Abstract

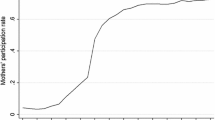

The family policy reform 2009 introduced tax deductibles for children and child care expenditures in Austria. In this paper we evaluate this reform based on a structural labor supply model with unitary households which has been estimated on the European Statistics on Income and Living Conditions cross-sections 2004–2008. We find that the reform had only small employment effects, most of them being generated through the introduction of a child care deductible. However, to illustrate the employment potential of a shift from universal child transfers to tax deductibles we propose additional simulations showing that such a policy shift would yield an increase in full time equivalents of approximately .70 % of overall employment, with married females increasing their labor supply by up to 1.5 %. While the proposed policy shifts have regressive effects in terms of their distributional impact, we show that phasing-out the tax deductible at higher income allows for the compensation of lower-income households without jeopardizing positive employment effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that we do not distinguish between marriage and partnership.

In households with only one decision maker the choice problem has a reduced form depending on only two alternative-specific variables.

Specifically, it incorporates income taxation, employee’s contributions to social insurance, welfare benefits as well as family tax credits and transfers.

The discrete approach has the advantage that it combines tractability with a detailed representation of the household budget set including any non-convexities that arise due to the complexity of the Austrian tax-benefit system (Creedy and Duncan 2002).

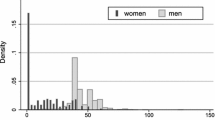

In these equations we use education, age, work experience, sector of employment, marital status and migrational background as explanantory variables. In addition to these variables, the sample correction equations include information on number of children, health status, non-labor income and previous labor market states. Estimation tables and related results are available from the authors on request.

Note that this table only serves descriptive purposes. To estimate the labor supply model presented in Sect. 4 we wage-integrate the likelihood for each non-participant using Gaussian quadrature methods.

To facilitate convergence we first estimate a model using 5 Gauss-Hermite nodes and the corresponding weights. In a second step we increase the number of nodes and weights to 10, which is the specification used to derive the presented results. To check the robustness of our estimation results we repeated this procedure with 12, 14, 16 and 20 Gauss-Hermite nodes. Additional results confirm the presented estimates and are provided as supplementary online material.

For a recent analysis of household behavior, including labor supply, household production, consumption and saving, from a life-cycle perspective see Apps and Rees (2010).

Note that for the policy simulations we exclude individuals who do not satisfy this condition.

For the estimation we take singles and individuals with inflexible partners together in one group per gender. However, for the presentation of the results we differentiate by marital status and gender to facilitate interpretation.

Additional tables presented in Hanappi and Müllbacher (2012) show that single males and females tend to be younger on average than individuals in a partnership.

Wernhart and Winter-Ebmer (2012) recently used a three-stage procedure to estimate labor supply elasticites in Austria based on repeated cross-sections from 1981 to 1999. Although their preferred estimates are lower than ours (possibly due to different empirical strategies), they confirm our results with regard to the similarity of male and female labor supply patterns.

We account for regional differences in publicly subsidized child care places.

Note that we take into account that some housholds have inactive members who can also take over child care duties.

Results from the first six reform scenarios are not reported here since they are only used to ensure revenue neutrality.

Transfers can only be received until age 24 if the child is still in education.

First round distributional effects are not reported here.

Remember that single earners are able to claim the same amount of deduction as a couple, see Table 11.

Of course, the regressive character of a tax deductible is at odds with the idea of a phase-out, however, the purpose of these simulations is to establish the feasibility of a compensating policy. If phase-outs really are to be implemented in this context, it would probably make sense to adopt tax credits instead of deductibles.

Note that other combinations of thresholds and rates will also fulfill this criterion, however, the excercise only serves the purpose to show that compensation is feasible at relatively low cost.

References

Apps, P., & Rees, R. (2010). Family labor supply, taxation and saving in an imperfect capital market. Review of Economics of the Household, 8(3), 297–323.

Apps, P., Kabatek, J., Rees, R., & van Soest, A. (2012). Labor supply heterogeneity and demand for child care of mothers with young children. IZA Discussion Papers 7007, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Bargain, O., & Orsini, K. (2006). In-work policies in Europe: Killing two birds with one stone? Labour Economics, 13, 667–697.

Bargain, O., Orsini, K., & Peichl, A. (2011). Labor supply elasticities in Europe and the US. IZA Discussion Papers 5820, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Blundell, R., Duncan, A., & Meghir, C. (1998). Estimating labor supply responses using tax reforms. Econometrica, 66(4), 827–862.

Blundell, R., Duncan, A., McCrae, J., & Meghir, C. (2000). The labour market impact of the working families’ tax credit. Fiscal Studies, 21(1), 75–103.

Brewer, M., Duncan, A., Shepard, A., & Suarez, M. (2006). Did working families’ tax credit work? The impact of in-work support on labour supply in Great Britain. Labour Economics, 13, 699–720.

Brewer, M., Ratcliffe, A., & Smith, S. (2008). Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK. IFS Working Papers 1, pp. 1–43.

Creedy, J., & Duncan, A. (2002). Behavioural mircosimulation with labour supply responses. Journal of Economic Surveys, 16, 1–40.

Dagsvik, J. K., & Jia Z. (2006). Labor supply as a choice among latent job opportunities. A practical empirical approach. Research Department of Statistics Norway: Discussion Papers, 2012, p. 481

Dagsvik, J. K., Jia, Z., Kornstad, T., & Thoresen, T. O. (2012). Theoretical and practical arguments for modeling labor supply as a choice among latent jobs. CESifo Working Paper Series, 2012, p. 3708.

