Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to assess for changes in quality of life (QOL) among cancer patients who undergo radiotherapy (RT) and to identify factors that influence QOL in this group.

Materials and methods

Three hundred sixty-seven cancer patients who received curative RT were investigated using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire at the start of RT, end of RT, and 1 and 6 months post-RT.

Results

The patients were 49 % women, 51 % men, and median age at diagnosis was 57 years (range, 16–86 years). Compared to pre-RT, at the end of RT, the global health status score (p < 0.001), nausea/vomiting (p < 0.001), and apetite loss scores (p < 0.001) were significantly poorer. Compared to the end of RT, at 1 and 6 months post-RT, global health status, all functional, and all symptom scores were significantly improved (p < 0.001). Patient sex influenced scores for pain (p = 0.036), appetite loss (p = 0.027), and financial difficulty (p = 0.003). Performance status influenced scores for global health status (p = 0.006), physical functioning (p < 0.001), cognitive functioning (p = 0.001), and role functioning (p = 0.021). Comorbidity influenced fatigue score (p < 0.001). Cancer stage influenced scores for physical functioning (p = 0.001), role functioning (p = 0.010), and fatigue (p < 0.001). Treatment modality (chemoRT vs. RT alone) influenced scores for physical functioning (p = 0.016), fatigue (p < 0.001), nausea/vomiting (p = 0.009), and appetite loss (p < 0.001); and RT field influenced scores for nausea/vomiting (p = 0.001), appetite loss (p = 0.003), and diarrhea (p = 0.037). Radiotherapy dose functioning (p < 0.001), cognitive functioning (p < 0.001), social functioning (p < 0.001), fatigue (p < 0.001), and pain (<60 vs ≥60 Gy) had an effect on scores for physical functioning (p < 0.001), role functioning (p < 0.001), emotional (p < 0.001), insomnia (p < 0.001), constipation (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

While RT negatively affects cancer patients’ QOL, restoration tends to be rapid and patients report significant improvement by 1 month post-RT. Various patient- and disease-specific factors and RT modality affect QOL in this patient group. We advocate measuring cancer patients’ QOL regularly as part of routine patient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is being diagnosed more and more frequently worldwide, and advances in treatment are extending survival time for cancer patients. The traditional endpoints in cancer clinical trials typically include tumor control rate, overall survival, or disease-free survival; however, it is also important to consider quality of life (QOL) for this patient group. Over the past 30 years, cancer researchers have used various methods to evaluate the efficacy of therapeutic interventions based on their impacts on health-related QOL [1]. These efforts have led to a relatively recent shift in the aim of cancer treatments from strictly prolonging life to also maintaining QOL for as long as possible.

The Core Quality of Life Questionnaire developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30) is an instrument for assessing health-related QOL in cancer patients [2]. This instrument is reliable, validated, and feasible to use in research and is the questionnaire most widely used in cancer clinical trials worldwide [3]. Cross-cultural adaptability of the EORTC QLQ-C30 has been evaluated with testing in more than 24 countries [2, 4, 5].

Radiotherapy (RT) is used in approximately half of all cancer cases and is applied as a component of curative and/or palliative treatment. While RT can have health benefits for cancer patients, its side effects can negatively impact QOL. There is a need to objectively examine the ways in which RT affects QOL in this patient group. The aims of this study were to assess for changes in QOL among cancer patients who receive RT and to identify factors that influence QOL in this patient group.

Materials and methods

The Departmental Ethics Committee of Cumhuriyet University’s School of Medicine approved this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Three hundred sixty-seven cancer patients who underwent RT in the Radiation Oncology Department of Cumhuriyet University School of Medicine between January 2010 and June 2012 were enrolled. All cancer patients who received curative RT were considered eligible. Those who received palliative RT were excluded.

In all cases, RT was performed using a linear accelerator device (Varian Clinac DHX, Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Three-dimensional conformal RT planning was done using ECLIPS version 8.6 software (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Doses of RT ranged from 45 to 74 Gy.

Prior to treatment, each patient’s performance status was scored according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Scoring System [6]. Cancers were classified based on system or body site affected: central nervous system, head and neck, thorax, breast, gastrointestinal system, genitourinary system, gynecological, skin and soft tissue, and hematological malignancies. Stage of disease was evaluated according to the 2010 TNM classification developed by the International Union Against Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Radiotherapy field was categorized as one of six sites: cranium, head and neck, breast, thorax, abdomen, or pelvis. In addition to these data, demographic and histopathological data for the 367 patients were obtained from hospital records.

