Abstract

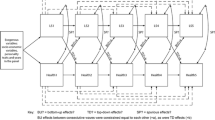

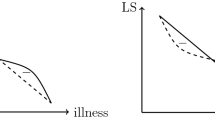

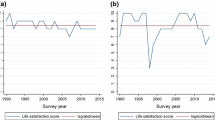

Long term panel data enable researchers to construct trajectories of life satisfaction (LS) for individuals over time. In this paper we analyse the trajectories of respondents (N = 3689) in the German Socio-Economic Panel who recorded their LS for 20 consecutive years in 1991–2010. Previous research has shown that at least a quarter of these respondents recorded substantial long term changes in LS (Headey et al. in Proc Natl Acad Sci 107.42:17922–17926, 2010a, in Soc Indic Res 112:725–748, 2013). In this paper, graphs of LS trajectories, and subsequent statistical analysis, show that respondents tend to spend multiple consecutive years above and, in other periods, below their own 20-year mean level of LS. They experience extended ‘good times’ and extended ‘bad times’. These results are contrary to set-point theory which views LS as stable, except for short term fluctuations due to life events. In the later part of the paper we attempt to move towards a theory of medium term life satisfaction. We estimate structural equation models with two-way causation between LS and variables usually treated as causes of LS, including health, physical exercise, frequency of social activities, and satisfaction with work and leisure. Results are interpreted as showing positive feedback loops between these variables and LS, accounting for extended periods of high or low LS. The models are based on a modified concept of ‘Granger-causation’ (Granger in Econometrica 37:424–438, 1969). The main intuition behind Granger-causation is that if x can be shown to be statistically significantly related to y in a model which includes multiple lags of y, then it can be inferred that x is one cause of y.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The sample size would have been almost halved to 1873 if the age restriction had not been lifted.

The correlation between these two items varies from year to year, but is usually around 0.3.

‘Seldom’ or ‘never’ have been included as separate categories in more recent waves of SOEP.

Disability status was not included in models in which the self-rated health scale was the x variable.

The Big Five items have been included in SOEP every 4 years since 2005. In the case of respondents who have answered more than once, we have averaged their results and imputed the average for missing years. So we treat adult personality traits as fixed characteristics, as most psychologists would.

OLS regression analysis is essentially a single equation technique. Regression estimates derived from multi-equation systems are likely to be biased, due to correlations between explanatory variables and error terms in some or all equations. A key assumption of OLS regression is that such correlations are zero.

ML estimates are usually consistent and asymptotically normal under the (not very restrictive) assumption of conditional normality (StataCorp 2013). Only paths or covariances linking conditioning (i.e. control) variables may not be consistent and asymptotically normal (even then, the main problem lies just with estimates of standard errors). These paths are not usually of substantive interest. Substantive interest lies in paths (1) linking exogenous with endogenous variables and (2) between endogenous variables.

From a mathematical standpoint, a model can be viewed as a set of constraints—or a set of restricted paths—limiting the possibilities of simply reproducing the input data. Attempts by a researcher to improve his/her model involve modifying these constraints to improve model fit…subject to the theory/hypotheses underlying the model.

Model ‘stability’ is here used as a technical term. Previously we used the term in a different sense to refer to Scherpenzeel and Saris’s (1996) claim that two-way causation models of LS are unstable because apparently small differences in model specification can lead to substantially different estimates.

Another limitation is that covariances between the error terms of equations cannot be estimated, so it becomes difficult to assess whether relationships are spurious.

When convergence fails, exactly the same Chi square LR is produced repeatedly, model iteration after iteration.

Kessler and Greenberg (1981) describe how a multi-wave panel model of this kind may in principle be identified by using equality constraints (i.e. by constraining sets of parameters to be equal to each other). In practice, this approach to identification only succeeds if relationships among variables are quite far from equilibrium (i.e. relationships differ substantially from wave to wave of the panel data). In panel surveys of life satisfaction, it is reasonably clear that relationships between LS and causal variables of interest are much the same from wave to wave. Estimation of models with both simultaneous and cross-lagged links is also likely to run into problems because of multicollinearity; the effects on LS of x at time t and x at t − 1 are likely to be too highly correlated for estimates to be reliable.

