Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Universal worsening of retinopathy after starting insulin therapy in Type 2 diabetes has been suggested in previous work.

Methods

We studied 294 such patients for up to 5 years to evaluate retinal changes and define the factors affecting progression of retinopathy. Yearly retinal photographs were graded using the EURODIAB system.

Results

Prior to insulin therapy, 26.2% (77/294) of the patients had minimal non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), 3.7% (n=11) had moderate NPDR and 1% (n=3) had severe NPDR. Over the first 3 years of insulin therapy, significant progression occurred in 36 subjects (12.6%). This comprised 5/193 (2.6%) without any retinopathy at baseline, 22/77 (28.5%) with minimal NPDR and 6/11 with moderate NPDR (54.5%) (χ2=56.1, p<0.001). In a control group of 70 patients who remained on oral hypoglycaemic agents, nine patients had significant worsening of retinopathy over 3 years. Over 5 years, 22/127 (17.3%) of patients (9/95 without and 13/32 with retinopathy at baseline [χ2=16.2, p<0.001]) had significant progression of retinopathy. Higher baseline HbA1c (p=0.002) and lower initial decrease in HbA1c (p=0.007) were each independent predictors of greater retinopathy progression over this period. There was no significant worsening of visual acuity in patients whose retinopathy progressed.

Conclusions/interpretation

After initiation of insulin treatment in Type 2 diabetes, clinically significant worsening of retinopathy over a 3-year period was uncommon in those with no retinopathy (2.6%) but occurred in 31.8% of patients with any retinopathy at baseline. The risk of serious worsening of retinopathy after insulin therapy is started in all patients with Type 2 diabetes may have been previously overestimated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute tightening of blood glucose control can bring about worsening of diabetic retinopathy in both types of diabetes mellitus. This was reported in several large studies [1, 2, 3, 4] and was confirmed in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) [5, 6, 7]. The DCCT study showed deterioration of retinopathy in patients with Type 1 diabetes during the first 3 to 12 months with intensive therapy, followed by a beneficial effect, which increased in magnitude over time.

Commencement of insulin therapy in Type 2 diabetes has been associated with a two-fold increased risk of worsening of retinopathy and a three-fold increased risk of blindness or visual impairment [8]. This requires confirmation, as there have been few long-term studies on the progression of retinopathy in this group.

The aim of the present study was to assess the retinal changes and visual acuity in patients with Type 2 diabetes, from the time of initiation of insulin therapy, for a period of up to 5 years.

Subjects and methods

Participants

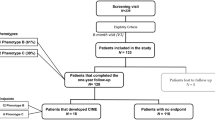

All patients with Type 2 diabetes who started insulin treatment between 1996 and 1999 and were still attending the diabetic clinic at Newcastle Diabetes Centre were identified from the clinic database. The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) and all patients gave informed consent. All the following criteria had to be met for patients to be included in the study: age at diagnosis of diabetes older than 30 years, duration of diabetes at the commencement of insulin therapy more than 2 years, retinal photographs of both eyes at baseline (time of initiation of insulin) and yearly thereafter, and change of treatment from oral hypoglycaemic agents to insulin between 1996 and 1999. Those who died within 3 years of follow-up, or had unclear pictures or non-diabetic eye diseases interfering with the assessment of photographs, were excluded from the study. We identified 390 patients who started on insulin because of inadequate glycaemic control, of whom 294 patients met the criteria for inclusion in the study. Of the 96 patients excluded, 37 patients had died within 3 years of starting insulin treatment, 17 had poor quality pictures, 10 had non-diabetic eye diseases, 4 were already registered blind, and 28 had incomplete data. Six patients who were included in the study died during the follow-up period but had sufficient information over at least 3 years. To provide information on rate of progression of retinopathy in non-insulin-treated subjects, we selected a group of 70 patients with Type 2 diabetes who were on maximal oral hypoglycaemic agents for 3 years. It was not feasible to match precisely for duration of diabetes and HbA1c, and hence the group should not be regarded as strict control subjects for the insulin-treated patients.

Measurements

All patients had yearly retinal photographs with mydriasis during the study period (January 1995 to January 2003) in the quality-controlled screening programme reported previously [9]. Macula- and disc-centred views were taken through dilated pupils. The photographs were graded for the study by a single observer (C. S. Arun) against standard photographs using the EURODIAB grading system [10, 11] (Table 1) and each patient was assigned to the level determined by the worst eye. As Polaroid photographs were used from 1995 to 2000 and two-field digital retinal images have been used since 2000, a sub-study was done to test whether photographic medium affected assessment of EURODIAB scoring. The yearly rates of change in grade of retinopathy from 1996 to 2001 were 0.09, 0.07, 0.13, 0.15, 0.18 and 0.22 respectively, indicating a gradual progression through the years and no significant effect on grading of photographic modality in 2000. This was further confirmed by considering the percentage of individuals showing no change, worsening or showing improvement each year (Polaroid [1998–1999] 81.7%, 15.3%, 3.0%, Polaroid [1999–2000] 76.8%, 19.1%, 4.0%, Polaroid [2000–2001] 76.2%, 19.5%, 4.3%, digital [2001–2002] 75.8%, 22.2%, 2%).

