Abstract

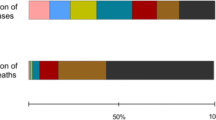

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has almost 56 million confirmed cases resulting in over 1.3 million deaths as of November 2020. This infection has proved more deadly to older adults (those >65 years of age) and those with immunocompromising conditions. The worldwide population aged 65 years and older is increasing, and the total number of aged individuals will outnumber those younger than 65 years by the year 2050. Aging is associated with a decline in immune function and chronic activation of inflammation that contributes to enhanced viral susceptibility and reduced responses to vaccination. Here we briefly review the pathogenicity of the virus, epidemiology and clinical response, and the underlying mechanisms of human aging in improving vaccination. We review current methods to improve vaccination in the older adults using novel vaccine platforms and adjuvant systems. We conclude by summarizing the existing clinical trials for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and discussing how to address the unique challenges for vaccine development presented with an aging immune system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United Nations estimates that by 2050, the size of the global over-60 population will exceed the number of younger individuals [1]. Global reductions in birth rate, coupled with reduced mortality, have increased life expectancy in developed and developing nations [2]. Aging is associated with the remodeling of the immune system, also known as immunosenescence, leading to more severe consequences of bacterial and viral infections as well as decreased protection following vaccination [3]. Immunosenescence is sustained by this multifaceted immune remodeling of the innate and adaptive branches of the human immune system that is yet to be adequately studied. Unfortunately, current vaccine strategies and platforms do not sufficiently protect older individuals [4]. The development of efficient approaches could substantially improve morbidity and mortality rates for these unprotected people. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) declared a pandemic for the coronavirus, Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) also known as coronavirus disease or COVID-19. Indeed, the case fatality ratio for those over 75 years old is 14.2%, while for those that are younger even by just 10 years, that number is significantly less at 4.87% [5]. The high fatality ratio of COVID-19 for those over 75 years old highlights the need for improved vaccine responses as part of a multifaceted approach to healthy aging. To do this, we must investigate the implications of aging on the innate and adaptive immune system function and explore the fundamental mechanisms that drive the aging process. We will summarize findings on age-related immune dysfunction to viral infections from human studies and its impact on the immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, we summarize and highlight novel directions for vaccination strategies that will expand older adult’s protection against viral infections.

Immunological basis of susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in older adults

Immunosenescence, inflammaging, and SARS-CoV-2

Alterations resulting from aging in the innate and signaling pathways have a crucial role in what is called “inflammaging” or the chronic basal production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IFNs. Inflammaging can predict frailty and mortality in those aged 65 years and older when compared with counterparts without chronic inflammation [6]. Inflammaging can arise from different sources including accumulation of self and altered molecules from damaged or dead cells which are then recognized by receptors of the innate immune system. This process, undergone by immune and non-lymphoid cell populations, fuels the progression of chronic inflammation and aging [6]. Senescent non-lymphoid cells secrete inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and growth factors which are collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype or SASP. SASP alone can cause organ dysfunction in aged individuals [7]. Recent studies have shown that this chronic activation and excessive inflammation can inhibit immunity. In illustrating this point, one study reports that the inhibition of the mTOR pathway, and therefore the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, can improve influenza vaccine response with decreased rates of infection in older adults subjects [8]. Other studies have reported reduced baseline inflammation in older adults with increased response to the shingles vaccine after p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase inhibition. This increased response might be due in part not only by the reduction of the influx of inflammatory monocytes but also by improving the memory T cell response in the skin [9]. Put together, these studies suggest tools for combatting immunosenescence and have implications for immunity of older individuals who are infected with other viral infections including SARS-CoV-2 which are particularly fatal for them. Due to an increased inflammatory environment resulting from the high level of background cytokine activation, an attenuated vaccine response is observed, leading to obvious challenges in vaccine development with regard to older adults. The following sections will discuss the effect of age on the function and phenotype of innate immune cells in human studies whose activity can be targeted to improve vaccination strategies/responses.

Remodeling of the innate immune system with aging

The phagocytic ability of macrophages from aged individuals was shown to decline with decreased levels of macrophage-secreted chemokines MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-2, and eotaxin and reduced phosphatidylinositol-2-kinase protein kinase B (PI3K-AKT) and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) signaling [10,11,12]. West Nile Virus (WNV), another ssRNA virus like SARS-CoV-2, has increased pathogenicity for older adults. Kong et al. found that infection with WNV downregulates TLR3 in monocyte-derived macrophages from older donors. This mechanism, involving impaired signaling between DC-SIGN and STAT-1, results in increased and sustained cytokine levels which may account for the increased severity of WNV in older adults [13, 14]. Interestingly, a study did show that the deficits in macrophage function might not be intrinsic owing to the observation that when macrophages were removed from the “inflammaging” environment, their response was restored [15].

Overall, studies have not found a difference with age in the total number of monocytes during a baseline state but have found an increase in the number of CD14dimCD16+ monocytes with an attenuated activation to PRR ligation [16,17,18]. Several age-related decreases specifically in response to different TLR ligation have been observed in monocytes from older individuals including TLR 7/8 [19], RIG-I and TLR 3 [20], and TLR 9 [21] pathways. Monocytes from aging human donors have been shown to have reduced RLR signaling and impaired type I IFN response to IAV infection, although this group reports preserved inflammatory cytokine production and inflammasome responses [22]. Although there is conflicting data on whether TLRs are increased, decreased, or remained the same between young and old, any change in these pathways leads to altered signaling, leading to dysregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production. It is more important to consider monocytes as different subsets in studies because of their widely varied phenotypes and functions. In a recent study investigating transcriptional and functional differences of monocyte subsets between young and old individuals, the group found that at baseline, without stimulation, surface expression of TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7 was comparable between young and older age groups. However, after stimulation with agonist to these TLRs, transcription and production of key pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFNγ, IFNα, IL-1β) and important recruitment chemokines (CCL20 and CCL8) were decreased in all subsets [23].

The initiation and control of the immune response depends heavily on the function of dendritic cells (DCs). Their role in bridging innate and adaptive immunity in aging, however, is poorly understood in humans. In response to TLR 3, TLR 7/8, and TLR 9 ligand stimulation, primary mDCs (cDC1) and pDCs had lower levels of IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α and surface expression of the TLRs but higher basal levels when compared with young donors [24]. Other studies have shown that in response to IAV infection and West Nile infection (WNV), pDCs from older adults are decreased in frequency and have decreased type I IFN production, whereas other DC populations are preserved [25]. One group found that monocyte-derived DCs (MDDCs) showed an excessive increase in pro-inflammatory TNF-α and IL-6 production after TLR4 or TLR8 stimulation or self-DNA exposure, indicating the cGAS-STING pathway [26] signifying a dysregulated pathway. However, a decrease in TLR signaling is not the only case in aging. One study found a decrease in CD80/CD86 expression and type I IFN production in MDDCs after WNV infection. This alteration occurs with impaired induction of STAT1 and IRF7 expression with similar findings in primary pDCs [27, 28]. It has also been shown that SARS-CoV infects DCs resulting in further enhancement of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion contributing to a further damaging response [29]. Recent studies from October identified impaired DC maturation and subsequent T cell-mediated responses in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection [30, 31]. More research needs to be done to determine if poor vaccine response can be overcome with additional agonist treatment. The age-related reductions in expression and activation of TLR, RLR, and inflammasome pathways have likely contributed to defects in response to viral infections resulting in age-linked susceptibility to relevant viruses like IAV and now, SARS-CoV-2.

Remodeling of the adaptive immune system with aging

As with the other components of the immune system, T cells experience a progressive decline with age. In part, the changes in T cells with age can be linked to the involution of the thymus that leads to changes in the proportions of naive and memory T cells with the result being a skewing toward memory T cells in older adults [32,33,34]. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell compartments vary in their ability to maintain naive T cells and a diverse TCR repertoire with age. While CD8+ T cells show a significant decrease in the level of naive T cells in the blood with advanced age, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells show a significant decrease in naive T cell frequency in secondary lymphoid sites [35]. While it is unclear why there are differences in the ability to maintain naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at different lymphoid sites, it has been suggested that telomere shortening due to continued peripheral proliferation eventually leads to exhaustion of proliferative capability and the eventual depletion of the overall naive T cell pool observed in older adults [36, 37]. The decline in the overall number of naive T cells with age ultimately leads to a reduction in TCR clonal diversity, especially in CD8+ T cells [38, 39]. Further skewing of the TCR repertoire occurs as memory T cells continue to accumulate with age due to clonal expansion after each encounter with cognate antigen, leading to an overall decrease in TCR diversity and overrepresentation of certain memory T cells [40, 41].

