Abstract

Purpose

Despite their relevance in clinical medicine, the extension and activity of the bone marrow (BM) cannot be directly evaluated in vivo. We propose a new method to estimate these variables by combining structural and functional maps provided by CT and PET.

Methods

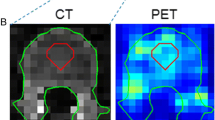

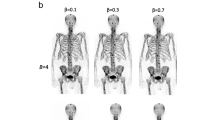

BM extension and glucose uptake were estimated in 102 patients undergoing whole-body PET/CT because of a history of nonmetastatic melanoma. Image analysis assumed that the BM is surrounded by compact bone. An iterative optimization scheme was applied to each CT slice to identify the external border of the bone. To identify compact bone, the algorithm measured the average Hounsfield coefficient within a two-pixel ring located just inside the bone contour. All intraosseous pixels with an attenuation coefficient lower than this cut-off were flagged as 1, while the remaining pixels were set at 0. Binary masks created from all CT slices were thus applied to the PET data to determine the metabolic activity of the intraosseous volume (IBV).

Results

Estimated whole-body IBV was 1,632 ± 587 cm3 and was higher in men than in women (2,004 ± 498 cm3 vs. 1,203 ± 354 cm3, P < 0.001). Overall, it was strictly correlated with ideal body weight (r = 0.81, P = 0.001) but only loosely with measured body weight (r = 0.43, P = 0.01). The average FDG standardized uptake value (SUV) in the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae was 2.01 ± 0.36, Accordingly, intraosseous voxels with SUV ≥1.11 (mean spine SUV − 2.5 × SD) were considered as active “red” BM and those with SUV <1.11 as “yellow” BM. Estimated red BM volume was 541 ± 195 ml, with a higher prevalence in the axial than in the appendicular skeleton (87 ± 8 % vs. 10 ± 8 %, P < 0.001). Again, red BM volume was higher in men than in women (7.8 ± 2.2 vs. 6.7 ± 2.1 ml/kg body weight, P < 0.05), but in women it occupied a greater fraction of the IBV (32 ± 7 % vs. 36 ± 10 %, P < 0.05). Patient age modestly predicted red BM SUV, while it was robustly and inversely correlated with red BM volume.

Conclusion

Our computational analysis of PET/CT images provides a first estimation of the extension and metabolism of the BM in a population of adult patients without haematooncological disorders. This information might represent a new window to explore pathophysiology the BM and the response of BM diseases to chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Knowles S, Hoffbrand AV. Bone-marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy (1). Br Med J. 1980;281:204–5.

Agool A, Glaudemans AW, Boersma HH, Dierckx RA, Vellenga E, Slart RH. Radionuclide imaging of bone marrow disorders. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:166–78.

Desai AG, Thakur ML. Radiopharmaceuticals for spleen and bone marrow studies. Semin Nucl Med. 1985;15:229–38.

Datz FL, Taylor Jr A. The clinical use of radionuclide bone marrow imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 1985;15:239–59.

Wahren B, Gahrton G, Hammarstrom S. Nonspecific crossreacting antigen in normal and leukemic myeloid cells and serum of leukemic patients. Cancer Res. 1980;40:2039–44.

Mitchell DG, Burk DL, Vinitski S, Rifkin MD. The biophysical basis of tissue contrast in extracranial MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:831–7.

Duda SH, Laniado M, Schick F, Strayle M, Claussen CD. Normal bone marrow in the sacrum of young adults: differences between the sexes seen on chemical-shift MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:935–40.

Kugel H, Jung C, Schulte O, Heindel W. Age- and sex-specific differences in the 1H-spectrum of vertebral bone marrow. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:263–8.

Basu S, Houseni M, Bural G, Chamroonat W, Udupa J, Mishra S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging based bone marrow segmentation for quantitative calculation of pure red marrow metabolism using 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography: a novel application with significant implications for combined structure-function approach. Mol Imaging Biol. 2007;9:361–5.

Blebea JS, Houseni M, Torigian DA, Fan C, Mavi A, Zhuge Y, et al. Structural and functional imaging of normal bone marrow and evaluation of its age-related changes. Semin Nucl Med. 2007;37:185–94.

Fan C, Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Houseni M, Chamroonrat W, Basu S, Kumar R, et al. Age-related changes in the metabolic activity and distribution of the red marrow as demonstrated by 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography. Mol Imaging Biol. 2007;9:300–7.

Shreeve WW. Use of isotopes in the diagnosis of hematopoietic disorders. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:173–9.

Kumar R, Alavi A. Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET in the management of breast cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:1113–22.

