In this study, we aim to assess the knowledge and accuracy of undergraduate final-year medical students in diagnosing life-threatening emergency conditions on chest x-ray.

Method

This is a cross-sectional nationwide survey across all medical schools in Jordan. Through an electronic questionnaire, participants were sequentially shown a total of six abnormal X-rays and one normal. For each X-ray, participants were asked to choose the most likely diagnosis, and to grade the degree of self-confidence regarding the accuracy of their answer in a score from 0 (not confident) to 10 (very confident).

Results

We included a total of 530 participants. All participants answered at least six out of seven questions correctly, out of them, 139 (26.2%) participants answered all questions correctly. Pneumoperitoneum was the highest correct answer (93.8%), whereas flail chest was the least correctly answered case with only 310 (58.5%) correct answers. Regarding self-confidence for each question, 338 participants (63.8%) reported very high overall self-confidence level. Answers related to tension pneumothorax had the highest confidence level.

Conclusion

Senior Jordanian medical students showed good knowledge with high confidence levels in diagnosing life-threatening conditions on chest x-rays, supporting their incorporation in the emergency department during pandemics and confirming the reliability of information they can extract.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chest X-ray imaging in the emergency department remains trivial in determining the pathology and triaging management, especially in high-load services. A previous report showed how accurate X-ray reporting in emergency department (ED) improved management of patients triage and reduced false-negative diagnoses [1]. While recent advances in machine learning technologies showed promises in accuracy of detecting pathologies and extracting data from different imaging modalities [2, 3], several challenges in implementing these automatic systems in clinical practice still exist [4, 5].

With the emergence of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, several countries have rushed their final-year medical students into the field to compensate for the shortage in medical doctors working in the emergency department [6]. In the UK as an example, students are expected to work in the field of their competency and willingness after their graduation; however, emergency department is the place most in need to these new graduates [7]. Assessing competency of medical students in recognizing life-threatening conditions is an important consideration when deciding to implicate medical students in practice. In this study, we aim to assess the knowledge of undergraduate final-year medical students in Jordan about the X-ray findings of life-threatening emergency conditions.

Materials and methods

Design and settings

This is a cross-sectional study conducted in all medical schools in Jordan. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of Jordan and was conducted in concordance with the latest declaration of Helsinki. The survey was conducted during March and April of 2020, where a corona virus outbreak was still ongoing in Jordan. Jordan has six universities teaching medicine: three in the central region, The University of Jordan, Hashemite University, and Al-Balqa Applied University; two in the northern region, Jordan University of Science and Technology and Al-Yarmouk University; and one in the southern region, Mut’ah University. All medical schools apply 6-year teaching programs until graduation.

Participants

We recruited sixth year medical students from all medical schools in Jordan, except from Al-Balqa Applied University, as it was recently established and the first batch will graduate in 2022.

We adopted the following inclusion criteria:

-

Sixth year medical student

-

Completed radiology rotation during their training

We used batch groups on social media, where all senior medical students are registered there, to distribute an electronic questionnaire using Google forms. All participants were informed about the nature of the survey and the privacy of their data.

Variables

Each participant was asked about general demographics (i.e., age, gender, university), their GPA, and their general self-confidence about self-competency if they are sent to the emergency department. After that, a total of six abnormal and one normal X-rays were shown sequentially. For each X-ray, the participant was asked to mention the abnormality and to grade their self-confidence about the accuracy of the answer in a score from 0 (not confident) to 10 (very confident).

After reviewing the most common life-threatening X-ray cases in our emergency department at our hospital, we chose the following six diagnoses: tension pneumothorax, pneumoperitoneum, cardiac tamponade, multiple rib fractures (flail chest), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and aortic dissection, in addition to a normal X-ray. We obtained the images from our radiology department (Fig. 1). We sent the images to two radiologists, a senior radiology resident (L. M.) and a radiology specialist (N. A), who were blinded about the diagnosis, to answer and validate the images and to comment if any other major abnormality is present and may confuse the respondents about the required answer.

Upon reviewing the results, describing the exact pathology or pointing to it in an informative way was considered a correct answer, as both cases will let the respondent to correctly triage the case to the appropriate management. For example, answering the ARDS case as “acute pulmonary edema” was considered correct. Answering aortic dissection as aortic aneurysm or widened mediastinum, answering cardiac tamponade as pericardial effusion, answering flail chest as multiple rib fractures, and answering pneumoperitoneum as perforated viscus or air under diaphragm were all considered correct answers. On the other hand, answering tension pneumothorax as pneumothorax alone was not considered true, as this might delay prompt life-saving intervention required in cases of tension pneumothorax.

