Abstract

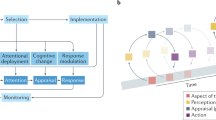

REBT theoreticians and practitioners describe two sets of emotions (and behaviors) as a reaction to adversity, whether these are functional or dysfunctional. This article deals with the ways in which REBT practitioners and theoreticians interpret these two sets of reactions, using either a quantitative or qualitative method. It favors the qualitative approach and illustrates it with a graphical representation of the two sets. The use of graphs turns out to be particularly useful for explaining certain phenomena to clients and for teaching novice practitioners. It also provides a framework for establishing an effective new thought or rational belief.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Backx, W. (2000). The Tuesday night workshop. Video demonstration of a REBT session by Albert Ellis. Haarlem: Instituut voor RET (in press).

Backx, W. (2003). REBT as an intentional therapy. In W. Dryden (Ed.), Rational emotive behavioural therapy: Theoretical developments. Hove, East Sussex and New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

Brewin, C. R., Dalgleish, T., & Joseph, S. (1996). A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review, 103, 670–686.

Cornelius, R. R. (1996). The science of emotion. Research and tradition in the psychology of emotion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

David, D., Montgomery, G. H., Macavei, b., & Bovbjerg, D. H. (2005). An emperical investigation of Albert Ellis’ binary model of distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 499–516.

David, D., Schnur, J., & Belloiu, A. (2002). Another search for the “hot” cognitions: Appraisal, irrational beliefs, attributions, and their relation to emotion. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 15, 93–131.

David, D., Schnur, J., & Birk, J. (2004). Functional and dysfunctional feelings in Ellis’cognitive theory of emotion: An empirical analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 18, 869–880.

DiLorenzo, T. A., Bovbjerg, D. H., Montgomery, G. H., Jacobsen, P. B., & Vladimarsdottir, H. (1999). The application of a shortened version of the profile of mood states in a sample of breast cancer chemotherapy patients. British Journal of Health Psychology, 4, 315–325.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. Secaucus NJ: Lyle Stuart.

Ellis, A. (1988). How to stubbornly refuse to make yourself miserable about anything. Yes anything. Secaucus NJ: Lyle Stuart.

Ellis, A., & DiGiuseppe, R. (1993). Are inappropriate or dysfunctional feelings in rational-emotive therapy qualitative or quantitative? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 5, 471–477.

Ellis, A., & Grieger, R. (1977). Handbook of rational-emotive therapy. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., & Walser, R. D. (2007). Learning ACT: An acceptance & commitment therapy skills-training manual for therapists. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Parrot, W. G. (2001). Implications of dysfunctional emotions for understanding how emotions function. Review of General Psychology, 5, 180–186.

Walen, S., DiGiuseppe, R., & Dryden, W. (1992). A practitioner’s guide to RET (2nd ed.). New York, Oxford: University Press.

Walen, S., DiGiuseppe, R., & Wessler, R. (1980). A practitioner’s guide to RET. New York, Oxford: University Press.

Wessler, R. A., & Wessler, R. L. (1980). The principles and practice of rational-emotive therapy. San Francisco, Washington, London: Jossey-Bass.

Wolpe, J. (1973). The practice of behavior therapy. New York: Pergamon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Backx, W. The Distinction Between Quantitative and Qualitative Dimensions of Emotions: Clinical Implications. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 30, 25–37 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-010-0122-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-010-0122-0