Abstract

This paper explores the determinants of start-up size by focusing on a cohort of 6,247 businesses that started trading in 2004, using a unique dataset on customer records at Barclays Bank. Quantile regressions show that prior business experience is significantly related with start-up size, as are a number of other variables such as age, education and bank account activity. Quantile treatment effects (QTE) estimates show similar results, with the effect of business experience on (log) start-up size being roughly constant across the quantiles. Prior personal business experience leads to an increase in expected start-up size of about 50 %. Instrumental variable QTE estimates are even higher, although there are concerns about the validity of the instrument.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the ‘Hubris theory of Entrepreneurship,’ Proposition 5 in Hayward et al. (2006, p. 167) posits that: “More overconfident founders start their ventures with smaller resource endowments and this increases the likelihood that their ventures will fail.”

Note that this is not the usual meaning of the word ‘entrepreneurial learning.’ In our model, entrepreneurs do not apply their learning to improve their post-entry performance, but instead they ‘learn’ to increase their chances of success by starting large—all the while recognizing that they are playing a random game.

Da Rin et al. (2010) measure entry size as the median total assets at the country-industry level, but do not apply quantile analysis.

For example, in the UK, the threshold for value added tax (VAT) registration was set at a turnover of GBP 73,000 for the 12 months from 1 April 2011. Firms below this threshold are not required to register.

We are grateful to a reviewer for bringing this to our attention.

Since we are analyzing a cross-section of data corresponding to the first year of a cohort of firms that start in the same quarter, there is no variation in time period, and hence there is no need to include year dummies.

We can infer the start-up size of those firms that do not survive their first year by taking the number of owners as a proxy for startup size. Following Colombo et al. (2004, p. 1192), we have information on number of owners at start-up for 1,053 businesses that do not survive their first year (76.5 % of which have just one owner) and 5,176 businesses that do survive their first year (71.5 % have just one owner). On this basis, it seems that there are no major differences in size between those businesses that exit before the end of the first year, and those that survive.

A Skewness-Kurtosis test of normality returns a p value of 5.63E−13.

The variable ‘number of owners’ has mean 1.320, standard deviation 0.573, minimum = 1 and maximum = 6, for 6,229 observations in the first year.

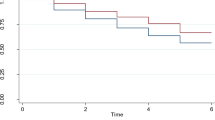

Further analysis, available from the authors upon request, shows that the effects of prior business experience (both personal and parental) show no clear trend over the quantiles (neither increasing nor decreasing).

When we repeated the estimations in Table 4 excluding these bank account variables, our results were similar to those obtained previously.

These contrasting results for availability and use of overdraft can be compared to findings in Colombo and Grilli (2005, their Table 2) that bank debt is not significantly associated with start-up size.

Previous studies that take parental characteristics as an instrument for entrepreneur’s characteristics include Dahl and Sorenson (2012).

For a similar line of reasoning, see e.g. Cassiman and Veugelers (2002, p. 1174).

References

Abadie, A., Angrist, J., & Imbens, G. (2002). Instrumental variables estimates of the effect of subsidized training on the quantiles of trainee earnings. Econometrica, 70(1), 91–117.

Abadie, A., Drukker, D., Herr, J. L., & Imbens, G. W. (2004). Implementing matching estimators for average treatment effects in Stata. The Stata Journal, 4(3), 290–311.

Acs, Z. J., Armington, C., & Zhang, T. (2007). The determinants of new-firm survival across regional economies: The role of human capital stock and knowledge spillover. Papers in Regional Science, 86, 367–391.

Almus, M., & Nerlinger, E. A. (1999). Growth of new technology-based firms: Which factors matter? Small Business Economics, 13, 141–154.

Amaral, A., Baptista, R., & Lima, F. (2011). Serial entrepreneurship: Impact of human capital on time to re-entry. Small Business Economics, 37, 1–21.

Andersson, P., & Wadensjö, E. (2007). Do the unemployed become successful entrepreneurs? International Journal of Manpower, 28, 604–626.

Arauzo-Carod, J.-M., & Segarra-Blasco, A. (2005). The determinants of entry are not independent of start-up size: Some evidence from Spanish manufacturing. Review of Industrial Organization, 27(2), 147–165.

Astebro, T., & Bernhardt, I. (2005). The winner’s curse of human capital. Small Business Economics, 24, 63–78.

Audretsch, D. B. (1991). New-firm survival and the technological regime. Review of Economics and Statistics, 73, 441–450.

Audretsch, D. B., & Mahmood, T. (1995). New firm survival: New results using a hazard function. Review of Economics and Statistics, 77, 97–103.

Audretsch, D. B., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (1999a). Start up size and industrial dynamics: Some evidence from Italian manufacturing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 17, 965–983.

