Abstract

Lobbying by multinational business firms drives the agenda of international trade politics. We match Fortune Global 500 firms to WTO disputes in which they have a stake and to their political activities using public disclosure data. The quantitative evidence reveals traces of a principal-agent relationship between major MNCs and the US Trade Representative (USTR). Firms lobby and make political contributions to induce the USTR to lodge a WTO dispute, and once a dispute begins, firms increase their political activity in order to keep USTR on track. Lobbying is overwhelmingly patriotic—the side opposing the US position is barely represented—and we see little evidence of MNCs lobbying against domestic protectionism. When the United States is targeted in a dispute, lobbying by defendant-side firms substantially delays settlement, as the affected firms pressure the government to reject concessions. Lobbying on the complainant side does not delay dispute resolution, as complainant-side firms have mixed incentives, to resolve disputes quickly as well as to hold out for better terms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some scholars argue that the size of the economy affects involvement in disputes (Bown 2005; Guzman and Simmons 2005; Horn and Mavroidis 2011; Sattler and Bernauer 2011), and others focus on past experience (Davis and Bermeo 2009; Conti 2010), or exchange-rate regimes (Copelovitch and Pevehouse 2011; Broz and Werfel 2014; Bown and Reynolds 2015; Betz and Kerner 2016). While some developing countries have actively initiated WTO disputes, most do not, and empirical studies show that country-level factors such as weak legal capacity, lack of resources, or fear of retaliation deter developing countries from initiating disputes (Guzman and Simmons 2005; Bown 2005; Kim 2008; Busch et al. 2009; Elsig and Stucki 2012). Other studies investigate country-level factors affecting escalation of disputes (Busch and Reinhardt 2000, 2003), and Busch and Reinhardt (2006) and Johns and Pelc (2014) study the role of third-party states during dispute resolution. Other scholarship focuses on domestic politics. Chaudoin (2014) and Pervez (2015) argue that the timing of dispute initiation is driven by elections. The working assumption of all of these studies is that states are the relevant actors.

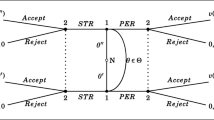

Formally, a principal-agent relationship exists whenever one actor, the principal, attempts to induce another actor to perform or comply. The agent must have an information advantage of some sort (for example, local knowledge, expertise, hidden effort, or private information about its type) to make the problem theoretically interesting.

A lobbying report provided by Airbus (see the Online Appendix Fig. A1) indicates that Airbus lobbied regarding civil aircraft issues, and in section 16 reports that specific lobbying issues are “matters pertaining to the US and European civil aviation industries.”

A selected list of law firms involved in WTO cases is in Bown (2010).

For further information about the dataset, see Davis (2012), 123–32.

Davis (2012) considers only nine WTO members that have the highest trade volumes with the United States. These nine are Canada, EU, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Brazil, India, Malaysia, and Singapore. Note that China is one of the major trade partners of the United States, but it is excluded because it joined the WTO only in 2001.

Data available at http://www.opensecrets.org.

Data available at http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/stanstructuralanalysisdatabase.htm.

In addition, we analyze the effects of political contributions to the Republicans and the Democrats separately. The results are similar to those reported above, and we report them in the Online Appendix Table B2.

A description of the text analysis method used in the data collection and the list of involved firms can be found in the Online Appendix Section A.3.

Data available at http://www.opensecrets.org.

Details on the methodology are available at http://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/methodology.php.

Jensen et al. (2015) show that firms with more vertical FDI are less likely to file antidumping petitions, and we find that FDI is also associated with lower levels of lobbying during WTO disputes.

Since we consider four categories in our analyses–US is complainant, complainant-side firms; US is complainant, defendant-side firms; US is defendant, complainant-side firms; and US is defendant, defendant-side firms–we use four different TIPs variables to capture these bilateral relations.

The results are robust to other model selections (pooling and random effects). A Hausman test indicates that fixed-effect models are appropriate.

Additional results in the Online Appendix show that a model that does not control for selection effects does exhibit a significant positive effect of a different variable, political contributions, on the probability of a pro-complainant ruling (Table B5), and this result survives in models that control for selection into WTO dispute initiation (Table B4) (We use industry-level political contributions data because the unit of analysis for the selection model is an industry-level trade barrier). However, the result of firm-level lobbying on panel rulings is insignificant when we model the selection problem as survival of a dispute until the panel rules.

It would appear natural to include lobbying data in the selection stage in models (3) and (4), we cannot do so because the data are not available. Since the consultation stage only lasts a few months and the lobbying data are collected annually, we cannot specify the amount of lobbying spent in the first stage.

We update the dataset because its coverage ends in 2010. We consider both legislative and presidential elections.

