Abstract

The recent demographic trends in Western Europe imply tremendous structural change and are likely to heavily impact regional development. Against this background, we focus on entrepreneurial activities at universities and analyze regional and university specific determinants of the emergence of university entrepreneurship across regions that are differently challenged by demographic change. We underpin this quantitative assessment with interviews conducted in six case study regions with university staff responsible for technology transfer and the promotion of entrepreneurship to get some tentative insights about the perception of how demographic change might impact the entrepreneurial potential of universities. The results demonstrate that regional population decline is negatively related to entrepreneurial activities at universities. Furthermore, even university start-ups whose business idea is driven by detecting market opportunities related to demographic change are not more likely to emerge in regions that are especially challenged by demographic change. Finally, our interviews suggested that demographic change seems to play no role in the day-to-day work of technology transfer offices.

Zusammenfassung

Deutsche Regionen sind unterschiedlich stark vom demografischen Wandel betroffen. Der Entwicklungstrend impliziert tiefgreifende Veränderungen der regionalen Struktur und beeinflusst die regionale Entwicklung. Vor diesem Hintergrund ist die Idee dieses Beitrags zu untersuchen, inwieweit Hochschulen, als wesentlicher Faktor regionaler Entwicklung, einen Beitrag leisten können, um negativen Konsequenzen von regionalen Schrumpfungsprozessen entgegenzuwirken. Dabei betrachten wir wie sich demografischer Wandel auf das Entstehen von Hochschulausgründungen auswirkt. Diese Analyse wird durch Erkenntnisse auf Basis von Experteninterviews in sechs Fallstudienregionen bereichert. Im Mittelpunkt der Interviews standen Unterschiede bezüglich des Förderinstrumentariums sowie der Wahrnehmung des demografischen Wandels als „Challenge“ für die Gründungsförderung an Hochschulen. Es zeigt sich im Ergebnis, dass Hochschulausgründungen im Allgemeinen als auch im Hinblick auf solche bei denen das Geschäftsmodell einen expliziten Demografiebezug aufweist kaum in Schrumpfungsregionen stattfinden. Ferner wird die Auswirkung demografischen Wandels auf das Hochschulausgründungsgeschehen in der Arbeit der Technologietransferstellen kaum wahrgenommen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The presented chain of reasoning corresponds with the interview statements given by the staff of the research and technology transfer office from the six case study regions (for details, see Chapter 5).

In the analyzed period between 2007 and 2014 the grant was between 800 and 2500 €. Expenses for material and equipment were covered for up to 17,000 € in the case of team start-ups. Another program within the framework of the EXIST initiative is the so-called “EXIST Research Transfer”. In contrast to the start-up grant scheme the projects are not yet in the seed-stage and it is largely unclear which kind of concrete products and services will be developed based on the research within the project. Therefore, on the one hand it is not possible to evaluate whether the funded projects are related to demographic change. On the other hand the projects as such are less relevant for our research question since services and products that can be developed out of the projects are not very predictable.

In this respect, we thank Patrick Guette and Baran Erdemsiz for excellent research support.

The screening of the projects was carried out by two persons. A subsample of 50 projects was screened by both persons separately in order to rule out that individual differences in the perception of the relatedness to demographic change drive the classification procedure. There was a full overlap in the classifications. A list of DREPs that received a start-up grant can be obtained upon request. A detailed definition for DREP is given in the Appendix A5.

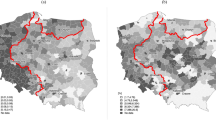

NUTS is the abbreviation for the French “Nomenclature des Unités Territoriales de Statistique” (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics). This geocode standard has been developed by the European Union, and it shows the subdivisions of EU countries for statistical purposes. EUROSTAT, the statistical office of the EU, has established a hierarchy of at least three NUTS levels for each EU member country (e. g. for Germany, NUTS 0 = country, NUTS 1 = federal states or “Bundesländer,” NUTS 2 = “Regierungsbezirke” [larger administrative regions], and NUTS 3 = districts or “Kreise”).

One could also argue that the level of analysis should be on the state level since university funding is determined by policies at the state level. However, as outlined in chapter 2.1 there is a regional dimension of university financing within states. That is, universities are based in different districts of a state and obtain their funding partly based on performance measures.

Only 12 (1.4%) out of all EXIST start-up grants were awarded to private universities. There was no stipend assigned to members of parochial universities. Besides, there have been 22 start-up grants awarded to research institutes which we did not consider because the university statistics includes no information on them.

A complete list of these universities can be obtained upon request.

This sample comprises also few universities with multiple locations across regions which are counted as separate entities due to the structure of the German university Statistics.

