Abstract

Background

Patients with dementia and multiple chronic conditions (MCC) frequently experience polypharmacy, increasing their risk of adverse drug events.

Objectives

To elucidate patient, family, and physician perspectives on medication discontinuation and recommended language for deprescribing discussions in order to inform an intervention to increase awareness of deprescribing among individuals with dementia and MCC, family caregivers and primary care physicians. We also explored participant views on culturally competent approaches to deprescribing.

Design

Qualitative approach based on semi-structured interviews with patients, caregivers, and physicians.

Participants

Patients aged ≥ 65 years with claims-based diagnosis of dementia, ≥ 1 additional chronic condition, and ≥ 5 chronic medications were recruited from an integrated delivery system in Colorado and an academic medical center in Maryland. We included caregivers when present or if patients were unable to participate due to severe cognitive impairment. Physicians were recruited within the same systems and through snowball sampling, targeting areas with large African American and Hispanic populations.

Approach

We used constant comparison to identify and compare themes between patients, caregivers, and physicians.

Key Results

We conducted interviews with 17 patients, 16 caregivers, and 16 physicians. All groups said it was important to earn trust before deprescribing, frame deprescribing as routine and positive, align deprescribing with goals of dementia care, and respect caregivers’ expertise. As in other areas of medicine, racial, ethnic, and language concordance was important to patients and caregivers from minority cultural backgrounds. Participants favored direct-to-patient educational materials, support from pharmacists and other team members, and close follow-up during deprescribing. Patients and caregivers favored language that explained deprescribing in terms of altered physiology with aging. Physicians desired communication tips addressing specific clinical situations.

Conclusions

Culturally sensitive communication within a trusted patient-physician relationship supplemented by pharmacists, and language tailored to specific clinical situations may support deprescribing in primary care for patients with dementia and MCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Most older adults with dementia have multiple chronic conditions (MCC). Guidelines for individual conditions increase polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use, in which risks of medications outweigh benefits, or medications may not align with treatment goals.1 Taking more medications is associated with adverse drug events, drug interactions, treatment burden, and negative cognitive effects.2,3,4,5 Person-centered care should incorporate medications that will help patients with dementia and MCC achieve their goals while minimizing potential harms.6

Deprescribing—reducing or stopping the use of inappropriate medications or medications unlikely to be beneficial—may improve outcomes for patients with dementia and MCC.7, 8 Effective deprescribing interventions have been multidisciplinary and many have involved the provision of direct-to-patient educational materials.9,10,11 To date, deprescribing interventions for patients with dementia have focused on specific drug classes or have been limited to inpatient or skilled nursing settings.12,13,14,15 There is a need to develop deprescribing interventions for this population that target multiple medications and can be integrated into primary care.16, 17

As yet, there is no literature on deprescribing in underrepresented minority populations. Since underrepresented minorities have a long history of disparate health care treatment, developing generalizable deprescribing interventions will require broader input. Members of minority cultural groups may benefit from approaches to deprescribing that reflect cultural and historical interactions with health care providers.18

This study was undertaken to inform the development of Optimal Medication Management in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia (OptiMize), a pragmatic, primary care–based trial to increase awareness of deprescribing among patients with dementia and MCC, family caregivers, and clinicians. Our main objective was to elicit stakeholder perspectives on the content and process of deprescribing communication in primary care. As part of this objective, and to ensure that OptiMize would be acceptable to patients from diverse communities, we also began to explore views on culturally competent approaches to deprescribing for African American and Hispanic patients.

METHODS

Design

This qualitative study was based on semi-structured interviews with patients with dementia and MCC, caregivers, and primary care physicians. The study was designed to inform the development of OptiMize, a subsequent two-part intervention to increase awareness of deprescribing among patients with dementia and MCC, caregivers, and primary care physicians. The intervention consists of an educational brochure mailed to patients and caregivers in advance of primary care visits and 12 monthly “Tip Sheets” focusing on deprescribing communication distributed to clinicians. This research was approved by the institutional review boards of Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO) and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Participants and Recruitment

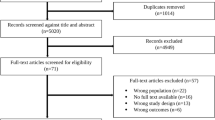

In the first phase, patients were recruited from KPCO in Denver, CO. Figure 1 lists inclusion criteria. An introductory letter was mailed to patients with “opt-out” provisions. Patients and caregivers who did not opt out were called to inquire about their interest in participating; caregivers could participate independently. In the second phase, we recruited African American patients through an academic medical center in Baltimore, MD, and Hispanic patients through KPCO.

