Abstract

There is strong evidence that early pubertal timing is associated with adolescent problem behaviors. However, there has been limited investigation of the mechanisms or developmental relationships. The present study examined longitudinal models incorporating pubertal timing, delinquency, and sexual activity in a sample of 454 adolescents (9–13 years old at enrollment; 47% females). Participants were seen for three assessments approximately 1 year apart. Characteristics of friendship networks (older friends, male friends, older male friends) were examined as mediators. Structural equation modeling was used to test these associations as well as temporal relationships between sexual activity and delinquency. Results showed that early pubertal timing at Time 1 was related to more sexual activity at Time 2, which was related to higher delinquency at Time 3, a trend mediation effect. None of the friendship variables mediated these associations. Gender or maltreatment status did not moderate the meditational pathways. The results also supported the temporal sequence of sexual activity preceding increases in delinquency. These findings reveal that early maturing adolescents may actively seek out opportunities to engage in sexual activity which appears to be risk for subsequent delinquency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is substantial evidence that early pubertal maturation is associated with problem behaviors such as early sexual activity, delinquency, bullying, truancy, disruptive behavior, and violent behavior (Flannery et al. 1993; Graber et al. 1997; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2003; Obeidallah et al. 2004). Early maturing girls have been found to have the highest levels of delinquency, both cross-sectionally and across time (Caspi et al. 1993; Haynie 2003). However, in one study, at age 15 on-time maturing girls were found to have the same levels of delinquency as earlier maturing girls, both of whom exhibited more delinquency than later maturing girls (Caspi et al. 1993). In studies with all male samples, one study found early maturation to be associated with higher levels of violent and non-violent delinquency (Cota-Robles et al. 2002), whereas another found both early and late timing were associated with the highest levels of delinquent behavior (Williams and Dunlop 1999). Overall, the evidence demonstrates a strong link between pubertal timing and delinquency.

A number of studies have also shown sexual activity to be associated with pubertal timing. For example, early maturing White and Latina girls were found to be at increased risk for early sexual debut, but African American girls were not (Cavanagh 2004). Results from studies that included both genders found sexual activity, bullying, truancy, and delinquency to be higher in both early maturing boys and girls compared to on-time or late maturing individuals (Flannery et al. 1993; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2003; Miller et al. 1998). However, Crockett et al. (1996) did not find an association between early pubertal timing and sexual initiation for males or females after controlling for other relevant factors such as family risk, substance use, and delinquency. Finally, it has been reported that there is an association between early maturation and sexual activity for males but not females (Rosenthal et al. 1999). The inconsistent findings have not been helpful in sorting out the specific longitudinal pathways between timing of puberty and delinquency or between timing of puberty and sexual activity. A source of the inconsistency may be in the measures of pubertal timing used across studies. Research shows that the strength of associations may vary based on the method used to classify pubertal timing (Negriff et al. 2008). Despite the number of studies on puberty and problem behaviors, there is little evidence regarding the longitudinal pathways between timing of puberty, delinquency and sexual activity or the mechanisms that link pubertal timing to these risk behaviors.

Mediators: Peer Influence for Early Maturers

One theory about the mechanism linking early pubertal timing and problem behaviors in girls proposes that early development leads to delinquent behaviors or early sexual activity because early maturing adolescents are influenced by the gender and/or age composition (e.g. older males) and problem behaviors of their peer group (Stattin and Magnusson 1990). Evidence indicates that exposure to deviant, older, or male peers is particularly harmful for girls (Caspi et al. 1993; Haynie 2003). Early maturing adolescents may be accepted into older peer groups based on their advanced physical maturity and engage in delinquent or sexual behaviors that are relatively normative for older adolescents but inappropriate for younger individuals such as themselves. Thus, early maturers may be drawn into delinquency or sexual activity by their older peers based on their physical characteristics but may not have the capacity cope with peer pressure as effectively as later maturing adolescents because of their relatively immature emotional and cognitive development (Simmons and Blyth 1987; Stattin and Magnusson 1990).

Several studies support the notion that deviant peers mediate the association between pubertal timing and sexual activity and delinquency, although the evidence is primarily for girls. In a sample of girls from mixed gender schools, familiarity with delinquent peers mediated the relationship between earlier age at menarche and norm-violating behaviors for girls without a childhood history of externalizing problems (Caspi et al. 1993). Similarly, Haynie (2003) found that exposure to peer deviance and involvement in romantic relationships mediated the relationship between early pubertal development and delinquent behaviors. Lastly, early maturing White and Latina girls were found to have more older boys in their friendship groups, more friends who engaged in problem behaviors, and were more likely to have engaged in early sexual behavior than on-time or late maturers (Cavanagh 2004). In addition, having a higher number of friends was found to partially mediate the association between early puberty and sexual debut for White girls. Although peer influence appears to be a likely mediator for females, there are only a few studies that have examined this association for males as well.

Two studies have examined peer delinquency as a mediator for both males and females. In the first study, peer delinquency in 6th grade mediated the relationship between early pubertal timing in 6th grade and delinquency in 6th, 7th, and 8th grades (Lynne et al. 2007). Similarly, in a longitudinal study with 454 boys and girls Negriff et al. (in press) reported that exposure to peer delinquency mediated the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency 3 years later, and this mediational relationship held for both males and females. Although there is support for the detrimental effect of deviant peers on delinquency, there is scant evidence as to whether it is specifically older age, older male, or simply male peers that drive this effect. It is assumed that early maturing adolescents, particularly females, are seen by older males as more physically mature, and therefore are drawn into associations with them. Older males are more likely to exhibit antisocial behavior and be sexually active themselves, thus exposing early maturers to opportunities for engaging in delinquent and sexual behaviors. Early maturing adolescents may not have the self regulatory skills to make good decisions about whether to engage in delinquency and sexual activity. Determining the specific peer group characteristics that are detrimental for early maturers will be important in understanding the developmental risks for early delinquency and sexual activity.

