Abstract

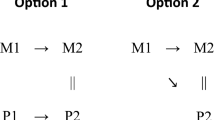

The paper argues that mental causation can be explained from the sufficiency of counterfactual dependence for causation together with relatively weak assumptions about the metaphysics of mind. If a physical event counterfactually depends on an earlier physical event, it also counterfactually depends on, and hence is caused by, a mental event that correlates with (or supervenes on) this earlier physical event, provided that this correlation (or supervenience) is sufficiently modally robust. This account of mental causation is consistent with the overdetermination of physical events by mental events and other physical events, but does not entail it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The classical statement of this problem is Malcolm 1968.

The example is from Lewis 1986a, 214.

For a recent discussion of pre-emption cases, see Collins et al. 2004.

See Lewis 2004a, 78. Hall (2004, 226) claims that “it is probably safe to say that [the sufficiency of counterfactual dependence between wholly distinct events for causation] is the cornerstone of every counterfactual analysis” (though he later argues that this sufficiency conflicts with other plausible constraints on causation, entailing the existence of two different concepts of causation).

See Lewis 1986b, 262–266.

Moreover, it is plausible that the non-backtracking reading of counterfactuals is the standard reading of counterfactuals and that a backtracking reading is an option only in special circumstances, such as those where peculiar constructions like ‘this would have to have been a case where’ are used in the formulation of the counterfactual under consideration; see Lewis 1979, 33–35.

See Garrett 1998 and Sider 2003. Some authors endorse slight variants of this definition of overdetermination. For instance, Kim (1998, 64) requires that the overdetermining events be “sufficient” causes of the overdetermined event; Funkhouser (2002, 335) holds that “overdetermination occurs when there are two or more (minimally) sufficient and distinct causes for the same effect”; and Marcus (2005, 31) requires that an overdetermined event have a “complete physical causal history”. By contrast, Mellor (1995), Mills (1996), Bennett (2003), Schaffer (2003), and Yablo (2004) characterise overdetermination in a way that comes closer to the Lewisian definition suggested below.

See Schaffer 2003 for a recent defence of the view that overdetermining events are individual causes of the overdetermined event.

The situation might be different for natural kinds. Perhaps ‘water’ is defined to be H2O (in some sense of ‘defined’), even though it is not prima facie clear that paradigm samples of water are samples of H2O (in some sense of ‘prima facie clear’). At any rate, overdetermination does not seem to be relevantly similar to natural kinds in this respect.

This definition is a generalisation of one endorsed by Lewis (1986c, 193–200) for the case of two overdetermining events. Our definition has the welcome corollary that no single-membered set of events can overdetermine another event, at least if the occurrence of this single member is contingent. (It may be doubted that there are any events that occur necessarily; if there are indeed no such events, the qualification can be dropped.) For suppose that A has just one member a. Then the definition implies that A overdetermines b if and only if (1) b would still have occurred if a had not occurred while all the other members of A had, (2) b would not have occurred if a had not occurred, and (3) a has an equally good (or bad) claim as a to cause b. Since there are no members in A except a, it is vacuously true that all members of A other than a occur if a occurs. Thus, (1) reduces to the claim that b would still have occurred if a had not occurred, while (2) says that b would not have occurred if a had not occurred. Given that a could have failed to occur, these conditions are inconsistent, so b is not overdetermined by A. (In order to derive this result formally, we can read clause (i) of the definition as ∀x(x ∈ A ⊃ (∀y(y ∈ A–{x} ⊃ Oy) & ¬Ox))

Ob)) and clause (ii) as ∀x(x ∈ A ⊃ ¬Ox)

Ob)) and clause (ii) as ∀x(x ∈ A ⊃ ¬Ox)  ¬Ob, where ‘Ox’ means that x occurs and ‘

¬Ob, where ‘Ox’ means that x occurs and ‘ ’ is the counterfactual conditional.). It follows immediately from this corollary that not all subsets of a set that overdetermines some event b overdetermine b themselves, since no single-membered subsets with contingently occurring members will overdetermine b. Larger subsets of overdetermining sets do not automatically overdetermine b either. For instance, assume that Smith is shot by a firing squad of three such that his death is overdetermined by the set of the three firings f

1, f

2, and f

3. Given that a single shot would have sufficed to kill Smith, none of the sets {f

1, f

2}, {f

1, f

3} and {f

2, f

3} in itself overdetermines the death, since in this case the latter would still have occurred because of the third firing even if all the respective members of one of these sets had not occurred. Thus, these two-membered subsets violate clause (ii) of the definition. I do not find this result problematic, but if one wishes to ensure that subsets of overdetermining sets like these also count as overdetermining, one could modify the definition as follows: A overdetermines b if and only if either clauses (i)–(iii) of the above definition are satisfied, or A is a subset with at least two members of some set A′ that satisfies (i)–(iii) together with b.