These results are consistent with the magnitudes observed in some well-known cases. In US-Softwood Lumber, the United States lumber industry spent on average $1.5 million to influence the International Trade Commission (ITC), which had investigated imports of softwood lumber from Canada and determined that Canadian imports were subsidized and sold in the United States at less than fair value. The Canadian government challenged this measure by initiating a dispute on 20 December 2002 at the WTO. The dispute took almost four years before it was resolved. In a case with higher stakes, US-Zeroing, several countries lodged a complaint against the United States for its use of “zeroing” methodology in its antidumping margin calculations. The WTO panel ruled that using zeroing is inconsistent with the Antidumping Agreement, but US industries spent on average $5.9 million per year on lobbying, and US compliance with the ruling was delayed for eight years.

Japanese steel producers related to this case are Nippon Steel, NKK Corp., Kawasaki Steel Corp., Kobe Steel Ltd., Sumitomo Metal Industries Ltd., and Nisshin Steel Co.

WTO Panel report WT/DS184/R.

New York Times article, “Clinton warns US will fight cheap imports.” Source: http://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/11/business/international-business-clinton-warns-us-will-fight-cheap-imports.html.

House hearing in the 106 Congress to discuss steel trade issues, which is available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-106hhrg57306/html/CHRG-106hhrg57306.htm.

New York times article, “New US guards promised against steel import surges.” Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2000/07/26/business/new-us-guards-promised-against-steel-import-surges.html

WTO Panel report WT/DS184/R.

According to the Article XXI, prompt compliance with recommendations or rulings of the DSB is required in order to ensure effective resolution of disputes for the benefit of all members.

A recent status report is WT/DS184/15/Add.171 [accessed 12 April 2017].

“Japan-US steel dispute to be resolved by WTO,” Japan Times, July 18, 2000. www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2000/07/18/business/japan-u-s-steel-dispute-to-be-resolved-by-wto/.

Compared to imports during a period before the US imposed antidumping measures in 1998 (6.07 million), steel imports from Japan decreased to only 1.93 million tons in 2000 (Keisuke 2006).

Japanese steel producers also spend on lobbying, but the amount is relatively small. Sumitomo Metal Industries Ltd spent a mere $40,000 in 1999 and this amount decreased to $20,000 in 2002.

References

Antràs, P., & Helpman, E. (2004). Global sourcing. Journal of Political Economy, 112(3), 552–580.

Austen-Smith, D. (1993). Information and influence: Lobbying for agendas and votes. American Journal of Political Science, 37(3), 799–833.

Bernard, A.B. et al. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. The American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290.

Betz, T., & Kerner, A. (2016). Real exchange rate overvaluation and WTO dispute initiation in developing countries. International Organization, 70(4), 797.

Bliss, H., & Russett, B. (1998). Democratic trading partners: The liberal connection, 1962–1989. The Journal of Politics, 60(4), 1126–1147.

Bombardini, M. (2008). Firm heterogeneity and lobby participation. Journal of International Economics, 75(2), 329–348.

Bormann, N.-C., & Golder, M. (2013). Democratic electoral systems around the world, 1946–2011. Electoral Studies, 32(2), 360–369.

Bown, C.P. (2004). On the economic success of GATT/WTO dispute settlement. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(3), 811–823.

Bown, C.P. (2005). Participation in WTO dispute settlement: Complainants, interested parties, and free riders. The World Bank Economic Review, 19(2), 287–310.

Bown, C.P. (2010). Self-enforcing trade: Developing countries and WTO dispute settlement. Washington: Brookings Institution.

Bown, C.P., & Reynolds, K.M. (2015). Trade flows and trade disputes. The Review of International Organizations, 10(2), 145–177.

Broz, J.L., & Werfel, S.H. (2014). Exchange rates and industry demands for trade protection. International Organization, 68(02), 393–416.

Brutger, R. (2017). Litigation for sale: Private firms and WTO dispute escalation. Working paper.

Busch, M.L., & Reinhardt, E. (1999). Industrial location and protection: The political and economic geography of U.S. nontariff barriers. American Journal of Political Science, 43(4), 1028– 1050.

Busch, M.L., & Reinhardt, E. (2000). Bargaining in the shadow of the law: Early settlement in GATT/WTO disputes. Fordham International Law Journal, 24, 158.

Busch, M.L., & Reinhardt, E. (2003). Developing countries and general agreement on tariffs and trade/world trade organization dispute settlement. Journal of World Trade, 37(4), 719–735.

Busch, M., & Reinhardt, E. (2006). Three’s a crowd: Third parties and WTO dispute settlement. World Politics, 58(03), 446–477.

Busch, M., & Reinhardt, E. (2007). Developing countries and GATT/WTO dispute settlement. In Berman, G., & Mavroidis, P. (Eds.) WTO law and developing countries (pp. 195–212). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Busch, M.L., Reinhardt, E., Shaffer, G. (2009). Does legal capacity matter? A survey of WTO members. World Trade Review, 8(04), 559–577.