Mediators: Hormonal Processes

Another possible explanation is that internal hormonal processes associated with pubertal maturation may increase sexual desire and interest in the opposite gender (Flannery et al. 1993). Androgenic hormones, which increase during puberty, are a known concomitant of sexual motivation (Halpern et al. 1993, 1997; Persky et al. 1982; Udry 1988a). What has not been considered is that androgenic hormones, testosterone, in particular, may increase sexual desires resulting in early maturers seeking out sexual partners. In the only known randomized clinical trial of testosterone or estrogen administration, delayed puberty boys and girls reported an increase in sexual behavior and thoughts, respectively, at medium or high doses of testosterone or estrogen (Finkelstein et al. 1998). Additionally, Brown et al. (2005) found that earlier maturing females reported more sexual motivation (e.g. interest in seeing sexual content in movies, television, and magazines), were more likely to actually be listening to music and reading magazines with sexual content, and were more likely to interpret media as being approving of teen sex. This evidence demonstrates that early pubertal maturation and sexual motivation seem to be linked.

Models proposed by Brooks-Gunn and colleagues (Brooks-Gunn et al. 1994) to explain associations between puberty and negative affect also can be applied to sexual activity and delinquency. Specifically, they propose that hormonal processes underlying the physical manifestations of puberty are actually responsible for changes in behavior, but these associations are moderated by social events or perceptions of puberty. When applied to sexual activity, the Brooks-Gunn model would indicate that hormonal changes lead to the development of secondary sexual characteristics, which are observable to peers, and prompt sexual interest in the adolescent and attract potential partners. Thus, early maturing adolescents may be active but unprepared participants in the selection of peers who may increase their risk for delinquency and sexual behavior.

The Developmental Associations Between Delinquency and Sexual Activity

The co-occurrence of delinquency and sexual activity has often been attributed to a syndrome of problem behavior that violates social norms regarding appropriate adolescent behavior (Jessor 1991). This theory proposes that many norm-violating behaviors cluster together because they evidence an underlying construct of “risk behavior”. A number of studies have documented this association between delinquency and sexual activity (Armour and Haynie 2007; Caminis et al. 2007; Devine et al. 1993), but there is little investigation into the possible temporal sequence. In relation to puberty, it may be that hormonal changes pique interest in sexual activity (Finkelstein et al. 1998), which drives adolescents to find potential sexual partners. Sexual partners may be older adolescents who are already sexually active as well as more likely to be delinquent, which then introduces early maturers to delinquent behavior.

Cross-sectional studies show a substantial correlation between sexual activity and delinquency for both males and females (Devine et al. 1993). Data from longitudinal studies indicate that early sexual activity is a risk for delinquency 1 year later (Armour and Haynie 2007), whereas other studies report that violent delinquency over the course of middle school is associated with higher sexual initiation rates during middle school (Caminis et al. 2007), or that early childhood externalizing problems predict later sexual activity via preadolescent behavior problems (Schofield et al. 2008). Additionally, externalizing behavior at age 9 predicted high-risk sexual behavior at age 16 (Siebenbruner et al. 2007). The National Youth Survey found that more males and females reported delinquency before the onset of sexual activity than after (Elliott and Morse 1989), providing evidence for the temporal sequence of delinquency preceding sexual activity. A four-wave study of high school sophomores found higher levels of delinquency associated with the earlier onset and persistence of intercourse activity (Tubman et al. 1996). Additionally, the authors found that the transition to the onset of sexual intercourse was associated with a greater acceleration of delinquent behaviors. Overall, the majority of studies support a correlation between delinquency and sexual activity, but there is still ambiguity as to whether delinquency precedes sexual activity or vice versa. In particular, no studies have examined the longitudinal pathways between pubertal timing, sexual activity, and delinquency to tease apart the temporal sequence as well as possible reciprocal relationships.

Moderators: Gender and Maltreatment Status

The research on pubertal timing and various problem behaviors has primarily been conducted with samples of adolescent females because puberty is easier to measure for females and early research presumed that puberty was more detrimental for females. This attention to females has left a gap in our understanding of these effects for males. In addition, mediational models have primarily been examined with females, although previous analyses have shown that deviant peers mediate the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency for both males and females (Lynne et al. 2007; Negriff et al., in press). However, there is a dearth of literature examining gender differences in the longitudinal relationships between pubertal timing, friendship composition, sexual activity, and delinquency.

Maltreatment is another potential moderator of these longitudinal associations. Individually, maltreatment is linked to poor interpersonal interactions, earlier onset of sexual activity, and increased delinquency (Anthonysamy and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007; Noll et al. 2003; Zingraff et al. 1993). What is not known is how the mediational relationships may vary based on maltreatment experience. Findings show that the expected developmental mechanisms may differ in maltreated adolescents; specifically, delinquent peers do not increase the delinquency of maltreated early maturers as they do for comparison adolescents (Negriff et al., in press). Thus, perhaps the trauma of maltreatment itself is more influential in the development of sexual behavior and delinquency than exposure to risky peers.

The Current Study

The purpose of this study was to test hypotheses regarding the temporal sequence of pubertal timing, characteristics of friends, delinquency, and sexual activity to examine mediational relationships across time. Two competing hypotheses were tested. First, it was hypothesized that early pubertal timing would be associated with risky friendship networks (same age male friends, older friends, or older male friends) that in turn would increase subsequent sexual activity and delinquency. Alternatively, it was hypothesized that early pubertal timing would be associated with increased sexual activity, then subsequently risky friends and delinquency. In the first model, risky friends were expected to mediate the relationship between early pubertal timing and both delinquency and sexual activity. In the second model, sexual activity was expected to mediate the association between early pubertal timing and risky friends and subsequent delinquency. In addition, gender and maltreatment were examined as moderators of these associations.

Research Design and Methods

Participants

The present study used data from the first three assessments (approximately 1 year apart) of an ongoing longitudinal study examining the effects of maltreatment on adolescent development. At Time 1, the sample was comprised of 454 adolescents aged 9–13 years (241 males and 213 females) and took place from 2002 to 2005.