’ is the counterfactual conditional.). It follows immediately from this corollary that not all subsets of a set that overdetermines some event b overdetermine b themselves, since no single-membered subsets with contingently occurring members will overdetermine b. Larger subsets of overdetermining sets do not automatically overdetermine b either. For instance, assume that Smith is shot by a firing squad of three such that his death is overdetermined by the set of the three firings f

1, f

2, and f

3. Given that a single shot would have sufficed to kill Smith, none of the sets {f

1, f

2}, {f

1, f

3} and {f

2, f

3} in itself overdetermines the death, since in this case the latter would still have occurred because of the third firing even if all the respective members of one of these sets had not occurred. Thus, these two-membered subsets violate clause (ii) of the definition. I do not find this result problematic, but if one wishes to ensure that subsets of overdetermining sets like these also count as overdetermining, one could modify the definition as follows: A overdetermines b if and only if either clauses (i)–(iii) of the above definition are satisfied, or A is a subset with at least two members of some set A′ that satisfies (i)–(iii) together with b.Bennett (2003, 479) makes a similar point by arguing that one of two overdetermining events may counterfactually depend on the other without threatening the claim that the overdetermined event would still have occurred if only one of the overdetermining events had occurred. She conjectures that it might be the norm in firing squad cases that “if either gunman were to shoot, the other would as well, and if one did not, the other would not either”. Together with the assumption that Smith’s death would not have occurred if neither gunman had shot, this yields that Smith’s death counterfactually depends on each shooting. I suspect, however, that an illegitimate ‘backtracking’ reading of the counterfactual ‘If either gunman had not shot, the other would not have shot either’ is in play here: in a standard firing squad case, this counterfactual seems plausible only if read such that, if either gunman had not shot, this would have to have been a case where the squad was not ordered to shoot and hence neither gunman shot.

That Smith’s death would not have occurred if neither bandit had fired follows logically from the counterfactual dependence of the death on the individual firings plus the claim that the death would still have occurred if either bandit had fired while the other had not; see note 30 below.

The strategy of explaining mental causation via counterfactual dependence is also explored in Baker 1993, Horgan 1997 and Horgan 2001. Kim (1998, 71) criticises the (earlier) attempts for merely claiming that certain mind-body counterfactuals are true without giving an account of why they are true. The following sections try to develop such an account.

Comparatively speaking, all the worlds in a sphere are more similar to the actual world than any worlds outside the sphere. The properties of spheres are discussed in Lewis 1973b, 13–19.

See Lewis 1973b, 16.

It may seem that we can find a unique verifying sphere for each non-vacuously true counterfactual if we take its smallest verifying sphere. However, it is not generally the case that there is such a smallest sphere: see Lewis 1973b, 19–21.

I am speaking of mental events occurring ‘in the mind’ and physical events occurring ‘in the brain’ of a person merely in order to be able to assign physical and mental events to particular persons. This terminology is not supposed to rule out that mental events or their physical correlates may extend into the person’s environment by virtue of content externalism.

Of course every token event belongs to a plethora of types, some of them utterly trivial, such as the type toothache-or-something-else. While arguably this gives rise to the so-called generality problem in epistemology (see Feldman 1985), in our context of mental and physical token events the relevant mental and physical types will be easily identifiable.

Consider the principle that an event that has a physical cause (or perhaps a complete physical cause, in some intuitive sense of ‘complete’) cannot also have a distinct mental cause. To the extent that someone finds this principle plausible, she is likely to be suspicious about the soundness of the argument presented in this section. In particular, she is likely to doubt sufficiency if she holds that mental and physical events are distinct. I concede that the principle has some initial appeal; however, I take this to be outweighed by the independent plausibility of sufficiency.

The assumption that t does not occur in some world in this verifying sphere is not a gratuitous one. If we conceive of p 1, p 2, ... p k as sufficiently dissimilar events, and assume that the closest world v where p 1 fails to occur is sufficiently similar to the actual world, it seems plausible that it could more easily have happened that none of p 1, p 2, ... p k should have occurred than that one of p 2, ... p k should have occurred instead of p 1. Thus, if p 1 had not occurred, neither would any of p 2, ... p k have occurred. Given that v is in the sphere of supervenience, it follows that t does not occur in v either. (The assumption that there is a unique closest world v where p 1 fails to occur was made merely for simplicity.)