One cause of ineffective vaccine response is that recalled memory cells in older adults cannot generate functional effector responses. One example of this can be seen in defects in Granzyme B release from CTLs isolated from CMV+ older adults [42] as well as induction of Granzyme B production following ex vivo IAV challenge [43]. This effector function decline may also be due to T cell exhaustion. CD8+T cell exhaustion has been described by Song et al. as an elevated number of TIGIT+CD8+ T cells from older adults. While these cells have retained their proliferation capacity, they have impaired TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 production [44]. Since cellular immunity is strongly associated with protection from IAV, even more so than humoral responses, impairment of this function will strongly impact infection and vaccination outcome. While CD8+ T cells appear to be impacted to a greater degree by aging, CD4+ T cells also face altered and declining function with age. Nevertheless, this shift may have negative effects on vaccination success in older adults.

With age, the ability of the immune system to mount type 1 and type 2 responses appears to be altered. While several studies have shown that the aged immune response is shifted toward a Th2-dominant response, others have shown that the immune response of older adults is skewed towards a Th1-dominant response [45, 46]. It remains unclear whether the aged immune response shifts either way. Rather, it is more likely a change in kinetics with a Th1 response peaking earlier in infection or vaccination with a shift toward Th2. Nevertheless, this shift may have negative effects on vaccination success in older adults. While the characteristics of Th1 and Th2 responses are altered with age, other subsets of helper T cells are also impacted by aging including CD4+ T-follicular helper (Tfh) and T-regulatory cells (Tregs). Both subsets are important in a functional adaptive response. Older adults have lower frequencies of circulating Tfh which correlate with significantly lower IgG levels during co-culture with B cells from young adults [47]. In addition to potential intrinsic defects in circulating Tfh cells, chronic activation in older adults may drive exhaustion of these cells and lead to a poor response to vaccination that is observed. Conversely, the frequency of Tregs is the increased with age [48], although Tregs appear to maintain their functionality during the aging process. This increase in Treg frequency and maintenance of their function in older adults may further suppress the already declining immune response generated by CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in older adults individuals [49]. This loss could play a role in the reduced efficiency of vaccination that is observed in the older adults as it may prevent a robust immune response [50].

Although T cells appear to face more extensive changes with aging, B cells also experience progressive changes during the aging process. In older adults, there is a progressive decline in the overall number of B cells. There is also a decline in the diversity of B cells with age due to clonal expansion, like what is observed with the loss of T cell diversity with age [51, 52]. However, when looking at the percentage of naive B cells in the older adults, there is a significant increase in the naive B cell percentage within CD19+ cells, likely due to a steep decline in certain memory B cell subsets. While the percentage of IgM+ memory B cells appears to be maintained during the aging process, both IgG+ and IgA+ B cells and plasmablasts (PB) experience steep declines in number and percentage with age [53]. The decline in memory B cells with age appears not only to be mainly within the periphery but also to a lesser extent within the bone marrow [54]. Although the declining function of T cells may be partly to blame for the decline in switch memory B cells with age, intrinsic defects within B cells also play a role. One such intrinsic defect is the decline in the expression of transcription factor E47 and the enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) within activated B cells isolated from older adults individuals [53]. As a transcription factor, E47 regulates many B cell functions, including production of AID, an enzyme that is essential for both isotype switching and somatic hypermutation [55]. AID levels within B cells correlate with IgG production, meaning that an age-associated decline in the levels of AID likely plays a role in the decline in switch memory B cells within the older adults [55]. It has also been proposed that decreased levels of AID in B cells serves as a marker for poor vaccine response within the older adults as the decreased ability to class switch hampers the protective humoral response to vaccination [56].

Implications for aging and SARS-CoV-2 infection

It has been observed in many coronavirus infections that an early burst of type I IFN may lead to protection [57]. Unfortunately, a delay in type I IFN production is a hallmark of “inflammaging” in the older adults and could account for their increased susceptibility to coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viral infections. Even removing “inflammaging” from the picture, a delay in type I IFN with an increase in IL-6 in SARS-CoV-2 infection causes decreased ability to control viral replication resulting in respiratory epithelia damage and cytokine storm [31]. Additionally, other coronaviruses have multiple immune evasion mechanisms that limit the induction of type I IFN early in infection. Indeed, coronaviruses replicate in a double-membrane structure derived from the endoplasmic reticulum of which there are no PRRs including the important anti-viral TLR 3 and TLR7/8. SARS-CoV can add methyl groups to its viral RNA, masking its identity, thereby evading detection by MDA-5 and RIG-I [58]. SARS-CoV and the NL63 non-epidemic strain encode papain-like proteases that antagonize STING and inhibit IRF3 translocation, preventing anti-viral response [59]. Recently, it has been shown that ACE2 is an interferon stimulating gene (ISG), suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 can exploit ACE2 upregulation to enhance infection [60]. Additionally, several proteins produced by coronaviruses can interfere with other antiviral pathways including NfKB and IFNAR signaling suppressing IFN production [61]. It would not be amiss to say, then, that SARS-CoV-2 might possess other similar evasion mechanisms, which could exacerbate the defective progression from innate to adaptive immune responses in the older adults, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. In contrast, individuals who survived were able to initiate early type I IFN production and a complete progression to adaptive immunity with strong neutralizing antibody, Th1 and Tfh response, correlating with favorable outcomes [62,63,64,65] Furthermore, skewing of the older adults immune response toward a Th2-dominant response may play an important role in the increased risk of severe disease. Because of this virus’ novelty, studies looking specifically at SARS-CoV-2 are urgently needed evaluating immune dysfunction and the viral pathogenesis in older adults, especially for the context of vaccine production and explanation for increased morbidity (Fig. 1).

Cell-specific changes of the innate and adaptive human immune system associated with aging. The effects of aging in various cell types are depicted. With aging, dysregulated innate immune responses can result in failure to efficiently respond to pathogens and vaccines. The production of PAMPs and DAMPs that arise from chronic viral infections and cell damage contributes to the elevated pro-inflammatory state, also known as “inflammaging.” During inflammaging, increased basal levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are partially a result of dysregulated PRR signaling including TLRs, RIG-I, cGAS-STING, and inflammasome pathways. This increased basal activation in cell types such as monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells restricts sensitivity to new pathogens and responses to vaccines, resulting in dysregulated innate immunity and failure to progress to productive adaptive response. Changes in overall TLR protein expression have been reported with other studies reporting on specific cell subsets that expression levels remain the same, but alterations in intracellular signaling proteins like PI3K and MAPK levels decreased. The failure to progress to adaptive immunity takes the form of the overall decline in T and B cells with a reduction in TCR diversity and expansion and a progressive shift to Th2 immunity. The levels of AID, important for class switch recombination, are reduced in B cells, possibly contributing to the poor memory B cell and antibody formation and a decreased response to vaccination. PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; and DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; PRR, pattern recognition receptor; TLR, toll-like receptor; RIG-I, retinoic acid-inducible gene I; cGAS-STING, cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase; IFN, interferon; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; TCR, T cell receptor; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; TCR, T cell receptor; Th2, T helper type 2 cell; AID, activation-induced cytidine deaminase

Improving aging response to vaccines

Impaired responses to vaccination in older adults

Most vaccinations recommended for older adults are to boost preexisting immunity from past infections and vaccinations. These booster vaccines do reduce disease burden at least somewhat, but infections like IAV are still highly prevalent in the older population. The incidence of this infection is indicative of ineffective recall immunity responses. Multiple vaccine studies find that older adults have significantly reduced IAV-specific antibody responses that fail to seroconvert which would be indicative of durable antibody titers and immune protection [4, 66, 67]. In addition, the antibodies produced in older adults after IAV vaccination have a decreased ability to neutralize virus along with restricted repertoire diversity, fewer class-switched B cells and PB, and inducible co-stimulation in influenza-specific Tfh cells [67, 68]. Another group importantly evaluated monocyte subsets in young and older individuals after IAV vaccination. In response to the IAV vaccine, the induction of IL-6 in both CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+ monocytes from older adults was diminished. However, CD14+CD16+ inflammatory monocytes were majorly induced in older adults at day 2 post-vaccination [69] pushing this response toward a typical “inflammaging” profile.

