Abstract

Background

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common malady in women. Numerous nonsurgical treatments are available, each associated with risk of adverse events (AEs).

Methods

We systematically reviewed nonsurgical interventions for urgency, stress, or mixed UI in women, focusing on AEs. We searched MEDLINE®, Cochrane Central Trials Registry, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Embase® through December 4, 2017. We included comparative studies and single-group studies with at least 50 women. Abstracts were screened independently in duplicate. One researcher extracted study characteristics and results with verification by another independent researcher. When at least four studies of a given intervention reported the same AE, we conducted random effects model meta-analyses of proportions. We also assessed the strength of evidence.

Results

There is low strength of evidence that AEs are rare with behavioral therapies and neuromodulation, and that periurethral bulking agents may result in erosion and increase the risk of voiding dysfunction. High strength of evidence finds that anticholinergics and alpha agonists are associated with high rates of dry mouth and constitutional effects such as fatigue and gastrointestinal complaints. Onabotulinum toxin A (BTX) is also associated with increased risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs) and voiding dysfunction (moderate strength of evidence).

Discussion

Behavioral therapies and neuromodulation have low risk of AEs. Anticholinergics and alpha agonists have high rates of dry mouth and constitutional effects. BTX is associated with UTIs and voiding dysfunction. Periurethral bulking agents are associated with erosion and voiding dysfunction. These AEs should be considered when selecting appropriate UI treatment options. AE reporting is inconsistent and AE rates across studies tended to vary widely. Trials should report AEs more consistently.

Similar content being viewed by others

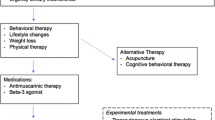

Numerous nonsurgical interventions are available to improve the symptoms of urinary incontinence (UI) for women, including both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic options. Most available nonsurgical options effectively achieve symptomatic cure (resolution of incontinence) or improvement.1 Behavioral therapies are generally more effective than other treatments to achieve cure or improvement, but the relative effectiveness of other interventions is less clear.1 While relief or improvement of UI symptoms may be the most important consideration for most women when selecting treatment,2,3,4,5 many women also consider the balance between treatment benefits and the risks, severity, or types of adverse events (AEs) that may occur.6 According to one survey, women with UI, in fact, put more emphasis on limiting the risk of side effects than on improving symptoms, in contrast with physicians who put more emphasis on increasing benefits.2

We conducted a broad systematic review of the clinical effects and harms of all nonsurgical treatments for typical stress, urgency, and mixed UI in nonpregnant women.7 Here we summarize findings regarding AEs. We have separately summarized comparative effectiveness for cure and improvement.1

METHODS

The Brown Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) conducted this review based on a systematic review of the scientific literature, using established methodologies.8 The PROSPERO registration number is CRD42017069903. The literature search and screening methodology, overall eligibility criteria, strength of evidence, and interpretation of findings are described in the full report.7 In brief, the review was an update of a prior systematic review conducted in 2012.9 We updated the review of adverse events through December 4, 2017. We included studies of adult women with stress, urgency, or mixed UI, excluding pregnant, hospitalized, or institutionalized women and those with UI attributable to urinary tract infection (UTI) or neurogenic bladder. We included pharmacological and nonpharmacological (but nonsurgical) interventions. We included randomized controlled trials with no minimum sample size and nonrandomized comparative studies with at least 50 women per intervention group. All studies had to have a minimum 4 weeks of follow-up.

DATA ANALYSIS

We calculated and summarized the percentage of people receiving each intervention who reported each AE as defined by the individual studies. We conducted restricted maximum likelihood meta-analyses of the arcsine of the square root proportions for AEs reported by at least four studies for a given intervention,10 regardless of the degree of statistical heterogeneity. The degree of heterogeneity was taken into consideration when evaluating the strength of evidence for each conclusion.

STRENGTH OF EVIDENCE

We graded the strength of the total body of evidence as per the AHRQ Methods Guide on assessing the strength of evidence.11 We assessed the strength of evidence for each outcome category (UI outcomes1 and adverse events). For each strength of evidence assessment, we considered the number of studies, their study designs, the study limitations (i.e., risk of bias and overall methodological quality), the directness of the evidence to the Key Questions, the consistency of study results, the precision of any estimates of effect, the likelihood of reporting bias, other limitations, and the overall findings across studies. Based on these assessments, we assigned a strength of evidence rating as being either high, moderate, or low, or there being insufficient evidence to estimate an effect.