Recruitment

The participants who comprised the maltreatment group (n = 303) were recruited from active cases in the Children and Family Services (CFS) of a large west coast city. The inclusion criteria were: (1) a new substantiated referral to CFS in the preceding month for any type of maltreatment (e.g. neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse); (2) child age of 9–12 years; (3) child identified as Latino, African-American, or Caucasian (non-Latino); (4) child residing in one of 10 zip codes in a designated county at the time of referral to CFS. With the approval of CFS and the Institutional Review Board of the affiliated university, potential participants were contacted via postcard and asked to indicate their willingness to participate. Contact via mail was followed up by a phone call.

According to information abstracted from the CFS case records, most children in the maltreated group experienced multiple forms of maltreatment and had multiple referrals as well [see Mennen et al. (2010) for details of the record abstraction]. The majority of the maltreatment sample experienced neglect in some form, about half of the sample experienced physical abuse and/or emotional abuse, and approximately one-fifth experienced sexual abuse. On average, the participants had experienced two types of maltreatment and four referrals to CFS.

The comparison group (n = 151) was recruited using names from school lists of children aged 9–12 years residing in the same 10 zip codes as the maltreated sample. Caretakers of potential participants were sent a postcard and asked to indicate their interest in participating which was followed up by a phone call.

Upon enrollment in the study, the maltreatment and comparison groups were compared on a number of demographic variables. The two groups were similar on age (M = 10.93 years, SD = 1.16), gender (53% male), race (38% African American, 39% Latino, 12% Biracial, and 11% Caucasian), and neighborhood characteristics (based on Census block information). However, they were different in terms of living arrangements. In the comparison group 93% lived with a biological parent, whereas this was the case for only 52% of the maltreatment group. The remainder of the maltreatment group was living in foster care, which is not unusual for those adolescents involved with social services.

Attrition

The attrition rate between Time 1 and Time 2 was 13.4% (n = 61) and between Time 1 and Time 3 in this study was 31% (n = 141). Two separate binary logistic regression analyses were performed to test whether attrition at Time 2 and Time 3 was random. The dependent variable for the attrition analysis was a dichotomous variable (yes/no) indicating attrition at Time 2 and Time 3. Time 1 pubertal timing variables, peer- and self-delinquency variables, sexual activity, and demographic variables were entered in order to predict the dropout of participants during the longitudinal assessment. The results of attrition analyses indicated that the participants who were not seen at Time 2 were more likely to be in the maltreatment group (OR = 4.38, p < .01; Nagelkerke’s R 2 = .10) and those not seen at Time 3 were more likely to be Latino (OR = 3.37, p < .01) and in the maltreatment group (OR = 5.36, p < .01; Nagelkerke’s R 2 = .19).

Procedures

Assessments were conducted at an urban research university. After assent and consent were obtained from the adolescent and caretaker, respectively, the adolescent was administered questionnaires and tasks during a 4-hour protocol. The measures used in the following analyses represent a subset of the questionnaires administered during the protocol, which also included hormonal, cognitive, and behavioral measures. Both the child and caretaker were paid for their participation according to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Normal Volunteer Program.

Measures

Pubertal Development

Tanner Stages. Pubertal stage was measured using the adolescent’s self-report on his/her stage of pubertal development using Tanner criteria (Marshall and Tanner 1969, 1970). Five stages of pubertal development are represented by sets of serial line drawings that depict the development of two different secondary sexual characteristics from prepubertal (stage = 1) to postpubertal (stage = 5) (Morris and Udry 1980). Female drawings are of breast development and pubic hair growth; male drawings are of genital development and pubic hair growth. Self-report on Tanner stages is highly correlated with physician assessment and sufficient when approximate estimation of pubertal stage is adequate (Dorn et al. 1990). Scores on each drawing (breast/genital and pubic hair) were used as separate indicators of pubertal development.

Pubertal Development Scale. The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) is a measure of the physical changes associated with pubertal development. It was developed as an alternative to physician rating measures and has shown to have adequate reliability and validity (Petersen et al. 1988). On a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (has not yet started) to 4 (has completed), each subject is asked to indicate the level of development on each of the physical changes. Five items were used for both males and females (height spurt, body hair, skin changes, breast growth/deepening of voice, menarche/facial hair; α = .61 for males, α = .76 for females). A coding system developed by Shirtcliff and colleagues (Shirtcliff et al. 2009) was used to convert the PDS scores to a 5-point scale to parallel the Tanner stages.

Pubertal Timing

When the degree of physical development is standardized within same-age peers, the resulting score can be used as an index of pubertal timing (Ge et al. 2001). For the present study, the scores on each of the Time 1 Tanner stage ratings (breast/genital and pubic hair) and the PDS scores were standardized within each age cohort (e.g. 9, 10, 11) and gender. The resulting z-score for the three measures had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 with higher scores indicating earlier maturation relative to peers.

Delinquency

The participants reported on their own delinquent behaviors within the past 12 months via 23 items from the Adolescent Delinquency Questionnaire [ADQ; adapted from Huizinga and Elliott (1986)]. Computerized administration was used to ensure participants’ confidentiality. For the present study, three scales were used: status offenses (6 items, e.g. “run away from home”, α = .74, .72, .68), person offenses (7 items, e.g. “carried a hidden weapon”, α = .83, .77, .75), and property offenses (10 items, e.g. “damaged or destroyed someone else’s property on purpose”, α = .92, .88, .84). Alphas refer to Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3, respectively. The items on each factor were summed to yield a composite score for that scale.

Friendship Network

The Child Social Support Questionnaire (Bogat et al. 1985) was used to measure aspects of the friendship network. The number of older friends was computed by summing all the friends more than 2 years older than the adolescent. The number of same age (within 2 years) male friends and older male friends were summed similarly.

Sexual Activity

Sexual activity was measured using the Sexual Activity Questionnaire for Girls and Boys (Udry 1988b). This questionnaire assesses a series of eleven sexual activities the adolescent may have engaged in with a current boyfriend/girlfriend, a past partner, or anyone. Activities begin with holding hands, continue with kissing, heavy petting, and culminate in sexual intercourse. The assumption is that if an adolescent has not done one of the introductory activities they will not have engaged in the more advanced ones. Thus, if they answer “no” to kissing they skip out of the rest of the questions. The eleven sexual activity items were summed (no = 0, yes = 1) to create a composite score of sexual activity with higher scores indicating more advanced sexual activity.

