Abstract

To make accurate assessments about their environment, animals must integrate a variety of sensory cues into a single unified percept. The effects of redundant multimodal signaling may be equivalent to the responses elicited by each individual cue, or enhanced when cues are combined. Binding of two seemingly coupled cues can persist despite small spatial and temporal discrepancies in signal presentation, a phenomenon termed the ventriloquist effect. Our study had two aims: first, to test the cognitive ability of a territorial, forest-dwelling bird to bind two spatially disparate cues; and second, to define the processing of the acoustic and visual cues as having either equivalent or enhanced effects when presented together. We broadcasted pied currawong (Strepera graculina) vocalizations alone or in the presence of a model currawong situated either adjacent to, or far away from a speaker, to free-living currawongs. The number of locomotive events and the average standard deviation in the distance from the speaker maintained by the focal currawong were greater in response to “far” than “close” treatments. Additionally, the average standard deviation of the distance to speaker for the uni-modal, speaker only treatment was similar to “far” responses. These findings support our hypothesis that currawongs cognitively bind two stimuli in close spatial proximity. In nature, this would result in an enhanced level of response toward territorial intruders. Our study was novel in its attempt to assess cognitive processes involved in the integration of spatially disparate bimodal signaling events in free-living birds.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alais D, Burr D (2004) The ventriloquist effect results from near-optimal bimodal integration. Curr Biol 14:257–262

Aydin A, Pearce JM (1997) Various determinants of response summation. Anim Learn Behav 25:108–121

Blumstein DT, Daniel JC, Evans CS (2006) JWatcher 1.0. http://www.jwatcher.ucla.edu

Chandler CR, Rose RK (1988) Comparative-analysis of the effects of visual and auditory stimuli on avian mobbing behavior. J Field Ornithol 59:269–277

Chantrey DF, Workman L (1984) Song and plumage effects on aggressive display by the European Robin Erithacus rubecula. Ibis 126:366–371

Charif RA, Mitchell S, Clark CW (1995) Canary 1.12 user’s manual. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca

Cherry EC (1953) Some experiments on the recognition of speech, with one and two ears. J Acoust Soc Am 25:975–979

Cohen DJ (1997) Visual detection and perceptual independence: assessing color and form. Percep Psychophys 59:623–635

Hankison SJ, Morris MR (2003) Avoiding a compromise between sexual selection and species recognition: female swordtail fish assess multiple species-specific cues. Behav Ecol 14:282–287

Horton H (2000) Australian birdsong collection. Australian Broadcasting Service, Sydney

Hoy R (2005) Animal awareness: the unbinding of multi-sensory cues in decision making by animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2267–2268

Jack CE, Thurlow WR (1973) Effects of degree of visual association and angle of displacement on ventriloquism effect. Percept Motor Skill 37:967–979

Knight RL, Temple SA (1986) Nest-defense in the American goldfinch. Anim Behav 34:887–897

Marler P, Tenaza R (1977) Signaling behavior of apes with special reference to vocalization. In: Sebeok TA (ed) How animals communicate. Indiana University Press, Ontario, pp 965–1033

Martin P, Bateson P (1986) Measuring behavior: an introductory guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mathevon N, Aubin T (1997) Reaction to conspecific degraded song by the wren Troglodytes troglodytes: territorial response and choice of song post. Behav Process 39:77–84

McGurk H, MacDonald J (1976) Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature 264:746–748

Movellan JR, McClelland JL (2001) The Morton-Massaro law of information integration: implications for models of perception. Psych Rev 108:113–148

Moulton CE, Brady RS, Belthoff JR (2004) Territory defense of nesting burrowing owls: responses to simulated conspecific intrusion. J Field Ornithol 75:288–295

Naguib M (1996) Auditory distance estimation in song birds: implications, methodologies and perspectives. Behav Process 38:163–168

Naguib M, Amrhein V, Kunc HP (2004) Effects of territorial intrusions on eavesdropping neighbors: communication networks in nightingales. Behav Ecol 15:1011–1015

Naguib M, Wiley RH (2001) Estimating the distance to a source of sound: mechanisms and adaptations for long-range communication. Anim Behav 62:825–837

Narins PM, Hodl W, Grabul DS (2003) Bimodal signal requisite for agonistic behavior in a dart-poison frog, Epipedobates femoralis. P Natl Acad Sci USA 100:577–580

Narins PM, Grabul DS, Soma KK, Gaucher P, Hodl W (2005) Cross-modal integration in a dart-poison frog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2425–2429

Nowicki S, Searcy WA, Krueger T, Hughes M (2002) Individual variation in response to simulated territorial challenge among territory-holding song sparrows. J Avian Biol 33:253–259

Partan S, Yelda S, Price V, Shimizu T (2005) Female pigeons, Columba livia, respond to multisensory audio/video playbacks of male courtship behaviour. Anim Behav 70:957–966

Partan SR, Marler P (2005) Issues in the classification of multimodal communication signals. Am Nat 166:231–245

Recher HF (1976) Reproductive behaviour of a pair of pied currawongs. Emu 76:224–226

Rovner JS, Barth FG (1981) Vibratory communication through living plants by a tropical wandering spider. Science 214:464–466

Rowe C (1999) Receiver psychology and the evolution of the multicomponent signals. Anim Behav 58:921–931

Rowe C, Guilford T (1999) Novelty effects in a multimodal warning signal. Anim Behav 57:341–346

Shalter MD (1978) Mobbing in the pied flycatcher effect of experiencing a live owl on responses to a stuffed facsimile. Z Tierpsychol 47:173–179

Slutsky DA, Recanzone GH (2001) Temporal and spatial dependency of the ventriloquism effect. Neuroreport 12:7–10

Spence C, Driver J (2004) Introductory comments. In: Spence C, Driver J (eds) Crossmodal space and crossmodal attention. Oxford University Press, New York, pp v–ix

SPSS, Inc. (2002) SPSS 11 for the Macintosh. SPSS Inc., Chicago

Stein BE, Stanford TR, Wallace MT, Vaughan JW, Jiang W (2004) Crossmodal spatial interaction in subcortical and cortical circuits. In: Spence C, Driver J (eds) Crossmodal space and crossmodal attention. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 25–50

Thurlow WR, Jack CE (1973) Certain determinants of ventriloquism effect. Percept Motor Skill 36:1171–1184

Wells KD (1978) Territoriality in the green frog (Rana clamitans): vocalizations and agnostic behavior. Anim Behav 26:1051–1063

van der Veer IT (2002) Seeing is believing: information about predators influences yellowhammer behaviour. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 51:466–471

Acknowledgments

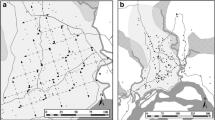

For permission to work in Booderee National Park, we thank the National Park staff and the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community. Additionally, we thank Tony Davidson for permission to work on the H.M.A.S. Creswell. We thank the UCLA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, the Lida Scott Brown Ornithology Trust, and the UCLA Office of Instructional Development for their generous support, and Peter Narins, Tatiana Czeschlik, and four particularly constructive reviewers for comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lombardo, S.R., Mackey, E., Tang, L. et al. Multimodal communication and spatial binding in pied currawongs (Strepera graculina). Anim Cogn 11, 675–682 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-008-0158-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-008-0158-z