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

This topic was nominated and funded by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) for systematic review by an EPC in partnership with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). AHRQ and PCORI program officers provided comments on draft versions of the protocol and full evidence report.7 PCORI and AHRQ did not directly participate in the literature search; determination of study eligibility criteria; data analysis or interpretation; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for publication.

RESULTS

The update searches returned 7840 new citations, of which we excluded 7117 during abstract screening (Fig. 1). Of the 723 abstracts accepted by initial screen and retrieved for full-text review, 613 were found to be irrelevant, primarily because they did not include the population of interest. Other reasons are listed in Figure 1. The 109 new studies were combined with the 134 studies from the original report that met eligibility criteria. Of these, 138 reported on AEs.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149 Across the 138 studies, analyzed sample sizes ranged between 6 and 4913, with a median of 123 (IQR 48 to 239). Sixty-five (47%) studies reported industry funding.

ADVERSE EVENTS

A wide range of AEs were reported, but studies were inconsistent in how and which AEs were reported. AE reporting was common among studies of anticholinergics, but sparser in studies of nonpharmacologic and other pharmacologic interventions. Excluding evaluations of vague AE outcomes (e.g., “adverse event,” “serious adverse event”), only for four active intervention categories—five anticholinergics, the alpha agonist duloxetine, BTX, and periurethral bulking agents—did at least four studies report the same sets of outcomes; these are summarized in Table 1 (with more details in Supplement Tables 1 to 3). Notably, across studies, there were wide ranges of reported frequencies for most AEs, with correspondingly large statistical heterogeneity. In Table 1, less heterogeneous estimates (I2 < 75%) are highlighted in italicized text.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

Fifty-two studies reported on AEs in studies of nonpharmacological interventions (Supplement Table 1).12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63 For no nonpharmacologic intervention did four of more studies report the same outcome. In general, the percentages of women with AEs were low. AE reporting was most common among studies of PFMT and TENS; 21 of 24 studies of PFMT and 7 of 11 studies of TENS reported no AEs. In three studies of TENS, between 10 and 18% of women reported a UTI.15, 46, 50 No other specific outcome was reported by more than two studies for any intervention.

PHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

There were 105 studies that reported on AEs in drugs (Supplement Table 2), 61 of which evaluated AEs in anticholinergics.45,46,47,48, 64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120 In total, 71 studies reported on other drugs and placebo arms.48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83, 114,115,116,117,118, 120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149 For most pharmacological interventions, “serious” AEs (as described by authors) were rare or did not occur, although few studies defined serious AEs. However, with periurethral bulking agents, 4.7% of 362 women in three studies had serious AEs,137, 147, 149 including erosion and need for surgical excision of the bulking agents. The one study of a periurethral bulking agent currently available in the USA (macroplastique) reported 1.6% rate of erosion.147 In seven studies of anticholinergics, overall 2.2% of 2469 women had serious AEs,114,115,116,117,118,119,120 although the AEs were mostly undefined. In two studies, 0.6% of 1390 women taking the alpha agonist duloxetine had (undefined) serious AEs.136, 138 By comparison, in 10 studies,61,62,63, 115,116,117,118, 136,137,138 1.0% of 2695 women taking placebo (or no treatment) had (mostly undefined) serious AEs.

The most commonly reported AE across interventions was dry mouth (Table 1). Approximately one-quarter or more of women using anticholinergic medications reported dry mouth; the summary estimate for oxybutynin was 44% (95% CI 31, 58) across 25 studies, but 24% (95% CI 15, 35) for tolterodine across 17 studies, with similar estimates for fesoterodine (5 studies), solifenacin (4 studies), and trospium (4 studies). In contrast, in 24 placebo arms, the summary estimate for placebo was 8% (95% CI 4, 12). Among 15 studies of the alpha agonist duloxetine, approximately 13% (95% CI 9, 16) complained of dry mouth. However, studies were highly heterogeneous, with within-study estimates ranging from 0 to 100% across studies (including placebo arms) and meta-analysis I2 statistics all ≥ 92%.