Some higher education institutions belonging to the universities of Arts and Culture like the Bauhaus University Weimar are among the most active universities with respect to start-up activities.

A correlation matrix is not shown for brevity but can be obtained upon request.

To this end, we regress population share on the respective population shares and predict the residual which is then used in our main regression analysis.

We also considered income per capita in alternative models. This variable is highly correlated with GDP per capita.

The change of funding conditions in 2015 (EXIST 2015) led to a delay of applications. Projects postponed their submission date from end of 2014 to the beginning of 2015. Therefore the number of projects in 2014 without the change of conditions would have been higher.

For 87 of the start-up grants it could not be assessed whether the project idea is related to demographic change or not. The reason is that our search for some of the projects was unsuccessful which indicates that the respective projects never ended up in a real firm.

Interestingly, there are no universities where there were projects with no demography related business ideas and project with such a business idea occurring in the same year. Thus, universities have either only DREPs in a certain year or only non-DREPs in a certain year (conditioned on that there was a start-up grant). So, technically one could also apply multinomial logit regressions. However, the mutually exclusive appearance of DREP and non-DREP grants in the data is accidentally.

Similar results can be obtained when using the population share of people above the age of 75 years. There is no relationship with DREPs and on average a negative marginal effect of 2.7% on the likelihood of an EXIST start-up grant in general and 2.4% for Non-DREP grants. Finally, we use the general development of population since German re-unification in 1990 as indicator for demographic change. Interestingly, there is only a weakly significant relationship between the change in population and university spin-off activities. The change in population reflects general migration and is therefore a less precise proxy for regional age structure and demographic change. The results can be obtained upon request.

One caveat is that the case number is reduced due to perfect predictions when considering 96 dummies for the planning regions. Therefore, we abstain from reporting these results. They can be provided upon request.

The interviews were part of the research project “RegDemo – Hochschulstrategien für Beiträge zur Regionalentwicklung unter Bedingungen demografischen Wandels – Die Rolle von Ausbildung, Forschung, Netzwerken und akademischen Gründungen.” RegDemo was funded from 2011 to 2014 by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant no. 01PW11011C.

Within the context of the research project RegDemo regional analyses were conducted on the level of planning regions (BBSR).

Interviews were conducted prior to the quantitative assessment. Therefore interviewees could not directly be asked about these DREP.

The software f4transkript was used for the transcription.

Hesse (2014, 2015) and Vorderwülbecke (2015) present in-depth analyses of supporting activities at the University of Göttingen and the University of Hannover. Both authors use survey data and semi structured interviews for their comparison. Their qualitative approaches are well documented. We refrain from presenting the answers in detail. We report our findings on answers which are connected to demographic change.

http://www.expertsight.com/de/ last accessed 26 August 2016.

https://www.pajubo.de/ accessed 26 August 2016.

http://www.medcooling.com/ accessed 26 August 2016.

https://www.jonnyfresh.de/ accessed 26 August 2016.

References

Astebro T, Bazzazian N (2011) Universities, entrepreneurship, and local economic development. In: Fritsch M (ed) Handbook of research on entrepreneurship and regional development: national and regional perspectives. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 252–334

Audretsch DB, Feldman MP (1996) R&D Spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. Am Econ Rev 86:630–640

Babb EM, Babb SV (1992) Psychological traits of rural entrepreneurs. J Socio Econ 21(4):353–362

Bauernschuster S, Falck O, Heblich S (2010) Social capital access and entrepreneurship. J Econ Behav Organ 76(3):821–833

Bergmann H, Hundt C, Sternberg R (2016) What makes student entrepreneurs? On the relevance (and irrelevance) of the university and the regional context for student start-ups. Small Bus Econ 47(1):53–76

Brunow S, Hirte G (2006) Age structure and regional economic growth. Rev Reg Res 26:3–23

Cameron CA, Trivedi P (2009) Microeconometrics using STATA. STATA Press Publication, College Station TX

Dahl M, Sorenson O (2012) Home sweet home: entrepreneurs’ location choices and the performance of their ventures. Manage Sci 58(6):1059–1071

Delfmann H, Koster S, McCann P, Van Dijk J (2014) Population change and new firm formation in urban and rural regions. Reg Stud 48(6):1034–1050

Dotti NF, Fratesi U, Lenzi C, Percoco M (2015) Local labour market conditions and the spatial mobility of science and technology university students: evidence from Italy. Rev Reg Res 34:119–137

Drakopoulou Dodd S, Hynes BC (2012) The impact of regional entrepreneurial contexts upon enterprise education. Entrep Reg Dev 24(9–10):741–766. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.566376