Finally, we calculated the total score of correct answers by adding all correct answers together to get a score out of seven. We then calculated the total self-confidence score by adding self-confidence levels for all questions and dividing the total by seven to get an average score out of ten.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS version 21.0 (Chicago, USA) in our analysis. We used mean (± standard deviation) to describe continuous variables (e.g., age). We used count (frequency) to describe other nominal variables (e.g., gender).

We used one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test to compare GPA with total score. We used chi-square test to analyze the difference between gender and university with total score and total confidence levels, followed by post hoc Z-test for proportion. We tested the reliability of our questionnaire using reliability analysis of Cronbach’s alpha. All underlying assumptions were met, unless otherwise indicated. We adopted a p value of 0.05 as the significance threshold.

Results

We included a total of 530 participants in this study, 265 (50%) were men and 265 (50%) women, with a mean age of 23.23 (± 1.41) years. The mean GPA for the participants was 3.14 (± 0.45) out of 4. The responses showed almost balanced distribution among the included universities as follows: 134 (24.3%) participants were from Hashemite university, 127 (24.0%) from The University of Jordan, 120 (22.6%) from Jordan University of Science and Technology, 83 (15.7%) from Mut’ah University, and 66 (12.5%) from Yarmouk University. The confidence questionnaire had a high reliability score with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70.

Two hundred eighty-five (53.77%) participants answered at least six out of seven questions correctly, and out of them, 139 (26.2%) participants answered all questions correctly (Fig. 2).

The total score was significantly related to the university (< 0.001), where students from The University of Jordan had the highest number of participants with full score (Table 1). The total score was not related to GPA (0.291) or gender (p = 0.123).

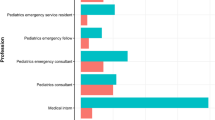

Regarding each specific question, all questions had at least 50% correct answers. Pneumoperitoneum was the highest correct answer (93.8%), whereas flail chest was the least correctly answered case with only 310 (58.5%) correct answers. Figure 3 shows the percentages of students correctly diagnosed the pathology for each case.

Regarding self-confidence for each question, 338 participants (63.8%) reported very high self-confidence level, 168 participants (31.7%) reported high confidence, and 24 (4.5%) reported moderate to low confidence level. Answers related to tension pneumothorax had the highest confidence level with 324 participants (61.1%) recorded very high confidence level, while it was the lowest for flail chest image, where only 259 participants (48.9%) recorded very high confidence (Table 2). No significant difference for GPA (p = 0.388), gender (p = 0.466), or university (p = 0.193) was found.

Discussion

Previous studies focused on assessing competency of reading chest X-rays among practicing physicians, including residents and fellows [8,9,10,11,12], and to a lesser extent medical students [13, 14]. Very few studies however have particularly focused on undergraduate medical students’ ability to identify acute life-threatening conditions [15]. Our national study found a reasonably high accuracy level among Jordanian senior medical students in identifying acute life-threatening pathologies manifesting on chest X-ray with high self-confidence scores, ranging from 58.5 to 93.8%.

A previous study compared competencies of medical students and residents in identifying critical chest X-ray findings and found a significant difference in overall scores between medical students and radiology residents, but not internal medicine residents, although residents generally had higher confidence than students [13]. Another study also did not find a significant difference in accuracy of X-ray interpretation between medical students and surgery residents [11]. In another study that assessed the ability to detect general chest X-ray findings, students and residents did not differ significantly in identifying pathologies [16]. A small study (n = 22) that was done on junior doctors to identify general pathologies on chest X-ray found a low overall accuracy and confidence (51 and 57.5%, respectively) (14). Another small study from Iran showed a low accuracy that reached only 8% for ARDS and 15% for normal chest X-ray among practitioners, pointing to the need for improving their emergency radiology curricula [9]. A recent study that included radiology residents showed that they generally have around 90.4 and 79.6% accuracy in identifying abnormal and normal chest X-rays, respectively, but only 52.7% in reaching the exact diagnosis, where they were tested on imagings of both life-threatening and non-life-threatening conditions [8].

Noteworthy, our study demonstrated significant difference in total scores between different universities which is mostly attributable to the curricula of radiology rotations taught during college years; this was also supported by a previous study that showed a significant improvement in accuracy of interpreting chest X-ray images after completing radiology rotation [15].

We believe our study has some limitations that need to be considered by future studies. The difference in total correct scores between universities points to the importance of considering a unified emergency imaging course to be implemented by all medical schools. Identifying life-threatening findings on chest X-ray is an important skill that needs to be well implemented in all radiology rotations; this is also the strategy adopted by program directors of several radiology and medical departments in the USA [17, 18]. On the other hand, we believe that our study has many strength points compared to previous similar studies as we included a representative balanced sample from medical schools all over Jordan, and we eliminated answering bias by not providing multiple choice questions, which can guide the respondent to the correct answer.

