Abstract

Objectives

Using data from a randomized experiment, to examine whether moving youth out of areas of concentrated poverty, where a disproportionate amount of crime occurs, prevents involvement in crime.

Methods

We draw on new administrative data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment. MTO families were randomized into an experimental group offered a housing voucher that could only be used to move to a low-poverty neighborhood, a Section 8 housing group offered a standard housing voucher, and a control group. This paper focuses on MTO youth ages 15–25 in 2001 (n = 4,643) and analyzes intention to treat effects on neighborhood characteristics and criminal behavior (number of violent- and property-crime arrests) through 10 years after randomization.

Results

We find the offer of a housing voucher generates large improvements in neighborhood conditions that attenuate over time and initially generates substantial reductions in violent-crime arrests and sizable increases in property-crime arrests for experimental group males. The crime effects attenuate over time along with differences in neighborhood conditions.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that criminal behavior is more strongly related to current neighborhood conditions (situational neighborhood effects) than to past neighborhood conditions (developmental neighborhood effects). The MTO design makes it difficult to determine which specific neighborhood characteristics are most important for criminal behavior. Our administrative data analyses could be affected by differences across areas in the likelihood that a crime results in an arrest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Other studies of data from the long-term MTO follow-up find beneficial effects on adult physical health, specifically extreme obesity and diabetes (Ludwig et al. 2011) and on adult subjective well-being (Ludwig et al. 2012). See Sanbonmatsu et al. (2011) and Ludwig et al. (2013) for summaries of long-term MTO findings.

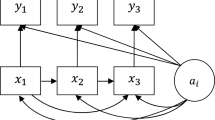

Consider a model in which criminal behavior in time period T, YT, is potentially affected by someone’s entire accumulated history of exposure to different neighborhood conditions: YT = f(XT, XT-1, …, X0). Criminal behavior could be affected by neighborhood conditions in time T, XT (“situational neighborhood effects”) and/or by neighborhood conditions in some previous period, XT-K (“developmental neighborhood effects”).

Olsen (2003, pp. 365–441) provides an excellent review of the housing voucher program, which provides families with a subsidy to live in private-market housing. The maximum voucher subsidy is determined by the Fair Market Rent (FMR), which is a function of family size, the gender mix of adults and children in the home, and the local rent distribution. For a family of four, the FMR is between 40 and 50 % of the local metropolitan area private-market rent distribution. For example, the FMR for a two-bedroom apartment in the Chicago area was equal to $699 in 1994, $732 in 1997, and $762 in 2000. Families are expected to pay 30 % of their income (adjusted by family size, childcare expenses and medical expenses) towards their rent. Note that, in the United States, housing assistance is not an entitlement, so housing voucher (and other housing) programs usually have long wait lists. Olsen estimates that only around 28 % of income-eligible families in the U.S. receive any housing assistance.

Another difference between the present study and Kling et al. (2005) is that the interim study counted by quarter from the specific date of random assignment whereas in our study we set the quarter of random assignment to “quarter 0” and the next calendar quarter to “quarter 1”.

We also present estimates of treatment effects on a broader range of neighborhood characteristics averaged (using duration weights) across all addresses between random assignment and May 31, 2008, just prior to the start of the MTO long-term survey fielding period.

The offer of a housing voucher in MTO is the chance to move to a new neighborhood characterized by a range of different socio-demographic, physical, and other features. As discussed below, MTO is less informative about the causal effects of particular elements within the bundle of neighborhood characteristics that change via MTO moves, but it does provide very strong grounds for inference about the causal effects of changing that bundle of neighborhood features.

The experimental group impacts from the models limited to (1) the youth for whom we have fairly complete address information via address updates from the adult long-term survey interview (the proxy address sample), and (2) the youth who were still living with the adult as of the long-term survey are very similar to those for the main sample. But the Section 8 results are less robust across specifications, particularly in later years. However, because for cost reasons we sought interviews with only a random two-thirds of adults from Section 8 households, these restricted analysis samples are rather small, leading to power concerns. Furthermore, the results from the specification where we extrapolate from the youth’s address at age 18 demonstrate the importance of tracking the youth over time because the effects of MTO on neighborhood characteristics, especially for females, appear stronger in these models than they do in the unadjusted results and the two other alternative specifications. Because the address at 18 is more likely to have been the home of the household head, it appears that the youth were leaving home and moving to somewhat worse neighborhoods than where their parents lived.