Audretsch, D. B., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (1999b). Does start up size influence the likelihood of survival? In D. Audretsch & R. Thurik (Eds.), Innovation, industry evolution and employment (pp. 280–296). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bamford, C. E., Dean, T. J., & Douglas, T. J. (2004). The temporal nature of growth determinants in new bank foundings: Implications for new venture research design. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 899–919.

Barkham, R. J. (1994). Entrepreneurial characteristics and the size of the new firm: A model and an econometric test. Small Business Economics, 6, 117–125.

Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 72, 551–559.

Buenstorf, G., & Klepper, S. (2009). Heritage and agglomeration: The Akron tyre cluster revisited. Economic Journal, 119, 705–733.

Cabral, L., & Mata, J. (2003). On the evolution of the firm size distribution: Facts and theory. American Economic Review, 93, 1075–1090.

Caliendo, M., & Kritikos, A. (2010). Start-ups by the unemployed: Characteristics, survival and direct employment effects. Small Business Economics, 35, 71–92.

Capelleras, J.-L., & Hoxha, D. (2010). Start-up size and subsequent firm growth in Kosova: The role of entrepreneurial and institutional factors. Post-Communist Economies, 22(3), 411–426.

Cassiman, B., & Veugelers, R. (2002). R&D cooperation and spillovers: Some empirical evidence from Belgium. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1169–1184.

Chlosta, S., Patzelt, H., Klein, S. B., & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics, 38, 121–138.

Coad, A. (2009). The growth of firms: A survey of theories and empirical evidence. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Coad, A., Frankish, F., Roberts, R. G., & Storey, D. J. (2013). Growth paths and survival chances: An application of Gambler’s ruin theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 615–632.

Colombo, M. G., Delmastro, M., & Grilli, L. (2004). Entrepreneurs’ human capital and the start-up size of new technology-based firms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 22, 1183–1211.

Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2005). Start-up size: The role of external financing. Economics Letters, 88, 243–250.

Colombo, M. G., Giannangeli, S., & Grilli, L. (2013). Public subsidies and the employment growth of high-tech start-ups: Assessing the impact of selective and automatic support schemes. Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(5), 1273–1314.

Da Rin, M., Di Giacomo, M., & Sembenelli, A. (2010). Corporate taxation and the size of new firms: Evidence from Europe. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(2–3), 606–616.

Dahl, M. S., & Sorenson, O. (2012). Home sweet home: Entrepreneurs’ location choices and the performance of their ventures. Management Science, 58(6), 1059–1071.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 301–331.

Deaton, A. (2010). Instruments, randomization, and learning about development. Journal of Economic Literature, 48, 424–455.

Fairlie, R. W., & Robb, A. M. (2007). Why are black-owned businesses less successful than white-owned businesses? The role of families, inheritances, and business human capital. Journal of Labor Economics, 25(2), 289–323.

Firpo, S. (2007). Efficient semiparametric estimation of quantile treatment effects. Econometrica, 75(1), 259–276.

Frankish, J., Roberts, R., Coad, A., Spears, T., & Storey, D. J. (2013). Do entrepreneurs really learn? Or do they just tell us that they do? Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(1), 73–106.

Frolich, M., & Melly, B. (2008). “Unconditional quantile treatment effects under endogeneity.” IZA Bonn, Discussion paper 3288, January.

Frolich, M., & Melly, B. (2010). Estimation of quantile treatment effects with Stata. Stata Journal, 10(3), 423–457.

Geroski, P. A. (1995). What do we know about entry? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13, 421–440.

Geroski, P. A. (2000). The growth of firms in theory and in practice. In N. Foss & V. Mahnke (Eds.), Competence, governance and entrepreneurship (pp. 168–186). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Geroski, P. A., Mata, J., & Portugal, P. (2010). Founding conditions and the survival of new firms. Strategic Management Journal, 31, 510–529.

Gibrat, R. (1931). Les Inégalités Économiques: Applications, aux Inégalités des Richesses, à la Concentration des Entreprises, aux Populations des Villes, aux Statistiques des Familles, etc.: d’une Loi Nouvelle: la Loi de l’effet Proportionnel. Paris: Recueil Sirey.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., & Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750–783.

Girma, S., Gorg, H., Hanley, A., & Strobl, E. (2010). The effect of grant receipt on start-up size: Evidence from plant-level data. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 8, 371–391.

Gorg, H., Strobl, E., & Ruane, F. (2000). Determinants of firm start-up size: An application of quantile regression for Ireland. Small Business Economics, 14, 211–222.

Gottschalk, S., Greene, F. J., Höwer, D., & Müller, B. (2013). If you don’t succeed, should you try again? The role of entrepreneurial experience in venture survival. Mannheim: ZEW.

Hayward, M. L. A., Shepherd, D. A., & Griffin, D. (2006). A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Management Science, 52(2), 160–172.