Easy Listen (2014) Easy listen. http://www.easy-listen.de/. Accessed 19 August 2016

Etzkowitz H (2003) Research groups as ‘quasi-firms’: The invention of the entrepreneurial university. Res Policy 32(1):109–121

EXIST (2015) EXIST. http://www.exist.de/. Accessed 19 August 2016

Feldman MP, Francis J (2003) Fortune favours the prepared region: The case of entrepreneurship and the Capitol region biotechnology cluster. Eur Plan Stud 11:765–788

Fini R, Grimaldi R, Santoni S, Sobrero M (2011) Complements or substitutes? The role of universities and local context in supporting the creation of academic spin-offs. Res Policy 40:1113–1127

Freire-Gibb LC, Nielsen K (2014) Entrepreneurship within urban and rural areas: creative people and social networks. Reg Stud 48(1):139–153

Fritsch M (2013) New business formation and regional development – a survey and assessment of the evidence. Found Trends Entrep 9:249–364

Fritsch M, Aamoucke R (2013) Regional public research, higher education, and innovative start-ups: an empirical investigation. Small Bus Econ 41(4):865–885

Fritsch M, Mueller P (2007) The persistence of regional new business formation activity over time: Assessing the potential of policy promotion programs. J Evol Econ 17(3):299–315

Fritsch M, Piontek M (2015) Die Hochschullandschaft im demografischen Wandel – Entwicklungstrends und Handlungsalternativen. Raumforsch Raumordn 73:357–368

Fritsch M, Pasternack P, Titze M (2015) Schrumpfende Regionen – dynamische Hochschulen. Hochschulstrategien im demografischen Wandel. SpringerVS, Berlin Heidelberg

Goethner M, Wyrwich M (2016) Proximity, cross-faculty spillovers, and the emergence of entrepreneurial ideas at universities, mimeo. Under review

Di Gregorio D, Shane S (2003) Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Res Policy 32:209–227

Gregory T, Patuelli R (2015) Demographic ageing and the polarization of regions – an exploratory space-time analysis. Environ Plan A 47(5):1192–1210

Gulbrandsen M, Smeby JC (2005) Industry funding and university professors’ research performance. Res Pol 34(6):932–950

Heblich S, Slavtchev V (2014) Parent universities and the location of academic startups. Small Bus Econ 42(1):1–15

Hesse N (2014) Academic entrepreneurs: attitudes, careers and growth intentions. Dissertation. Institut für Wirtschafts- und Kulturgeographie, Leibniz Universität, Hannover

Hesse N (2015) Career paths of academic entrepreneurs and university spin-off growth. In: Baptista R, Leitao J (eds) Entrepreneurship, human capital, and regional development. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 29–57

Jaeger A, Kopper J (2014) Third mission potential in higher education: measuring the regional focus of different types of HEIs. Rev Reg Res 34:95–118

Jayawarna D, Jones O, Macpherson A (2011) New business creation and regional development: enhancing resource acquisition in areas of social deprivation. Entrep Reg Dev 23(9–10):735–761. doi:10.1080/08985626.2010.520337

Kalar B, Antoncic B (2015) The entrepreneurial university, academic activities and technology and knowledge transfer in four European countries. Technovation 36:1–11

KMK (2014) Vorausberechnung der Studienanfängerzahlen 2014 – 2025: Erläuterung der Datenbasis und des Berechnungsverfahrens. Statistische Veröffentlichungen der Kultusministerkonferenz. Dokumentation Nr. 205

Kohlbacher F, Herstatt C, Leven N (2014) Golden opportunities for silver innovation: how demographic changes give rise to entrepreneurial opportunities to meet the needs of older people. Technovation 39:73–82

Krabel S, Mueller P (2009) What drives scientists to start their own company? An empirical investigation of Max Planck Society scientists. Res Policy 38:947–956

Lawton Smith H, Bagchi-Sen S (2012) The research university, entrepreneurship and regional development: research propositions and current evidence. Entrep Reg Dev 24(5–6):383–404. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.592547

Malecki EJ (2003) Digital development in rural areas: potentials and pitfalls. J Rural Stud 19(2):201–214

Michelacci C, Silva O (2007) Why so many local entrepreneurs? Rev Econ Stat 89(4):615–633

O’Shea RP, Allen TJ, Chevalier A, Roche F (2005) Entrepreneurial orientation, technology transfer and spinoff performance of U.S. Universities. Res Policy 34:994–1009

Powers JB, McDougall PP (2005) University start-up formation and technology licensing with firms that go public: a resource-based view of academic entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur 20:291–311