Quality of life scale

Quality of life was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3.0, a 30-item questionnaire. The components of the EORTC QLQ-C30 are global health status, five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, social), and nine symptom scales/items (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, financial difficulties). Patients’ responses were scored according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual [7]. Scores for the symptom components were linearly transformed to a scale of 0 to 100. A high score for a functional scale represented a relatively high level of functioning, whereas a high score for a symptom scale represented greater severity of symptoms or financial impact [8]. Each patient completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 at four different time points: the start of RT (T1); the end of RT (T2); 1 month after completion of RT (T3); 6 months after completion of RT (T4).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 15.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Medians and frequencies were calculated for patient demographics. Questionnaire scores were compared across the four time points using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Effects of multiple variables (gender, presence of comorbidity, ECOG performance status, cancer stage, RT field, and RT treatment modality) on changes in QOL over time were analyzed using two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (MANOVA). A p ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. The patients were 181 (49 %) men and 186 (51 %) women. Their median age at time of cancer diagnosis was 57 years (range, 16–86 years). Ranked in order of frequency, the cancer classifications were breast (n = 101, 28 %), gastrointestinal (n = 93, 25 %), head and neck (n = 55, 15 %), genitourinary (n = 30, 8 %), lung (n = 26, 7 %), central nervous system (n = 23, 6 %), gynecological (n = 19, 5 %), hematological (n = 12, 3 %), and skin and soft tissue (n = 8, 2 %). One hundred and ninety-five patients (53 %) were treated with RT alone, the remaining 172 (47 %) with chemoradiotherapy (chemoRT). Regarding RT field, 101 patients (27 %) were irradiated in the breast, 91 (25 %) in the pelvis, 65 (18 %) in the head and neck, 54 (15 %) in the abdomen, 32 (9 %) in the thorax, and 24 (6 %) in the cranium.

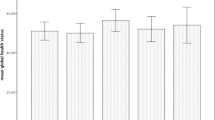

Table 2 summarizes the EORTC QLQ-C30 QOL results at the four time points. The questionnaire response rates were 100 % (n = 367) at T1, 100 % (n = 366) at T2, 96 % (n = 351) at T3, and 86 % (n = 316) at T4. Compared to scores at T1, at T2, the mean global health status score (p = 0.024) were significantly lower, and mean nausea/vomiting scores (p = 0.034) and mean apetite loss score (p < 0.001) were significantly higher. However, compared to findings at T2, at T3 and T4, the mean global health status scores and all mean functional scores were significantly higher and all mean symptom scores were significantly lower.

Table 3 shows comparisons of questionnaire scores at the four time points with patients categorized by sex, presence of comorbidity, and ECOG performance status. Analysis revealed that patient sex had an effect on scores for pain, appetite loss, and financial difficulty; performance status had an effect on scores for global health status, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, and role functioning; comorbidity had an effect on fatigue score.

Table 4 lists comparisons of questionnaire scores at the four time points with patients categorized by cancer stage, treatment modality (RT alone versus chemoRT), and RT field. Analysis revealed that cancer stage had an effect on scores for physical functioning, role functioning, and fatigue, with patients at more advanced stages having worse scores for these components. Treatment modality had an effect on scores for physical functioning, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and appetite loss, with patients who received chemoRT having poorer scores. However, QOL scores of patients received chemotherapy after radiotherapy were not significantly changed (p > 0.050). Radiotherapy field had an effect on scores for nausea/vomiting, appetite loss, and diarrhea, with the groups irradiated in the head and neck, abdomen and pelvis having the worst scores for these elements. Radiotherapy dose (<60 versus ≥60 Gy) had an effect on scores for physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, fatifue, pain, insomnia, and constipation (Table 5). Higher radiotherapy dose (≥60 Gy) had a negative effect on QOL scores such as physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, fatifue, pain, insomnia, and constipation. However, there was not a negative effect on the scores of cognitive functioning and social functioning.

Discussion

To date, researchers have tended to focus on measuring global and/or cancer-specific QOL in cancer patients, whereas our study sample included various forms and stages of cancer. We found that RT affected our cancer patients’ QOL negatively, but we also noted significant restoration of QOL by 1-month post-treatment. Further, we observed that QOL in our sample was affected not only by RT treatment modality but also by patient-specific factors (sex, performance status, comorbidity) and disease-specific factors (cancer stage and RT field).