Data Analysis

Normality and Transformation of Data

In structural equation modeling (SEM), multivariate normality is a key assumption for maximum likelihood estimation (ML). Test statistics and standard errors based on ML can be biased under severe non-normality, which tends to inflate the chi-square statistics and to deflate some model fit indices such as the comparative fit index. The distributions of the delinquency scales indicated that these variables were positively skewed, which is common in non-clinical populations because few participants engage in delinquent behaviors. The variables were transformed using a square-root transformation method.

Missing Data

For the delinquency scales, some cases contained item-level missingness (a particular question on the scale was not answered) and thus a sum score could not be calculated. In order to obtain the maximum number of cases and to calculate the sum scores of the delinquency variables, item-level missing data were imputed using a multiple imputation method (Rubin 1987) with the NORM software program (Schafer 1999). Multiple imputation replaces missing data with an estimated value “representing a distribution of possibilities” through iteration processes. This resulted in 443 complete cases for Time 1, 391 for Time 2, and 300 for Time 3 for the delinquency scales. As with most prospective longitudinal studies, data for some participants was not available for all three times of assessment. Analyzing only those cases with complete data has the potential to produce biased results; therefore, the total sample was used for analyses (Muthén et al. 1987). Thus, Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation method (FIML) (Arbuckle 1996) was employed to handle variable level missingness and longitudinal missingness across time. This procedure does not impute data but breaks down the likelihood function into components based on patterns of missing data, allowing estimation to proceed using all available data.

Substantive Analyses/Hypothesis Testing

Structural equation models were used to test the hypotheses using Amos 18.0 (Arbuckle 2007). Latent variables were constructed for pubertal timing (with three manifest indicators: Tanner breast/genital, Tanner pubic hair, and PDS) and delinquency (with three manifest indicators: status, person, and property offenses). The three friendship variables (number of same age male friends, number of older friends, and number of older male friends) were included in three separate models as manifest variables. Pubertal timing was only included at Time 1, friend variables were included at Time 1 and Time 2 (because they were conceptualized as mediators), and delinquency and sexual activity were included at Time 1, 2, and 3. A cross-lagged model was tested, which included direct effects from all Time 1 variables to all Time 2 variables as well as covariances between disturbance terms within time and autoregressive effects across time. Covariates in the model were age at Time 1, gender, race (minority, non-minority), total number of friends, and maltreatment status (maltreated, comparison). Fit indices, such as the χ 2 (chi-square) goodness-of-fit statistic, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and comparative fit index (CFI), were used to evaluate the fit of the model to the data. Overall, a good model fit is indicated by a small χ 2, RMSEA of .08 or smaller, and CFI above .90 (Browne and Cudeck 1993; Shapiro and Levendosky 1999).

The models were first tested with the total sample and then multiple group models were used to test gender and maltreatment status as moderators. The one degree of freedom nested chi square difference test was used to determine if any parameters in the model were significantly different between groups.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviation, ranges of all study variables can be found in Table 1. Intercorrelations were computed between the variables of interest (Table 2). Significant correlations were found among all the pubertal timing variables for Time 1 (rs = .34–.63, p < .01). The three self-delinquency scales were found to have significant intercorrelations for Time 1 (rs = .74–.81, p < .01), Time 2 data (rs = .57–.73, p < .01) and Time 3 (rs = .61–.72, p < .01).

Mean differences by gender and maltreatment status were tested using an independent samples t-test. At Time 1, males had significantly more male friends and older male friends whereas at Time 2, the only group difference was that males had more male friends (see Table 2). Males scored significantly higher than females on sexual activity at all three time points. For the delinquency scales, males scored higher than females only for person offences at Time 1 and Time 2. Maltreated adolescents reported more status offenses and higher sexual activity at Time 1, whereas comparison adolescents had more older friends and older male friends at Time 1 and more male friends at Time 2.

Substantive Analyses

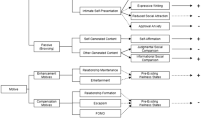

Number of Older Friends

The full model with the total sample fit the data adequately (χ 2 = 493.09 (189); CFI = .91; RMSEA = .06). As shown in Fig. 1, there were significant associations between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 number of older friends and between pubertal timing and Time 2 sexual activity. Earlier pubertal timing was related to having more older friends, but having more older friends was related to lower sexual activity at Time 3. However, this was not a significant mediation effect. There were also significant associations between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 sexual activity, as well as between Time 2 sexual activity and Time 3 delinquency. This was a trend mediation effect as indicated by Sobel’s test (z = 1.88, p = .059). There was also a significant indirect effect of Time 1 sexual activity on Time 3 sexual activity through Time 2 delinquency (z = 2.30, p = .025). These results indicate that older friends do not mediate the relationship between earlier timing of puberty and subsequent sexual activity and delinquency. It appears that early pubertal timing in itself increases sexual activity that in turn predicts higher delinquency.

Longitudinal relationships between pubertal timing, older friends, sexual activity and delinquency. All parameter estimates are standardized. Covariates (not shown) are T1 age, race, sex, total number of friends, and maltreatment status. Bold paths show significant mediation effects at p = .058 (pub → sex → delinq) and p = .02 (sex → delinq → sex)

Multiple Group Models. This model was then fit simultaneously to males and females. First, all measurement and structural parameters were unrestricted, then the measurement loadings were restricted to be equal across groups, then the structural weights were restricted across groups. The measurement weights restricted model did not differ significantly from the unrestricted model (Δχ2 = .39 (6), ns). Each structural parameter was tested in turn and only the parameter between Time 2 older friends and Time 3 delinquency was significantly different between groups (Δχ2 = 13.51 (1), p < .01). For males the parameter was positive and significant (B = .23, SE = .09, p < .01) whereas for females it was negative and significant (B = −.25, SE = .10, p < .05). Having more older friends was related to higher delinquency in males but lower delinquency in females.