Retinopathy was classified into four categories for analysis: no retinopathy (EURODIAB grade 0), minimal non-proliferative retinopathy (NPDR; grade 1), moderate to severe NPDR (grade 2 to 3) and proliferative retinopathy (grade 4 to 5). Patients with laser scars, fibrous bands and pre-retinal or vitreous haemorrhages were assigned to the proliferative category. Grading of maculopathy was based on the presence of exudates in the macular region according to a published grading system: level 0, no maculopathy; 1, questionable (less than 50% certainty of presence of exudates); 2, exudate greater than one disc diameter from fixation; 3, circinate ring of exudates within macula greater than one disc area in size but not within one disc diameter of fixation; 4, exudates within one disc diameter of fixation or presence of focal or grid photocoagulation scars or both; 90, photographs ungradeable [12].

Inter- and intra-observer variation validation

A random sample of 25 sets of photographs was examined by a consultant ophthalmologist (R. Pandit). There was 100% agreement with the primary observer in detection of sight-threatening retinopathy according to the definition used.

The primary grader re-graded 25 sets of photographs selected randomly at the end of the study to assess the within-observer variation. There was 94% (47/50 eyes) agreement in the grades assigned, with a kappa coefficient (K) of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.83–0.95).

In addition, the same 25 sets of photographs were independently graded by the Retinal Grading Centre at Hammersmith Hospital, London, which serves as the UK national grading centre. There was 92% (46/50 eyes) agreement in grading between primary grader and the reference standard with a K of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.92). When retinopathy was classified according to the worst eye, there was disagreement in grading in only one eye (K=0.93±0.07).

Visual acuity (VA) was measured in each eye using Snellen chart. The value was recorded as the decimal value (i.e. 6/60=0.1, 6/36=0.16, 6/24=0.25, 6/18= 0.33, 6/12=0.5, 6/9=0.66 and 6/6=1) [11].

Definitions

Sight-threatening maculopathy was defined as presence of hard exudates within one disc diameter of fixation or presence of focal or grid photocoagulation or both.

Significant progression was defined as the development of moderate NPDR or higher grades of retinopathy on the EURODIAB grading system or sight-threatening maculopathy on follow-up. Administration of laser therapy was considered as significant progression in those patients with moderate or severe NPDR at baseline.

Statistical analysis

MINITAB statistical software was used to analyse data. Serum triglyceride concentrations and albumin creatinine ratio (ACR) were normalised by logarithmic transformation before analysis. Values are given as means ± SD or median (range). Differences between groups were assessed by Student’s t test or chi square test (χ2) as appropriate. The risk factors independently influencing progression of retinopathy over a 5-year period were analysed by binary logistic regression analysis. A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Subject characteristics

At baseline (time of commencement of insulin therapy), 65.7% of patients (193/294) had no retinopathy, 26.2% (77/294) had minimal NPDR, 3.7% (n=11) moderate NPDR and 1% (n=3) severe NPDR (Table 2). We excluded from further analysis 3.4% (n=10) of the patients because they had received previous laser treatment in one or both eyes. For 284 patients, 3-year follow-up information was available, and 5-year information was available in 127 patients.

Three-year follow-up data

Mean HbA1c at baseline was 10.0±1.3% and decreased to 8.3±1.2% after 1 year, 8.4±1.3% after 2 years, and 8.4±1.4% after 3 years. Mean blood pressure was 146±22/81±11 mm Hg at baseline and 141±20/75±11 mm Hg at 3 years.

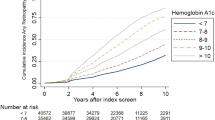

Significant progression of retinopathy occurred in 36 patients (12.6%), consisting of 5/193 (2.6%) with no retinopathy at baseline, 22/77 (28.5%) with minimal NPDR and 6/11(54.5%) with moderate NPDR (Fig. 1). Of these patients, 18 had sight-threatening maculopathy, for which 12 had received laser therapy by the end of the third year.