Chalmers, A.W. (2013). Trading information for access: Informational lobbying strategies and interest group access to the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(1), 39–58.

Chaudoin, S. (2014). Audience features and the strategic timing of trade disputes. International Organization, 68(04), 877–911.

Conti, J.A. (2010). Learning to dispute: Repeat participation, expertise, and reputation at the world trade organization. Law & Social Inquiry, 35(3), 625–662.

Copelovitch, M.S., & Pevehouse, J.C. (2011). Currency wars by other means? Exchange rates and WTO dispute initiation. In IPES conference.

Davis, C.L. (2012). Why adjudicate?: Enforcing trade rules in the WTO. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Davis, C.L., & Bermeo, S.B. (2009). Who files? Developing country participation in GATT/WTO adjudication. The Journal of Politics, 71(03), 1033–1049.

Davis, C.L., & Shirato, Y. (2007). Firms, governments, and WTO adjudication: Japan’s selection of WTO disputes. World Politics, 59(02), 274–313.

De Bièvre, D. et al. (2016). International institutions and interest mobilization: The WTO and lobbying in EU and US trade policy. Journal of World Trade, 50(2), 289–312.

Eckhardt, J. (2011). Firm lobbying and EU trade policymaking: Reflections on the anti-dumping case against chinese and vietnamese shoes (2005–2011). J World Trade, 45, 965.

Eckhardt, J., & De Bievre, D. (2015). Boomerangs over Lac L?eman: Transnational lobbying and foreign venue shopping in WTO dispute settlement. World Trade Review, 14(3), 507–530.

Elsig, M., & Pollack, M.A. (2014). Agents, trustees, and international courts: The politics of judicial appointment at the world trade organization. European Journal of International Relations, 20(2), 391–415.

Elsig, M., & Stucki, P. (2012). Low-income developing countries and WTO litigation: Why wake up the sleeping dog? Review of International Political Economy, 19(2), 292–316.

Finger, J.M. (2010). Administered Protection in the GATT/WTO System (October 4, 2010). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1769230 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1769230.

Gawande, K., Hoekman, B., Cui, Y. (2015). Global supply chains and trade policy responses to the 2008 crisis. The World Bank Economic Review, 29(1), 102–128.

Gilligan, M.J. (1997). Empowering exporters: Reciprocity, delegation, and collective action in american trade policy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Goldstein, J.L., & Steinberg, R.H. (2008). Negotiate or litigate? Effects of WTO judicial delegation on us trade politics. Law and Contemporary Problems, 71(1), 257–282.

Grier, K.B., Munger, M.C., Roberts, B.E. (1994). The determinants of industry political activity, 1978?-1986. American Political Science Review, 88(04), 911–926.

Grossman, G.M., & Helpman, E. (2002). Interest groups and trade policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Guzman, A.T., & Simmons, B.A. (2002). To settle or empanel? An empirical analysis of litigation and settlement at the world trade organization. The Journal of Legal Studies, 31(S1), S205–S235.

Guzman, A.T., & Simmons, B.A. (2005). Power plays and capacity constraints: The selection of defendants in world trade organization disputes. The Journal of Legal Studies, 34(2), 557–598.

Hall, R.L., & Deardorff, A.V. (2006). Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review, 100(1), 69–84.

Hanegraaff, M., Beyers, J., Braun, C. (2011). Open the door to more of the same? The development of interest group representation at the WTO. World Trade Review, 10(4), 447–472.

Helpman, E., Melitz, J.M., Yeaple, R.S. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316.

Henisz, W.J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics & Politics, 12(1), 1–31.

Hillman, A.J., Keim, G.D., Schuler, D. (2004). Corporate political activity: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 30(6), 837–857.

Hiscox, M.J. (2002). International trade and political conflict: Commerce, coalitions, and mobility. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Horn, H., & Mavroidis, P.C. (2011). TheWTO dispute settlement data set, 1995–2011. In Data available at the World Bank data archive.

Horn, H., Mavroidis, P.C., Nordström, H., et al. (1999). Is the use of the WTO dispute settlement system biased? Vol. 2340. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Hudec, R.E. (1993). Enforcing international trade law: The evolution of the modern GATT legal system. Salem: Butterworth Legal Publishers.

Keisuke, I. (2006). Legalization and Japan: The politics of WTO dispute settlement. Cameron May.

Jensen, J.B., Quinn, D.P., Weymouth, S. (2015). The influence of firm global supply chains and foreign currency undervaluations on US trade disputes. International Organization, 69(04), 913– 947.

Johns, L., & Pelc, K.J. (2014). Who gets to be in the room? Manipulating participation in WTO disputes. International Organization, 68(03), 663–699.