Next, the model was fit to the maltreatment and comparison groups. As in the previous multiple group analysis, first the model was run with all measurement and structural parameters unrestricted, then the measurement loadings were restricted to be equal across groups, then the structural weights were restricted. The measurement weights restricted model did not differ significantly from the unrestricted model (Δχ 2 = 6.61 (4), ns). Each structural parameter was tested in turn and the results showed a moderating effect of maltreatment group on the parameter between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 older friends (Δχ 2 = 8.55 (1), p < .01). For the comparison group the parameter was positive and significant (B = .43, SE = .12, p < .01), whereas for the maltreated group it was not significant (B = .02, SE = .08, ns). This indicates that for comparison adolescents, early pubertal timing is related to having more older friends, whereas this association is not present for maltreated adolescents.

Number of Male Friends

The full model with the total sample fit the data poorly (χ 2 = 904.31 (189); CFI = .83; RMSEA = .09). There were no significant associations between number of male friends and any of the primary variables of interest. In addition, none of the parameters were moderated by gender or maltreatment status.

Number of Older Male Friends

The full model with the total sample fit the data adequately (χ 2 = 493.09 (189); CFI = .91; RMSEA = .06). Similar to the model with older friends, there were significant associations between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 sexual activity and between Time 2 sexual activity to Time 3 delinquency. This was a trend mediation effect as indicated by Sobel’s test (z = 1.88, p = .059). There was also a significant indirect effect of Time 1 sexual activity on Time 3 sexual activity through Time 2 delinquency (z = 2.30, p = .025). Unique to this model, there was a significant effect of Time 1 older male friends on Time 2 sexual activity (see Fig. 2). The direction of this coefficient indicated that having more older male friends at Time 1 increased sexual activity at Time 2. Sexual activity at Time 2 was related to Time 3 delinquency, but the indirect effect from Time 1 older friends to Time 3 delinquency (through Time 2 sexual activity) was not significant.

Longitudinal relations between pubertal timing, older male friends, sexual activity, and delinquency. All parameter estimates are standardized. Covariates (not shown) are T1 age, race, sex, total number of friends, and maltreatment status. Bold paths show significant mediation effects at p = .058 (pub → sex → delinq) and p = .02 (sex → delinq → sex)

Multiple Group Models. Next, the model was tested for moderation by gender as described previously. The measurement weights restricted model did not differ significantly from the unrestricted model (Δχ2 = 6.75 (6), ns). Subsequently, each parameter was tested in turn to determine if any were significantly different between males and females. The parameter from Time 2 older male friends to Time 3 delinquency was moderated by gender (Δχ2 = 13.94 (1), p < .01). The coefficient was positive and significant for males (B = .51, SE = .16, p < .01) and non-significant for females. Having older male friends predicted more delinquency in males but not females.

The model was then tested for moderation by maltreatment status. The measurement weights restricted model did not differ from the unrestricted model (Δχ 2 = 6.45 (4), ns). The only structural parameter that differed between groups was Time 1 pubertal timing to Time 2 older male friends (Δχ 2 = 10.24 (1), p < .01). For the comparison group the parameter was positive and significant (B = .24, SE = .07, p < .01), whereas for the maltreated group it was not significant (B = .02, SE = .08, ns). For the comparison group, early pubertal timing was associated with having more older male friends, whereas this relationship was not significant for maltreated adolescents.

Discussion

Studies have rarely examined the temporal relationship between sexual activity and delinquency. Much of the literature assumes that both delinquency and sexual activity are symptoms of a syndrome of problem behavior with delinquency being exhibited earlier than sexual activity (Armour and Haynie 2007; Siebenbruner et al. 2007). Importantly these pathways have not been examined in relationship to pubertal timing, a known risk factor for both outcomes (Flannery et al. 1993). The purpose of this longitudinal study was to examine characteristics of adolescents’ friendship networks as mediators between pubertal timing and sexual activity or delinquency. In addition, the analyses aimed to unravel the temporal pathway between puberty, sexual activity, and delinquency.

In order to examine the medational and temporal relationships, two competing hypotheses were tested. First, it was hypothesized that early pubertal timing would predict risky friendship networks (i.e. male friends, older friends, older male friends), which would increase subsequent sexual activity and delinquency. Second, it was hypothesized that early pubertal timing would predict increased sexual activity and subsequently more risky friends and delinquency. Our analyses provide support for the second hypothesis; we found that early pubertal timing predicted more advanced sexual activity, which subsequently predicted higher delinquency. This mechanism was similar for males and females as well as for maltreated and comparison adolescents. However, the models also showed that early pubertal timing predicted having more older friends at Time 2, which counter to expectations, predicted less sexual activity at Time 3. This was not a significant mediation effect, whereas the path from puberty to sexual activity to delinquency was significant, indicating that having older friends is not the mechanism by which early maturers become delinquent or sexually active. However, having older male friends at Time 1 independently contributed to higher sexual activity Time 2, so there may be an additive effect of early puberty and older male friends on sexual activity. In addition, the parameter from Time 1 pubertal timing to Time 2 older friends/older male friends was moderated by maltreatment status; early pubertal timing was related to having more older friends/older male friends for the comparison group but not for the maltreatment group. This finding may be due in part to the interpersonal problems evidence by maltreated children. Overall, maltreated children show elevated aggression toward or withdrawal from peers and they are more likely than nonmaltreated children to bully others (Cicchetti and Toth 2005). They are also more likely to be rejected by peers repeatedly across childhood to adolescence (Bolger and Patterson 2001). Thus, early maturing maltreated children may repel the older peers that early maturing comparison children attract.