It is also possible that the selection process during affinity maturation may be altered in a tissue-specific manner as selection of Ig genes in Peyer’s patch GCs decreases with age while selection within the spleen remains mostly unaltered [70]. This implies that the effects on antibody production are dependent on the site of induction and selection within older adults. These features are indicative of an altered GC response in older adults and will likely have major implications for vaccine design. Interestingly, one study has shown that the memory B cell response to an IAV vaccine in the older adults could be improved by repeated vaccination. This vaccination strategy led to the maintenance of the frequency of peripheral IAV-specific memory B cells and PB in older adults, although IAV-specific IgG was still lower than the levels seen in younger individuals [71]. The implications of this finding for vaccine design especially against a viral pathogen might mean diminished protection against influenza challenge for the older adults.

This impairment is true of even primary response vaccines like the attenuated yellow fever (YF) vaccine. Studies demonstrate that older adults generate antibodies at a slower rate as compared with young adults resulting in higher viremia 5 days post-vaccination and decreased CD8+ T cell activation at day 10 post-vaccination [125]. However, at 28 days post-vaccination, YF-specific antibodies were similar across the age groups with controlled viremia. While this may suggest that older adults have the potential to develop responses like young adults, it was shown that the neutralizing capability of the antibodies and polyfunctional effector response of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from older adults were much lower [72]. Importantly, a polyfunctional CD4+ T cell response has previously been implicated in favorable clinical outcomes in patients [73, 74]. In part, the decreased CD8+ T cell activation and proliferation following vaccination is thought to be due to a decrease in the number of naive CD8+ T cells in older adults prior to vaccination. These studies ultimately suggest that a decline in the function of CD8+ T cells with age plays an important role in the increased susceptibility to severe viral infection and poor response to vaccination that is observed in the older adults. This increase in memory Treg frequency and function also positively correlates with decreased seroconversion in older adults following vaccination with an IAV vaccine [75]. Taken together, there have been great strides in understanding the mechanisms of immunological memory after vaccination and identification of the defects in the aging immune system that can be targeted using vaccine platforms. These insights will allow for an improved vaccine strategy design that will improve immune response in older adults.

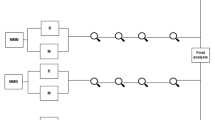

Current vaccine strategies for SARS-CoV-2

The WHO, because of the urgent and overwhelming need for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, accelerated the vaccine development process by enabling accelerated production of vaccines and diagnostics by streamlining the research and development processes [76]. Acceleration of this process has led to over 46 vaccine clinical trials currently underway. Vaccine candidates for SARS-CoV-2 include several platforms including live attenuated virus, inactivated virus, viral vector, virus-like particles, subunit, and nucleic acid vaccines (Fig. 2). Briefly, Symvivo Corporation is leading an ongoing clinical trial and evaluating the safety and immunogenicity of their bacTLR-spike vaccine (NCT04334980). This vaccine platform is unique in that a genetically modified probiotic will colonize the gut and bind to intestinal epithelial cells where it will deliver plasmids expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. This “living medicine” will sustain the expression of the S protein for the life of the probiotic enabling continued delivery and expression of the S plasmids. The Shenzhen Geno-Immune Medical Institute have developed another unique platform. While still in phase I, their platform involves a genetically modified, artificial antigen presenting cell (aAPC) expressing SARS-COV- 2-specific antigens that aims to generate large quantities of viral specific T cells quickly (NCT04299724). Novavax has developed NVX-CoV2373, a recombinant S protein vaccine made with Novavax’s proprietary nanoparticle technology and Matrix-M saponin-based adjuvant. This vaccine has entered phase III (NCT04611802) with a specific focus looking at the effect of the vaccine in at-risk adults.

Ongoing vaccine development platforms for SARS-CoV-2 (live attenuated, nucleic acid, viral vector, and protein vaccines. a Candidate vaccines in clinical trial. mRNA-1273 created by Moderna Inc./NIAID/CEPI is now in phase 3 (NCT04470427). Each participant will receive 2 IM100ug doses 28 days apart or placebo; BioNTech/Pfizer BNT162 is now in phase 3 (NCT04368728). Each participant will receive 2 IM mid dose injections 21 days apart or placebo; INO-4800 by Inovio/Wistar Institute is now in Phase 2/3 (NCT0464263). Each participant will receive 2 ID injections (1 mg/dose) 28 days apart or placebo; AZD1222 by AstraZeneca is now in phase 3 (NCT04516746). Each participant will receive 2 IM injections (5e10 vp/dose) 4 weeks apart or placebo; LV-SMENP by Shenzhen Medical Institute is now in phase 1 (NCT04276896). Each participant will receive 5e6 LV-DCs (ID) +1e8 antigen-specific CTLs (IV)/dose. Ad5-nCoV by CanSino Biologics is now in phase 3 (NCT04526990). Each participant will receive 1 IM injection or placebo; NVX-CoV2373 by Novavax is now in phase 3 (NCT04611802). Each participant will receive 2 IM injections (5 μg vaccine +50μg Matrix-M1 adjuvant/dose) 21 days apart or placebo; bacTRL-Spike by Symvivo is now in phase 1 (NCT04334980). Each participant will receive either (1) a single dose of bacTRL-Spike, equivalent to 1 billion colony forming units (cfu) of B. longum; or (2) a single dose of bacTRL-Spike, equivalent to 3 billion cfu of B. longum; or (3) a single dose of bacTRL-Spike, equivalent to 10 billion cfu of B. longum. b Preclinical vaccine candidates’ platforms (live attenuated virus, inactivated virus, replicating/non-replicating viral vector, virus like particles, subunit, and nucleic acid vaccine) *Vaccines are the frontrunners in development as of 11/30/2020. ID, intradermally; IM, intramuscular; EP, electroporation; VP, viral particles; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; CEPI, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

AstraZeneca, in partnership with the University of Oxford, has developed AZD1222, formally ChAdOx1. This vaccine contains the genetic sequence of the SARS-COV-2 S protein with a transgenic, non-replicating chimpanzee adenovirus-based vector and notably, along with Moderna and Pfizer, has become one of the three frontrunners of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The SARS-COV-2 vaccine trial has entered phase III clinical trial (NCT04516746). Another non-replicating recombinant adenovirus vector vaccine expressing full length S protein, created by CanSino Biologics, is also in development (NCT04526990) and in a phase III trial. The non-replicating feature of the adenovector vaccine makes it relatively safe in individuals with underlying diseases and children.

Interestingly, during this COVID-19 pandemic, it became noticeable that countries who still include the Bacillus Calmette-Guèrin (BCG) vaccine for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection in their vaccination regime had lower rates of infection than those that did not [77]. Because of this, clinical trials began to determine whether the BCG vaccine prophylactically protects individuals against SARS-CoV-2 infection through a process called trained immunity. Trained immunity, or innate immune memory, was conceived after observations that immunological memory occurred independently of T and B cells. It is now thought that monocytes, macrophages, DCs, and NK cells display changes in their functional programs after infection or vaccination, and these changes, probably epigenetic, lead to an increased innate response [78]. BCG vaccination through trained immunity may have non-specific but beneficial effects, and these off-target effects are already being harnessed to treat stage 0 bladder cancer and prevent respiratory infections such as pneumonia and IAV in children and older adults [79,80,81]. Since SARS-CoV-2 may harness immune evasion mechanisms similar to MERS including dampening of DC activation [30] and type I and II IFN responses [61], the inclusion of this concept in older adult vaccination might help to bolster protection during the early phases of infection. There are two clinical trials, in phases 3 and 4, underway to determine the effect of BCG vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 infection (NCT04348370, NCT04327206).

Nucleic acid vaccine strategies: tailor-made for the older adult

Nucleic acid vaccines are an alternative platform that may be able to overcome the disadvantages of vaccines in the older adults and provide the benefit of rapidly responding to emerging infections and the ability to add immune targeting molecular adjuvants to their advantage [82]. Nucleic acid vaccines can use plasmids (DNA) or antigen-encoding mRNA, complexes with a carrier that will be delivered into the cytoplasm of host cells. This technique can help prime and cross-prime APCs. This regimen has already resulted in improved immunogenicity for Clostridium difficile and specific avian IAV subtypes [83, 84]. Apart from the intrinsic immunogenicity of plasmid DNA, the ability to co-deliver a genetically encoded adjuvant perhaps raises the DNA vaccine strategy above other platforms. In this way, plasmids encoding transcription factors or other molecules can elevate the activation state of a transfected APC (see Molecular adjuvant section). While there are no licensed DNA vaccines as of yet, there are several vaccines in phase I clinical trials including a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine from Inovio and the Wistar Institute in healthy adults and the non-frail older adults. Inovio’s DNA vaccine contains plasmids that encode the SARS-CoV-2 S protein (NCT04336410). Published data show that in guinea pig and mouse studies, the vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies that can block the S protein binding to the ACE2 receptor and will re-distribute to the lungs where protection is needed [85]. So far, these studies were done using younger animals, and the phase I clinical trial is focusing on adults aged 18–50 years of age. The vaccine also does not encode for any molecular adjuvants that could help to initiate a more protective immune response from those who are aged 65 years and older.