It is accepted, of course, that differing 20-year trajectories can have the same mean and standard deviation. Our inspection of a very large number of trajectories indicated that few panel members recorded steady 20-year declines or steady increases in LS. The majority recorded trajectories with multi-year periods of both relatively high and relatively low LS, as shown in Figs. 2b, d, f. The statistical analysis below (Table 1) confirms this point.

Another way of making the same point: among individuals who were above their own 1991–2010 grand mean of LS in any particular year, just over 25 % remained above it for all of the next four years. By chance only 6.25 % would have done so.

With a large sample size, it is obvious that many statistically significant but substantively trivial effects are likely to be found.

In the final run of this model the equality constraints on the BU and TD estimates for the equations for Exerciset+1 and LSt+1 were dropped. The reason is that these are not ‘Granger’ equations in that no ‘extra’ (2nd, 3rd) lags are available. Consequently, as Granger would predict, the estimates of the BU and TD links from these equations are considerably higher than from the equations with multiple lags, and are probably biased (Granger and Newbold 1974).

Results for sub-sets of the population are not printed here; available from the authors.

Again, no statistically significant differences were found between men and women, or older and younger people.

As was the case for some of the models with only one x variable, just one pair of imposed equality constraints in this multivariate model was diagnosed as not strictly justified; the LR test result would be improved if they were dropped. Again, however, the measures of fit which reward parsimony—the TLI and RMSEA—provide countervailing evidence in favour of retaining the constraints.

References

Allison, P. D. (2005). Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (2011). Modelling dynamics in time-series cross-section political economy data. Annual Review of Political Science, 14, 331–352.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bentler, P. M., & Freeman, E. H. (1983). Tests for stability in linear structural equation systems, Psychometrika, 48, 143–145.

Bollen, K. A. (2010). A general panel model with random and fixed effects: A structural equation approach. Social Forces, 89, 1–34.

Brickman, P. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation level theory (pp. 287–302). New York: Academic Press.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Coleman, J. S. (1968). The mathematical study of change. In H. Blalock & A. Blalock (Eds.), Methodology in social research (pp. 428–478). New York: McGraw Hill.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influences of extroversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 668–678.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1991). NEO PI-R. Odessa, FL: PAR.

Deeg, D., & van Zonneveld, R. J. (1989). Does happiness lengthen life? In R. Veenhoven (Ed.), How harmful is happiness? (pp. 29–43). Rotterdam: Erasmus University Press.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 1–31.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 25, 276–302.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth (pp. 89–125). New York: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100.19, 11176–11183. doi:10.1073/pnas.1633144100.

Easterlin, R. A., & Angelescu, L. (2009). Happiness and growth the world over: Time series evidence on the happiness-income paradox. Discussion paper no. 4060 (Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn). Available at http://ftp.iza.org/dp4060.pdf

Finkel, S. E. (1995). Causal analysis with panel data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 402–435.

Frick, J. R., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2007). Enhancing the power of the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP)—Evolution, scope and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch, 127, 139–169.

Fujita, F., & Diener, E. (2005). Life satisfaction set-point: Stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 158–164.

Granger, C. W. J. (1969). Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, 37, 424–438.

Granger, C. W. J., & Newbold, P. (1974). Spurious regressions in econometrics. Journal of Econometrics, 2(2), 111–120.

Greenberg, D. F., & Kessler, R. C. (1982). Equilibrium and identification in linear panel models. Sociological Research and Methods, 10, 435–451.

Gremeaux, V., Gayda, M., Lepers, R., Sosner, P., Juneau, M., & Nigam, A. (2012). Exercise and longevity. Maturitas, 73, 312–317.

Headey, B. W. (2008a). The set-point theory of well-being: Negative results and consequent revisions. Social Indicators Research, 85, 389–403.