These results contrast much of the established literature in a number of ways. First, there are several studies reporting that early pubertal timing is related to more interactions with older friends or males (Caspi et al. 1993; Stattin and Magnusson 1990), and that having older friends or male friends is associated with increased delinquency (Agnew and Brezina 1997; Kirby 2002). However, these studies were conducted primarily with females whereas our sample consisted of both genders. In addition, deviant friends have been found to mediate the association between early pubertal timing and delinquency or substance use (Costello et al. 2007; Lynne et al. 2007; Negriff et al., in press). Perhaps it is not simply older friends or male friends who influence the delinquency and sexual activity of early maturing adolescents. Conceivably, what matters is the actual delinquency or sexual activity of those friends (Caspi et al. 1993). A number of studies have found that adolescents are more likely to have sex or to initiate sex when they think that their peers are themselves having sex (Kinsman et al. 1998; O’Donnell et al. 2003). In addition, Haynie (2003) found that, for females, neither older friends nor male friends accounted for the association between early pubertal timing and delinquency, rather it was mediated by involvement in romantic relationship and friends’ delinquency. It would be particularly useful to have information about the friendship network as well as the perceived delinquency and sexual activity of those friends in order to more comprehensively examine the influence of friends.

The findings regarding the associations between pubertal timing, sexual activity, and delinquency were particularly interesting. Contrary to other studies, we found that sexual activity preceded delinquency (although the two were highly correlated cross-sectionally). Specifically, early pubertal timing was related to higher sexual activity at Time 2 which was related to higher delinquency at Time 3. This result supports the view that the hormonal processes associated with puberty pique the adolescent’s interest in sexual activity, and this sexual arousal may put them in contact with individuals who may be both sexually active and delinquent, thus increasing their subsequent delinquency. Because sexual activity and delinquency are highly correlated (Devine et al. 1993), it is likely that an individual with whom the early maturing adolescent is sexually active, is also delinquent.

Based on our findings, we propose that perhaps the early maturing adolescent is an active participant in the initiation of sexual activity. This interpretation is consistent with the models proposed by Brooks-Gunn et al. (1994) suggesting that hormone changes can have both a direct and indirect effect on negative affect with internal states of reactivity (arousal) or secondary sexual characteristics as mediators. However, in this study we cannot determine whether hormones are responsible for the increase in sexual activity or if the emergence of secondary sexual characteristics (physical manifestations of hormonal processes) are spurring the adolescents to seek out sexual partners. Our interpretation of the results differs from theories proposing that early maturers are seen as more physically mature by older adolescents and are drawn into mature activities (e.g. drinking, sex, delinquency) by older peers. However, we are not negating the influence of peers. Perhaps once the early maturing adolescent is part of these peer groups, exposure to other behaviors such as delinquency perpetuates both sexual activity and delinquent behaviors. Our results also indicate that different mechanisms may link puberty with sexual activity versus delinquency. In a previous analyses, we found that exposure to peer delinquency mediated the relationship between early pubertal timing and later delinquency (Negriff et al., in press). Other studies also have found that delinquent peers mediate the association between early pubertal timing and delinquency (Caspi et al. 1993; Lynne et al. 2007). Based on our previous work and the present findings, we posit that most early maturers may not become delinquent if they are not exposed to deviant peers. On the other hand, it seems that early maturers will become sexually active regardless of whether they associate with older versus same-age peers.

The characteristics of friends seem to have more influence on delinquency than sexual activity. Interestingly, the association between Time 2 older friends and Time 3 delinquency was positive for males but negative for females, indicating that for males having more older friends at Time 2 increased Time 3 delinquency, whereas for females having more older friends at Time 2 decreased Time 3 delinquency. There was a similar moderation effect for older male friends and delinquency; for males the coefficient was positive and significant, but for females it was not significant. There is some evidence that males are more susceptible to peer influence than females, in part explaining this effect (Sumter et al. 2008). Regarding sexual activity, surprisingly sexual activity at Time 3 was lower for those adolescents with older friends at Time 2; this finding was not moderated by gender or maltreatment status. The evidence to date shows that older friends are a risk for sexual activity (Kirby 2002), not protective as we found. Perhaps in some contexts, older friends function more as protective older siblings than provocateurs of sexual activity (Widmer 1997). Another explanation is that adolescents who have older friends may be cognitively more mature than their same-age peers and thus seek out individuals (e.g. older friends) with similar functioning. Their cognitive maturity may also allow them to withstand pressures to engage in sexual activity. Clearly, there needs to be further investigation of these mechanisms in order to understand the risks of older friends for early maturing adolescents.

Limitations of this study should be noted as well. First, both sexual activity and delinquency are behaviors that increase in mid- to late adolescence. Thus, at the first timepoint of this study there may be a restriction in the variance of sexual activity or delinquency, reducing the ability to detect significant effects later on. Although the analyses controlled for age, there are still advantages in more developmentally sensitive designs analyzed by age cohort rather than study visit. However, we feel that because our age range was not very wide we are still capturing relevant developmental differences. The choice to keep the data by timepoint was determined particularly for examining pubertal timing as we are interested primarily in the longitudinal effects of pubertal timing at Time 1 on later delinquency and sexual activity. We controlled for race in our analyses but did not investigate differences between races, per se. Therefore, although we can say these effects were found in a racially diverse sample, we cannot specifically say these associations hold for Whites versus Black versus Latinos unless we conduct a multiple group analyses. Lastly, all measures were self-report and may produce biased reporting of pubertal stage, number of friends, delinquency, and sexual activity. Other studies have found males to be more sexually active (De Gaston et al. 1996; Singh et al. 2000) as did we, but there may also be more social pressure for males to be sexually mature. There is also social stigma that goes along with females being sexually active. Males are congratulated for sexual exploits whereas females are degraded (Crawford and Popp 2003). For adolescents with interpersonal problems there may be social desirability pressures to report more friends that they actually have, or they may see having older friends as a mark of being “cool”. Lastly, the rates of both sexual activity and delinquency in this sample were relatively low, indicating that these behaviors are not particularly problematic but perhaps reflect a normative developmental trend. However, it is still worrisome that early maturers, who are possibly cognitively unprepared, are engaging in behaviors that are normative for older adolescents, but not necessarily for them. This may result in greater long-tem problems as these early maturers attempt to cope with the pressures and responsibilities associated with early sexual activity, delinquency, and criminal behavior.