There are several methods for treating cancer, and QOL is an important consideration when making medical decisions for these patients [9, 10]. In addition to the treatment choice that is ultimately made, the decision-making process itself can affect QOL [11]. As a curative treatment, RT is administered over weeks and has early and late side effects; thus, it is not surprising that this therapy can have long-term impacts on QOL. Longitudinal studies have the potential to demonstrate changes in cancer patients’ QOL over time. The intervals of measurement in these investigations must be long enough for changes to occur, but also short enough to be able to ascribe changes to specific causes. The longer the duration between two measurements, the larger are the effects of uncontrollable influencing factors [1].

Budischewski et al. [1] used the EORTC QLQ-C30 to study QOL in 61 breast cancer patients at the beginning of RT and 6 weeks after RT was completed. These authors achieved a response rate of 68 % at their post-RT time evaluation, whereas our response rates for the same questionnaire at 1 and 6 months post-RT were 96 and 86 %, respectively. From the start of RT to 6 weeks after RT, Budischewski et al. reported significant improvement in role functioning, significantly poorer cognitive functioning, and observed no changes in global health status or physical, emotional, or social functioning [1].

In contrast, Bansal et al. [12] used the EORTC QLQ-C30 to evaluate 45 patients with head and neck cancer at three time points: the start of RT, fourth week of RT, and 1 month after RT. These authors found that global health status and physical, social, and emotional functioning all declined significantly during RT. One month after RT, they observed improvement in all the functional scale scores, but none had returned to pre-RT levels. Bansal et al. also reported that their patients’ scores for role and cognitive functioning remained high during RT (i.e., in week 4 of therapy), and they observed no significant changes in these scales from pre-RT to post-RT. The same study revealed that, compared to pre-RT, the scores for fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, and financial difficulties all increased significantly during the course of RT. At 1 month after RT, the scores for fatigue, pain, insomnia, and appetite loss remained high, whereas those for nausea/vomiting and dyspnea were significantly improved. Bansal et al. observed no changes in their patients’ EORTC QLQ-C30 scores for constipation and diarrhea from pre-RT to 1 month after RT.

De Graeff et al. [13] prospectively evaluated changes in QOL for 107 patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck who underwent post-operative RT. The authors used the EORTC QLQ-C30 as well as the QLQ-H&N35, a questionnaire specific for patients with head and neck cancer and applied these instruments before RT and 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after RT. Their results for EORTC QLQ-C30 at 6 months post-RT revealed significant deterioration in the scores for physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, and fatigue; however, by 6 months later (12 months after RT), all these scores had improved significantly. Our findings with the EORTC QLQ-C30 in 367 patients with various forms of cancer were similar to those of De Graeff et al. Compared to the start of RT, at the end of RT, compared to baseline, at the end of RT, we observed significantly lower mean scores for global health status and significantly higher mean scores for nausea/vomiting and appetite loss. By 1 and 6 months post-RT, mean global health status scores, all mean functional scores, and mean symptom scores had improved significantly. We suspect that the regular measurements of QOL played a part in this.

Other researchers have also examined factors that influence QOL in cancer patients treated with RT. Tiv et al. [14] studied 207 patients with rectal cancer who were treated with pre-operative RT or pre-operative chemoRT. They applied the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-CR38, a questionnaire specific for colorectal cancer patients, at a median follow-up 4.6 years. Results from the EORTC QLQ C-30 indicated that patient sex had a significant influence on the scores for some function scales and symptom scales/items. Specifically, the authors found that men felt better physically and were less fatigued by RT than women 4.6 years after the beginning preoperative treatment. Elumelu et al. [15] investigated 100 patients with head and neck cancer and applied the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 (mentioned above) at the beginning and end of RT. At the end of RT, they observed that females’ mean scores for role functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, dyspnea, and constipation were higher than those for males, whereas males had higher mean scores for fatigue, pain, insomnia, appetite loss, diarrhea, and financial difficulties. Males and females had almost equal scores for global health status, physical functioning, emotional functioning, and nausea/vomiting. However, Elumelu et al. [15] found no significant differences between the sexes for any of these scores. In contrast, our analysis revealed that patient sex influenced EORTC QLQ-C30 results for appetite loss, pain, and financial difficulties. Compared with the baseline measurement at the start of RT, females’ mean scores for pain and financial difficulties were significantly higher than males’ at T2 and T3 (end of RT and 1 month post-RT, respectively), and males’ mean scores for appetite loss, pain, and financial difficulties were all significantly higher than females’ at T4 (6 months post-RT).