Over the past decade, mRNA vaccine development has become a promising therapeutic tool. mRNA vaccines have several benefits over different platforms like subunit, live attenuated, killed, and even DNA vaccines. mRNA is a non-infectious platform with no risk of integration. The half-life of mRNA is shorter since it is normally degraded by host nucleases and therefore regulated through specific modifications and delivery methods. This is a benefit over DNA vaccines which may carry the risk of anti-self-nuclear or anti-self-DNA antibodies [86]. mRNA vaccines can be more efficiently delivered in vivo with the use of carrier molecules (i.e., nanoparticles), allowing for increased uptake in the cytoplasm. To increase delivery efficacy and to prevent degradation, different delivery methods have been developed including various nanoparticle formulae. Several different mRNA vaccines have been in clinical trials including those for HIV (NCT00672191), Zika (NCT03014089), and IAV (NCT03076385) as well as SARS-CoV-2 (NCT04283461). Not only may this be a strategy for increasing immune response in older adults, DNA vaccines are stable at room temperature and both DNA and RNA vaccines are economical, making them easier to develop during epidemics or pandemics.

Although DNA and mRNA vaccines have clear benefits that may aid in overcoming the poor vaccine response in the older adults, nucleic acid-based vaccines also face their own set of shortcomings. Both DNA and mRNA vaccines suffer from the difficulty in delivering exogenous nucleic acids into mammalian host cells. While the use of delivery devices like the gene gun and electroporation are currently widely used to increase in vivo transfection efficiency, these delivery devices can prevent the ability to deliver DNA or mRNA vaccines to specific tissues, like mucosal tissues. Targeting nucleic acid vaccines to certain cells types, like APCs, is also important in optimizing the efficacy of these vaccines. This particular point is important as mRNA vaccines by themselves are poor stimulators of cell-mediated immunity which is paramount for protection against infection against viruses including IAV and SARS-CoV-2 [87, 88].

Continued advances in the development of nanoparticles for the delivery of both DNA and mRNA vaccines have led to increased interest in their use to help overcome the inherent shortcomings of nucleic acid vaccines. Harnessing their ability to encapsulate and protect nucleic acids from nucleases opens the possibility to administer vaccines to tissues that were previously difficult to reach such as the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) [89]. An additional benefit of using nanoparticles for vaccine delivery is that high modularity of nanoparticles allow for the addition of molecules, like mannose, that target DCs for increased uptake and presentation of antigen [90], penetration of mucosal barriers [91], or enhanced blood retention time [92]. However, despite the benefits of nanoparticle-based vaccine delivery, a major setback for this delivery method is the poor transfection rate in vivo. Despite this limitation, nanoparticles offer a unique delivery platform for vaccines that could be adapted for the targeted development of vaccines for the older adults. Important vaccines in clinical development using this delivery system include the recombinant trivalent nanoparticle IAV vaccine (NanoFlu) in phase III clinical trial (NCT04120194) and, notably, Moderna’s mRNA-1273 vaccine (NCT04283461) and Pfizer/BioNTech (NCT04368728). Both Moderna and Pfizer’s vaccine utilize a lipid nanoparticle delivery platform, but while Moderna’s mRNA-1273 encodes a prefusion stabilized form of SARS-CoV-2 S protein, Pfizer’s BNT162b1 encodes just the receptor binding domain (RBD).

Challenges and barriers to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine strategies for older adults

Current SARS-CoV-2 vaccines face many challenges when optimizing strategy for older adults. Vaccine platforms that rely upon a normal progressive immune response without consideration for immunosenescence will potentially see a nonprotective vaccine for older adults. In general, there are two concepts that pose as a barrier to a productive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in all humans but more specifically older adults. First, it has recently been shown that 35% of healthy adults who have not been exposed to SARS-CoV2 exhibit coronavirus-specific CD4+ T cells indicating cross-reactivity in these cells between SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses [30]. Preexisting immunity can also pose a problem for adenovirus-based vectors and remains a potential caveat for that particular platform. Preexisting immunity from natural infections, including coronaviruses and adenoviruses, both responsible for the common cold, can result in sustained neutralizing viral titers. Neutralizing antibodies can reduce the uptake of the adenoviral vectors by APCs which can impact the efficacy of the vaccine [93]. The use of viral backbones like chimpanzee adenovirus vector (ChAd) could circumvent this issue as humans have little to no preexisting immunity [94] and by increasing the dose of the vector. A second barrier to a safe and efficacious SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is the occurrence of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of disease. ADE is classically associated with dengue virus where sub-neutralization titers to one virus serotype can enhance subsequent infection with another serotype via Fcγ receptors in cells like macrophages or lead to enhanced inflammation and immunopathology by excessive antibody Fc-mediated effector functions. Whether ADE can occur in SARS-CoV-2 infection remains unclear as the evidence currently remains circumstantial [95] but warrants further investigation to determine if antibodies can increase disease severity. Lastly, nucleic acid vaccines rely upon APCs to process and present vaccine antigen for effective uptake. However, APCs including monocytes, DCs, and macrophages have impaired immune functional signaling that may negatively interfere with this vaccine platform. The ability to target vaccines to APCs or conjugate antigen and adjuvant together could be used to overcome these barriers and increase the efficacy of vaccines within the older adult population.

Adjuvants: who needs them?

Traditionally, adjuvants have been used to amplify the adaptive immune response to a vaccine. The new concept of adjuvant development has been increasingly focused on not only amplifying the response but also guiding the type of adaptive response that will produce the most effective immunity specifically for each pathogen. The reason to integrate an adjuvant is twofold. First, adjuvants increase the response to the vaccine in a general population by increasing the number of individuals that will be protected after immunization and facilitate the inclusion of smaller doses of antigen, allowing for overall fewer doses of vaccine. Adjuvants are also used to increase rates of protection in populations with reduced reaction due to age, both young and old, or immunocompromising disorders, as in the use of MF89 adjuvant that is included in the IAV vaccine to enhance the response of older individuals [96]. Secondly, adjuvants can qualitatively guide a tailored immune response to specific pathogens. For example, adjuvants have been used in preclinical and clinical studies to (1) skew the type of immune response (CD4+ vs. CD8+, Th1 vs. Th2); (2) increase speed of initial response [97]; (3) alter breadth or specificity of the response [97]; (4) and increase generation of memory responses [98].

Molecular adjuvants

DNA or mRNA vaccines may offer an enhanced delivery platform that will be beneficial for older adult individuals. Molecular adjuvants, those included as plasmids in DNA or mRNA vaccines, can encode transcription factors or other molecules like cytokines and chemokines to increase stimulation and activation of APCs, even enabling them to traffic to the mucosa more effectively [99]. The upregulation of the transcription factors, NFκB and IRF, are classical danger signals that stimulate APCs. Shedlock and colleagues have shown the co-delivery of DNA encoding HIV proteins Gag and Env and NFκB via EP increased cellular and humoral responses [100]. The co-delivery of DNA encoding an IAV antigen with IRF3 (a transcription factor in many antiviral pathways) increased the percentage of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [101]. Other groups have experimented with the co-delivery of other IRFs. One group showed that the co-delivery of HIV tat antigen with IRF1 enhanced the cytotoxic and Th1 response [102]. Luo et al. utilized adaptor proteins in the RIG-I and TLR pathways to induce IAV and malaria-specific CD8+ T cell responses, respectively [103, 104]. Other approaches have used plasmids encoded with APC co-stimulatory receptors such as CD80/CD86 or cytokines and chemokines like IL-12 that promotes Th1 differentiation, APC stimulation, and trafficking to mucosal sites for efficient antiviral responses [99, 105, 106]. Recently, adenosine deaminase-1 (ADA-1), an enzyme that is normally responsible for deaminating adenosine to produce inosine, has been shown to play a role in immune function by possibly creating an immunological synapse between CD26, an ADA-1 receptor on CD4+ T cells, and other ADA-1 receptors expressed on APCs. ADA-1 has also been reported to enhance the ability of pre-Tfh to provide B cell help as a plasmid in a HIV-1 DNA vaccine [98]. The use of molecular adjuvants in DNA or mRNA vaccines remains an important strategy to combat poor immunogenicity especially in the older adults.