Ragnitz J (2009) Prospects for regional development and entrepreneurship in East Germany. In: Potter J, Hofer AR (eds) Strengthening entrepreneurship and economic development in East Germany: lessons from local approaches. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,, Paris, pp 13–27

Rahmenvereinbarung (2015) Rahmenvereinbarung IV zwischen der Thüringer Landesregierung und den Hochschulen des Landes. Thüringer Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Wissenschaft und Digitale Gesellschaft, Erfurt

Rothaermel FT, Agung SD, Jiang L (2007) University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Ind Corp Change 16(4):691–791

Segal NS (1986) Universities and technological entrepreneurship in Britain: some implications of the Cambridge phenomenon. Technovation 4:189–204

Shane S (2000) Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organ Sci 11(4):448–469

Smallbone D (2009) Fostering entrepreneurship in rural areas. In: Potter J, Hofer AR (eds) Strengthening entrepreneurship and economic development in East Germany: lessons from local approaches. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,, Paris, pp 161–187

Stam E (2007) Why butterflies don’t leave: locational behavior of entrepreneurial firms. Econ Geogr 83(1):27–50

Statistisches Bundesamt. various volumes. Hochschulstatistiken. Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden

Sternberg R (2014) Success factors of university-spin-offs: regional government support programs versus regional environment. Technovation 34:137–148

STIFT (2016) STIFT. https://www.stift-thueringen.de/. Accessed 26 August 2016

Vorderwülbecke A (2015) The Contribution of Alumni Spin-off Entrepreneurs to a University’s Entrepreneurial Support Structure – Conceptual Arguments, Empirical Evidence and Recommendations for an Effective Mobilization. Dissertation. Institut für Wirtschafts- und Kulturgeographie, Leibniz Universität, Hannover

Wagner J, Sternberg R (2004) Start-up activities, individual characteristics, and the regional milieu: lessons for entrepreneurship support policies from German micro data. Ann Reg Sci 38:219–240

ZLV (2016) Ziel- und Leistungsvereinbarung für die Jahre 2016 bis 2019 zwischen dem Thüringer Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Wissenschaft und Digitale Gesellschaft (TMWWDG) und der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena (FSU Jena). Thüringer Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Wissenschaft und Digitale Gesellschaft, Erfurt

Zucker LG, Darby MR, Brewer M (1998) Intellectual capital and the birth of U.S. biotechnology enterprises. Am Econ Rev 88:290–306

Zucker LG, Lyyne G, Darby MR, Armstrong JS (2002) Commercializing knowledge: university science, knowledge capture, and firm performance in biotechnology. Manag Sci 47:752–768

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An earlier version of this paper is based on a book chapter in German in Fritsch, M., Pasternack, P. & Titze, M. (2015). Schrumpfende Regionen – dynamische Hochschulen. Hochschulstrategien im demografischen Wandel. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer VS. The methodology and the dataset are significantly revised and extended. The submitted manuscript differs significantly from the aforementioned contribution.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Questionnaire

(1) Specific Part (Foundation)

(2–3) General Part (Analysis of the research- and transfer function of universities)

1.1.1 1. Encouragement of the entrepreneurial culture

Strategy of the university

Is there a clear commitment of your university towards the encouragement of entrepreneurial culture? Is this an important topic at your university?

(space for answering)

Check, if not already answered: Since when? Participation at the EXIST-Program?

What kind of resistance (i. e. administrative, with regard to content, technical) do you experience with respect to the encouragement of an entrepreneurial culture and the support of university spin-offs at your university?

(space for answering)

Activities to support university spin-offs

Are there staff members, who are only responsible to support spin-offs? If yes, how many? What kind of (professional) background do they have? What exactly are their tasks?

We maybe know this already (possible question: How many working hours do they have?)

(space for answering)

Which interdisciplinary activities are offered at your university to support spin-offs? (i. e. business-plan seminars, general information about entrepreneurship, elevator pitchs, summer schools)

(space for answering)

How many students participate at these (optional) activities with an entrepreneurship topic?

(space for answering)

How many persons make use of the coaching services at your university?

(We mean one to one consultation, i. e. consultation hour or appointments by arrangement)

(space for answering)

How deep are entrepreneurial courses integrated into the curriculum of each faculty? Is there a specific chair for Entrepreneurship professors? If yes, in which subjects?

(space for answering)

Incubator & Cooperation

Important tip: The following questions could already be answered!

Does your university have own institutions (i. e. so called university-incubator) or are there strong cooperation with technology- and start-up centers?

(space for answering)

How does this cooperation with local/regional technology- and start-up-centers look like? What is your opinion about the success of these centers?