Research has identified performance status as a good predictor of cancer patients’ QOL [16, 17]. It has been shown that the number and severity of symptoms experienced by lung cancer patients increase as performance status deteriorates [18]. Guzelant et al. [19] evaluated correlations between EORTC QLQ-C30 scores and Karnofsky performance scale status (KPS) in 194 lung cancer patients and found that KPS was most strongly associated with certain functional scale scores. The strongest associations were with physical functioning, role functioning, and fatigue, whereas the weakest were with nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and emotional functioning. We analyzed relationships between ECOG performance status and QOL in patients with a variety of cancer types, and our findings were similar to those of Guzelant et al [19]. ECOG performance status was associated with global health status, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, and role functioning on the EORTC QLQ-C30. For each of these scales, poorer ECOG performance status was associated with lower function. We observed no correlations between performance status and symptoms scores in our patient group.

It is logical to speculate that cancer patients with comorbidity who undergo RT would have poorer QOL than those without comorbidity. However, we found that fatigue score was only component of the EORTC QLQ-C30 for which there was a significant difference between these groups, with greater fatigue reported by patients with comorbidity.

Elumelu et al. [15] evaluated EORTC QLQ-C30 results according to disease stage in their patients with head and neck cancer, and found that mean scores for global health status and all functional scales were significantly lower for late-stage (III and IV) patients than for early-stage (I and II) patients. They also observed that late-stage patients had significantly higher scores for all symptom scales/items than early-stage patients. McMillan et al. [20] used the EORTC QLQ C-30 to evaluate the relationship between QOL and survival in 152 patients with gastroesophageal cancer. They found that, compared to patients with early-stage disease, those in late stages had significantly poorer scores for global health status, social functioning, fatigue, and appetite loss. Our analysis revealed that disease stage had an effect on certain EORTC QLQ-C30 scores; specifically, patients with later-stage cancer had poorer mean scores for physical functioning, role functioning, and fatigue.

In the above-mentioned study that compared EORTC QLQ-C30 scores for rectal cancer patients who underwent preoperative RT or preoperative chemoRT, Tiv et al. [14] observed that the chemoRT group had significantly lower scores for role functioning, social functioning, and global health status, whereas the RT group had a significantly higher score for diarrhea. Taphoorn et al. [21] evaluated the impact of chemoRT versus RT alone in patients with brain tumors and compared EORTC QLQ-C30 and BN-20 (a brain cancer module) scores at the start of RT, during RT, end of RT, and monthly thereafter during treatment until progression. During RT, they observed more side effects (nausea/vomiting, appetite loss, constipation) in the group of 248 patients treated with chemoRT than in the 242 patients treated with RT alone. In our analysis of cancer patients’ EORTC QLQ-C30 scores, we found that chemoRT had an effect on physical functioning, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and appetite loss. The group that received chemoRT had significantly poorer mean scores for these components. These findings were likely related to side effects of chemotherapeutic agents. However, we observed that QOL scores were unchanged in patients who received chemotherapy after radiotherapy. Because of small number of patients, we did not perform QOL assessments according to each tumor type.

Radiation dose in incidence of radiation-related side effects is an important parameter. Higher radiotherapy dose (≥60 Gy) had a negative effect on QOL scores such as physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue, pain, insomnia, constipation. However, there was not a negative effect on the scores of cognitive functioning and social functioning.

Radiotherapy side effects are known to be associated with certain body sites of irradiation; thus, RT field is considered an important determinant of QOL [22]. In our study, at the end of RT, we observed the following: (i) the group irradiated in the abdomen had the highest mean score for nausea/vomiting; (ii) the groups irradiated in the abdomen and head/neck, respectively, had significantly higher mean scores for appetite loss than all other groups; (iii) the group irradiated in the pelvis had a significantly higher mean score for diarrhea than all other groups.

QOL scores gradually deteriorate during head-neck irradiation, and they improve over time after radiotherapy. These deteriorations may result in discontinuation of the treatment. Regularly QOL measurements of patients with cancer during their treatments may be beneficial in earlier detection of deterioration in QOL. Therefore, we strongly believe that physicians may improve QOL with supportive treatment and/or care. At the same time, QOL data may have value in daily practice. Routine QOL measurements of oncology patients visiting the outpatients department, with information provided to physicians, have been shown to have a positive effect on physician-patients communication. In some patients, these measurements improved QOL and emotional functioning [23]. Published studies that longitudinal measurements improve functional and symptom-related scores of QOL [24, 25].