The results presented here differ slightly from those presented in Kling et al. (2005) because we resubmitted the identifying information for these youth to the criminal justice agencies to match again from scratch, and the matching procedures used by the agencies changed slightly from when these identifiers were submitted for matching for the interim (4- to 7-year) MTO study. We rely on the data we received back for the long-term MTO study match so that we can consistently examine how MTO impacts on arrests evolve over time.

References

Angrist, J. D., Imbens, G. W., & Rubin, D. B. (1996). Identification of Causal Effects Using Instrumental Variables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91(434), 444–455.

Becker, G. S., & Murphy, K. M. (2000). Social Economics: Market Behavior in a Social Environment (Vol. 2, p. 170). Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Bellair, P. E. (2000). Informal Surveillance And Street Crime : A Complex Relationship. Criminology, 38(1), 137–170.

Beyers, J. M., Loeber, R., Wikström, P.-O. H., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2001). What predicts adolescent violence in better-off neighborhoods? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(5), 369–381.

Bloom, H. S. (1984). Accounting for No-Shows in Experimental Evaluation Designs. Evaluation Review, 8(2), 225–246.

Borjas, G. J. (1995). Ethnicity, neighborhoods and human-capital externalities. American Economic Review, 85(3), 365–390.

Brock, W. A., & Durlauf, S. N. (2001). Interactions-Based Models. In J. J. Heckman & E. E. Leamer (Eds.), Handbook of Econometrics (Vol. 5, pp. 3297–3380). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G. J., Klebanov, P. K., & Sealand, N. (1993). Do Neighborhoods Influence Child and Adolescent Development? American Journal of Sociology, 99(2), 353–395.

Case, A. C., & Katz, L. F. (1991). The Company You Keep: The Effects of Family and Neighborhood on Disadvantaged Youths. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 3705.

Clarke, R. V. (1995). Situational Crime Prevention: Achievements and Challenges. In M. H. Tonry & D. R. Farrington (Eds.), Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime Prevention (Vol. 19, pp. 91–150). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. (E. L. Lesser, Ed.)American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

Cook, P. J., & Goss, K. (1996). A selective review of the social-contagion literature. Working Paper: Sanford Institute of Public Policy, Duke University.

Cook, T. D., Shadish, W. R., & Wong, V. C. (2008). Three Conditions under Which Experiments and Observational Studies Produce Comparable Causal Estimates : New Findings from Within-Study Comparisons Abstract. Policy Analysis, 27(4), 724–750.

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (2003). Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: a reply to Wortley’s critique of situational crime prevention. Crime Prevention Studies, 16, 41–96.

Crane, J. (1991). The Epidemic Theory of Ghettos and Neighborhood Effects on Dropping Out and Teenage Childbearing. American Journal of Sociology, 96(5), 1226–1259.

Esbensen, F.-A., & Huizinga, D. (1990). Community Structure and Drug Use: From a Social Disorganization Perspective. Justice Quarterly, 7(4), 691–709.

Furstenberg, F. F., Cook, T. D., Eccles, J., & Elder, G. H. (1999). Managing to make it: Urban families in high-risk neighborhoods. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gaviria, A., & Raphael, S. (2001). School-Based Peer Effects and Juvenile Behavior. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(2), 257–268.

Gebler, N., Gennetian, L. A., Hudson, M. L., Ward, B., & Sciandra, M. (2012). Achieving MTO’s High Effective Response Rates: Strategies and Tradeoffs. Cityscape, 14(2), 57–86.

Glaeser, E. L., & Scheinkman, J. A. (1999). Measuring social interactions. Unpublished paper, Harvard University.

Glaeser, E. L., Sacerdote, B., & Scheinkman, J. A. (1996). Crime and Social Interactions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(2), 507–548.

Goering, J., Kraft, J., Feins, J. D., McInnis, D., Holin, M. J., & Elhassan, H. (1999). Moving to Opportunity for fair housing demonstration program: Current status and initial findings. Washington: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A General Theory of Crime. (F. Cullen & R. Agnew, Eds.)Criminological theory Past to present (Vol. 34, p. 324). Stanford University Press.

