Abstract

We examine whether local inconsistencies in the counting of votes influence voting behavior. We exploit the case of the second ballot of the 2016 presidential election in Austria. The ballot needed to be repeated because postal votes were counted carelessly in individual electoral districts (“scandal districts”). We use a difference-in-differences approach comparing election outcomes from the regular and the repeated round. The results do not show that voter turnout and postal voting declined significantly in scandal districts. Quite the contrary, voter turnout and postal voting increased slightly by about 1 percentage point in scandal districts compared to non-scandal districts. Postal votes in scandal districts also were counted with some greater care in the repeated ballot. We employ micro-level survey data indicating that voters in scandal districts blamed the federal constitutional court for ordering a second election, but did not seem to blame local authorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Section 6.3 includes survey information on voters’ attitudes toward the repeated elections and the scandal.

See, e.g., the comment of Anneliese Rohrer in the newspaper Die Presse, 18 June 2016, or the interview with Chancellor Christian Kern in OE24.at, 11 June 2016, http://www.oe24.at/oesterreich/politik/Christian-Kern-Wir-haben-eine-Chance-vergeben/239273674.

Cantú (2014) elaborates on the extent rather than on the consequences of electoral manipulation in the counting of votes in Mexico.

See Puglisi and Snyder (2011) on newspaper coverage of political scandals.

See Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 7 February 2016, “Wenigstens der österreichische Wein taugt noch was”.

Inferences do not change when we exclude those districts from the control group that were subject to constitutional court summons, but electoral inconsistencies were not confirmed (n = 6).

See Der Standard, 14 July 2016, http://derstandard.at/2000041085212/Disziplinarstellen-ermitteln-gegen-Beamte.

Vienna accounts for 23 of Austria’s 117 electoral districts.

See the 1 July 2016 press release of the Austrian constitutional court: “In the districts of Innsbruck-Land, Südoststeiermark, Stadt Villach, Villach-Land, Schwaz, Wien-Umgebung, Hermagor, Wolfsberg, Freistadt, Bregenz, Kufstein, Graz-Umgebung, Leibnitz and Reutte the rules governing the implementation of the postal voting system were not complied with…. In the districts of Kitzbühel, Landeck, Hollabrunn, Liezen, Gänserndorf and Völkermarkt the system of postal voting was implemented in accordance with the rules.”

We have no information on treatment intensity (e.g., number of affected votes).

In an earlier working paper version, we use Huber-White sandwich standard errors robust to heteroscedasticity (Huber 1967; White 1980). The treatment effects do not turn out to be significant when we use robust standard errors and do not include district fixed effects. We return to this issue in Sect. 5.3.

We divide all variables by 100 making sure that the variables assume values between 0 and 1.

We used the same specification in an earlier version of this paper. See footnote 12.

It is worth noting that we cannot address a global decline in trust.

See, for example, Die Presse, „Wahlanfechtung: ‚Vorwürfe zusammengebrochen‘“, 26 June 2016, http://diepresse.com/home/politik/innenpolitik/5035340/Wahlanfechtung_Vorwuerfe-zusammengebrochen.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee who suggested this explanation.

Trust also has been shown to be correlated with, for example, income equality and education (Knack and Keefer 1997). On social trust—as measured by the degree to which people believe that strangers can be trusted—and governance, see Bjørnskov (2010): social trust was positively associated with economic-judicial governance, but has not been shown to be associated with electoral institutions.

References

Anderson, C. J., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2003). Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 47, 91–109.

Birch, S. (2010). Perceptions of electoral fairness and voter turnout. Comparative Political Studies, 43, 1601–1622.

Bjørnskov, C. (2010). How does social trust lead to better governance? An attempt to separate electoral and bureaucratic mechanisms. Public Choice, 144, 323–346.

Cantú, F. (2014). Identifying irregularities in Mexican local elections. American Journal of Political Science, 58, 936–951.

Carreras, M., & İrepoğlu, Y. (2013). Trust in elections, vote buying, and turnout in Latin America. Electoral Studies, 32, 609–619.

Chang, E. C. C., & Chu, Y. (2006). Corruption and trust: Exceptionalism in Asian democracies? Journal of Politics, 68, 259–271.

Chang, E. C. C., Golden, M. A., & Hill, S. J. (2010). Legislative malfeasance and political accountability. World Politics, 62, 177–220.

Chong, A., de la O, A., Karlan, D., & Wantchekon, L. (2015). Does corruption information inspire the fight or quash the hope? A field experiment in Mexico on voter turnout, choice and party identification. Journal of Politics, 77, 55–71.

Citrin, J. (1974). Comment: the political relevance of trust in government. American Political Science Review, 68, 973–988.

Costas-Pérez, E., Solé-Ollé, A., & Sorribas-Navarro, P. (2012). Corruption scandals, voter information, and accountability. European Journal of Political Economy, 28, 469–484.

Cox, M. (2003). Partisanship and electoral accountability: Evidence from the UK expenses scandal. Journal of Common Market Studies, 41, 757–770.

Eggers, A. (2014). Partisanship and electoral accountability: Evidence from the UK expenses scandal. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 9, 441–472.

Escaleras, M., Calcagno, P. T., & Shughart, W. F., II. (2012). Corruption and voter participation: Evidence from the US states. Public Finance Review, 40, 789–815.

Fernández-Vázquez, P., Barberá, P., & Rivero, G. (2016). Rooting out corruption or rooting for corruption? The heterogenous electoral consequences of scandals, Political Science Research and Methods, 4, 379–397.

Ferraz, C., & Finan, F. (2008). Exposing corrupt politicians: The effects of Brazil’s publicly released audits on electoral outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123, 703–745.