Dearing, H., Hofer, H., Lietz, C., Winter-Ebmer, R., & Wrohlich, K. (2007). Why are mothers working longer hours in Austria than in Germany? A comparative microsimulation analysis. Fiscal Studies, 28(4), 463–495.

Del Boca, D., & Sauer, R. (2009). Life cycle employment and fertility across institutional environments. European Economic Review, 53, 274–292.

Donni, O., & Moreau, N. (2007). Collective labor supply: A single-equation model and some evidence from French data. Journal of Human Resources, 42(1), 214–246.

Eissa, N., & Hoynes, H. W. (2004). Taxes and the labor market participation of married couples: The earned income tax credit. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1931–1958.

Garcia, J., & Suarez, M. J. (2003). Female labour supply and income taxation in Spain: The importance of behavioural assumptions and unobserved heterogeneity specification. Hacienda Publica Espanola, 164(1), 9–27.

Gupta, N. D., Smith, N., & Verner, M. (2008). Perspective article: The impact of nordic countries? Family friendly policies on employment, wages, and children. Review of Economics of the Household, 6(1), 65–89.

Hanappi, T., & Müllbacher, S. (2012). Tax incentives and family labor supply in Austria. NRN working papers 2012-12, The Austrian Center for Labor Economics and the Analysis of the Welfare State, Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria.

Heim, B. T. (2009). Structural estimation of family labor supply with taxes: Estimating a continuous hours model using a direct utility specification. Journal of Human Resources, 44(2), 350–385.

Herbst, C. (2010). The labor supply effects of child care costs and wages in the presence of subsidies and the earned income tax credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 8(2), 199–230.

Herrarte, A., Moral-Carcedo, J., & Saez, F. (2012). The impact of childbirth on spanish women?s decisions to leave the labor market. Review of Economics of the Household, 10(3), 441–468.

Hofer, H., Koman, R., Schuh, A., & Felderer, B. (2003). Das Steuer-Transfer-Modell ITABENA. Technical report, Institute for Advanved Studies.

Hotchkiss, J., Pitts, M., & Walker, M. (2011). Labor force exit decisions of new mothers. Review of Economics of the Household, 9(3), 397–414.

Hotz, V. J., & Scholz, J. K. (2003). The earned income tax credit, volume means tested transfer programs in the United States, Chap. 3 (pp. 141–197). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hotz, J., Mullin, C., & Scholz, J. (2006). Examining the effect of the earned income tax credit on the labor market participation of families on welfare. NBER Working Paper Series, 11968:1–57

Hoynes, H. W. (1996). Welfare transfers in two-parent families: Labor supply and welfare participation under afdc-up. Econometrica, 64(2), 295–332.

Immervoll, H., Kleven, H. J., Kreiner, C. T., & Verdelin, N. (2009). An evaluation of the tax-transfer treatment of married couples in European countries. IZA Discussion Papers 3965, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Kalb, G., & Thoresen, T. (2010). A comparison of family policy designs of Australia and Norway using microsimulation models. Review of Economics of the Household, 8(2), 255–287.

Lucas, R. E. (1976). Econometric policy evaluation: A critique. Carnegie-Rochester Conference on Series Public Policy, 1, 19–46.

Lutz, H., & Schratzenstaller, M. (2010). Moegliche Ansaetze zur Unterstuetzung von Familien durch die oeffentlichen Haushalte. WIFO Monatsberichte, 8, 661–674.

Meghir, C., & Phillips, D. (2008). Labour supply and taxes. The Institute for Fiscal Studies, WP 08/04.

Meyer, B. D., & Rosenbaum, D. T. (2001). Welfare, the earned income tax credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. Quaterly Journal of Economics, 116(3), 1063–1114.

OECD (2011). Doing better for families. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Orsini, K. (2006). Tax-benefits reforms and the labor market: Evidence from Belgium and other EU countries. Center for Economic studies—discussion papers ces0606, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Centrum voor Economische Studien.

Peichl, A., Schneider, H., & Siegloch, S. (2010). Documentation IZAMOD: The IZA Policy Simulation Model. IZA Discussion Paper Series, pp. 1–30.

Pronzato, C. (2009). Return to work after childbirth: Does parental leave matter in Europe? Review of Economics of the Household, 7(4), 341–360.

Steiner, V., & Wrohlich, K. (2004). Household taxation, income splitting and labor supply incentives: A microsimulation study for Germany. Discussion Papers of DIW Berlin 421, DIW Berlin, German Institute for Economic Research.

Steiner, V., & Wakolbinger, F. (2009). The Austrian tax transfer model ATTM: Version 1.0. Technical report, Gesellschaft fuer Angewandte Wirtschaftsforschung mbH.

Train, K. E. (2009). Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Soest, A. (1995). Structural models of family labor supply. Journal of Human Resources, 30, 63–88.

Wernhart, G., & Winter-Ebmer, R. (2012). Do Austrian men and women become more equal? At least in terms of labour supply! Empirica, 39(1), 45–64.

Wrohlich, K. (2006). Labor supply and child care choices in a rationed child care market. IZA Discussion Paper Series, 2053, 1–31.

Acknowledgments

For helpful discussion and comments we would like to thank Rudolf Winter-Ebmer, Tamas Papp, Raphaela Hyee and Helmut Hofer as well as the Austrian Central Bank for financial support by means of the Jubiläumsfonds (project 13358)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hanappi, T.P., Müllbacher, S. Tax incentives and family labor supply in Austria. Rev Econ Household 14, 961–987 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9230-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9230-9