Abstract

Providing age-based non-contributory pensions to the elderly has become a common policy in many middle-income countries. The rationale behind these programs is to protect beneficiaries, who do not qualify for a contributory pension, from extreme poverty once they are too frail to earn a living. This paper analyzes whether one such program, Mexico’s 70 y Más, had any effect on the food vulnerability of the elderly. Using the age and locality size cutoffs for eligibility, we find negative and significant effects on food vulnerability for single elderly men, especially for those in the lower wealth quintiles. While the results for single elderly women are of the same sign, they are small in magnitude and not statistically significant. We also find negative and significant effects on the food vulnerability for the poorest elderly couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We calculate this figure for 2013 using the working-age population (18–65 years old) projection from the Mexican Population Council (CONAPO) and the number of salaried workers from the Mexican Employment and Occupation Survey (ENOE) for that year.

Results for multi-generational households, which are available from the authors upon request, are similar in sign to the results for single elderly individuals, but they are not statistically significant.

Two papers provide evidence on the impacts of non-contributory pensions on household food consumption for other Latin American countries. Gonzalez-Rozada and Ruffo (2016) find that the addition of a non-contributory pillar to the Argentinian social security system has a positive and statistically significant effect on household food expenditures. In contrast, Hernani-Limarino and Mena (2016) find no significant effects of Renta Dignidad, a non-contributory pension program in Bolivia, on per capita household food consumption.

Aguila et al. (2017) find that the number of days since the last program payment has a negative and significant effect on food expenditures for the federal non-contributory pension, which is paid bimonthly, whereas it has no significant effect for the Yucatan non-contributory pension, paid monthly.

For instance, Aguila et al. (2017) report results for three variables about whether the household: (1) often runs out of food; (2) is often hungry; and (3) often not eat for a day. All these variables are coded as a four-point scale, reflecting the frequency in which the household experiences lack of food (1 \(=\) always, 4 \(=\) never). In contrast, our measure of food vulnerability is a dummy for whether any member in the household had to eat only one meal a day due to lack of resources.

In theory, other types of workers, like the self-employed, are allowed to participate voluntarily in IMSS, but in practice, very few do (Levy 2008).

Please refer to the program performance report “Informe de la Evaluacion Especifica de Desempeño del Programa 70 y Más 2010–2011” by CONEVAL.

We calculated these figures using the 2010 Mexican Income and Expenditure Survey (Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares, ENIGH, collected by INEGI.

If the two types of pensions were mutually exclusive, total pension coverage would be 67% in 2010 and 80% in 2016. Thus, some overlap between the two seems to exist. The data used by CONSAR is the 2016 ENIGH survey.

Please refer to the blogpost by CONSAR “Quienes y cuantos mexicanos tienen acceso a una pension?” accessed on Feb. 19, 2019.

This heterogeneity is mostly due to variation in the minimum age requirement and the transfer amount between countries, with Mexico showing a relatively high eligibility age (70 years old) and a smaller transfer amount (500 MXP per month) in 2011.

Please refer to their paper for specific references on these validation studies.

For this variable, as reported in the table, we have a slightly lower sample size due to some missing values.

We only observe whether the individual receives any government transfers, without distinguishing between programs.

To classify household into wealth quintiles, we follow Filmer and Pritchett (2001) and construct a principal components household wealth index based on 20 household variables that measure the durable asset holdings and quality of the dwelling. We construct this index using the full 10% Census sample.

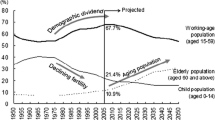

See “Situacion demografica de Mexico, 2002”, CONAPO, available at http://www.gob.mx/conapo.

In this paper, our sample is very different from the one considered by either Amuedo-Dorantes and Juarez (2015) or Juarez (2009). The first study focuses on the impact of 70 y Más program on the private monetary support received by elderly individuals in localities with less than 2500 inhabitants, the smallest in the country and the first ones to participate in the program. Conversely, the second study focuses on the crowding out of private transfers caused by a state-level non-contributory pension program for elderly adults in Mexico City, the largest city in the country.

References

Aguila E, Kapteyn A, Smith J (2014) Effects of income supplementation on health of the poor elderly: the case of Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(1):70–75

Aguila E, Kapteyn A, Perez-Arce F (2017) Consumption smoothing and frequency of benefit payments of cash transfer programs. Am Econ Rev 107(5):430–35

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Juarez L (2015) Old-age government transfers and the crowding out of private gifts: the 70 and above program for the rural elderly in Mexico. South Econ J 81(3):782–802

Ballard T, Kepple A, Cafiero C (2013) The food insecurity experience scale: development of a global standard for monitoring hunger worldwide. Technical paper, FAO, Rome. http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-fs/voices/en/

FAO (2012) Escala latinoamericana y caribea de seguridad alimentaria (ELCSA): Manual de uso y aplicaciones. Technical report, FAO Regional Office, Santiago. http://www.rlc.fao.org/es/publicaciones/elcsa/

Filmer D, Pritchett LH (2001) Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data- or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 38(1):115–132

Galiani S, Gertler P, Bando R (2016) Non-contributory pensions. Labour Econ 38:47–58

Gonzalez-Rozada M, Ruffo H (2016) Non-contributory pensions and savings: evidence from Argentina. Technical report, IDB working paper series no. 629

Hernani-Limarino W, Mena G (2016) Intended and unintended effects of unconditional cash transfers: the case of Bolivias Renta Dignidad. Techical report, IDB working paper series no. 631

Juarez L (2009) Crowding out of private support to the elderly: evidence from a demogrant in Mexico. J Public Econ 93(3–4):454–463

Juarez L, Pfutze T (2015) The effects of a noncontributory pension program on labor force participation: the case of 70 y Más in Mexico. Econ Dev Cultural Change 63(4):685–713

Levy S (2008) Good intentions, bad outcomes: social policy, informality and economic growth in Mexico. Brookings Institution Press, Washington

Levy S, Schady N (2013) Latin America’s social policy challenge: education, social insurance, redistribution. J Econ Perspect 27(2):193–218

Perez-Escamilla R, Paras P, Vianna R (2012) Food security measurement through public opinion polls: the case of Elcsa-Mexico. Technical report, FAO, Rome, presented at the international scientific symposium on food and nutrition security information: from valid measurement to effective decision-making

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Both authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Juarez, L., Pfutze, T. Can non-contributory pensions decrease food vulnerability? The case of Mexico. Empir Econ 59, 1865–1882 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01702-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01702-8