Abstract

This paper explores and defends the idea that mental properties and their physical bases jointly cause their physical effects. The paper evaluates the view as an emergentist response to the exclusion problem, comparing it with a competing nonreductive physicalist solution, the compatibilist solution, and argues that the joint causation view is more defensible than commonly supposed. Specifically, the paper distinguishes two theses of closure, Strong Closure and Weak Closure, two causal exclusion problems, the overdetermination problem and the supervenience problem, and argues that emergentists can avoid the overdetermination problem by denying Strong Closure and respond to the supervenience problem by accepting the joint causation view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Bennett’s (2003, 2008) strategy is to give a counterfactual test for overdetermination and use it to argue that mental and physical causes can be distinct and sufficient causes without overdetermining their effects. She argues that, on nonreductive physicalism, mental and physical causes are too tightly connected to meet her counterfactual test.

There is a question of whether metaphysical supervenience is sufficient to capture the physicalist idea of “nothing over and above” (e.g. Horgan 1993; Wilson 2005; Polger 2013; Morris 2018), but it is generally agreed that physicalism at least requires metaphysical supervenience. Following Jackson (1998) and Lewis (1983), I’ll understand physicalism as the thesis that any minimal physical duplicate of this world is a duplicate simpliciter.

‘Emergentism’ has been used to express a variety of views. Some emergentists endorse metaphysical supervenience (e.g. Wilson 2015), not just nomological supervenience, and some reject synchronic supervenience, taking emergence to be diachronic (e.g. Humphreys 1997, O’Connor and Wong 2005). Throughout I will be using ‘emergentism’ and ‘nonreductive physicalism’ simply as labels for the positions characterized above. My characterization of emergentism corresponds to what Horgan (2006) calls ‘standard emergentism.’ Others who distinguish emergentism and nonreductive physicalism in terms of metaphysical/nomological supervenience include Van Cleve (1990), Chalmers (2006), Bennett (2008), Noordhof (2010).

Arguably, the compatibilist strategy is not an essentially nonreductive physicalist one. Bennett (2008) argues that the compatibilist strategy, at least her own version, works only for nonreductive physicalism. But it might be available to emergentists as well. It might be argued that mental and physical causes do not causally compete, or really overdetermine their effects, because they are lawfully linked, and that the mental-physical case differs from paradigm cases of overdetermination. Here I focus only on the nonreductive physicalist version of compatibilism.

Alexander (1920) equates the reality of an entity with its having causal powers. The idea goes back to Plato in the Sophist (247e).

Although I describe the joint causation view using counterfactuals, it does not mean that the view is committed to a counterfactual account of causation or any particular conception of cause. I’m just relying on an intuitive and ordinary understanding of causation. We have a perfectly clear intuition about the difference between, say, standard firing squad cases and cases where each cause is necessary for the effects. My only assumption is that, unlike overdetermination cases, joint causation cases will satisfy (i) and (ii). It might turn out, of course, that joint causation claims presuppose a particular conception of cause, but that is something that needs to be shown. Thanks to a referee for raising this issue.

It may be wondered whether the joint causation view is an essentially emergentist view. One might wonder, for instance, whether those who accept metaphysical supervenience (e.g. Wilson 2015) can accept the joint causation view. This is a debatable question. Here I focus on the emergentist version of the joint causation view, which holds that (i) and (ii) are nonvacuously true.

In giving an illuminating discussion of British emergentism, McLaughlin (1992) introduces the notion of configurational force to make sense of downward causation. He observes that configurational forces are not incompatible with the laws of (classical or quantum) mechanics, nor with relativity theory, but notes that the British emergentists offered “not a scintilla of evidence” that such configurational forces exist (1992, 55), concluding that their downfall was due to empirical, rather than a priori philosophical, reasons. I agree with almost all of what he says, but I think he fails to fully appreciate the challenge to emergentism’s internal coherence, related to what I call the “supervenience problem.”

Two clarifications. First, instead of positing the yellow-force, one might want to modify, or supplement, the law of gravitation to explain the motion of particles. I briefly discuss this and related issues in Sect. 5. Second, if emergents are fundamental, as a referee points out, one might wonder why they do not count as physical. Indeed, if the scenario above turns out to be actual, mental properties, or the configurational mental forces, might be incorporated into the physical, just as the concept of ‘physical’ was extended to accommodate electromagnetic phenomena. (From this some have suggested that physicalism is trivial or lacks a determinate content; see, e.g., Hempel 1969; Chomsky 1972; Crane and Mellor 1990.) This, however, does not trivialize emergentism. There is a substantive issue whether mental properties as we now understand them need to be added as the basic constituents of the world. What counts as physical is an important issue, but we need not answer it here to present the central ideas of emergence and the joint causation view.

In an indeterministic world, it needs to be reformulated: the probabilities of all physical events are fully determined by law by prior physical conditions. Nothing significant in my discussion hinges on the deterministic assumption.

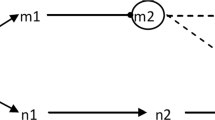

Here and below I have simplified Lowe’s claims and altered the event labels to make them fit Fig. 1.