We initially recruited physicians at KPCO through personal contacts and snowball sampling, in which participants identify potential future participants for recruitment. In the second phase of recruitment, we used personal contacts and snowball sampling to expand physician recruitment to several health systems in different states, targeting areas with large African American and Hispanic populations.

Interview Guide

The interview guides (Appendix) were developed by a multidisciplinary team that included geriatricians, pharmacists, and health services researchers. The guides were designed to elicit perspectives on medication use, deprescribing, and patient-physician communication relating to medication decisions. Participants were also asked for feedback on the educational materials designed for OptiMize. Drawing on previous health care disparities research, we adapted the question guides for members of underrepresented minority groups to additionally focus on cultural perceptions of deprescribing, trust, and physician communication.19,20,21

Data Collection and Analysis

The same multidisciplinary team that developed the interview guide (LW, KSG, CK, BS, RB, JN, CMB, EAB, and ARG) conducted interviews from March 2018 to June 2019. All interviewers were trained by the principal investigators, who regularly reviewed interview transcripts to ensure that consistent methods were used. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; interviews with Spanish-speaking patients were conducted in Spanish and translated into English for analysis. Analysis was performed using Atlas.ti, version 8 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development). The study team reviewed the transcripts in weekly meetings and continued data collection until no new ideas emerged (i.e., thematic saturation). We used constant comparison22 to identify themes and compare them between patients, caregivers, and physicians and across racial/ethnic groups. A preliminary coding scheme was iteratively refined and applied to the data. We used inductive coding, in which codes emerged from the data, and deductive coding, in which we created pre-set codes based on literature about deprescribing23, 24 and health disparities.25, 26 Each transcript was independently coded by two investigators. Differences were reconciled by consensus among all study team members until 100% agreement was reached.

RESULTS

We conducted interviews with 17 patients, 16 caregivers, and 16 physicians. Demographic information was not collected for the first 28 interviews; during the second phase of interviews, 9 participants self-identified as Black/African American and 5 as Hispanic/Latino. In total, 16 physicians from 12 clinics, 4 states, and the District of Columbia participated. Content analysis revealed 5 major themes, presented below. Table 1 presents exemplar quotations.

Theme 1: Establish Trust

Establishing trust between physicians, patients, and caregivers was seen as foundational for deprescribing. Many patients and caregivers said they would be more likely to accept a physician’s deprescribing recommendation if they already trusted the physician. For example, “I really trust [my doctor]... If she told me to get off a medication, I would.” Physicians said that having a longstanding relationship with the patient and caregiver made it easier to raise difficult issues, such as deprescribing preventive medicines due to limited life expectancy: “If you’ve been providing care for a patient [and] interacting with caregivers for a time... that extended duration with them builds trust and willingness to... deprescribe.” Not only was trust necessary before initiating deprescribing conversations, but patients and caregivers said they had lost confidence in physicians who were not open to deprescribing. As one patient said, “Every time I went to [the doctor]... it was the same thing—‘Just continue taking your medications.’ Nothing was getting better… I didn’t trust him anymore after that.”

The importance of trust was reflected in comments by participants of different races and ethnicities. As one African American patient said, “If a doctor told me to stop the medicine, I would think that he did it because he really felt that’s what’s needed to be done and it had nothing to do with race.” Similarly, a Hispanic patient said, “I stop a medication if the doctor tells me to do so because he is the only one that knows.” However, some key nuances emerged around the issues of trust and communication, particularly for Spanish-speaking patients. Though patients from all racial and ethnic groups cited time pressures during visits as an impediment to deprescribing, several Spanish-speaking patients said language barriers exacerbated time pressures, discouraged them from asking questions, and made them less willing to accept deprescribing recommendations. For example, one Spanish-speaking patient recalled a doctor who “always needed to use an interpreter to talk to me ... didn’t understand anything and didn’t hear me... I [would] think about her not doing what’s best for me.” Another said she adjusted her medication on her own because she felt unable to get information from her doctor: “After starting [simvastatin], I would get dizzy. I started breaking it into smaller pieces because why would I need so much?”