PRR-dependent adjuvants

Specific PRR stimulators, including TLR and RLR ligands, have been used as a strategy to boost immune responsiveness to vaccination. PRR engagement has a great potential to enhance immune protection in older individuals. These adjuvants fall into two categories: those that target antigen presentation cells (APCs) to enhance their ability to stimulate the immune environment or those that target the adaptive immune system like B and T cells. The targeted use of PRR adjuvants, alone or in combination, will likely be essential in vaccine development moving forward as each PRR adjuvant has distinct effects for overcoming the deficits in the innate and adaptive immune pathways of older individuals such as helping to stimulate APCs by overcoming lower activation of antiviral and antigen-presentation pathways.

Synthetic dsRNA agonists have been used as adjuvants and can signal through two different PRRs. Viral or synthetic dsRNA can activate TLR3 in endosomes or through the RIG-I pathway in the cytoplasm. TLR3 and RIG-I agonism has been shown to activate DCs to produce IL-12 and type I IFN, important antiviral cytokines, with improved MHC class II expression and cross-presentation [107]. There are several synthetic dsRNA TLR3 adjuvants (Poly:IC, Poly ICLC, and Poly IC12U) that have been used previously as adjuvants with DC-targeting constructs, inactivated viral vaccine, soluble proteins, and importantly, viral-like particles in aged mice [108, 109]. Poly:IC can activate both TLR3 and RIG-I pathways which can amplify the immune response by inducing activation of DCs directly and the production of type I IFNs through RIG-I [110]. RIG-I-specific adjuvants are not as advanced and are still being tested in animal models [111]. There are several candidates that have been shown to protect against H5N1 IAV and Chikungunya with intravenous and intraperitoneal injections with JetPEI transfection reagent [112, 113]. An optimized Poly:IC or RIG-I adjuvant will likely induce broad immune effects for an enhanced adaptive immunity.

LPS is a potent adjuvant but cannot be used directly in a vaccine because of the associated pyrogenic role. There are several known TLR4 adjuvants already on the market including monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and MPL formulated with alum (AS04). MPL, best known for being a component in the HBV (Fendrix) and HPV (Cervarix) vaccines, has been proven to be safe and effective [114]. MPL is recognized by TLR4 but, unlike LPS, signals only through the TIR domain-containing adaptor protein-inducing interferon β (TRIF) adaptor protein, thereby avoiding the production of high levels of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α [115]. AS04 stimulates TLR4 that contributes to the activation and maturation of APCs while repressing tolerance though Treg activity. AS04 promotes IFNɤ production by antigen specific CD4+ T cells skewing the immune response to a Th1 profile. This is beneficial for protection against intracellular pathogens. A recent human in vitro study has found a novel TLR4 agonist called GLA-SE that enhances mDC pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12) and, when combined with a split-virus vaccine and then challenged with IAV, showed a protective Th1 response [116].

TLR7/8 is an endosomal PRR that recognizes ssRNA from viruses and mediates the downstream effects through the signaling adaptor protein MyD88. Since ssRNA is rapidly degraded by host cell Rnases, several synthesized compounds were developed as type I IFN inducers. Compounds such as imidazoquinolines (Imiquimod (TLR7) and resiquimod (TLR7/8)) and guanosine/adenosine analogs can activate TLR7, TLR8, or both [117]. The dual-agonists, those activating both TLR7 and TLR8, may be the more effective agonists as multiple subsets of monocytes and DCs as well as neutrophils will be activated to induce antigen-presentation, antibody production, and Th1 skewed T cell profile for viral and parasitic vaccines [118, 119]. Gao et al. have developed an inert conjugate, unable to activate the TLR7 pathway, that was shown to increase the immunogenicity of weakly immunogenic antigens both in vitro and in vivo [120]. TLR 7 has also been used directly fused to proteins and conjugated to silica nanoshells for an increased immunogenic response [121].

TLR9 is an endosomal PRR that recognizes unmethylated cytosine phosphate guanine (CpG) motifs found in bacterial but not human DNA. TLR9 is expressed in natural killer (NK) cells, B cells, and pDCs but not in cDC1, cDC2, and monocytes [122,123,124]. TLR9 adjuvants, or synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) with CpG motifs (CpG-ODN), are perhaps the most well studied of the TLR agonists because of their complexity. All CpG motifs are recognized by TLR9 but have different quantitative effects on the immune system [125]. CpG-ODN have been shown to enhance antibody response and polarize T cells responses to a Th1 phenotype [126] including in aging models [127]. TLR9 agonists are being evaluated in the later stages of clinical development for infectious disease. For example, the current licensed hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine, Hepilsav-B, is very effective; however, about 5–10% of individuals do not respond to vaccination even after multiple doses. With the addition of CpG TLR9 adjuvant, the percentage of subjects with seroprotective immune response increased, and the frequency of non-responders decreased [128]. TLR9 adjuvants have also been studied as formulations of nanoparticles [129], virus-like particles [130], and adjuvants in a respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [131] and IAV [132]. Although TLR9 can exhibit species-specific differences, the use of this TLR as an adjuvant should still be explored [122].

The most recent innovations regarding adjuvants have come in the form of cGAS-STING agonists. The cGAS-STING response is unique among the PRR pathways. STING is an ER-resident transmembrane protein that can act in two ways. The first is through IRF3/NFκB signaling and the second is as a true sensor of cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs) like those that are synthesized by bacteria containing guanosine or adenosine monophosphates (GMP, AMP). In response to dsDNA (of viral, self, or mitochondrial origin), the host via cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) will synthesize a CDN for a potent response. This pathway is crucial for the innate immune system and mediates IFN production to viral and bacterial infections [133, 134]. The initiation of the cGAS-STING pathway mediates the activation of APCs and, therefore, antigen-specific adaptive immunity [135]. Indeed, IgM production requires cGAS-STING-dependent IFN production [136]. For this reason, STING agonists with vaccine antigen have shown to robustly increase immune protection through humoral and cell-mediated responses against bacterial, parasitic, and viral pathogens [137,138,139,140] as well as increase antigen uptake by APCs [141]. However, aging and the STING pathway, including how STING agonists can alter the aged immune system, are far less understood compared with other PRR agonists.

PRR-independent adjuvants

Due to the long history of use, aluminum-based adjuvants have a strong record of safety and successful use in licensed vaccines. More recent work looking at the efficiency of an alum-adjuvanted H5N1 inactivated vaccine in the older adults has even shown that aluminum-based adjuvants can serve as effective adjuvants in the older adults [142]. Because of its track record, several groups are studying the efficacy of alum-adjuvanted COVID-19 vaccines. In preclinical work on the vaccines, which both use the RBD of the S protein, the ability of the vaccines to generate high titers of neutralizing antibodies in both mice and rhesus macaques has been shown [143, 144]. However, while aluminum-based adjuvants can serve as safe and effective adjuvants, previous studies have shown that aluminum-based adjuvants are not always the most effective adjuvants for a given vaccine, further supporting the need for advancing research on a variety of different adjuvants in the ongoing development of a COVID-19 vaccine [145].

As the number of potential adjuvants beyond aluminum-based adjuvants grew, various oil-in-water emulsions were studied for their adjuvant properties. One such adjuvant,MF59, is a well-established, safe adjuvant that is currently used in an IAV vaccine specifically designed for older adults individuals (Fluad®, Novartis) [146]. A number of preclinical trials have shown that MF59 is a potent adjuvant in a range of vaccines, such as recombinant proteins, viral membrane antigens, peptides, and virus-like particles [147]. Several studies have also shown that MF59 is more potent than alum in various vaccines in both mice and nonhuman primates [148]. MF59’s mechanism of action is thought to work by increasing antigen uptake by APCs, inducing APC migration, and enhancing local innate immune cell activation at the injection site. Importantly, several studies have determined that MF59 use in trivalent IAV vaccines is effective in preventing IAV-related negative outcomes and hospitalizations with significantly higher antibody titers in the older adults [146, 149]. Currently, Seqirus has pledged to provide MF59 for use in the development of novel COVID-19 vaccines being developed by others.