Headey, B. W. (2008b). Life goals matter to happiness: A revision of set-point theory. Social Indicators Research, 86, 213–231.

Headey, B. W., Hoehne, G., & Wagner, G. G. (2014). Does religion make you healthier and longer lived? Evidence for Germany, Social Indicators Research, 119, 1335–1361.

Headey, B. W., Muffels, R. J. A., & Wagner, G. G. (2010a). Long-running German panel survey shows that personal and economic choices, not just genes, matter for happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(42), 17922–17926.

Headey, B. W., Muffels, R. J. A., & Wagner, G. G. (2013). Choices which change life satisfaction: Similar results for Australia. Britain and Germany, Social Indicators Research, 112, 725–748.

Headey, B. W., Schupp, J., Tucci, I., & Wagner, G. G. (2010b). Authentic happiness theory supported by impact of religion on life satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis with data for Germany. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 73–82.

Headey, B. W., Veenhoven, R., & Wearing, A. J. (1991). Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 24, 81–100.

Kessler, R. C., & Greenberg, D. F. (1981). Linear panel analysis. New York: Academic Press.

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lucas, R. E. (2008). Personality and subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 171–194). New York: Guilford Press.

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Reexamining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: Reactions to change in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 527–539.

Luhmann, M., & Eid, M. (2009). Does it really feel the same? Changes in life satisfaction following repeated life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 363–381.

Luhmann, M., Hoffman, W., Eid, M., & Lucas, R. E. (2012). Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 592–615.

Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7, 186–189.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111–131.

Mackay, L. M., Oliver, M., & Schofield, G. M. (2011). Demographic variations in discrepancies between objective and subjective measures of physical activity. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1, 13–19. Available at http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPM/

Mathison, L., Andersen, M. H., Veenstra, M., Wahl, A. K., Hanestad, B. R., & Fosse, E. (2007). Quality of life can both influence and be an outcome of general health perceptions after heart surgery. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 27. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-5-27.

Mehnert, T., Kraus, H. H., Nadler, R., & Boyd, M. (1990). Correlates of life satisfaction in those with a disabling condition. Rehabilitation Psychology, 35, 3–17.

Meier, S., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Is volunteering rewarding in itself? IZA discussion paper no. 1045, IZA, Bonn.

Nagazato, N., Schimmack, U., & Oishi, S. (2011). Effect of changes in living conditions on well-being: A prospective top-down bottom-up model. Social Indicators Research, 100, 115–135.

Nickerson, C., Schwarz, N., Diener, E., & Kahneman, D. (2003). Zeroing in on the dark side of the American dream: A closer look at the negative consequences of the goal for financial success. Psychological Science, 14, 531–536.

Pearl, J. (2009). Causality: Models, reasoning and inference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scherpenzeel, A., & Saris, W. E. (1996). Causal direction in a model of life satisfaction: The top-down/bottom-up controversy. Social Indicators Research, 38, 161–180.

Schwarze, J., Andersen, H., & Silke, A. (2000). Self-assessed health and changes in self-assessed health as predictors of mortality—First evidence from the German panel data. DIW discussion paper no. 203, Berlin, DIW.

Sheldon, K. M., & Lucas, R. E. (Eds.). (2014). The stability of happiness. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

StataCorp. (2013). Structural equation modelling reference manual, release 13. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 39, 1–102.

Tuma, N., & Hannan, M. (1984). Social dynamics. New York: Academic Press.

Wilkins, A. S. (2014). To lag or not to lag: Re-evaluating the use of lagged dependent variables in regression analysis. Working paper, Stanford University Department of Political Science. Downloaded July 4, 2014.

Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, T. D. (2008). Explaining away: A model of affective adaptation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 370–386.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Headey, B., Muffels, R. Towards a Theory of Medium Term Life Satisfaction: Two-Way Causation Partly Explains Persistent Satisfaction or Dissatisfaction. Soc Indic Res 129, 937–960 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1146-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1146-8