As in other areas of medicine, racial and ethnic concordance was seen as important. Physicians perceived that concordance between physicians and patients could facilitate uptake of deprescribing recommendations, and discordance could impede uptake. For example, one physician said, “My patients who are African American maybe relate to me in a certain way and offer certain things that they may not offer to providers who don’t have racial concordance… Maybe that lends itself to their willingness to do certain things.” Patients and caregivers said it was important for educational materials about deprescribing to include photographs of people of different races and ethnicities “so they can see somebody that looks like them,” to be translated into different languages and to use language appropriate for people with varying degrees of health literacy.

Theme 2: Frame Deprescribing as Positive, Routine

Interviews revealed that the way a physician introduces deprescribing could cause patients and caregivers to perceive it as a withdrawal of care and reject it, as this comment from a caregiver suggests: “[The doctor] would say, ‘At your age... you probably have lived a good, long life.’… I didn’t like that because I would like to preserve her forever.” Physicians said they often found it difficult to explain the shift away from preventive therapies as a result of advanced age or dementia because it could be perceived by patients and caregivers as abandonment.

Some physicians identified approaches they used to overcome this perception and frame deprescribing as positive and routine. One physician said she “sets the stage” over time, contrasting long-term benefits of medications with immediate risks: “We’re going to [stop] some of these medications because... the benefit you get is down the road and the harm is right now.” This was echoed by a caregiver, who said, “I think it’s invaluable to re-evaluate every so often the effectiveness of [the] medications and whether or not they’re causing side effects that may not have occurred in the beginning.”

Theme 3: Align Deprescribing with Goals of Dementia Care, Including Symptom Management

Caregivers and physicians said an important foundation for discussing deprescribing was to educate patients and families about goals of care as dementia progresses, and introduce them to the idea that treatment of other conditions may be deintensified as a result of dementia. As one physician observed, “Our health care community has not done a good job at explaining that dementia is a life limiting diagnosis… It can come as a shock.” Indeed, some caregivers expressed surprise that medicines to treat diabetes or cardiovascular conditions could ever be stopped—and that there was a connection between progression of dementia and deprescribing medicines to treat other conditions—as revealed by the following statement by a caregiver: “If [the doctor] said, ‘We’re going to stop his diabetes meds,’ I’m thinking, ‘Is he cured?’”

Physicians used different strategies to acquaint patients and caregivers with focusing treatment on quality of life rather than prevention or cure. For example, “We should talk about what to expect over the next several years… and how we might change your treatment based on this.” Another physician explained the concept of lag time to benefit: “What is the time to benefit for statins?... What is the time to benefit for lowering your [hemoglobin] A1c?” The daughter of a man with advanced dementia recalled attending a caregivers’ conference that introduced this concept: “What medications do they really need… It’s not going to make things better.” As a result, she initiated a conversation about deprescribing with her father’s doctor.

For caregivers, it was important that physicians acknowledge the tradeoffs implicit in using medications for symptom management in dementia. As one caregiver commented: “It’s easy for a doctor to say… ‘Stop the Ativan… Ativan causes falls.’ … We’ve got to take that chance of her falling versus her being up all night and nobody getting [any] sleep.” Physicians said caregivers were often unaware that medications they were giving their family member for management of challenging symptoms could cause harm: “We do not discuss the risks of these medications... When I mention that to the family... [they say,] ‘Oh, really? Well, then, I don’t want to try it. I’d rather deal with the symptoms.’” Physicians emphasized the importance of respecting the caregivers’ expertise. As one physician said, “The ideal circumstance is to... let them direct… the decision to stop something… Recommending someone stop taking [a medication] and they’re not fully on board… is likely not to succeed, or you could tarnish the relationship.”