Alternatively, one could focus not on the single physical event that accompanies a given mental event but rather on the whole range of physical events it supervenes on: instead of demanding that w would not have occurred if p 1 had not occurred, we could demand that w would not have occurred if none of p 1, p 2, ... p k had occurred. If t supervenes on p 1, p 2, ... p k in a sphere that is large enough to contain a sphere that verifies the counterfactual ‘If none of p 1, p 2, ... p k had occurred, w would not have occurred’, it follows that w would not have occurred if t would not have occurred. The logic behind this argument parallels that of the previous section; we merely need to replace the occurrence of the c-fibre firing c that was assumed to correlate with t with the occurrence of either p 1 or p 2 or ... p k . Note that this strategy, while yielding the causation of w by t, may not yield multiple causation of w since it leaves it open that w does not counterfactually depend on (and thus perhaps is not caused by) any single physical event.

Strictly speaking, establishing that the toothache is t does not require mental and physical token events to have the same degree of fragility in S. It would suffice if it were merely the case that mental events did not have a higher degree of fragility than physical events in S. That is, it would suffice if the following were true: for all worlds v and u in S, if some token mental event accompanies some token physical event in v, then if the physical event is accompanied by some event of the mental event’s type in u, the latter event is identical with the other original token mental event occurring in v.

Since ‘P & Q

R’ is a logical consequence of ‘P

R’ is a logical consequence of ‘P  R’ and ‘P & ¬Q

R’ and ‘P & ¬Q  ¬R’ on Lewis’s semantics (see below), it follows from w’s counterfactual dependence on c plus the assumption that w would still have occurred if c had not occurred while t had that w would not have occurred if neither c nor t had occurred (we merely need to replace ‘P’ with ‘c does not occur’, ‘Q’ with ‘t does not occur’, and ‘R’ with ‘w does not occur’). Similarly, that w would not have occurred if neither c nor t had occurred follows from w’s counterfactual dependence on t plus the assumption that w would still have occurred if t had not occurred while c had. Thus, if w counterfactually depends both on c and on t, and w would not have occurred if either of c and t had not occurred while the other had, condition (c) (viz. the condition that w would not have occurred if neither c nor t had occurred) will automatically be satisfied, independently of the correlation between c and t.

¬R’ on Lewis’s semantics (see below), it follows from w’s counterfactual dependence on c plus the assumption that w would still have occurred if c had not occurred while t had that w would not have occurred if neither c nor t had occurred (we merely need to replace ‘P’ with ‘c does not occur’, ‘Q’ with ‘t does not occur’, and ‘R’ with ‘w does not occur’). Similarly, that w would not have occurred if neither c nor t had occurred follows from w’s counterfactual dependence on t plus the assumption that w would still have occurred if t had not occurred while c had. Thus, if w counterfactually depends both on c and on t, and w would not have occurred if either of c and t had not occurred while the other had, condition (c) (viz. the condition that w would not have occurred if neither c nor t had occurred) will automatically be satisfied, independently of the correlation between c and t. Here is an informal proof of the logical principle used above. Assume (1) P

R, and (2) P & ¬Q

R, and (2) P & ¬Q  ¬R. We have to show that this yields (3) P & Q

¬R. We have to show that this yields (3) P & Q  R. Assume that P is true in some world. (If P is false in all worlds, (1)–(3) are vacuously true.) If P is true in some world, (1) is non-vacuously true if true, so from the assumption of its truth, we get that there is a non-empty set W of worlds where P and R are true that are closer to the actual world than all worlds where P is true while R is false. Now suppose that W contains a world v where Q is false. Then, in v, P is true while Q is false and R is true. Further, v is closer to the actual world than all worlds where P is true while both Q and R are false (since, like all worlds in W, v is closer to the actual world than any worlds where P is true and R is false). Thus, ‘P & ¬Q

R. Assume that P is true in some world. (If P is false in all worlds, (1)–(3) are vacuously true.) If P is true in some world, (1) is non-vacuously true if true, so from the assumption of its truth, we get that there is a non-empty set W of worlds where P and R are true that are closer to the actual world than all worlds where P is true while R is false. Now suppose that W contains a world v where Q is false. Then, in v, P is true while Q is false and R is true. Further, v is closer to the actual world than all worlds where P is true while both Q and R are false (since, like all worlds in W, v is closer to the actual world than any worlds where P is true and R is false). Thus, ‘P & ¬Q  R’ is non-vacuously true, which contradicts (2). Consequently, there is no such world as v, and Q is true in all worlds in W. So in all worlds in W, all of P, Q and R are true, and the worlds in W are closer to the actual world than all worlds where P and Q are true while R is false (since the worlds in W are closer to the actual world than any worlds where P is true and R is false). Hence, (3) is non-vacuously true.