Constipation was also commonly reported. For three anticholinergics—oxybutynin (19 studies), solifenacin (4 studies), and tolterodine (14 studies)—and duloxetine (14 studies), summary estimates of rates of constipation ranged from 8% (95% CI 4, 14) with tolterodine to 15% (95% CI 7, 26) for solifenacin, with lower rates among women given placebo (3%; 95% CI 2, 5; across 34 studies). Again, statistical heterogeneity was very wide, with within-study estimates ranging from 0 to 50% and I2 statistics all ≥ 88%.

Other common AEs with anticholinergics, specifically oxybutynin, included summary estimates of voiding dysfunction/urinary retention in 16% (95% CI 8, 27; 6 studies) of women and visual AEs (mostly blurring) in 11% (95% CI 6, 18; 15 studies) of women, again with wide ranges of estimates across studies. Other common AEs with duloxetine included fatigue (summary estimate 10%; 95% CI 7, 13; 13 studies), nausea (19%; 95% CI 13, 26; 15 studies), and headache (11%, 95% CI 8, 14; 11 studies), also with wide ranges of estimates across studies.

Drug discontinuation rates were generally higher with duloxetine (20%; 95% CI 14, 26; 5 studies) and oxybutynin (10%; 95% CI 4, 18; 6 studies) than for tolterodine (4.6%; 95% CI 3.4, 6.0; 5 studies) or placebo (3.3%; 95% CI 2.5, 4.3; 10 studies).

Only six studies reported on AEs with bladder BTX.50, 114, 139,140,141,142 All six reported on UTIs, with a wide range across studies (17 to 55%) and a summary estimate of 35% (95% CI 29, 43). UTIs were lower among those receiving periurethral bulking (7.5%; 95% CI 3.5, 13; 5 studies) or placebo (6.4%; 95% CI 2.7, 12; 12 studies).

The most commonly reported AE for the periurethral bulking agents was UTI in five studies (7.5%; 95% CI 3.5, 12.8)137, 143,144,145,146 and urinary retention/voiding dysfunction in eight studies (6.9%; 95% CI 0.6, 19.5),137, 143,144,145,146,147,148,149 both sets of outcomes had wide ranges across studies. However, only one of these studies, with 122 women,137 evaluated a periurethral bulking agent currently available in the USA (macroplastique). This study found high rates of UTI (24%), headache (18%), and urinary retention/dysuria (16%). Serious AEs (erosion) were low (1.6%), as were pain (5%) and yeast infection (2.5%). All other single and combination medications were evaluated in only one or two studies each.

DISCUSSION

Although a large number of studies have evaluated AEs of interventions for urgency, stress, and mixed UI in women, the evidence regarding these outcomes is generally sparse or poor because of important limitations to the corpus of studies. Studies tend to be very inconsistent in how, and which, AEs are reported. In relatively few instances did at least four studies that compared similar interventions report common AE outcomes. Furthermore, there is extensive large statistical heterogeneity in estimates of AEs, suggesting intrinsic differences across studies either how AEs were defined, how AE data were collected, and possibly intrinsic differences across study participants. Thus, there are few definitive conclusions that can be made about the rates of AEs with the various interventions.

Low strength of evidence suggests that (first-line) behavioral therapy rarely results in AEs. AEs are more common with (second-line) pharmacologic interventions. There is high strength of evidence that anticholinergics and alpha agonists commonly cause symptomatic dry mouth, and moderate strength of evidence that alpha agonists result in a range of constitutional symptoms such as nausea, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, dizziness, and headache. For third-line interventions, there is low strength of evidence that AEs were rare with TENS and that periurethral bulking agents result in serious AEs, including erosion and need for surgical excision, in a small percentage of patients. Moderate strength of evidence suggests that the most commonly reported AEs with BTX were UTI and urinary retention (voiding dysfunction). Low strength of evidence also suggested high rates of UTI and urinary retention with periurethral bulking agents. Precise estimates of most AE rates are not available due to the wide range in event rates across studies.