Theme 4: Provide Direct-to-Patient Educational Materials and Suggested Language

Patients and caregivers had positive perceptions of deprescribing in general and expressed enthusiasm about receiving educational materials to prime them for conversations with physicians. As one patient said, “It helps people bring up the subject if they don’t know how.” Patients and caregivers thought it was helpful for the materials to include examples of “questions you might want to ask” and symptoms that could be caused by medications. Physicians felt direct-to-patient materials positively would “provide information from another authoritative source” and lead to more productive conversations about deprescribing.

A small number of participants expressed concerns about direct-to-patient materials. One physician feared that such materials could exacerbate time pressures: “We all hate the ‘Talk to your doctor’… comment... I’ve got 15 minutes to talk about 10 things.” Some patients felt that receiving deprescribing brochures at home could cause anxiety for patients with cognitive impairment. For example: “One of my big mental problems at home is all this paperwork… Everybody thinks, ‘This is all we send you...’ But there’s 10 other people sending me things.”

Physicians expressed a strong desire for suggested language to use when talking about deprescribing with patients and families. For example, physicians described two communication challenges they often encountered. One is that patients are often told that they will need to take a medicine for life, without regard for the time to benefit: “The biggest thing is, ‘My cardiologist tells me I have to be on my statin forever.’ Or, ‘My endocrinologist told me [that] if I don’t treat my diabetes, I’m going to go blind...’ [Some] people feel like we’re withdrawing care.” The second, related challenge was helping a patient or caregiver decide whether a medication that may provide “any kind of possible benefit” was worth continuing. As one physician reflected, “To myself I’m saying, ‘Even if I prevent a stroke in their last year of life, having a stroke is... debilitating so there’s probably benefit somewhere in staying on that.”

Some physicians provided language that was incorporated into the physician tip sheets, such as “Few medications are prescribed forever.” Patients and caregivers also provided perspectives on language that was incorporated into the physician tip sheets. For example, a phrase linking aging to altered physiology—“Our bodies change over time and certain medicines may no longer be needed”—was acceptable to most patients and caregivers.

Theme 5: Engage Entire Health Care Team in Deprescribing

Participants agreed that other members of the health care team—particularly pharmacists—could help implement deprescribing and alleviate time pressures facing physicians. Physicians whose practices had embedded pharmacists or provided interdisciplinary, team-based care said these models provided additional, trusted team members to review patient medications and discuss deprescribing. Patients and caregivers who had received outreach from practice-based pharmacists to discuss their medications said they appreciated the service.

Physicians preferred receiving individualized deprescribing recommendations from pharmacists shortly before a patient visit, rather than generic pop-ups in the EMR about medication classes to avoid. Physicians also said they appreciated receiving guidance on tapering protocols from practice-based pharmacists, as they often felt unsure about how to taper and handle symptom recurrence.

Participants emphasized that it was important for physicians to provide close follow-up throughout the deprescribing process—a potential role for embedded pharmacists or other members of the health care team. One physician said it was crucial to reassure patients and caregivers: “This may make you nervous… but we are committed to seeing how you do a week from now and a month from now, and we can go back and change this.” Patients and caregivers often had concerns about symptom recurrence after medications were stopped and wanted to know that the physician would be accessible and make adjustments if needed. Ensuring access to a physician or pharmacist during deprescribing was seen as especially important for patients with cognitive impairment, who said that navigating automated clinic telephone menus or being directed to leave a message could be confusing and prevent them from discussing their concerns with physicians.

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study, feedback from patients, caregivers, and physicians informed the processes and content of a pragmatic, primary care–based deprescribing intervention for patients with dementia and MCC. Findings underscored the importance of using culturally appropriate language and materials that normalize deprescribing, earn patient and caregiver trust, educate patients and caregivers about changes that occur with aging and dementia, and acknowledge the tradeoffs of continuing medications to treat behavioral symptoms of dementia. Results also suggested that deprescribing processes in primary care should enlist the support of pharmacists, ensure close follow-up while tapering medications, and prepare clinicians with communication “pearls.”

