Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of using transvaginal mesh to correct uterine prolapse by hysteropexy.

Methods

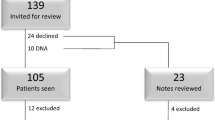

This was a single-center, prospective study of 40 subjects with bothersome uterine prolapse. Inclusion criteria were bothersome perception of a vaginal bulge on Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory short form (PFDI-20) and having a Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q) point C of −2 or worse. Exclusionary criteria included inability to consent, history of pelvic malignancies, or any prior prolapse repair. Eligible subjects were treated with transvaginal mesh hysteropexy between March 2016 and July 2018 for a primary outcome of composite success, which was defined by a POP-Q point C value of −2 or higher, PFDI−20 question 3 indicating no bothersome perception of prolapse, and no retreatment. Secondary outcomes included responses to condition-specific and quality-of-life questionnaires, satisfaction/regret, and complications.

Results

Transvaginal mesh hysteropexy was performed in 40 subjects. The majority (68%) had advanced stage (III/IV) uterine prolapse. At a median follow-up of 12 months, there was an 84% composite success, and considering only anatomic criteria (POP-Q point C < –1), there was a 92% success. No subject required reintervention for recurrent or persistent uterine prolapse. There were no cases of mesh exposures. In terms of safety, one subject required a blood transfusion for symptomatic anemia (Clavien-Dindo grade II), and one subject reported de novo dyspareunia from a perineal band that was released in office at 6 months (grade IIIa), but otherwise there were no serious immediate or late complications. There were significant improvements in both condition-specific and quality-of-life assessments from baseline. Subject satisfaction and acceptance for the procedure were high.

Conclusions

In this single-center case series of 40 women with bothersome uterovaginal prolapse, transvaginal mesh hysteropexy appears safe and effective for correcting advanced stage uterine prolapse at the short term. A future multicenter controlled trial would be needed to determine efficacy against native tissue repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1160–6.

McCall ML. Posterior culdeplasty: surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy; a preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1957;10:595–602.

Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–34.

Sze EHM, Miklos J, Partoll L, Rout T, Karram MM. Sacrospinous ligament fixation with transvaginal needle suspension for advanced pelvic organ prolapse and stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;80:94–6.

Barber MD, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL, Bump RC. Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site-specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1402–11.

Marchionni M, Bracco GL, Checcucci V, et al. True incidence of vaginal vault prolapse: thirteen years of experience. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:679–84.

Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103–9.

Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;4:249–53.

Dietz V, van der Vaart CH, van der Graaf Y, Heintz P, Koops SE. One-year follow-up after sacrospinous hysteropexy and vaginal hysterectomy for uterine descent: a randomized study. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:209–16.

Nieminen K, Hiltunen R, Takala T, et al. Outcomes after anterior vaginal wall repair with mesh: a randomized, controlled trial with 3-year follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:235e1–8.

Altman D, Väyrynen T, Engh ME, et al. Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic-organ prolapse. NEJM. 2011;364:1826–36.

Withagen M, Milani A, den Boon J, Vervest H, Vierhout M. Trocar-guided mesh compared with conventional vaginal repair in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):242–50.

FDA takes action to protect women’s health, orders manufacturers of surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse to stop selling all devices. US Food and Drug Administration. 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-action-protect-womens-health-orders-manufacturers-surgical-mesh-intended-transvaginal. Accessed 7 Oct 2019.

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10–7.

Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:103–13.

Herzog AR, Diokno AC, Brown MB, Normolle DP, Brock BM. Two-year incidence, remission, and change patterns of urinary incontinence in noninstitutionalized older adults. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M67–74.

Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, et al. A short form of the pelvic organ prolapse/urinary incontinence sexual questionnaire (PISQ-12) [discussion abstract]. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14:164–8.

Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:98–101.

Sung VW, Kauffman N, Raker CA, Myers DL, Clark MA. Validation of decision-making outcomes for female pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):575.e1–6.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Gutman RE, Rardin CR, Sokol ER, et al. Vaginal and laparoscopic mesh hysteropexy for uterovaginal prolapse: a parallel cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(1):38.e1–38.e11.

Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2016–24.

van IJsselmuiden M, Oudheusden A, Veen P, et al. Hysteropexy in the treatment of uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy versus sacrospinous hysteropexy-a multicentre randomised controlled trial (LAVA trial). BJOG. 2020;127(10):1284–93.

Schulten S, Detollenaere R, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational follow-up of a multicenter randomized trial. BMJ. 2019;366:l5149.

Fatton B, Amblard J, Debodinance P, Cosson M, Jacquetin B. Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of a new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift technique)-a case series multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18:743–52.

Elmer C, Altman D, Engh ME, et al. Trocar-guided transvaginal mesh repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet GynecoI. 2009;113:117–26.

Nager C, Visco A, Richter H, et al. Effect of vaginal mesh hysteropexy vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse. JAMA. 2019;322(11):1054–65.

Withagen M, Milani A, de Leeuw J, Vierhout M. Development of de novo prolapse in untreated vaginal compartments after prolapse repair with and without mesh: a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BJOG. 2012;119:354–60.

Milani A, Withagen M, Vierhout M. Outcomes and predictors of failure of trocar-guided vagina mesh surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:440.e1–8.

Barber M, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al. Defining success after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:600–9.

Withagen MI, Vierhout ME, Hendriks JC, Kluivers KB, Milani AL. Risk factors for exposure, pain, and dyspareunia after tension-free vaginal mesh procedure. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):629–3.

Khandwala S. Transvaginal mesh surgery for pelvic organ prolapse: one-year outcome analysis. J Gyn Surg. 2019;35(1):12–8.

Meriwhether K, Balk E, Antosh D, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(4):505–22.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Khandwala: Project/protocol development, manuscript writing/editing.

J. Cruff: Data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial disclaimers/conflict of interest statement

Dr. Khandwala is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Coloplast, and Medtronics. He is also an expert witness in the Johnson and Johnson medicolegal multidistrict litigation. Dr. Cruff has no conflicts of interest. Funding was provided through an Investigator-Initiated Study program by Coloplast Inc. (Humlebaek, Denmark). Coloplast, however, had no role in the study design, data analysis, or writing of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khandwala, S., Cruff, J. Prospective analysis of transvaginal mesh hysteropexy in the treatment of uterine prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 32, 2241–2247 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04590-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04590-0