Jhanwar YS, Straus DJ. The role of PET in lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1326–34.

Robinson JD, Lupkiewicz SM, Palenik L, Lopez LM, Ariet M. Determination of ideal body weight for drug dosage calculations. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1983;40:1016–9.

Chan TF, Vese LA. Active contour without edges. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2001;10:266–77.

Abramowitz M, Stegun IA. Handbook of mathematical functions. National Bureau of Standards. Applied Mathematics Series. Washington DC: Tenth Printing; 1972. p. 1020.

Dirac P. Principles of quantum mechanics. 4th ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1958.

Courant R, Hilbert R. Method of mathematical physics, vol. I. New York: Interscience; 1953.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10.

Choplin RH, Farber JM, Buckwalter KA, Swan S. Three-dimensional volume rendering of the tendons of the ankle and foot. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2004;8:175–83.

Mechanik N. Untersuchungen ueber das Gewicht des knochenmark des Menschen. Z Gesamte Anat. 1926;79:58–99.

ICRP. Report of the task group on reference man. ICRP publication 23. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1975.

Valentin J. Basic anatomical and physiological data for use in radiological protection: reference values. A report of age- and gender-related differences in the anatomical and physiological characteristics of reference individuals. ICRP Publication 89. Ann ICRP. 2002;32:5–265.

Bonner H. The blood and lymphoid organs. In: Rubin E, Farber JL, editors. Pathology. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1988. p. 1014

Atkinson HR. Bone marrow distribution as a factor in estimating radiation to the blood-forming organs: a survey of present knowledge. J Coll Radiol Aust. 1962;6:149–54.

Woodard HQ, Holodny E. A summary of the data of Mechanik on the distribution of human bone marrow. Phys Med Biol. 1960;5:57–9.

Ellis RE. The distribution of active bone marrow in the adult. Phys Med Biol. 1961;5:255–8.

Cristy M. Active bone marrow distribution as a function of age in humans. Phys Med Biol. 1981;26:389–400.

Custer RP, Ahlfeldt FE. Studies on the structure and function of bone marrow. II. Variations in cellularity in various bones with advancing years of life and their relative response to stimuli. J Lab Clin Med. 1932;17:960–2.

Tavassoli M. Bone marrow: The seedbed of blood. In: Wintrobe MM, editor. Blood, pure and eloquent sh.5. New York: Mc.Graw-Hill Book Company; 1980.

Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI, Davis SD. Percutaneous CT biopsy of chest lesions: an in vitro analysis of the effect of partial volume averaging on needle positioning. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:273–8.

Aston JA, Cunningham VJ, Asselin MC, Hammers A, Evans AC, Gunn RN. Positron emission tomography partial volume correction: estimation and algorithms. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:1019–34.

Schadendorf D, Dorn-Beineke A, Borelli S, Riethmuller G, Pantel K. Limitations of the immunocytochemical detection of isolated tumor cells in frozen samples of bone marrow obtained from melanoma patients. Exp Dermatol. 2003;12:165–71.

Elder DE. Thin melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:342–6.

Denninghoff VC, Falco J, Kahn AG, Trouchot V, Curutchet HP, Elsner B. Sentinel node in melanoma patients: triple negativity with routine techniques and PCR as positive prognostic factor for survival. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:438–44.

Thie JA. Clarification of a fractional uptake concept. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:711–2.

Thie JA. Understanding the standardized uptake value. Its methods and implications for usage. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1431–4.

Chin BB, Green ED, Turkington TG, Hawk TC, Coleman RE. Increasing uptake time in FDG-PET: standardized uptake values in normal tissues at 1 versus 3 h. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:118–22.

Czernin J, Satyamurthy N, Schiepers C. Molecular mechanisms of bone 18F-NaF deposition. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1826–9.

Agool A, Schot BW, Jager PL, Vellenga E. 18F-FLT PET in hematologic disorders: a novel technique to analyze the bone marrow compartment. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1592–8.

Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–206.

Emery JL, Follett CF. Regression of bone marrow haemopoiesis from the terminal digits in the foetus and infant. Br J Haematol. 1964;10:485–9.

Vogler JB, Murphy WA. Bone marrow imaging. Radiology. 1988;168:679–93.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata Ministeriale 2009 and Progetto Conto Capitale 2011); Regione Liguria (Ricerca Finalizzata anno 2009); Compagnia di San Paolo; Fondazione CARIGE; AIRC; Associazione Italiana Leucemie, Sezione Ligure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sambuceti, G., Brignone, M., Marini, C. et al. Estimating the whole bone-marrow asset in humans by a computational approach to integrated PET/CT imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 39, 1326–1338 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-012-2141-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-012-2141-9