A key finding was that physicians said they wanted to deprescribe but felt that they lacked the language and time to do so or were concerned that patients and caregivers would perceive deprescribing as withdrawal of care. As a result, 12 monthly tip sheets focused on deprescribing communication became the cornerstone of the clinician intervention. These incorporated language and concepts that patients and caregivers suggested, and included phrases such as “Deprescribing is a normal part of high quality care,” “Certain medicines may cause new side effects because our bodies change over time,” and “What are your primary goals for this year? Let’s adjust your medications to support those goals.” Caregivers also felt that physicians should use language that demonstrates respect for the day-to-day experience of caring for a person with dementia and involves them as partners in deprescribing. This finding has been affirmed by previous studies,27 in which caregivers expressed that they were “on their own” in managing behavioral symptoms of dementia.28 As a result, the OptiMize tip sheets incorporated the following suggestions for clinicians: “Listen first—the patient and their family and friends are the experts,” and “Practice shared decision-making—encourage patients and family members to communicate their feelings, ask questions, and even disagree.” These tip sheets can serve as a model for deprescribing communication guides for clinicians and are currently being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial.

As a first step toward ensuring that OptiMize would be acceptable to patients from diverse communities, we also began to explore deprescribing across different racial and ethnic groups. African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to suffer from dementia than Whites and to have higher morbidity burdens.29,30,31,32 African Americans and Hispanics may have comparable rates of polypharmacy to that of Whites,33 but lower income minorities have higher rates of polypharmacy and PIM use.34 Population-based studies suggest that African Americans have significantly less trust in providers and the health care system; poor communication with White providers may cause members of minority groups to be less willing to accept deprescribing recommendations.25, 35 Engaging members of minority cultural groups early in the development of deprescribing interventions may reduce disparities in dementia care.

Findings from this exploratory qualitative study cannot be generalized to African Americans and Hispanic communities as a whole. That being said, comments by participants of different races and ethnicities reflected enthusiasm for deprescribing and highlighted the importance of trust between physicians, patients, and caregivers. Importantly, some distinctions emerged around trust and communication. We found that language barriers and racial/ethnic discordance between patients and physicians may cause members of underrepresented minority groups to feel disempowered from asking questions and to reject deprescribing recommendations. This finding reflects nationally representative survey data, which found Blacks and other ethnic groups to be slightly less willing than Whites to stop a medication if their doctor recommended it.35 Patient-directed deprescribing educational materials should be translated into different languages and include photographs of people of different races and ethnicities. Interventions will likely require further modifications to address language, health literacy, and cultural characteristics of underrepresented minority groups.36,37,38

Patients and caregivers in our study were interested in receiving direct-to-patient education about deprescribing. Interventions that involve direct-to-patient educational brochures have been among the most successful to date,9, 39 possibly because they improve the ability of patients and caregivers to have meaningful discussions with health professionals.40 We are not aware of previous deprescribing materials developed specifically for patients with cognitive impairment and caregivers. Some physicians were concerned that encouraging patients and caregivers to “talk with the doctor” about deprescribing would place further demands on time-limited primary care visits. However, other studies that used pre-visit materials to prime older adults and caregivers for conversations with physicians showed that communication became more patient-centered without extending visit duration.41 Pre-visit educational materials about deprescribing may help patients and caregivers focus visits on issues that matter to them,42 an essential part of patient-centered care, without imposing additional time demands.

Two of our findings are more challenging to implement in the current primary care environment. First, we found widespread support for the involvement of other health care professionals, particularly pharmacists, in deprescribing. While some delivery systems (e.g., Veterans Administration and other integrated systems) include clinical pharmacists in the care team, payment reforms will be needed to fully integrate pharmacists into primary care.43 Second, we found that patients, caregivers, and physicians were worried about symptom recurrence after stopping medications—a concern that echoes previous qualitative research24, 44—and it was important to maintain close communication throughout the deprescribing process. Medicare initiated nonvisit-based payment for chronic care management in 2015, which could help facilitate deprescribing by compensating for coordinated health care provided by clinical pharmacists outside of patient visits.45

Strengths of this study include recruitment of participants in geographically diverse areas with large African American and Hispanic populations and interviews conducted in Spanish when needed. An important next step will be to confirm our findings in other populations of African American and Hispanic patients, including those from multicultural backgrounds. Physicians practiced in a range of settings, academic and non-academic. We note the limitation that patients, caregivers, and physicians who participated in the study may differ from those who did not. For example, medical mistrust may discourage patients from participating in research, and this may affect our understanding of how trust in the health care system affects uptake of deprescribing.46

CONCLUSIONS

By eliciting the perspectives of stakeholders, this qualitative study gained key insights regarding content and process elements, including culturally competent aspects, to inform the OptiMize intervention and increase awareness of deprescribing in primary care for patients with dementia and MCC.