Sober makes this point in assessing the evidential status of physicalism and supervenience.

Poland too makes this point in the context of evaluating physicalism rather than physical causal closure. He identifies and discusses some general issues concerning what kinds of evidence or argument would provide an evidential basis for the confirmation or disconfirmation of physicalism.

Even this is not uncontroversial. Cartwright (1999), for example, argues that even the fundamental laws of physics are incomplete in that they work only for very simple systems under very stringent ceteris paribus conditions. Hendry (2006) argues that physical causal closure is not so well established in chemistry. See also Dupré (1993).

Lowe (2000) and Yates (2009) distinguish various versions of causal closure and discuss some epistemic issues concerning their evidential status. Silberstein (2006) and Wilson (2015), unlike Lowe and Yates, do not accept nomological supervenience. While Wilson (2015) accepts metaphysical supervenience, Silberstein (2006) even denies nomological supervenience; he says that “mental properties are not even fully nomologically determined by fundamental physical properties and laws” (2006, pp. 204–5).

The “job opening” metaphor is from Bennett (2008, p. 281, fn. 4).

Kim sometimes makes a distinction between the “exclusion argument” and the “supervenience argument” (e.g., 2011, pp. 214–220): the exclusion argument purports to show that mental-to-physical causation is problematic, while the supervenience argument purports to show that mental-to-mental causation presupposes mental-to-physical causation. So the supervenience argument rests on the exclusion argument and extends its reach to also challenge mental-to-mental causation (e.g., Bennett 2008, p. 300). On my distinction, both the overdetermination and supervenience problems concern mental-to-physical causation but differ in their sources: one is generated by causal closure and the other by supervenience.

For instance, she might want to adopt “interventionist” attempts recently proposed by some (e.g. Woodward 2008; List and Menzies 2009). Those proposals are best viewed as attempts to solve the supervenience problem, leaving the overdetermination problem untouched; they argue that for some effects, supervenient causes should be expected to be in some sense better causes than their subvenient bases. One interesting issue is whether the nonreductive physicalist’s seemingly best strategy for solving the overdetermination problem, the compatibilist strategy, is compatible with her seemingly best strategy for solving the supervenience problem, the interventionist strategy. (I think there is reason to suspect that they are not compatible.) There is also the question whether the interventionist strategy is an essentially nonreductive physicalist one.

Though the expression ‘full’ in his ‘a full cause’ suggests otherwise.

Compare Bennett (2003, p. 472): Focusing solely upon the overdetermination problem, Bennett observes a similar tension between the overdetermination problem and other mental causation problems, problems that arise from the natures of mind, like extrinsicness, anomality, etc. The tension I’m pointing out is within the exclusion problem.

References

Alexander, S. (1920). Space, time, and deity (Vol. 2). London: Macmillan.

Bennett, K. (2003). Why the exclusion problem seems intractable, and how, just maybe, to tract it. Noûs, 37, 471–497.

Bennett, K. (2008). Exclusion again. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced (pp. 280–305). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bishop, R. (2006). The hidden premise in the causal argument for physicalism. Analysis, 66, 44–52.

Broad, C. D. (1923). Mind and its place in nature. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Cartwright, N. (1999). The dappled world: A study of the boundaries of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chalmers, D. (1996). The conscious mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chalmers, D. (2006). Strong and weak emergence. In P. Clayton & P. Davies (Eds.), The re-emergence of emergence (pp. 244–254). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chalmers, D. (2007). Naturalistic dualism. In M. Velmans & S. Schneider (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to consciousness (pp. 359–368). Oxford: Blackwell.

Chomsky, N. (1972). Language and mind. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Crane, T. (2001). The significance of emergence. In C. Gillett & B. Loewer (Eds.), Physicalism and its discontents (pp. 207–224). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crane, T., & Mellor, D. H. (1990). There is no question of physicalism. Mind, 99, 185–206.

Dupré, J. (1993). The disorder of things. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Fodor, J. (1990). Making mind matter more. A theory of content and other essays. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gillett, C. (2010). On the implications of scientific composition and completeness. In A. Corradini & T. O’Connor (Eds.), Emergence in science and philosophy (pp. 25–45). London: Routledge.

Hempel, C. (1969). Reduction: Ontological and linguistic facets. In S. Morgenbesser, et al. (Eds.), Philosophy, science, and method: Essays in honor of Ernest Nagel. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hendry, R. F. (2006). Is there downward causation in chemistry? In D. Baird, E. Scerri & L. McIntyre (Eds.), Philosophy of chemistry: Synthesis of a new discipline (pp. 173–189). Dordrecht: Springer.

Horgan, T. (1993). From supervenience to superdupervenience: Meeting the demands of a material world. Mind, 102, 555–586.

Horgan, T. (1997). Kim on mental causation and causal exclusion. Philosophical Perspectives, 11, 165–184.

Horgan, T. (2006). Materialism: Matters of definition, defense, and deconstruction. Philosophical Studies, 131, 157–183.