The choice of which treatment option is “best” for a particular woman with UI will vary depending on her symptoms, the severity of those symptoms, her history of prior treatments, treatment goals, preferences, and values regarding the types of treatments she is willing to undergo, and also the AE risks she is willing to assume. For example, some women may prefer a “simple” daily pill that can be stopped at any time, accepting the risk of dryness and constitutional complaints. Other women may prefer TENS, which has lower risk of symptoms but requires ongoing clinic visits. Yet other women may prefer BTX, which can be given infrequently but risks urinary dysfunction. Of note, among studies that have evaluated women’s thoughts about what defines successful treatment, women tended to balance the potential benefits of treatment with their risks and the severity or types of adverse events that may occur. When considering medications, women thought it was important to reduce symptoms without side effects.6 A survey of patients and clinicians found that the patients put more emphasis on limiting the risk of side effects than on improving symptoms, in contrast with physicians who put more emphasis on increasing benefits.2

Nevertheless, there is strong to moderate evidence that behavioral therapies, including bladder training, biofeedback, pelvic floor muscle training, and others, are most effective in achieving cure or improvement,1 with low strength of evidence of rare AEs. Supplement Table 4 summarizes findings from this and the article regarding clinical outcomes and AEs. This information can form the basis of a guide for clinicians and their patients when considering different treatment options. Overall, the results of our review are consistent with a range of UI guidelines from six international medical organizations,150 supporting the use of conservative treatments including behavioral therapy and physical therapy, electroacupuncture, anticholinergic medications, beta-agonists, BTX, and sacroneuromodulation.

LIMITATIONS ACROSS THE EVIDENCE BASE

The major limitation identified by this review is the relative dearth of evidence based on the non-standardized reporting and complexity of AE information reported across studies. Studies neither consistently reported AEs nor used standard terminology, limiting our ability to attain complete and unbiased estimates of AE frequency. In particular, AE rates were generally inconsistent, resulting in wide ranges of estimates and very large statistical heterogeneity across studies. The most likely reason for the heterogeneity are differing definitions and thresholds used across studies and different modes of collecting AE data (i.e., actively asking about specific AEs versus passively asking about “any” AE or only including what was reported by patients to their clinicians). Reporting on these factors was minimal.

LIMITATIONS OF THE ANALYTIC APPROACH

Despite large statistical and thus likely clinical heterogeneity across studies, we chose to conduct and report the meta-analyzed estimates to better allow indirect comparisons across interventions. Given the large heterogeneity of many AE rates, with I2 commonly > 90%, the provided median and range of estimates across studies may be considered to be more reliable. We did not contact authors for additional data or definitions of their terminology.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

There is a need to standardize AE reporting. If all studies had consistently and similarly reported these outcomes, our summary findings would be much more robust. Implementation and consistent use of standardized AE reporting would be immensely helpful and would improve reporting and comparisons for future systematic reviews. At a minimum, all trialists should pre-specify and report expected adverse events among outcomes to be evaluated and should incorporate methods to collect data on unexpected adverse events. All adverse events should be reported numerically (with numerators and denominators) for each intervention arm, including zero events for any expected adverse event.151 Trialists are strongly encouraged not only to register their protocols, but also to report complete results data, including adverse events, at registries such as ClinicalTrials.gov.152

CONCLUSIONS

Overall information regarding possible AEs are limited due to inconsistent reporting, and the complexity of comparing the variable underlying disease severity and disparate outcomes reported. First-line behavioral interventions were found to have low risk of AEs. Second-line pharmacological interventions are associated with non-serious but bothersome AEs, such as dry mouth, nausea, and fatigue. Third-line interventions are associated with increased risk of UTIs and voiding dysfunction. As noted in the companion article,1 most examined active intervention categories appear to be better than sham or no treatment to achieve cure or improvement. Large gaps remain in the literature regarding the comparison of individual interventions, and future studies should report subgroup analyses based on UI type and severity and prior treatment history. For clinicians, patients, and payers to make informed decisions, specifically for patient subgroups with sparse evidence, new evidence from studies comparing interventions with standardized outcomes is needed.

References

Balk EM, Rofeberg V, Adam GP, et al. Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170(7):465-479. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-3227.

Heisen M, Baeten SA, Verheggen BG, et al. Patient and physician preferences for oral pharmacotherapy for overactive bladder: two discrete choice experiments. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32:787–96. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2016.1142959.

Cardozo L, Hall T, Ryan J, et al. Safety and efficacy of flexible-dose fesoterodine in British subjects with overactive bladder: insights into factors associated with dose escalation. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:1581–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1804-1.

Lee KS, Lee YS, Kim JC, et al. Patient-reported goal achievement after antimuscarinic treatment in patients with overactive bladder symptoms. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:663–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02951.x.

Cartwright R, Srikrishna S, Cardozo L, et al. Validity and reliability of patient selected goals as an outcome measure in overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:841–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-011-1360-0.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp Z, et al. Assessing patients’ descriptions of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and perspectives on treatment outcomes: results of qualitative research. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:1260–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02450.x.