Groves, R. M., Fowler, F. J., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., & Singer, E. (2004). Survey Methodology (7th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Heller, S., Pollack, H. F., Ander, R., & Ludwig, J. (2013). Preventing Youth Violence and Dropout: A Randomized Field Experiment. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 19014.

Hirschfield, A., & Bowers, K. (1997). The Development of a Social, Demographic and Land Use Profiler for Areas of High Crime. British Journal of Criminology, 37(1), 103–120.

Hogan, D. P., & Kitagawa, E. M. (1985). The impact of social status, family structure, and neighborhood on the fertility of Black adolescents. American Journal of Sociology, 90(4), 825–855.

Hogan, D. P., Astone, N. M., & Kitagawa, E. M. (1985). Social and Environmental Factors Influencing Contraceptive Use Among Black Adolescents. Family Planning Perspectives, 17(4), 165–169.

Homel, R., & Clarke, R. V. (1997). A revised classification of situational crime prevention techniques. In S. P. Lab (Ed.), Crime Prevention at a Crossroads (pp. 17–27). Cincinnati: Anderson.

Huizinga, D., Thornberry, T. P., Knight, K. E., Lovegrove, P. J., Loeber, R., Hill, K., & Farrington, D. R. (2007). Disproportionate Minority Contact in the Juvenile Justice System: A Study of Differential Minority Arrest/Referral to Court in Three Cities. Washington: U.S. Department of Juvenile Justice.

Jencks, C., & Mayer, S. E. (1990). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In L. Lynn & M. McGeary (Eds.), Inner-City Poverty in the United States (pp. 111–186). Washington: National Academy Press.

Kerner, O., Lindsay, J. V., Harris, F. R., Brooke, E. W., Corman, J. C., McCulloch, W. M., Abel, I.W., Thornton, C. B., Wilkins, R., Peden, K. G., Jenkins, H. (1988). The Kerner Report: The 1968 report of the national advisory commission on civil disorders. Pantheon.

Kleiman, M. A. R. (1993). Enforcement swamping: A positive-feedback mechanism in rates of illicit activity. Mathematical Computational Modeling, 17(2), 65–75.

Kling, J. R., Ludwig, J., & Katz, L. F. (2005). Neighborhood Effects on Crime for Female and Male Youth: Evidence from a Randomized Housing Voucher Experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(1), 87–130.

Kling, J. R., Liebman, J. B., & Katz, L. F. (2007). Experimental Analysis of Neighborhood Effects. Econometrica, 75(1), 83–119.

Knudsen, E. I., Heckman, J. J., Cameron, J. L., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2006). Building America’s future workforce: Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on investment in human skill development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(27), 10155–10162.

LaGrange, T., & Silverman, R. (1999). Low self-control and opportunity: Testing the general theory of crime as an explanation for gender differences in delinquency. Criminology, 37(1), 41–72.

Levitt, S. D. (2004). Understanding Why Crime Fell in the 1990s: Four Factors that Explain the Decline and Six that Do Not. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 163–190.

Ludwig, J. (2012). The Long-Term Results From the Moving to Opportunity Residential Mobility Demonstration. Cityscape, 14(2), 1–28.

Ludwig, J., & Kling, J. R. (2007). Is Crime Contagious? The Journal of Law and Economics, 50(3), 491–518.

Ludwig, J., Liebman, J. B., Kling, J. R., Duncan, G. J., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2008). What Can We Learn about Neighborhood Effects from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment? American Journal of Sociology, 114(1), 144–188.

Ludwig, J., Sanbonmatsu, L., Gennetian, L., Adam, E., Duncan, G. J., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., Kling, J. R., Lindau, S. T., Whitaker, R. C., & McDade, T. W. (2011). Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes-a randomized social experiment. The New England Journal of Medicine, 365(16), 1509–1519.

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G. J., Gennetian, L. A., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., Kling, J. R., & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2012). Neighborhood Effects on the Long-Term Well-Being of Low-Income Adults. Science, 337(6101), 1505–1510.

Ludwig, J., Duncan, G. J., Gennetian, L. A., Katz, L. F., Kessler, R. C., Kling, J. R., & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2013). Long-Term Neighborhood Effects on Low-Income Families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 103(3), 226–231.