Another adjuvant being used in the development of COVID-19 vaccines is the adjuvant system (AS) developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). AS adjuvants are combinations of immunostimulatory molecules that are designed to create stronger and broader protection when compared with single adjuvant alone [150]. Presently, GSK has committed to using AS03 in its partnered development of a COVID-19 vaccine [151]. AS03 is a combination of a squalene-in-water emulsion and vitamin E. Although the mechanism of action remains unclear, previous work has shown that AS03 is capable of inducing strong antibody responses, and the use of AS03 is thought to be best suited for vaccines where antibody-mediated protection is important [150]. Preclinical studies in ferrets have shown that an AS03-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine induced high antibody titers with good longevity and cross-reactivity while also allowing for antigen sparing [152,153,154]. Clinical trials in healthy adults and older adults also showed that the H5N1/AS03 vaccine provided a strong antibody response while requiring a relatively low antigen dose [155]. Additionally, during the 2009/2010 swine flu pandemic, AS03 was used to rapidly develop an H1N1 vaccine [150]. Therefore, the prior experience in rapidly developing vaccines using AS03 during a pandemic along with its previous results in the older adults make AS03 a promising adjuvant prospect for a COVID-19 vaccine that is effective in the older adults.

Another group of adjuvants that have shown promise in older adults in other vaccines are the saponin-based adjuvants. Saponins are plant-derived compounds that have been studied for their use as adjuvants due to their ability to enhance the innate immune response along with humoral and cellular immunity [156]. While saponins have been studied for their independent adjuvant properties, saponins have also been used to develop adjuvant systems, like immune stimulating complexes (ISCOMs). ISCOM adjuvant systems that are formed by the mixing of cholesterol, phospholipids, and saponins with a desired antigen [157]. One example of an ISCOM is Matrix-M™, a saponin-based adjuvant used in Novavax’s NanoFlu nanoparticle vaccine. As previously mentioned, NanoFlu is currently in a phase III clinical trial testing its efficacy in older adults. NanoFlu has also been granted the fast track designation by the FDA (NCT04120194). Toward the development of a COVID-19 vaccine, Novavax currently has a vaccine using the same nanoparticle-based platform and Matrix-M™ along with the S protein in phase I/II clinical trial [158]. Additionally, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) has also awarded supplemental contract funding to Adjuvance to develop its QS-21-analogue adjuvant TQL1055, a saponin-based adjuvant, for use in a COVID-19 vaccine using the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) SARS-COV-2 antigen [159]. While the current vaccine studies using saponin-based adjuvants in COVID-19 vaccine development have not explicitly focused on protection in the older adults, previous saponin-based adjuvants, like GSK’s AS01 adjuvant, have shown promise for eliciting protective immune responses in the older adults. In fact, the now-licensed varicella-zoster-virus vaccine that uses AS01 shows 97% protection in those aged 50–70 years and over 90% in those aged 80+, suggesting that saponin-based adjuvants can induce strong immunity in the older adults [160].

The more the merrier

The activation of more than one receptor could be more effective than the activation of a single pathway. Studies performed in vitro and in vivo have shown that the activation of more than one receptor enhances DC and NK response, induces a Th1 response, and stimulates cross-protective humoral protection with an IAV vaccine [161, 162]. Effective adjuvants that are currently licensed by GSK take this approach like AS01B and AS04 (MPL and alum). AS01B, a liposome-based vaccine adjuvant system, contains two immunostimulants: MPL and the saponin QS-21. AS01B is efficient in promoting cellular immune response [163] by activating APCs and inducing migration and activation of other innate cells like monocytes [3]. AS01B is included in the Shringrix vaccine for persons aged 50 years or older. One study presents a novel viral vaccine adjuvant that contains two synthetic ligands for TLR4 and TLR7. Separately, the adjuvants induce different responses (Th1 vs. Th2) but together, along with a recombinant antigen from IAV, a robust and rapid humoral immunity that protected against lethal challenge was observed [161]. As combination adjuvant systems can be a powerful tool in vaccine development, future studies should focus on determining the variation on adjuvant efficacy due to age. It has been reported that combination adjuvants can vary with age (newborn vs. older adults), so phase III efficacy trials should make sure to include both at-risk age groups [164].

Conclusions and outlook

Despite the urgency in developing vaccines against members of the coronavirus family, there are relatively few successful vaccines that have been in development for SARS-CoV or Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)-CoV. Like SARS-CoV-2, the S protein of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV is the principal antigenic component that induces antibodies to block viral entry and stimulates immune responses from the host and so has been the target of the vaccine development efforts. Vaccine studies for SARS-CoV-1 began using the full-length S protein and were tested in animal models (mice, ferrets, non-human primates (NHP)). However, the outcomes of these vaccines included harmful immune responses resulting in liver damage and enhanced infection after viral challenge [165]. No human clinical studies were done, and the vaccine effort against SARS-CoV diminished when the virus subsided [166, 167]. Likewise, there are currently no clinically approved MERS-CoV vaccines. Multiple vaccines in the pipeline have been developed against the S protein, but several vaccines, unlike SARS-CoV-1, target specific regions within the S protein like the RBD and so have not shown the same harmful effects.

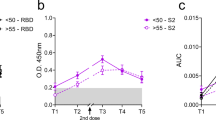

Despite this improvement, few of these vaccines in clinical trials have addressed the concerns in vaccine development for those who are older adults. SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, and the current SARS-CoV-2 all have the biggest case fatality rate in the ages 65 years and above, yet very few groups design vaccines with this in mind [168]. A limited number of trials include those over 65 years old in earlier phases to determine if protective immune responses can be elicited. For example. Novavax’s protein subunit vaccine has progressed to phase III with no published results, but, as previously mentioned above, the same company has completed a phase III clinical trial with this platform against IAV (NanoFlu, NCT04120194). In adults 65 years and older, NanoFlu was shown to be well tolerated and achieved significantly higher geometric mean titers (GMT) and seroconversion rates when compared with Fluzone Quadrivalent vaccine. It may come as no surprise that the three frontrunners include two mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer, and an adenoviral vector vaccine from AstraZeneca. Phases I and II of Moderna’s clinical trial included those aged 18–99 years of age; however, as of this review’s publication, no data have been released from the experimental arms that looked at ages 70 years and above, although they have now moved into phase III. Phase I trial has concluded that this vaccine is safe and well tolerated [169], and interim results from phase III were just released stating that the vaccine safe and effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 in adults [170]. A third nanoparticle vaccine, being developed by Pfizer and BioNTech, looks at three age groups: 18–55, 65–85, and 18–85 years. It was recently announced that Pfizer’s vaccine is also safe and well tolerated and met all primary efficacy endpoints [171] but with no published or released results regarding their older adult study trial arm. With these promising clinical trial results, it is important to reflect on certain aspects of what each study has focused on measuring for their primary outcomes. Each frontrunner vaccine has said that they have met their primary outcomes, including whether the vaccine elicits protection. However, it remains to be seen whether the vaccines can elicit sterilizing immunity or just rather protect against symptoms in the infected individual. In the end, it will be of great interest to know the results of each clinical trial at the higher end of the age spectrum considering the dire consequences of a vaccine that cannot protect those that need it most.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has galvanized many efforts to protect the population from further infection and to attenuate the disease of those currently infected. Viral entry inhibitors like Remdesivir are getting their time in the spotlight with RNA replication inhibitors following closely behind. With the recent Remdesivir clinical trial ending early due to overwhelming positive evidence, it seems we have finally been able to turn the page with an effective treatment against SARS-CoV-2 (NCT04280705). While so far we have three candidates that have emerged as frontrunners, it still must be stated that any final approach must include strategies that are tailored to the aging immune system for the most at-risk population in this pandemic. Most of the current COVID-19 vaccine strategies rely upon parenteral vaccine administration. While a mucosal site vaccine strategy would be complicated, using a mucosal targeting adjuvant with a nanoparticle vaccine platform might be extremely effective especially in the at-risk older adult population. Moving forward, a better knowledge of the specific deficits in key immunological and antiviral pathways cannot be understated. Strategies for vaccinating younger individuals cannot be simply translated to older populations and can, in fact, be harmful [172]. Studies into immunological aging provide a great opportunity to understand how these challenges may be overcome and successful vaccination tactics developed. Until more clinical and basic science studies are completed, including studies focusing on long-term immunity from vaccines and host immune response against SARS-CoV-2, vaccine development will continue in hopes of global mass immunization.