Cumulative incidence of patients with significant progression of retinopathy over 5 years categorised according to baseline diabetic retinopathy. Progression in the severe NPDR group was defined as the administration of laser therapy. Severe NPDR (□), moderate NPDR (▼), minimal NPDR (△), no retinopathy (■)

The presence of any retinopathy at baseline was noted to be a strong predictor of significant progression of retinopathy over this period (χ2=56.1, p<0.001). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that significant progression was also independently influenced by longer duration of diabetes (p=0.017; odds ratio=1.09, 95% CI: 1.02–1.17. Baseline blood pressures were similar in the two groups, i.e. non-progressors and progressors (145±22 and 147±20 mm Hg systolic), and a similar number of patients from each group were on treatment for hypertension (52% vs 59%). Of the non-progressors, 52% were on ACE inhibitors in comparison with 33% of progressors.

Five-year follow-up data

In the group of 127 subjects examined at 5 years, there was no detectable retinopathy in 57 subjects, minimal NPDR in 47 subjects, moderate NPDR in eight subjects, severe NPDR in eight subjects, and proliferative retinopathy in two subjects. The remaining five patients had received laser treatment. Of those patients with moderate or severe NPDR, nine had sight-threatening maculopathy. Significant progression over this period was noticed in 22/127 (17.3%) patients. Only 9.4% (9/95) of those free of retinopathy at baseline developed significant retinopathy over the follow-up period of 5 years, whereas 40.6% (13/32) of those with retinopathy progressed (χ2=16.2, p<0.001).

Progressors had a significantly greater duration of diabetes (8±5 vs 11±5, p=0.04) and mean HbA1c during follow-up (8.2±0.9 vs 8.7±0.9, p=0.03). Higher baseline HbA1c (p=0.039, odds ratio=2.49, 95% CI: 1.05–5.91) and a smaller decrease in HbA1c (p=0.005, odds ratio=0.40, 95% CI: 0.21–0.76) were noted to be independent risk factors for retinopathy progression (Table 3).

Progression in non-insulin-treated patients

A total of 70 non-insulin-treated Type 2 diabetic patients (38 men) were studied over a 3-year period (Table 2). At baseline, 48/70 (68.6%) patients were free of retinopathy, 19 had minimal NPDR, and three had moderate NPDR. Significant progression occurred in nine (12.9%) patients. All nine had minimal NPDR at baseline (χ2=22.5, p<0.0001). The progressors also had higher HbA1c (9.2±2.0 vs 8.1±1.2) and longer duration of disease (7.3±1.5 years vs 6.1±3.3 years). When comparing patients who had retinopathy at baseline, similar progression over 3 years was noted in those remaining on oral agents and those starting insulin treatment (9/22 vs 31/91 respectively).

Discussion

In Type 2 diabetes patients starting on insulin, we observed negligible risk of significant progression in those with no retinopathy at baseline (2.6% over a 3-year period). However, 28.6% with minimal NPDR and 54.5% with moderate NPDR at baseline progressed. The overall rate of progression was 12.6% over the first 3 years and 11.0% over the next 2 years. Longer duration of diabetes, higher baseline HbA1c and higher mean HbA1c were found to be independent risk factors for developing sight-threatening retinopathy. The cumulative incidence of laser therapy rose gradually from 1.4% to 5.5% over the total follow-up period of 5 years.

These findings are in contrast to previous suggestions that change of treatment from oral drugs to insulin is associated with a two-fold increased risk of retinopathy progression within the first 3 years [8]. Other studies suggested that, although the initial risk of progression is higher in those with retinopathy at baseline, significant progression would still occur continuously in all grades of retinopathy, i.e. from no retinopathy to moderate NPDR in the first 2 years after initiation of insulin therapy [13]. The relationship between glycaemia and retinopathy was not demonstrable in the same patient group after 3 years [14]. However, it should be noted that in the entire population of the Wisconsin Epidemiological Study of Diabetic Retinopathy, the 10-year progression to proliferative retinopathy varied from 7% in those with no retinopathy at baseline to 81% in those with moderate NPDR at baseline [15]. Thus, regardless of the treatment, there is a tendency for retinopathy to progress steadily once it develops. This was observed in the present study in patients who already had some retinopathy at baseline, of whom a similar proportion progressed regardless of their treatment (41% in those on oral agents and 34% in those on insulin therapy).

The steady progression of retinopathy over the first 3 years after insulin initiation occurred despite improved glycaemic control. This could possibly be explained by hyperglycaemic memory phenomenon shown in previous studies [16]. The EDIC study suggested that the events leading to development of retinopathy may be triggered during periods of poor glycaemic control and hence retinopathy continues to progress even after the establishment of improved glycaemic control. This was also observed in the DCCT, where the intensively treated patients had early worsening of retinopathy even though they ultimately had a marked reduction in the risk of subsequent progression [7].