Hvide, H. K., & Moen, J. (2010). Lean and hungry or fat and content? Entrepreneurs’ wealth and start-up performance. Management Science, 56(8), 1242–1258.

Ijiri, Y., & Simon, H. A. (1977). Skew distributions and the sizes of business firms. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670.

Klepper, S., & Sleeper, S. (2005). Entry by spinoffs. Management Science, 51(8), 1291–1306.

Koenker, R., & Hallock, K. F. (2001). Quantile regression. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 143–156.

Laspita, S., Breugst, N., Heblich, S., & Patzelt, H. (2012). Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 27, 414–435.

Leuven, E., & Sianesi, B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html. This version: version 4.0.4 Nov 10, 2010.

Levie, J. (2009). Enterprise in Scotland: Insights from global entrepreneurship monitor. Report for Scottish Enterprise: Research and Policy.

Levinthal, D. (1991). Random walks and organizational mortality. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 397–420.

Lotti, F., Santarelli, E., & Vivarelli, M. (2009). Defending Gibrat’s law as a long-run regularity. Small Business Economics, 32, 31–44.

Marlow, S., Mason, C., & Mullen, H. (2011). Advancing understanding of business closure and failure: A critical re-evaluation of the business exit decision. Paper presented at the 2011 ISBE conference, Sheffield, UK.

Mata, J. (1996). Markets, entrepreneurs and the size of new firms. Economics Letters, 52, 89–94.

Mata, J., & Machado, J. A. F. (1996). Firm start-up size: A conditional quantile approach. European Economic Review, 40, 1305–1323.

Mata, J., Portugal, P., & Guimaraes, P. (1995). The survival of new plants: Start-up conditions and post-entry evolution. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13, 459–482.

McKelvie, A., & Wiklund, J. (2010). Advancing firm growth research: A focus on growth mode instead of growth rate. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34, 261–288.

Melillo, F., Folta, T. B., & Delmar, F. (2012). What determines the initial size of new ventures? Mimeo, Copenhagen Business School, 5 September.

Metzger, G. (2006). “Once bitten twice shy?” The performance of entrepreneurial re-starts. Discussion Paper 06-083. Mannheim, Germany: ZEW.

Nielsen, K., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2011). Who re-enters entrepreneurship? And who ought to? An empirical study of success after failure. Paper presented at the EMAEE conference, February. Pisa, Italy.

Nurmi, S. (2006). Sectoral differences in plant start-up size in the Finnish economy. Small Business Economics, 26, 39–59.

Ongena, S., & Smith, D. C. (2000). What determines the number of bank relationships? Cross-country evidence. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 9(1), 26–56.

Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M., & Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review, 54, 442–454.

Politis, D. (2005). The process of entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 399–424.

Resende, M. (2007). Determinants of firm start-up size in the Brazilian industry: An empirical investigation. Applied Economics, 39, 1053–1058.

Robb, A., & Fairlie, R. W. (2009). Determinants of business success: An examination of Asian-owned business in the USA. Journal of Population Economics, 22, 827–858.

Roberts, P. W., Klepper, S., & Hayward, S. (2011). Founder backgrounds and the evolution of firm size. Industrial and Corporate Change, 20, 1515–1538.

Santarelli, E., Carree, M., & Verheul, I. (2009). Unemployment and firm entry and exit: An update on a controversial relationship. Regional Studies, 43, 1061–1073.

Staiger, D., & Stock, J. H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65, 557–586.

Storey, D. J. (2011). Optimism and chance: The elephants in the entrepreneurship room. International Small Business Journal, 29(4), 303–321.

Thurik, A. R. (2003). Entrepreneurship and unemployment in the UK. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 50, 264–290.

Wright, M., & Stigliani, I. (2013). Entrepreneurship and growth. International Small Business Journal, 31(1), 3–22.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Marco Capasso, Gianluca Capone, Giovanni Cerrulli, Alex McKelvie, Francesca Melillo, Puay Tang, Bram Timmermans and Bart Verspagen and seminar participants at INGENIO (Valencia), Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Reus) and the University of Maastricht and the 2012 Schumpeter Conference (Brisbane), as well as 2 anonymous referees, for many helpful comments. Any remaining errors, however, are ours alone. A.C. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the ESRC, TSB, BIS and NESTA on grants ES/H008705/1 and ES/J008427/1 as part of the IRC distributed projects initiative, as well as from the AHRC as part of the FUSE project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

J.S.F. and R.G.R. write only in a personal capacity and do not seek to represent the views of Barclays Bank. This paper includes references to analyses of Barclays customer records undertaken by the authors with the permission of the bank. All research was conducted in a manner consistent with data protection obligations. No personal details were released to individuals outside of the Barclays Group.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coad, A., Frankish, J.S., Nightingale, P. et al. Business experience and start-up size: Buying more lottery tickets next time around?. Small Bus Econ 43, 529–547 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9568-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9568-2