Kim, M. (2008). Costly procedures: Divergent effects of legalization in the GATT/WTO dispute settlement procedures. International Studies Quarterly, 52(3), 657–686.

Kim, M. (2016). Enduring trade disputes: Disguised protectionism and duration and recurrence of international trade disputes. The Review of International Organizations, 11(3), 283–310.

Kim, I.S. (2017). Political cleavages within industry: Firm-level lobbying for trade liberalization. American Political Science Review, 111(1), 1–20.

Kreps, D.M., & Wilson, R. (1982). Reputation and imperfect information. Journal of Economic Theory, 27(2), 253–279.

Mansfield, E.D., & Bronson, R. (1997). Alliances, preferential trading arrangements, and international trade. American Political Science Review, 91(1), 94–107.

Mansfield, E.D., & Reinhardt, E. (2003). Multilateral determinants of regionalism: The effects of GATT/WTO on the formation of preferential trading arrangements. International Organization, 57(4), 829–862.

Mansfield, E.D., Milner, H.V., Rosendorff, B.P. (2000). Free to trade: Democracies, autocracies, and international trade. American Political Science Review, 94(02), 305–321.

Marshall, M.G., & Jaggers, K. (2014). Polity IV Project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2013. College Park, MD: University of Maryland. Available at: http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html. Accessed 1 April 2016.

McGillivray, F. (2004). Privileging industry: The comparative politics of trade and industrial policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Melitz, M.J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Milner, H.V. (1988). Resisting protectionism: Global industries and the politics of international trade. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Milner, H.V. (1997). Interests, institutions, and information: Domestic politics and international relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Milner, H.V., & Yoffie, D.B. (1989). Between free trade and protectionism: Strategic trade policy and a theory of corporate trade demands. International Organization, 43(02), 239–272.

Morrow, J.D., Siverson, R.M., Tabares, T.E. (1998). The political determinants of international trade: The major powers, 1907–1990. American Political Science Review, 92(3), 649–661.

Nucor, N. (2008). Lobbying report. https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=B9B25B19-A74F-4FE1-A720-EA336F383356&filingTypeID=51. Accessed 1 May 2016.

O’Halloran, S. (1994). Politics, process, and american trade policy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Pauwelyn, J. (2000). Enforcement and countermeasures in the WTO: Rules are rules-toward a more collective approach. American Journal of International Law, 94(2), 335–347.

Pelc, K.J. (2014). The politics of precedent in international law: A social network application. American Political Science Review, 108(3), 547–564.

Pervez, F. (2015). Waiting for election season: The timing of international trade disputes. The Review of International Organizations, 10(2), 265–303.

Poletti, A., De Bièvre, D., Hanegraaff, M. (2016). WTO judicial politics and EU trade policy: Business associations as vessels of special interest? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(1), 196–215.

Reinhardt, E. (2001). Adjudication without enforcement in GATT disputes. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(2), 174–195.

Rosendorff, B.P. (2005). Stability and rigidity: Politics and design of the WTO’s dispute settlement procedure. American Political Science Review, 99(03), 389–400.

Sattler, T., & Bernauer, T. (2011). Gravitation or discrimination? Determinants of litigation in the world trade organisation. European Journal of Political Research, 50(2), 143–167.

Schnakenberg, K.E. (2017). Informational lobbying and legislative voting. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 129–145.

Shaffer, G. (2003). Defending interests: Public-private partnerships in WTO litigation. Washington: Brookings Institution.

Shaffer, G. (2006). What’s new in EU trade dispute settlement? Judicialization, public–private networks and the WTO legal order. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(6), 832–850.

Stone, R.W. (2011). Controlling institutions: International organizations and the global economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

USTR, U. (2012). National trade estimate report on foreign trade barriers in 2012. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/India_0.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2016.

Weymouth, S. (2012). Firm lobbying and influence in developing countries: A multilevel approach. Business and Politics, 14(4), 1–26.

Woll, C., & Artigas, A. (2007). When trade liberalization turns into regulatory reform: The impact on business?government relations in international trade politics. Regulation & Governance, 1(2), 121–138.

Yildirim, A.B., Chatagnier, J.T., Poletti, A., Bièvre D.D. (2018). The internationalization of production and the politics of compliance in WTO disputes. The Review of International Organizations, 13(1), 49–75.

Zangl, B. (2008). Judicialization matters! A comparison of dispute settlement under GATT and the WTO. International Studies Quarterly, 52(4), 825–854.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for comments received at PEIO, APSA and Harvard University, and particularly wish to thank Ida Bastiaens, Ryan Brutger, In Song Kim, Michal Parízek, Anton Strezhnev, Simon Wuethrich, and three anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ryu, J., Stone, R.W. Plaintiffs by proxy: A firm-level approach to WTO dispute resolution. Rev Int Organ 13, 273–308 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9304-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9304-9