(space for answering)

Are there well-established connections between financing institutions (i. e. banks, venture capital, Business Angels) and your university with the aim to support university spin-offs?

(space for answering)

Does your university cooperate with regional and/or national firms to encourage an entrepreneurial culture and mentoring university spin-offs? (i. e. coaching by patent attorneys, mentorship)

(space for answering)

Does your university cooperate with other universities to foster the own entrepreneurial culture?

(space for answering)

Do you have any ideas how the collaboration with local policy makers could be improved, to strengthen an entrepreneurial culture at your university and to directly support university spin-offs?

(space for answering)

How could the collaboration with regional interest groups be improved (i. e. Chamber of Commerce, financing institutions, promotion of economic development) to encourage the entrepreneurial culture at your university?

(space for answering)

What do you think; which potential can be exploited within the collaboration of (local) firms and your university to promote entrepreneurial culture?

(space for answering)

What is your opinion about the financial support of your federal state (Is there any? How satisfied are you?)

(space for answering)

Who are the most central actors in your local (university) start-up community for you?

(space for answering)

1.1.2 2. Extent of spin-off activities

For how many EXIST Business Start-Up Grants are applications filed and how many are successful?

(space for answering)

Which measures would increase the interest about entrepreneurship for the members of your university?

(space for answering)

How many university spin-offs did you have in the past?

(Tip: All spin-offs should be mentioned – not only those with EXIST grants)

(space for answering)

Can you estimate the share of students, staff, professors, alumni and teams involved in start-ups? Did this share varied over the past years?

(space for answering)

Which industries do your spin-offs typically enter?

(space for answering)

Where do they settle?

(space for answering)

Are there subjects at your university with unexpected high/low shares of spin-offs?

(space for answering)

To which extent can these spin-offs be seen as transfer of knowledge from the university? Please name examples.

Tip: we mean the transfer of research results and not the use of typical professional skills (i. e. management or leadership skills)

(space for answering)

If spin-offs rarely use research results as basis for their foundation, what could be the reasons and how could the knowledge transfer be improved?

(space for answering)

How does your university support spin-offs in this case (i. e. assignment of patents or licences)?

(space for answering)

Does your university keep contact to spin-offs after they left the university (alumni entrepreneurs)?

(space for answering)

Do alumni entrepreneurs keep in contact with the university?

(space for answering)

To which extent does your university later collaborate with spin-offs?

(space for answering)

Do you have an idea how spin-offs develop with respect to number of created jobs and the innovative performance?

(space for answering)

1.1.3 3. Promotion of university spin-offs and entrepreneurial culture in times of demographic change

Is the demographic change and the potential decline in the number of students considered in the planning of (future) tasks to promote university spin-offs?

(space for answering)

General part: research and technology.

Please consider the last five years. Which regional effects refer directly to the activities of the technology transfer office and would not have been realizable without it?

(space for answering)

-

a)

Are there aims and demands, which are linked to the implementation of the transfer office, but were not reached yet?

(space for answering)

-

b)

If yes, what do you think are the reasons?

(space for answering)

In how far does the demographic change influence the university’s strategy with respect to research and technology transfer?

(space for answering)

How does the demographic change challenge the transfer into the region?

(space for answering)

Which specific actions consider the demographic change?

(space for answering)

1.2 Definition of DREP

A start-up grant was counted as a DREP if there was a direct reference to the health care sector and demography in categories like “about us”; “profile”; “vision” describing the product and service portfolio at the webpage of the funded projects. Another criterion would be if the products and services aim directly at a growing market due to population aging. Examples for this category are the projects ExpertSight.Footnote 26 ExpertSight offers software and coaching for healthcare companies to forecast future developments especially the demographic change.

We also assigned business ideas to the DREP-category if demography is not explicitly mentioned by the project but if it is very likely that there will be a growing demand for the products and services offered when society is aging. This often applies to business ideas from the medical sector which is aiming at tackling age-related illnesses. Typical examples are pajuboFootnote 27 and MedCooling.Footnote 28 MedCooling distributes the “Cara Cooler” to initiate therapeutic hypothermia and pajubo is active within the field of dolefulness.

We also considered a third group of ideas whose products and services are particularly relevant for older people but could be also demanded by younger age groups. A typical example is Jonny FreshFootnote 29 with an online platform for a laundry connected to collect and bring service. Easy listen is a further example for the third group which we highlighted in more detail in the main part of the paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piontek, M., Wyrwich, M. The emergence of entrepreneurial ideas at universities in times of demographic change: evidence from Germany. Rev Reg Res 37, 1–37 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-016-0111-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-016-0111-6