This study makes substantial contributions to the pubertal timing literature. Foremost, we find that sexual activity mediates the association between pubertal timing and delinquency. Second, sexual activity precedes delinquency, providing support for a temporal pathway between the two. Our finding that, for males, having older friends and older male friends increases subsequent delinquency is an important key for pinpointing interventions. Additionally, recognizing that early timing puts an adolescent at risk for sexual activity may be integral for developing sexual education programs for school regarding the pubertal transition and related growth. As adolescents are entering puberty at an earlier age than in the past (Sun et al. 2002), there is a need to implement programs at an earlier age, perhaps before they have even begun pubertal development. Adolescents may not be deterred from sexual activity, but early education could circumvent many issues that are associated with early sexual activity such as sexually transmitted infections, risky sexual behavior, unprotected sex, and teenage pregnancy (O’Donnell et al. 2001). The longitudinal findings are important as they reveal associations that have not to date been reported, principally the temporal sequence between pubertal timing, sexual activity and delinquency.

References

Agnew, R., & Brezina, T. (1997). Relational problems with peers, gender and delinquency. Youth and Society, 29, 84–112.

Anthonysamy, A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). Peer status and behaviors of maltreated children and their classmates in the early years of school. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 971–991.

Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling (pp. 243–277). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2007). Amos 18.0. Crawfordville, FL: Amos Development Corporation.

Armour, S., & Haynie, D. L. (2007). Adolescent sexual debut and later delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 141–152.

Bogat, G. A., Chin, R., Sabbath, W., & Schwartz, C. (1985). The children’s social support questionnaire. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Bolger, K. E., & Patterson, C. J. (2001). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development, 72(2), 549–568.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Graber, J. A., & Paikoff, R. L. (1994). Studying links between hormones and negative affect: Models and measures. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 4(4), 469–486.

Brown, J. D., Halpern, C. T., & Ladin L’Engle, K. (2005). Mass media as a sexual super peer for early maturing girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36, 420–427.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Best methods for the analysis of change (pp. 136–162). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Caminis, A., Henrich, C., Ruchkin, V., Schwab-Stone, M., & Martin, A. (2007). Psychosocial predictors of sexual initiation and high-risk sexual behaviors in early adolescence. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 1, 1–14.

Caspi, A., Lynam, D., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1993). Unraveling girls’ delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 19–30. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.1029.1031.1019.

Cavanagh, S. E. (2004). The sexual debut of girls in early adolescence: The intersection of race, pubertal timing, and friendship group characteristics. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14(3), 285–312.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2005). Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 409–438.

Costello, E. J., Sung, M., Worthman, C., & Angold, A. (2007). Pubertal maturation and the development of alcohol use and abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88S, S50–S59.

Cota-Robles, S., Neiss, M., & Rowe, D. C. (2002). The role of puberty in violent and nonviolent delinquency among Anglo American, Mexican-American, and African American boys. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17(4), 364–376. doi:310.1177/07458402017004003.

Crawford, M., & Popp, D. (2003). Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. The Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 13–26.

Crockett, L. J., Bingham, R., Chopak, J. S., & Vicary, J. R. (1996). Timing of first sexual intercourse: The role of social control, social learning, and problem behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(1), 89–111.

De Gaston, J. F., Weed, S., & Jensen, L. (1996). Understanding gender differences in adolescent sexuality. Adolescence, 31(121), 217–231.

Devine, D., Long, P., & Forehand, R. (1993). A prospective study of adolescent sexual activity: Description, correlates, and predictors. Advances in Behavior Research and Therapy, 15, 185–209.

Dorn, L. D., Susman, E. J., Nottelmann, E. D., Inoff-Germain, G., & Chrousos, G. P. (1990). Perceptions of puberty: Adolescent, parent, and health care personnel. Developmental Psychology, 26, 322–329.

Elliott, D. S., & Morse, B. J. (1989). Delinquency and drug use as risk factors in teenage sexual activity. Youth and Society, 21, 32–60.

Finkelstein, J. W., Susman, E. J., Chinchilli, V. M., D’Arcangelo, M. R., Kunselman, S. J., Schwab, J., et al. (1998). Effects of estrogen or testosterone on self-reported sexual responses and behaviors in hypogonadal adolescents. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 83(7), 2281–2285.

Flannery, D. J., Rowe, D. C., & Gulley, B. L. (1993). Impact of pubertal status, timing, and age on adolescent sexual experience and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8(1), 21–40. doi:10.1177/074355489381003.

Ge, X., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H. (2001). Pubertal transition, stressful life events and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology, 37(3), 404–417. doi:410.1037/0012-1649.1037.1033.1404.

Graber, J. A., Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997). Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(12), 1768–1776. doi:1710.1097/00004583-199712000-199700026.

Halpern, C. T., Udry, R., Campbell, B., & Suchindran, C. (1993). Testosterone and pubertal development as predictors of sexual activity. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 436–447.

Halpern, C. T., Udry, R., & Suchindran, C. (1997). Testosterone predicts initiation of coiutus in adolescent females. Psychosomatic Medicine, 59, 161–171.

Haynie, D. L. (2003). Contexts of risk? Explaining the link between girls’ pubertal development and their delinquent involvement. Social Forces, 82(1), 355–397. doi:310.1353/sof.2003.0093.

Huizinga, D., & Elliott, D. S. (1986). Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 2(4), 293–327.

Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12(8), 597–605.

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Marttunen, M., Rantanen, P., & Rimpela, M. (2003). Early puberty is associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence. Social Science and Medicine, 57(6), 1055–1064. doi:1010.1016/S0277-9536(1002)00480-X.

Kinsman, S., Romer, D., Furstenberg, F., & Schwarz, D. (1998). Early sexual initiation: The role of peer norms. Pediatrics, 102, 1185–1192.

Kirby, D. (2002). Antecedents of adolescent initiation of sex, contraceptive use, and pregnancy. American Journal of Health Behavior, 26(6), 473–485.