There was no significant reduction in visual acuity in insulin initiators when compared with the non-insulin-treated patients in this population who received annual retinal screening [9]. The results are in direct contrast to the only previous study in insulin-treated subjects, which showed a three times increased risk of visual impairment over a 3-year follow-up period [8].

Some of the earlier studies used seven-field stereo photographs as opposed to two-field. However, the validity of the EURODIAB protocol and grading system used in this study has been shown to be comparable to the ETDRS protocol [10, 11, 17]. It is suitable for large epidemiological studies and could be particularly useful in Type 2 diabetes patients who are less likely to have proliferative retinopathy. It should be noted that progressors were classified in our study as those who developed sight-threatening retinopathy (moderate to severe NPDR in EURODIAB grading), which would be equivalent to level 41 or above with Wisconsin classification. Previous studies have defined significant progression as greater than three levels of progression in Wisconsin grading [8, 13, 18]. The difference in grading systems used is unlikely to have made any significant impact on the identification of sight-threatening retinopathy.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

albumin creatinine ratio

- DCCT:

-

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial

- NPDR:

-

non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- UKPDS:

-

United Kingdom Prospective Diabetic Study

References

Agardh CD, Eckert B, Agardh E (1992) Irreversible progression of severe retinopathy in young type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients after improved metabolic control. J Diabetes Complications 6:96–100

KROC (1988) Diabetic retinopathy after two years of intensified insulin treatment. Follow-up of the Kroc Collaborative Study. JAMA 260:37–41

Lauritzen T, Frost-Larsen K, Larsen HW, Deckert T (1985) Two-year experience with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in relation to retinopathy and neuropathy. Diabetes 34:74–79

Roysarkar TK, Gupta A, Dash RJ, Dogra MR (1993) Effect of insulin therapy on progression of retinopathy in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Ophthalmol 115:569–574

DCCT (1993) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med 329:977–986

DCCT (1995) The effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the progression of diabetic retinopathy in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 113:36–51

DCCT (1995) The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes 44:968–983

Henricsson M, Nilsson A, Janzon L, Groop L (1997) The effect of glycaemic control and the introduction of insulin therapy on retinopathy in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 14:123–131

Pandit RJ, Taylor R (2002) Quality assurance in screening for sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy. Diabet Med 19:285–291

Aldington SJ, Kohner EM, Meuer S, Klein R, Sjolie AK (1995) Methodology for retinal photography and assessment of diabetic retinopathy: the EURODIAB IDDM complications study. Diabetologia 38:437–444

Sjolie AK, Stephenson J, Aldington S et al. (1997) Retinopathy and vision loss in insulin-dependent diabetes in Europe. The EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study. Ophthalmology 104:252–260

Harding SP, Broadbent DM, Neoh C, White MC, Vora J (1995) Sensitivity and specificity of photography and direct ophthalmoscopy in screening for sight threatening eye disease: the Liverpool Diabetic Eye Study. BMJ 311:1131–1135

Henricsson M, Berntorp K, Berntorp E, Fernlund P, Sundkvist G (1999) Progression of retinopathy after improved metabolic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Relation to IGF-1 and hemostatic variables. Diabetes Care 22:1944–1949

Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Cruickshanks KJ (1994) The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of diabetic retinopathy. XIV. Ten-year incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 112:1217–1228

Henricsson M, Berntorp K, Fernlund P, Sundkvist G (2002) Progression of retinopathy in insulin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 25:381–385

White NH, Cleary PA, Dahms W, Goldstein D, Malone J, Tamborlane WV (2001) Beneficial effects of intensive therapy of diabetes during adolescence: outcomes after the conclusion of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). J Pediatr 139:804–812

Chaturvedi N, Sjoelie AK, Porta M et al. (2001) Markers of insulin resistance are strong risk factors for retinopathy incidence in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 24:284–289

Henricsson M, Janzon L, Groop L (1995) Progression of retinopathy after change of treatment from oral antihyperglycemic agents to insulin in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 18:1571–1576

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr Steve Aldington and his team at the Retinopathy Grading Centre at Hammersmith Hospital, London, for his assistance with the quality assessment of the grading. The retinal screeners of the Newcastle Diabetes Centre carried out all of the photography upon which this assessment was based, and we are also grateful to the medical and nursing staff of the Centre, whose cooperation was essential for the study. C. S. Arun was supported by a research fellowship from Eli Lilly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arun, C.S., Pandit, R. & Taylor, R. Long-term progression of retinopathy after initiation of insulin therapy in Type 2 diabetes: an observational study. Diabetologia 47, 1380–1384 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-004-1473-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-004-1473-9