References

Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716-24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.6.716.

Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, Hanlon JT, Hubbard R, Walker R et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):401-7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663.

Castelino RL, Hilmer SN, Bajorek BV, Nishtala P, Chen TF. Drug Burden Index and potentially inappropriate medications in community-dwelling older people: the impact of Home Medicines Review. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(2):135-48. https://doi.org/10.2165/11531560-000000000-00000.

Hill-Taylor B, Sketris I, Hayden J, Byrne S, O’Sullivan D, Christie R. Application of the STOPP/START criteria: a systematic review of the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults, and evidence of clinical, humanistic and economic impact. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38(5):360-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12059.

Brown JD, Hutchison LC, Li C, Painter JT, Martin BC. Predictive Validity of the Beers and Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP) Criteria to Detect Adverse Drug Events, Hospitalizations, and Emergency Department Visits in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):22-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13884.

Jansen J, Naganathan V, Carter SM, McLachlan AJ, Nickel B, Irwig L et al. Too much medicine in older people? Deprescribing through shared decision making. BMJ. 2016;353:i2893. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2893.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(4):738-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12386.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324.

Ostini R, Jackson C, Hegney D, Tett SE. How is medication prescribing ceased? A systematic review. Med Care. 2011;49(1):24-36. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef9a7e.

Clyne B, Fitzgerald C, Quinlan A, Hardy C, Galvin R, Fahey T et al. Interventions to Address Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(6):1210-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14133.

Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Kouladjian L, Hilmer SN. Deprescribing trials: methods to reduce polypharmacy and the impact on prescribing and clinical outcomes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):237-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.006.

Alldred DP, Kennedy MC, Hughes C, Chen TF, Miller P. Interventions to optimise prescribing for older people in care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009095. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009095.pub3.

Forsetlund L, Eike MC, Gjerberg E, Vist GE. Effect of interventions to reduce potentially inappropriate use of drugs in nursing homes: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-11-16.

Child A, Clarke A, Fox C, Maidment I. A pharmacy led program to review anti-psychotic prescribing for people with dementia. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:155. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-155.

Lang PO, Vogt-Ferrier N, Hasso Y, Le Saint L, Drame M, Zekry D et al. Interdisciplinary geriatric and psychiatric care reduces potentially inappropriate prescribing in the hospital: interventional study in 150 acutely ill elderly patients with mental and somatic comorbid conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(4):406 e1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.03.008.

Sawan M, Reeve E, Turner J, Todd A, Steinman MA, Petrovic M et al. A systems approach to identifying the challenges of implementing deprescribing in older adults across different health-care settings and countries: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(3):233-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512433.2020.1730812.

Thompson W, Reeve E, Moriarty F, Maclure M, Turner J, Steinman MA et al. Deprescribing: Future directions for research. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15(6):801-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.08.013.

Martinez AI, Spencer J, Moloney M, Badour C, Reeve E, Moga DC. Attitudes toward deprescribing in a middle-aged health disparities population. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.014.

Primm AB, Cabot D, Pettis J, Vu HT, Cooper LA. The acceptability of a culturally-tailored depression education videotape to African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(11):1007-16.

Sarkisian CA, Brusuelas RJ, Steers WN, Davidson MB, Brown AF, Norris KC et al. Using focus groups of older African Americans and Latinos with diabetes to modify a self-care empowerment intervention. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(2):283-91.

Carbone ET, Rosal MC, Torres MI, Goins KV, Bermudez OI. Diabetes self-management: perspectives of Latino patients and their health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(2):202-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.003.

Glaser BG. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. In: Strauss AL, editor. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co.; 1967.

Green AR, Lee P, Reeve E, Wolff JL, Chen CCG, Kruzan R et al. Clinicians’ Perspectives on Barriers and Enablers of Optimal Prescribing in Patients with Dementia and Coexisting Conditions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(3):383-91. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2019.03.180335.

Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN. Beliefs and attitudes of older adults and carers about deprescribing of medications: a qualitative focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(649):e552-60. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685669.

Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, Collins TC, Gordon HS, O’Malley K et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):146-52.

Balkrishnan R, Dugan E, Camacho FT, Hall MA. Trust and satisfaction with physicians, insurers, and the medical profession. Med Care. 2003;41(9):1058-64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Mlr.0000083743.15238.9f.

Todd A, Jansen J, Colvin J, McLachlan AJ. The deprescribing rainbow: a conceptual framework highlighting the importance of patient context when stopping medication in older people. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):295. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0978-x.

Kerns JW, Winter JD, Winter KM, Kerns CC, Etz RS. Caregiver Perspectives About Using Antipsychotics and Other Medications for Symptoms of Dementia. Gerontologist. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx042.

Steenland K, Goldstein FC, Levey A, Wharton W. A meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease incidence and prevalence comparing African-Americans and caucasians. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50(1):71-6.

Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):367-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.001.

Cheng Y, Ahmed A, Zamrini E, Tsuang DW, Sheriff HM, Zeng-Treitler Q. Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias in Older African American and White Veterans. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-191188.

Lin PJ, Emerson J, Faul JD, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, Fillit HM et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Knowledge About One’s Dementia Status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16442.

Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in Prescription Drug Use Among Adults in the United States From 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.13766.

Bazargan M, Smith J, Movassaghi M, Martins D, Yazdanshenas H, Salehe Mortazavi S et al. Polypharmacy among underserved older African American adults. J Aging Res. 2017;2017.

Reeve E, Wolff JL, Skehan M, Bayliss EA, Hilmer SN, Boyd CM. Assessment of Attitudes Toward Deprescribing in Older Medicare Beneficiaries in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4720.

Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr., Martinez CR, Jr. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prev Sci. 2004;5(1):41-5.

Chin MH, Walters AE, Cook SC, Huang ES. Interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):7S-28S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558707305413.

Coletti DJ, Stephanou H, Mazzola N, Conigliaro J, Gottridge J, Kane JM. Patterns and predictors of medication discrepancies in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(5):831-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12387.

Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949.

Patient empowerment--who empowers whom? Lancet. 2012;379(9827):1677. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60699-0.

Wolff JL, Roter DL, Boyd CM, Roth DL, Echavarria DM, Aufill J et al. Patient-Family Agenda Setting for Primary Care Patients with Cognitive Impairment: the SAME Page Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(9):1478-86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4563-y.

Gobat N, Kinnersley P, Gregory JW, Robling M. What is agenda setting in the clinical encounter? Consensus from literature review and expert consultation. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(7):822-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.024.

Mossialos E, Courtin E, Naci H, Benrimoj S, Bouvy M, Farris K et al. From “retailers” to health care providers: Transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy. 2015;119(5):628-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.02.007.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793-807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0106-8.

Fixen DR, Linnebur SA, Parnes BL, Vejar MV, Vande Griend JP. Development and economic evaluation of a pharmacist-provided chronic care management service in an ambulatory care geriatrics clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(22):1805-11. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp170723.

Healey P, Stager ML, Woodmass K, Dettlaff AJ, Vergara A, Janke R et al. Cultural adaptations to augment health and mental health services: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1953-x.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patient, family, and clinician advisory panels for their guidance. We also thank Mahesh Maiyani, MBA, for his contribution in identifying patients and caregivers for the qualitative study.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was conducted with grant support from the National Institute on Aging under award numbers R21AG057289 (Bayliss, Boyd) and K23AG054742 (Green). The funding agency did not have a role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research was approved by the institutional review boards of Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO) and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Boyd writes a chapter on multimorbidity for UpToDate, for which she receives a royalty. Dr. Reeve is supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship and co-authors a chapter on deprescribing for UpToDate, for which she receives a royalty. Dr. Maciejewski owns stock in Amgen. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

Presented as a poster at the 2019 North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Green, A.R., Boyd, C.M., Gleason, K.S. et al. Designing a Primary Care–Based Deprescribing Intervention for Patients with Dementia and Multiple Chronic Conditions: a Qualitative Study. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 3556–3563 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06063-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06063-y