Our study indicates that RT affects QOL negatively for patients with various forms of cancer, and that QOL improves significantly for these patients within the first 6 months after RT. We strongly believe that the very process of conducting QOL assessments can improve life quality for cancer patients. We suggest that QOL should be measured regularly in this group as part of routine patient management.

References

Budischewski K, Fischbeck S, Mose S (2008) Quality of life of breast cancer patients in the course of adjuvant radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer 16:299–304

Aaronson NK, Cull A, Kaasa S et al (1996) The European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) modular approach to quality of life assessment in oncology: and update. In: Spilker B (ed) Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials, 2nd edn. Raven Press, New York, pp 179–189

Gotay CC, Wilson M (1998) Use of quality-of-life outcome assessments in current cancer clinical trials. Eval Health Prof 21:157–178, Review

Kaasa S, Bjordal K, Aaronson N et al (1995) The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30): validity and reliability when analysed with patients treated with palliative radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer 31A:2260–2263

Hjermstad MJ, Fossa SD, Bjordal K, Kaasa S (1995) Test/retest study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer core quality-of-life questionnaire. J Clin Oncol 13:1249–1254

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC et al (1982) Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 5:649–655

Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Sullivan M (1995) EORTC QLO-C30 scoring manual. EORTC Data Center, Belgium

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376

Terrell JE, Ronis DL, Fowler KE et al (2004) Clinical predictors of quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Acta Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130:401–408

Prezioso D, Galasso R, Di Martino M, Iapicca G (2007) Prostate cancer treatment and quality of life. Recent Results Cancer Res 175:251–265

O’Rourke ME (2007) Choose wisely: therapeutic decisions and quality of life in patients with prostate cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 11:401–408

Bansal M, Monanti BK, Shah N, Chaudhry R, Bahadur S, Shukla NK (2004) Radiation related morbidities and their impact on quality of life in head and neck cancer patients receiving radical radiotherapy. Qual Life Res 13:481–488

De Graeff A, de Leeuw JRJ, Ros WJG, Hordijk GJ, Blijham GH, Winnubst JAM (2000) Long-term quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 110(1):98–106

Tiv M, Puyraveau M, Mineur L et al (2010) Long-term quality of life in patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative (chemo)-radiotherapy within a randomized trial. Cancer/Radiothér 14:530–534

Elumelu TN, Adenipekun AA, Abdus-salam AA, Bojude AD, Campbell OB (2011) Quality Of life in patients with head and neck cancer on radiotherapy treatment at Ibadan. Researcher 3(8):1–10

Buccheri GF, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M, Brunelli C (1995) The patient’s perception of his own quality of life might have an adjunctive prognostic significance in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 12:45–58

Osoba D, Murray N, Gelmon K et al (1994) Quality of life appetite, and weight change in patients receiving dose-intensive chemotherapy. Oncology 8:61–65

Hopwood PH, Stephens RJ (1995) Symptoms at presentation for treatment in patients with lung cancer: implications for the evaluation of palliative treatment. Br J Cancer 71:633–636

Guzelant A, Goksel T, Ozkok S, Tasbakan S, Aysant T, Bottomley A (2004) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: an examination into the cultural validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the EORTC QLO-C30. Eur J Cancer Care 13:135–144

McKernan M, McMillan DC, Anderson JR, Angerson WJ, Stuart RC (2008) The relationship between quality of life (EORTC QLO-C30) and survival in patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer 98:888–893

Taphoorn MJ, Stupp R, Coens C et al (2005) Health-related quality of life in patients with glioblastoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 6:937–944

Takahashi T, Hondo M, Nishimura K et al (2008) Evaluation of quality of life and psychological response in cancer treated with radiotherapy. Radiat Med 26:396–401

Taphoorn MJB, Sizoo EM, Bottomley A (2010) Review on quality of life issues in patients with primary brain tumors. Oncologist Neuro-Oncol 15:618–626

Yamashita H, Omori M, Okuma K et al (2014) Longitudinal assessments of quality of life and late toxicities before and after definitive chemoradiation for esophageal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 44:78–84

Bottomley A, Tridello G, Coens C et al (2014) An international phase 3 trial in head and neck cancer: quality of life and symptom results: EORTC 24954 on behalf of the EORTC Head and Neck and the EORTC Radiation Oncology Group. Cancer 120:390–398

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yucel, B., Akkaş, E.A., Okur, Y. et al. The impact of radiotherapy on quality of life for cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 22, 2479–2487 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2235-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2235-y