Data availability

NA

References

Nations U. World Population Prospects 2019. 2019.

UnitedNations. World population ageing: United Nations [Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf.

Del Giudice G, Goronzy JJ, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Lambert P-H, Mrkvan T, Stoddard JJ, et al. Fighting against a protean enemy: immunosenescence, vaccines, and healthy aging. npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease. 2017;4(1):1.

Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24(8):1159–69.

Yang W, Kandula S, Huynh M, Greene SK, Van Wye G, Li W, et al. Estimating the infection-fatality risk of SARS-CoV-2 in New York City during the spring 2020 Pandemic wave: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis.

Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Vitale G, Capri M, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and ‘Garb-aging’. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28(3):199–212.

Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(9):505–22.

Mannick JB, Morris M, Hockey H-UP, Roma G, Beibel M, Kulmatycki K, et al. TORC1 inhibition enhances immune function and reduces infections in the elderly. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(449):eaaq1564.

Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Chambers ES, Suárez-Fariñas M, Sandhu D, Fuentes-Duculan J, Patel N, et al. Enhancement of cutaneous immunity during aging by blocking p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase–induced inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(3):844–56.

Swift ME, Burns AL, Gray KL, DiPietro LA. Age-related alterations in the inflammatory response to dermal injury. J Investig Dermatol. 2001;117(5):1027–35.

Verschoor CP, Johnstone J, Loeb M, Bramson JL, Bowdish DME. Anti-pneumococcal deficits of monocyte-derived macrophages from the advanced-age, frail elderly and related impairments in PI3K-AKT signaling. Hum Immunol. 2014;75(12):1192–6.

Mitzel DN, Lowry V, Shirali AC, Liu Y, Stout-Delgado HW. Age-enhanced endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to increased Atg9A inhibition of STING-mediated IFN-β production during <em>Streptococcus pneumoniae</em> infection. J Immunol. 2014;192(9):4273.

Kong K-F, Wang X, Anderson JF, Fikrig E, Montgomery RR. West Nile virus attenuates activation of primary human macrophages. Viral Immunol. 2008;21(1):78–82.

Kong K-F, Delroux K, Wang X, Qian F, Arjona A, Malawista SE, et al. Dysregulation of TLR3 impairs the innate immune response to West Nile virus in the elderly. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7613–23.

Brown BN, Sicari BM, Badylak SF. Rethinking regenerative medicine: a macrophage-centered approach. Front Immunol. 2014;5:510.

Albright JM, Dunn RC, Shults JA, Boe DM, Afshar M, Kovacs EJ. Advanced age alters monocyte and macrophage responses. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;25(15):805–15.

Nyugen J, Agrawal S, Gollapudi S, Gupta S. Impaired functions of peripheral blood monocyte subpopulations in aged humans. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30(6):806–13.

Seidler S, Zimmermann HW, Bartneck M, Trautwein C, Tacke F. Age-dependent alterations of monocyte subsets and monocyte-related chemokine pathways in healthy adults. BMC Immunol. 2010;11(1):30.

van Duin D, Allore HG, Mohanty S, Ginter S, Newman FK, Belshe RB, et al. Prevaccine determination of the expression of costimulatory B7 molecules in activated monocytes predicts influenza vaccine responses in young and older adults. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(11):1590–7.

Molony RD, Nguyen JT, Kong Y, Montgomery RR, Shaw AC, Iwasaki A. Aging impairs both primary and secondary RIG-I signaling for interferon induction in human monocytes. Science Signaling. 2017;10(509).

Wang Q, Westra J, van der Geest KSM, Moser J, Bijzet J, Kuiper T, et al. Reduced levels of cytosolic DNA sensor AIM2 are associated with impaired cytokine responses in healthy elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2016;78:39–46.

Pillai PS, Molony RD, Martinod K, Dong H, Pang IK, Tal MC, et al. Mx1 reveals innate pathways to antiviral resistance and lethal influenza disease. Science. 2016;352(6284):463.

Metcalf TU, Wilkinson PA, Cameron MJ, Ghneim K, Chiang C, Wertheimer AM, et al. Human Monocyte Subsets Are Transcriptionally and Functionally Altered in Aging in Response to Pattern Recognition Receptor Agonists. The Journal of Immunology. 2017.

Panda A, Qian F, Mohanty S, van Duin D, Newman FK, Zhang L, et al. Age-associated decrease in TLR function in primary human dendritic cells predicts influenza vaccine response. J Immunol. 2010;184(5):2518.

Prakash S, Agrawal S, Cao J-n, Gupta S, Agrawal a. impaired secretion of interferons by dendritic cells from aged subjects to influenza. AGE. 2013;35(5):1785–1797.

Agrawal A, Tay J, Ton S, Agrawal S, Gupta S. Increased reactivity of dendritic cells from aged subjects to self-antigen, the human DNA. J Immunol. 2009;182(2):1138.

Qian F, Wang X, Zhang L, Lin A, Zhao H, Fikrig E, et al. Impaired interferon signaling in dendritic cells from older donors infected in vitro with West Nile virus. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(10):1415–24.

Sridharan A, Esposo M, Kaushal K, Tay J, Osann K, Agrawal S, et al. Age-associated impaired plasmacytoid dendritic cell functions lead to decreased CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity. Age (Dordr). 2011;33(3):363–76.

Tseng C-TK, Perrone LA, Zhu H, Makino S, Peters CJ. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and the innate immune responses: modulation of effector cell function without productive infection. J Immunol. 2005;174(12):7977.

Zhou R, To KK-W, Wong Y-C, Liu L, Zhou B, Li X, et al. Acute SARS-CoV-2 infection impairs dendritic cell and T cell responses. Immunity. 2020;53(4):864–77.e5.

Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu W-C, Uhl S, Hoagland D, Møller R, et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181(5):1036–45.e9.

Bektas A, Schurman SH, Sen R, Ferrucci L. Human T cell immunosenescence and inflammation in aging. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102(4):977–88.

Kyoizumi S, Kubo Y, Kajimura J, Yoshida K, Imai K, Hayashi T, et al. Age-associated changes in the differentiation potentials of human circulating hematopoietic progenitors to T- or NK-lineage cells. J Immunol. 2013;190(12):6164–72.

Palmer S, Albergante L, Blackburn CC, Newman TJ. Thymic involution and rising disease incidence with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115(8):1883–8.

Thome JJ, Grinshpun B, Kumar BV, Kubota M, Ohmura Y, Lerner H, et al. Longterm maintenance of human naive T cells through in situ homeostasis in lymphoid tissue sites. Sci Immunol. 2016;1(6).

Kilpatrick RD, Rickabaugh T, Hultin LE, Hultin P, Hausner MA, Detels R, et al. Homeostasis of the naive CD4+ T cell compartment during aging. J Immunol. 2008;180(3):1499–507.

Naylor K, Li G, Vallejo AN, Lee WW, Koetz K, Bryl E, et al. The influence of age on T cell generation and TCR diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7446–52.

Britanova OV, Putintseva EV, Shugay M, Merzlyak EM, Turchaninova MA, Staroverov DB, et al. Age-related decrease in TCR repertoire diversity measured with deep and normalized sequence profiling. J Immunol. 2014;192(6):2689–98.

Yoshida K, Cologne JB, Cordova K, Misumi M, Yamaoka M, Kyoizumi S, et al. Aging-related changes in human T-cell repertoire over 20years delineated by deep sequencing of peripheral T-cell receptors. Exp Gerontol. 2017;96:29–37.

Messaoudi I, Lemaoult J, Guevara-Patino JA, Metzner BM, Nikolich-Zugich J. Age-related CD8 T cell clonal expansions constrict CD8 T cell repertoire and have the potential to impair immune defense. J Exp Med. 2004;200(10):1347–58.

Egorov ES, Kasatskaya SA, Zubov VN, Izraelson M, Nakonechnaya TO, Staroverov DB, et al. The changing landscape of naive T cell receptor repertoire with human aging. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1618.

Zhou X, McElhaney JE. Age-related changes in memory and effector T cells responding to influenza a/H3N2 and pandemic a/H1N1 strains in humans. Vaccine. 2011;29(11):2169–77.

Haq K, Fulop T, Tedder G, Gentleman B, Garneau H, Meneilly GS, et al. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity predicts a decline in the T cell but not the antibody response to influenza in vaccinated older adults independent of type 2 diabetes status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(9):1163–70.