Fricke, K. (1999). Die DDR-Kommunalwahlen ’89 als Zäsur für das Umschlagen von Opposition in Revolution. In E. Kuhrt (Ed.), Opposition in der DDR von den 70er Jahren bis zum Zusammenbruch der SED-Herrschaft (pp. 467–505). Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Fund, J., & von Spakovsky, H. (2012). Who’s counting? How fraudsters and bureaucrats put your vote at risk. New York: Encounter books.

Gaebler, S., Potrafke, N., & Roesel, F. (2017). Compulsory voting, voter turnout and asymmetrical habit-formation. CESifo Working Paper No. 6764.

Hansen, S. W. (2013). Polity size and local political trust: A quasi-experiment using municipal mergers in Denmark. Scandinavian Political Studies, 36, 43–66.

Hetherington, M. J. (1999). The effect of political trust on the Presidential vote, 1986-96. American Political Science Review, 93, 311–326.

Hirano, S., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2012). What happens to incumbents in scandals? Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 7, 447–456.

Huber, P. J. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In: Proceedings of the fifth berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, pp. 221–233.

Karahan, G. R., Coats, R. M., & Shughart, W. F. (2006). Corrupt political jurisdictions and voter participation. Public Choice, 126, 87–106.

Kauder, B., & Potrafke, N. (2015). Just hire your spouse! Evidence from a political scandal in Bavaria. European Journal of Political Economy, 38, 42–54.

Knack, S. (1992). Civic norms, social sanctions, and voter turnout. Rationality and Society, 4, 133–156.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital has an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 52, 1251–1287.

Lacombe, D. J., Coats, R. M., Shughart, W. F., & Karahan, G. R. (2017). Corruption and voter turnout: a spatial econometric approach. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 42, 168–185.

Larcinese, V., & Sircar, I. (2017). Crime and punishment the British Way: Accountability channels following the MPs’ expenses scandal. European Journal of Political Economy, 47, 75–99.

McCubbins, M., & Schwartz, T. (1984). Congressional oversight overlooked: Police patrols versus fire alarms. American Journal of Political Science, 28, 165–179.

Morris, S. D., & Klesner, J. L. (2010). Corruption and trust: Theoretical considerations and evidence from Mexico. Comparative Political Studies, 43, 1258–1285.

Neuwirth, E., & Schachenmayer, W. (2016). Eine Mathematik-Lektion für den VfGH. Falter, 36(16), 14–15.

Pattie, C., & Johnston, R. (2012). The electoral impact of the UK 2009 MP’s expenses scandal. Political Studies, 60, 730–750.

Potrafke, N., & Roesel, F. (2018). Opening hours of polling stations and voter turnout: Evidence from a natural experiment. Review of International Organizations (forthcoming).

Puglisi, R., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2011). Newspaper coverage of political scandals. Journal of Politics, 73, 931–950.

Rudolph, L., & Däubler, T. (2016). Holding individual representative accountable: the role of electoral systems. Journal of Politics, 78, 746–762.

Seligson, M. A. (2002). The impact of corruption on regime legitimacy: A comparative study of four Latin American countries. Journal of Politics, 64, 408–432.

Solé-Ollé, A., & Sorribas-Navarro, P. (2017). Trust no more? On the lasting effects of corruption scandals, European Journal of Political Economy (forthcoming).

Spiller, P. T. (2013). Transaction cost regulation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 89, 232–242.

Sulitzeanu-Kenan, R., Dotan, Y., & Yair, O. (2016). Judicial anti-corruption enforcement can enhance electoral accountability, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Legal Research Paper No. 16-31.

Vivyan, N., Wagner, M., & Tarlov, J. (2012). Representative misconduct, voter perceptions and accountability: Evidence from the 2009 House of Commons expenses scandal. Electoral Studies, 31, 750–763.

Weschle, S. (2016). Punishing personal and electoral corruption: Experimental evidence from India. Research and Politics, 16, 1–6.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–838.

Winters, M. S., & Weitz-Shapiro, R. (2013). Corruption as a self-fulfilling prophecy: Evidence from a survey experiment in Costa Rica. Comparative Politics, 45, 418–436.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors William F. Shughart II and Keith Dougherty, as well as Clemens Fuest, Monika Koeppl-Turyna, Andreas Steinmayr, Kaspar Wüthrich, the participants of seminar at the Technische Universität Dresden and two anonymous referees for helpful comments. We also thank Christina Matzka for sharing the micro-level survey data and Lisa Giani-Contini for proof-reading. Felix Roesel gratefully acknowledges DFG funding (Grant Number 400857762). A previous version of this paper circulated as CESifo Working Paper 6254 under the title “A Banana Republic? Trust in Electoral Institutions in Western Democracies—Evidence from a Presidential Election in Austria”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 9, 10, 11 and Fig. 3.

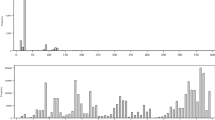

Trends of outcome variables (Vienna excluded). Notes The figure shows election outcomes of districts (Vienna excluded) which were subject to constitutional court summons (upper panel, n = 20), and districts where inconsistencies were confirmed (lower panel, n = 14). Vertical lines represent the timing of the scandal. Total number of districts: 94. 1998, 2004, 2010, 2016 (two rounds): Presidential elections. 1994, 1995, 1999, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2013: Parliamentary elections

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Potrafke, N., Roesel, F. A banana republic? The effects of inconsistencies in the counting of votes on voting behavior. Public Choice 178, 231–265 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-00626-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-00626-8

Keywords

- Elections

- Trust

- Political scandals

- Administrative malpractice

- Counting of votes

- Voter turnout

- Populism

- Natural experiment