R’ is non-vacuously true, which contradicts (2). Consequently, there is no such world as v, and Q is true in all worlds in W. So in all worlds in W, all of P, Q and R are true, and the worlds in W are closer to the actual world than all worlds where P and Q are true while R is false (since the worlds in W are closer to the actual world than any worlds where P is true and R is false). Hence, (3) is non-vacuously true.What if the correlation between c and t is necessary (that is, if the sphere throughout which c and t correlate coincides with the modal universe)? In this case, (a) and (b) would be vacuously true. Nevertheless, I would be inclined not to categorise such a case as one of overdetermination. For it is doubtful that c and t would still be distinct events. But if c is identical with t, we are dealing with a single contingently occurring event, and, as was shown in note 14 above, no single-membered set containing a contingently occurring event can overdetermine anything. On a related point, see Bennett 2003, 479–480.

Thus defined, the asymmetric overdetermination of e by the pair <a, b> may be incompatible with the overdetermination proper of e by the set {a, b} according to our definition. For the latter demands that e would still have occurred if a had occurred without b, which contradicts clause (i) of the definition of asymmetric overdetermination if it is possible for a to occur without b. It may also seem that if the pair <a, b> asymmetrically overdetermines e, b has a better claim to be a cause of e than a has, while overdetermination proper requires a and b to have an equally good (or bad) claim to be a cause of e.

By contrast, there seems to be no problem about the causal efficacy of c in such a case.

See Lewis 1986c, 193.

I would like to thank Jeremy Butterfield, Antony Eagle, Ralph Wedgwood, and Timothy Williamson for helpful comments and suggestions.

References

Baker, L. R. (1993). Metaphysics and mental causation. In J. Heil, & A. Mele (Eds.), Mental Causation Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Beebee, H. (2004) Causing and Nothingness. In Collins, Hall & Paul 2004.

Bennett, J. F. (1988). Events and their names. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Bennett, K. (2003). Why the exclusion problem seems intractable, and how, just maybe, to tract it. Noûs, 37, 471–497.

Collins, J., Hall, N., & Paul, L. A. (Eds.) (2004). Causation and counterfactuals. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Crane, T. (1995). The mental causation debate. Supplement to the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 69, 211–236.

Feldman, R. (1985). Reliability and justification. Monist, 68, 159–174.

Funkhouser, E. M. (2002). Three varieties of causal overdetermination. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 83, 335–351.

Garrett, B. J. (1998). Pluralism, causation and overdetermination. Synthese, 116, 355–378.

Goldman, A. I. (1969). The compatibility of mechanism and purpose. Philosophical Review, 78, 468–482.

Hall, N. (2004). Two concepts of causation. In Collins, Hall & Paul 2004.

Horgan, T. (1997). Kim on mental causation and causal exclusion. Philosophical Perspectives, 11, 165–184.

Horgan, T. (2001). Causal compatibilism and the exclusion problem. Theoria, 16, 95–116.

Kim, J. (1973). Causes and counterfactuals. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 570–572.

Kim, J. (1976). Events as property exemplifications. In M. Brand & D. Walton (Eds.), Action Theory Dordrecht: Reidel.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Lewis, D. (1973a). Causation. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 556–567.

Lewis, D. (1973b). Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (1979). Counterfactual dependence and time’s arrow. Noûs, 13, 455–476.

Lewis, D. (1986a). Causal explanation. In Philosophical papers, (Vol. II). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1986b). Events. In Philosophical papers, (Vol. II). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1986c). Postscripts to ‘Causation’. In Philosophical papers, (Vol. II). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (2004a). Causation as influence. In Collins, Hall and Paul 2004.

Lewis, D. (2004b). Void and object. In Collins, Hall and Paul 2004.

Lombard, L. B. (1986). Events: A metaphysical study. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Malcolm, N. (1968). The conceivability of mechanism. Philosophical Review, 77, 45–72.

Marcus, E. (2005). Mental causation in a physical world. Philosophical Studies, 122, 27–50.

Mellor, D. H. (1995). The facts of causation. London: Routledge.

Menzies, P. (2004). Difference-making in context. In Collins, Hall & Paul 2004.

Mills, E. (1996). Interactionism and overdetermination. American Philosophical Quarterly, 33, 105–117.

Peacocke, C. (1979). Holistic explanation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Schaffer, J. (2003). Overdetermining causes. Philosophical Studies, 114, 23–45.

Sider, T. (2003). What’s so bad about overdetermination? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 67, 719–726.

Unger, P. (1977). The uniqueness in causation. American Philosophical Quarterly, 14, 177–188.

Yablo, S. (2004). Advertisement for a sketch of an outline of a proto-theory of causation. In Collins, Hall & Paul 2004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kroedel, T. Mental causation as multiple causation. Philos Stud 139, 125–143 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-007-9106-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-007-9106-z

Ob)) and clause (ii) as ∀x(x ∈ A ⊃ ¬Ox)

Ob)) and clause (ii) as ∀x(x ∈ A ⊃ ¬Ox)