In conclusion, our national study showed high competency among senior medical students in identifying acute life-threatening findings on chest X-ray images with high self-confidence levels. The present study supports the possibility of deploying Jordanian senior medical students in emergency departments in crisis situations.

References

Hardy M, Snaith B, Scally A (2013 Jan) The impact of immediate reporting on interpretive discrepancies and patient referral pathways within the emergency department: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Radiol. 86(1021):20120112

Yu G, Gang P, Hui J, Zeng W, Yu K, Alienin O et al (2019) Deep learning with lung segmentation and bone shadow exclusion techniques for chest X-ray analysis of lung cancer. In: Hu Z, Petoukhov S, Dychka I, He M (eds) Advances in Computer Science for Engineering and Education. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 638–647 (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing)

Bhandary A, Prabhu GA, Rajinikanth V, Thanaraj KP, Satapathy SC, Robbins DE, Shasky C, Zhang YD, Tavares JMRS, Raja NSM (2020) Deep-learning framework to detect lung abnormality – a study with chest X-ray and lung CT scan images. Pattern Recognit Lett. 129:271–278

Zou L, Yu S, Meng T, Zhang Z, Liang X, Xie Y (2019) A technical review of convolutional neural network-based mammographic breast cancer diagnosis. Vol. 2019. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, Hindawi Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/cmmm/2019/6509357/

Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D (2019) Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 17(1):195

Mahase E (2020) Covid-19: medical students to be employed by NHS as part of epidemic response. BMJ. 368:m1156

Harvey A (2020) Covid-19: medical students should not work outside their competency, says BMA. BMJ. 368:m1197

Fabre C, Proisy M, Chapuis C, Jouneau S, Lentz P-A, Meunier C, Mahé G, Lederlin M (2018) Radiology residents’ skill level in chest x-ray reading. Diagn Interv Imaging. 99(6):361–370

Mehdipoor G, Salmani F, Shabestari AA (2017) Survey of practitioners’ competency for diagnosis of acute diseases manifest on chest X-ray. BMC Med Imaging. 17(1):1–6

Sethole KM, Rudman E, Hazell LJ (2020) Methods used by general practitioners to interpret chest radiographs at district hospitals in the city of Tshwane, South Africa. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci

Eid JJ, Reiley MI, Miciura AL, Macedo FI, Negussie E, Mittal VK (2019) Interpretation of basic clinical images: how are surgical residents performing compared to other trainees? J Surg Educ. 76(6):1500–1505

O’Brien KE, Cannarozzi ML, Torre DM, Mechaber AJ, Durning SJ (2008) Training and assessment of CXR/basic radiology interpretation skills: results from the 2005 CDIM Survey. Teach Learn Med. 20(2):157–162

Eisen LA, Berger JS (2006) Hegde A, Schneider RF. Competency in chest radiography. A comparison of medical students, residents, and fellows. J Gen Intern Med. 21(5):460–465

Christiansen JM, Gerke O, Karstoft J, Andersen PE (2014) Poor interpretation of chest X-rays by junior doctors. Dan Med J. 61(7):A4875

Scheiner JD, Noto RB, McCarten KM (2002) Importance of radiology clerkships in teaching medical students life-threatening abnormalities on conventional chest radiographs. Acad Radiol. 9(2):217–220

Satia I, Bashagha S, Bibi A, Ahmed R, Mellor S, Zaman F (2013) Assessing the accuracy and certainty in interpreting chest X-rays in the medical division. Clin Med. 13(4):349–352

Kondo KL, Swerdlow M (2013) Medical student radiology curriculum: what skills do residency program directors believe are essential for medical students to attain? Acad Radiol. 20(3):263–271

Schiller PT, Phillips AW, Straus CM (2018) Radiology education in medical school and residency: the views and needs of program directors. Acad Radiol. 25(10):1333–1343

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by our Institutional review Board (IRB). All participants provided written informed consent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Authorship justification

The data collection required excessive work to ensure a large representative sample size, where the authors Mo’ath Bani Ali, Areej kilani, Zain Alkhalaileh, Leen Ahmad, Ibrahim Hamad, and Yazan Alawneh performed the data collection and shared in the manuscript writing.

Development of questionnaire and assessment of their importance and relevance to ER doctors was performed by radiologists Osama Samara, Nosaiba Al-Ryalat, and Lna Malkawi, where they also participated in the manuscript drafting.

Data handling and analysis and results writing were performed by Saif Aldeen AlRyalat and Soukaina Ryalat.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samara, O., AlRyalat, S.A., Malkawi, L. et al. Assessment of final-year medical students’ performance in diagnosing critical findings on chest X-ray. Emerg Radiol 28, 333–338 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-020-01893-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-020-01893-z