Luttmer, E. F. P. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 963–1102.

Manski, C. F. (2000). Economic analysis of social interactions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 115–136.

Moffitt, R. A. (2001). Policy interventions, low-level equilibria, and social interactions. In S. N. Durlauf & H. P. Young (Eds.), Social dynamics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Morenoff, J. D., Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2001). Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology, 39(3), 517–558.

Olsen, E. O. (2003). Housing Programs for Low-Income Households. In R. A. Moffitt (Ed.), Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States (Vol. 3, pp. 365–442). University of Chicago Press.

Orr, L., Feins, J. D., Jacob, R., Beecroft, E., Sanbonmatsu, L., Katz, L. F., Liebman, J. B., & Kling, J. R. (2003). Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Interim Impacts Evaluation. Washington: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.

Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417–458.

Rubinowitz, L. S., & Rosenbaum, J. E. (2000). Crossing the class and color lines: From public housing to white suburbia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 603–651.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 443–478.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Raudenbush, S. (2005). Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 224–232.

Sanbonmatsu, L., Ludwig, J., Katz, L. F., Gennetian, L. A., Duncan, G. J., Kessler, R. C., Adam, E., McDade, T. W., & Lindau, S. T. (2011). Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program: Final Impacts Evaluation. DC: Washington.

Sherman, L. W. (2002). Fair and Effective Policing. In J. Q. Wilson & J. Petersilia (Eds.), Crime: Public Policies for Crime Control (pp. 383–412). Oakland: Institute for Contemporary Studies Press.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington: National Academy Press.

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., et al. (2012). The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246.

Shroder, M. (2002). Locational constraint, housing counseling, and successful lease-up in a randomized housing voucher experiment. Journal of Urban Economics, 51(2), 315–338.

Simons, L. G., Simons, R. L., Conger, R. D., & Brody, G. H. (2004). Collective Socialization and Child Conduct Problems: A Multilevel Analysis with an African American Sample. Youth & Society, 35(3), 267–292.

Warner, B. D., & Rountree, P. W. (1997). Local social ties in a community and crime model: Questioning the systemic nature of informal social control. Social Problems, 44, 520.

Wikstrom, P.-O. H., & Loeber, R. (2000). Do Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Cause Well-Adjusted Children To Become Adolescent Delinquents? a Study of Male Juvenile Serious Offending, Individual Risk and Protective Factors, and Neighborhood Context. Criminology, 38(4), 1109–1142.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago: University Press.

Zimmerman, G. M., & Messner, S. F. (2010). Neighborhood Context and the Gender Gap in Adolescent Violent Crime. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 958–980.

Zimring, F. (2011). The City That Became Safe: The City that Became Safe: New York's Lessons for Urban Crime and Its Control. New York: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by a contract from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD; C-CHI-00808) and grants from the National Science Foundation (SES-0527615), National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD040404, R01-HD040444), Centers for Disease Control (R49-CE000906), National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH077026), National Institute for Aging (P30-AG012810, R01-AG031259, and P01-AG005842-22S1), the National Opinion Research Center’s Population Research Center (through R24-HD051152-04 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development), University of Chicago’s Center for Health Administration Studies, U.S. Department of Education/Institute of Education Sciences (R305U070006), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Russell Sage Foundation, Smith Richardson Foundation, Spencer Foundation, Annie E. Casey Foundation, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Outstanding assistance with the data preparation and analysis was provided by Joe Amick, Ryan Gillette, Ray Yun Gou, Ijun Lai, Jordan Marvakov, Nicholas Potter, Fanghua Yang, Sabrina Yusuf, and Michael Zabek. The survey data collection effort was led by Nancy Gebler of the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center under subcontract to our research team. MTO data were provided by HUD. The contents of this report are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. Government, or any state or local agency that provided data. The use of Florida Department of Juvenile Justice records in the preparation of this material is acknowledged, but it is not to be construed as implying official approval of either department of the conclusions presented. New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) provided de-identified arrest data for the study. DCJS is not responsible for the methods of statistical analysis or any conclusions derived therefrom.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sciandra, M., Sanbonmatsu, L., Duncan, G.J. et al. Long-term effects of the Moving to Opportunity residential mobility experiment on crime and delinquency. J Exp Criminol 9, 451–489 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9189-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9189-9