Song Y, Wang B, Song R, Hao Y, Wang D, Li Y, et al. T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain contributes to CD8+ T-cell Immunosenescence. Aging Cell. 2018;17(2):e12716.

Bektas A, Zhang Y, Lehmann E, Wood WH, Becker KG, Madara K, et al. Age-associated changes in basal NF-κB function in human CD4<sup>+</sup> T lymphocytes via dysregulation of PI3 kinase. Aging. 2014;6(11):957–69.

Deng Y, Jing Y, Campbell AE, Gravenstein S. Age-related impaired type 1 T cell responses to influenza: reduced activation ex vivo, decreased expansion in CTL culture in vitro, and blunted response to influenza vaccination in vivo in the elderly. J Immunol. 2004;172(6):3437–46.

Gustafson CE, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. T follicular helper cell development and functionality in immune ageing. Clin Sci (Lond). 2018;132(17):1925–35.

Hou PF, Zhu LJ, Chen XY, Qiu ZQ. Age-related changes in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and their relationship with lung cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173048.

Trzonkowski P, Szmit E, Myśliwska J, Myśliwski A. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells inhibit cytotoxic activity of CTL and NK cells in humans-impact of immunosenescence. Clin Immunol. 2006;119(3):307–16.

Wagner A, Garner-Spitzer E, Jasinska J, Kollaritsch H, Stiasny K, Kundi M, et al. Age-related differences in humoral and cellular immune responses after primary immunisation: indications for stratified vaccination schedules. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9825.

Gibson KL, Wu YC, Barnett Y, Duggan O, Vaughan R, Kondeatis E, et al. B-cell diversity decreases in old age and is correlated with poor health status. Aging Cell. 2009;8(1):18–25.

Dunn-Walters DK, Ademokun AA. B cell repertoire and ageing. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(4):514–20.

Frasca D, Landin AM, Lechner SC, Ryan JG, Schwartz R, Riley RL, et al. Aging down-regulates the transcription factor E2A, activation-induced cytidine deaminase, and Ig class switch in human B cells. J Immunol. 2008;180(8):5283–90.

Pritz T, Lair J, Ban M, Keller M, Weinberger B, Krismer M, et al. Plasma cell numbers decrease in bone marrow of old patients. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(3):738–46.

Merani S, Pawelec G, Kuchel GA, McElhaney JE. Impact of aging and Cytomegalovirus on immunological response to influenza vaccination and infection. Front Immunol. 2017;8:784.

Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Phillips M, Mendez NV, Landin AM, et al. Unique biomarkers for B-cell function predict the serum response to pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine. Int Immunol. 2012;24(3):175–82.

Channappanavar R, Fehr AR, Zheng J, Wohlford-Lenane C, Abrahante JE, Mack M, et al. IFN-I response timing relative to virus replication determines MERS coronavirus infection outcomes. J Clin Invest. 2019;130(9):3625–39.

Züst R, Cervantes-Barragan L, Habjan M, Maier R, Neuman BW, Ziebuhr J, et al. Ribose 2′-O-methylation provides a molecular signature for the distinction of self and non-self mRNA dependent on the RNA sensor Mda5. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(2):137–43.

Sun L, Xing Y, Chen X, Zheng Y, Yang Y, Nichols DB, et al. Coronavirus papain-like proteases negatively regulate antiviral innate immune response through disruption of STING-mediated signaling. PloS one. 2012;7(2):e30802-e.

Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, Mbano IM, Miao VN, Tzouanas CN, et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181(5):1016–35.e19.

Frieman M, Yount B, Heise M, Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Palese P, Baric RS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ORF6 antagonizes STAT1 function by sequestering nuclear import factors on the rough endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi membrane. J Virol. 2007;81(18):9812.

Cunha LL, Perazzio SF, Azzi J, Cravedi P, Riella LV. Remodeling of the immune response with aging: Immunosenescence and its potential impact on COVID-19 immune response. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1748.

Roncati L, Nasillo V, Lusenti B, Riva G. Signals of Th2 immune response from COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(6):1419–20.

Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, Mateus J, Dan JM, Moderbacher CR, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020.

Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Corry DB. The potential role of Th17 immune responses in coronavirus immunopathology and vaccine-induced immune enhancement. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(4–5):165–7.

van den Berg SPH, Wong A, Hendriks M, Jacobi RHJ, van Baarle D, van Beek J. Negative effect of age, but not of latent Cytomegalovirus infection on the antibody response to a novel influenza vaccine strain in healthy adults. Front Immunol. 2018;9:82.

Nuñez IA, Carlock MA, Allen JD, Owino SO, Moehling KK, Nowalk P, et al. Impact of age and pre-existing influenza immune responses in humans receiving split inactivated influenza vaccine on the induction of the breadth of antibodies to influenza a strains. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0185666.

Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Blomberg BB. Age effects on B cells and humoral immunity in humans. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(3):330–5.

Mohanty S, Joshi SR, Ueda I, Wilson J, Blevins TP, Siconolfi B, et al. Prolonged proinflammatory cytokine production in monocytes modulated by interleukin 10 after influenza vaccination in older adults. J Infect Dis. 2014;211(7):1174–84.

Banerjee M, Mehr R, Belelovsky A, Spencer J, Dunn-Walters DK. Age- and tissue-specific differences in human germinal center B cell selection revealed by analysis of IgVH gene hypermutation and lineage trees. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(7):1947–57.

Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Blomberg BB. The generation of memory B cells is maintained, but the antibody response is not, in the elderly after repeated influenza immunizations. Vaccine. 2016;34(25):2834–40.

Schulz AR, Mälzer JN, Domingo C, Jürchott K, Grützkau A, Babel N, et al. Low thymic activity and dendritic cell numbers are associated with the immune response to primary viral infection in elderly humans. J Immunol. 2015;195(10):4699–711.

Boyd A, Almeida JR, Darrah PA, Sauce D, Seder RA, Appay V, et al. Pathogen-specific T cell polyfunctionality is a correlate of T cell efficacy and immune protection. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128714.

Goncalves Pereira MH, Figueiredo MM, Queiroz CP, Magalhaes TVB, Mafra A, Diniz LMO, et al. T-cells producing multiple combinations of IFNgamma, TNF and IL10 are associated with mild forms of dengue infection. Immunology. 2020;160(1):90–102.

van der Geest KS, Abdulahad WH, Tete SM, Lorencetti PG, Horst G, Bos NA, et al. Aging disturbs the balance between effector and regulatory CD4+ T cells. Exp Gerontol. 2014;60:190–6.

Organization WH. R&D Blueprint and COVID-19. 2020 [11/28/2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/blueprint/covid-19.

Curtis N, Sparrow A, Ghebreyesus TA, Netea MG. Considering BCG vaccination to reduce the impact of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020.

Netea MG, Joosten LA, Latz E, Mills KH, Natoli G, Stunnenberg HG, et al. Trained immunity: a program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science. 2016;352(6284):aaf1098.

Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The influence of BCG on vaccine responses – a systematic review. Expert Rev Vaccin. 2018;17(6):547–54.

Hollm-Delgado M-G, Stuart EA, Black RE. Acute lower respiratory infection among Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG)–vaccinated children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):e73.

Pollard AJ, Finn A, Curtis N. Non-specific effects of vaccines: plausible and potentially important, but implications uncertain. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(11):1077.

Klinman DM, Conover J, Bloom ET, Weiss W. Immunogenicity and efficacy of a DNA vaccine in aged mice. J Gerontol Series A. 1998;53A(4):B281–B6.

Baliban SM, Michael A, Shammassian B, Mudakha S, Khan AS, Cocklin S, et al. An optimized, synthetic DNA vaccine encoding the toxin a and toxin B receptor binding domains of Clostridium difficile induces protective antibody responses in vivo. Infect Immun. 2014;82(10):4080–91.

DeZure AD, Coates EE, Hu Z, Yamshchikov GV, Zephir KL, Enama ME, et al. An avian influenza H7 DNA priming vaccine is safe and immunogenic in a randomized phase I clinical trial. NPJ vaccines [Internet]. 2017 2017; 2:[15 p.]. Available from: http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29263871, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-017-0016-6, https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC5627236, https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC5627236?pdf=render, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5627236/pdf/41541_2017_Article_16.pdf.

Smith TRF, Patel A, Ramos S, Elwood D, Zhu X, Yan J, et al. Immunogenicity of a DNA vaccine candidate for COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2601.