Humphrey, P. (1997). How properties emerge. Philosophy of Science, 64, 1–17.

Jackson, F. (1982). Epiphenomenal qualia. Philosophical Quarterly, 32, 127–136.

Jackson, F. (1998). From metaphysics to ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kim, J. (1992). Downward causation’ in emergentism and nonreductive physicalism. In A. Beckermann, H. Flohr, & J. Kim (Eds.), Emergence or reduction? (pp. 119–138). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Kim, J. (1993). The nonreductivist’s troubles with mental causation. In his Supervenience and mind (pp. 309–335). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world. Cambridge, MA: Bradford.

Kim, J. (1999). Making sense of emergence. Reprinted in his Essays in the metaphysics of mind (pp. 8–40). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kim, J. (2005). Physicalism, or something near enough. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kim, J. (2006). Emergence: Core ideas and issues. Reprinted in his Essays in the metaphysics of mind (pp. 66–84). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kim, J. (2011). Philosophy of mind (3rd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview press.

Kripke, S. (1980). Naming and necessity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1983). New work for a theory of universals. Reprinted in his Papers in metaphysics and epistemology (pp. 8–55). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. (1988). What experiences teaches. Reprinted in his Papers in metaphysics and epistemology (pp. 262–290). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

List, C., & Menzies, P. (2009). Nonreductive physicalism and the limits of the exclusion principle. Journal of Philosophy, 106, 475–502.

Loewer, B. (2002). Comments on Jaegwon Kim’s Mind in a physical world. Philosophy and Phenomenal Research, 65, 655–663.

Lowe, E. J. (2000). Causal closure principles and emergentism. Reprinted in his Personal agency (pp. 41–57). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lowe, E. J. (2003). Physical causal closure and the invisibility of mental causation. Reprinted in his Personal agency (pp. 58–78). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McLaughlin, B. (1992). The rise and fall of British emergentism. In A. Beckermann, H. Flohr & J. Kim (Eds.) Emergence or reduction? (pp. 49–93). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Morgan, C. L. (1923). Emergent evolution. London: William & Norgate.

Morris, K. (2018). What’s wrong with Brute supervenience? Analytic Philosophy, 59, 256–280.

Noordhof, P. (2010). Emergent causation and property causation. In C. Macdonald & G. Macdonald (Eds.), Emergence in mind (pp. 69–99). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Connor, T. (2000). Persons and causes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Connor, T., & Wong, H. Y. (2005). The metaphysics of emergence. Noûs, 39, 658–678.

Papineau, D. (2001). The rise of physicalism. In C. Gillett & B. Loewer (Eds.), Physicalism and its discontents (pp. 3–36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Papineau, D. (2008). Must a physicalist be a microphysicalist? In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced (pp. 126–148). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Papineau, D. (2009). The causal closure of the physical and naturalism. In B. McLaughlin (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of philosophy of mind (pp. 53–65). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pereboom, D. (2002). Robust nonreductive materialism. Journal of Philosophy, 99, 499–531.

Poland, J. (1994). Physicalism: The philosophical foundations. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Polger, T. (2013). Physicalism and moorean supervenience. Analytic Philosophy, 54, 72–92.

Schaffer, J. (2003). Overdetermining causes. Philosophical Studies, 114, 23–45.

Shoemaker, S. (2001). Realization and mental causation. In C. Gillett & B. Loewer (Eds.), Physicalism and its discontents (pp. 74–98). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sider, T. (2003). What’s so bad about overdetermination? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 67, 719–726.

Silberstein, M. (2006). In defense of ontological supervenience and mental causation. In P. Clayton & P. Davies (Eds.), The re-emergence of emergence (pp. 203–226). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sober, E. (1999). Physicalism from a probabilistic point of view. Philosophical Studies, 95, 135–174.

Van Cleve, J. (1990). Mind-dust or magic? panpsychism versus emergence. Philosophical Perspective, 4, 215–226.

Wilson, J. (2005). Supervenience-based characterizations of physicalism. Noûs, 39, 426–459.

Wilson, J. (2015). Metaphysical emergence: Weak and strong. In T. Bigaj & C. Wüthrich (Eds.) Metaphysics in contemporary physics (pp. 251–306). Leiden: Brill.

Won, C. (2014). Overdetermination, counterfactuals, and mental causation. Philosophical Review, 123, 205–229.

Woodward, J. (2008). Mental causation and neural mechanism. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced (pp. 218–262). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yablo, S. (1992). Mental causation. Philosophical Review, 101, 245–280.

Yates, D. (2009). Emergence, downwards causation and the completeness of physics. Philosophical Quarterly, 59, 110–131.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Jaegwon Kim, Derek Bowman, and Kevin Morris for detailed written comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Thanks also to David Christensen, Sungil Han, Sungsu Kim, Doug Kutach, Hongwoo Kwon, Josh Schechter, and the anonymous referees for helpful comments and discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Won, C. Mental causation as joint causation. Synthese 198, 4917–4937 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02378-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02378-4