Lynne, S. D., Graber, J. A., Nichols, T. R., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Botvin, G. J. (2007). Links between pubertal timing, peer influences, and externalizing behaviors among urban students followed through middle school. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(2), 181.e187–181.e113. doi:110.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.1009.1008.

Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. M. (1969). Variations in patterns of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 44, 291–303.

Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. M. (1970). Variations in patterns of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 45, 13–23.

Mennen, F. E., Kim, K., Sang, J., & Trickett, P. K. (2010). Child neglect: Definition and identification of adolescents’ experiences. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34, 647–658. doi:610.1016/j.chiabu.2010.1002.1007.

Miller, B. C., Norton, M. C., Fan, X., & Christopherson, C. R. (1998). Pubertal development, parental communication, and sexual values in relation to adolescent sexual behaviors. Journal of Early Adolescence, 18(1), 27–52.

Morris, N. M., & Udry, R. J. (1980). Validation of a self-administered instrument to assess stage of adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 9(3), 271–280.

Muthén, B., Kaplan, D., & Hollis, M. (1987). On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika, 52, 431–462.

Negriff, S., Fung, M. T., & Trickett, P. K. (2008). Self-rated pubertal development, depressive symptoms and delinquency: Measurement issues and moderation by gender and maltreatment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(6), 736–746. doi:710.1007/s10964-10008-19274-y.

Negriff, S., Ji, J., & Trickett, P. K. (in press). Exposure to peer delinquency as a mediator between self-report pubertal timing and delinquency: A longitudinal study of mediation. Development and Psychopathology.

Noll, J. G., Trickett, P. K., & Putnam, F. W. (2003). A prospective investigation of the impact of childhood sexual abuse on the development of sexuality. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 575–586.

O’Donnell, L., Myint-U, A., O’Donnell, C., & Stueve, A. (2003). Long-term influence of sexual norms and attitudes on timing of sexual initiation among urban minority youth. Journal of School Health, 73(2), 68–75.

O’Donnell, L., O’Donnell, C. R., & Stueve, A. (2001). Early sexual initiation and subsequent sex-related risks among urban minority youth: The reach for health study. Family Planning Perspectives, 33(6), 268–275.

Obeidallah, D., Brennan, R. T., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Earls, F. (2004). Links between pubertal timing and neighborhood contexts: Implications for girls’ violent behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(12), 1460–1468. doi:1410.1097/1401.chi.0000142667.0000152062.0000142661e.

Persky, H., Dreisbach, L., Miller, W. R., O’Brien, C. P., Khan, M. A., Lief, H. I., et al. (1982). The relations of plasma androgen levels to sexual behaviors and attitudes of women. Psychosomatic Medicine, 44(4), 305–319.

Petersen, A. C., Crockett, L. J., Richards, M., & Boxer, A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17, 117–133.

Rosenthal, D. A., Smith, A. M. A., & de Visser, R. (1999). Personal and social factors influencing age at first sexual intercourse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28(4), 319–333.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: Wiley.

Schafer, J. L. (1999). NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model (version 2.0). http://www.stat.psu.edu/~jls/misoftwa.html.

Schofield, H. T., Bierman, K. L., Heinrichs, B., & Nix, R. L. (2008). Predicting early sexual activity with behavior problems exhibited at school entry and in early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 1175–1188.

Shapiro, D. L., & Levendosky, A. A. (1999). Adolescent survivors of childhood sexual abuse: The mediating role of attachment style and doping in psychological and interpersonal functioning. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23(11), 1175–1191.

Shirtcliff, E. A., Dahl, R. E., & Pollak, S. D. (2009). Pubertal development: Correspondence between hormonal and physical development. Child Development, 80(2), 327–337.

Siebenbruner, J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Egeland, B. (2007). Sexual partners and contraceptive use: A 16-year prospective study predicting abstinence and risk behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(1), 179–206.

Simmons, R. G., & Blyth, D. A. (1987). Moving into adolescence: The impact of pubertal change and school context. New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Singh, S., Wulf, D., Samara, R., & Cuca, Y. P. (2000). Gender differences in the timing of first intercourse: Data from 14 countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 26(1), 21–28.

Stattin, H., & Magnusson, D. (1990). Paths through life: Vol. 2. Pubertal maturation in female development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sumter, S. R., Bokhorst, C. L., Steinberg, L., & Westenberg, P. M. (2008). The developmental pattern of resistance to peer influence in adolescence: Will the teenager ever be able to resist? Journal of Adolescence, 32(4), 1009–1021. doi:1010.1016/j.adolescence.2008.1008.1010.

Sun, S. S., Schubert, C. M., Chumlea, W. C., Roche, A. F., Kulin, H. E., Lee, P. A., et al. (2002). National estimates of the timing of sexual maturation and racial differences among US children. Pediatrics, 110(5), 911–919. doi:910.1542/peds.1110.1545.1911.

Tubman, J. G., Windle, M., & Windle, R. C. (1996). The onset and cross-temporal patterning of sexual intercourse in middle adolescence: Prospective relations with behavioral and emotional problems. Child Development, 67(2), 327–343.

Udry, R. (1988a). Biological predispositions and social control in adolescent sexual behavior. American Sociological Review, 53(5), 709–722.

Udry, R. (1988b). The sexual activity questionnaire for girls and boys. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina.

Widmer, E. D. (1997). Influence of older siblings on initiation of sexual intercourse. Journal of Marriage and Family, 59(4), 928–938.

Williams, J. M., & Dunlop, L. C. (1999). Pubertal timing and self-reported delinquency among male adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 157–171. doi:110.1006/jado.1998.0208.

Zingraff, M. T., Leiter, J., Myers, K. A., & Johnson, M. C. (1993). Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology, 31, 173–202.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from a National Institutes of Health R01 grant HD39129, Penelope K. Trickett P.I.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Negriff, S., Susman, E.J. & Trickett, P.K. The Developmental Pathway from Pubertal Timing to Delinquency and Sexual Activity from Early to Late Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 40, 1343–1356 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9621-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9621-7