Balk E, Adam GP, Kimmel H, et al. Nonsurgical Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Systematic Review Update. (Prepared by the Brown Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290–2015-00002-I for AHRQ and PCORI.) AHRQ Publication No. 18-EHC016-EF. PCORI Publication No. 2018-SR-03. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; August 2018. Available at: https://doi.org/10.23970/AHRQEPCCER212. Accessed 5 March 2019.

Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. January 2014. Chapters available at: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/research-methods. Accessed 5 March 2019.

Shamliyan T, Wyman J, Kane RL. Nonsurgical Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Adult Women: Diagnosis and Comparative Effectiveness. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 36. (Prepared by the University of Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA 290–2007-10064-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-EHC074- EF. Rockville, MD. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2012. Available at: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/urinary-incontinence-treatment/research. Accessed March 5, 2019.

Trikalinos TA, Hoaglin DC, Schmid CH. Empirical and Simulation-Based Comparison of Univariate and Multivariate Meta-Analysis for Binary Outcomes. Methods Research Report. (Prepared by the Tufts Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290–2007-10055-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC066-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2013. Available at: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/methods-binary-outcomes-evaluation/research. Accessed 5 March 2019.

Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari M, et al. Grading the Strength of a Body of Evidence When Assessing Health Care Interventions for the Effective Health Care Program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Update. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (Prepared by the RTI-UNC Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290–2007-10056-I). AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC130-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2013. Available at: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/methods-guidance-grading-evidence/methods. Accessed 5 March 2019.

Abdelbary AM, El-Dessoukey AA, Massoud AM, et al. Combined Vaginal Pelvic Floor Electrical Stimulation (PFS) and Local Vaginal Estrogen for Treatment of Overactive Bladder (OAB) in Perimenopausal Females. Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). Urology. 2015;86:482–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2015.06.007.

Alves PG, Nunes FR, Guirro EC. Comparison between two different neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocols for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Bras Fis 2011;15:393–8.

Baker J, Costa D, Guarino JM, et al. Comparison of mindfulness-based stress reduction versus yoga on urinary urge incontinence: a randomized pilot study. with 6-month and 1-year follow-up visits. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:141–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/spv.0000000000000061.

Beer GM, Gurule MM, Komesu YM, et al. Cycling Versus Continuous Mode In Neuromodulator Programming: A Crossover, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Urol Nurs 2016;36:123–32.

Betschart C, Mol SE, Lutolf-Keller B, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence: a comparison of outcomes in premenopausal versus postmenopausal women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:219–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0b013e31829950e5.

Castellani D, Saldutto P, Galica V, et al. Low-Dose Intravaginal Estriol and Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in Post-Menopausal Stress Urinary Incontinence. Urol Int 2015;95:417–21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381989.

de Souza Abreu N, de Castro Villas Boas B, Netto JM, et al. Dynamic lumbopelvic stabilization for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women: Controlled and randomized clinical trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:2160–2168. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23261.

Ferreira M, Santos PC. Impact of exercise programs in woman's quality of life with stress urinary incontinence. Rev Port Saúde Pública 2012;30:3–10.

Fitz FF, Stupp L, da Costa TF, et al. Outpatient biofeedback in addition to home pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn 2017; 36:2034–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23226.

Galea MP, Tisseverasinghe S, Sherburn M. A randomised controlled trial of transabdominal ultrasound biofeedback for pelvic floor muscle training in older women with urinary incontinence. Aust N Z Continence J 2013;19:38-44.

Gozukara YM, Akalan G, Tok EC, et al. The improvement in pelvic floor symptoms with weight loss in obese women does not correlate with the changes in pelvic anatomy. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:1219–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2368-z.

Hirakawa T, Suzuki S, Kato K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training with or without biofeedback for urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:1347–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-2012-8.

Huebner M, Riegel K, Hinninghofen H, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence: a randomized, controlled trial comparing different conservative therapies. Physiother Res Int 2011;16:133–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.489.

Jha S, Walters SJ, Bortolami O, et al. Impact of pelvic floor muscle training on sexual function of women with urinary incontinence and a comparison of electrical stimulation versus standard treatment (IPSU trial): a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2017; 104:91–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2017.06.003.

Kaya S, Akbayrak T, Beksac S. Comparison of different treatment protocols in the treatment of idiopathic detrusor overactivity: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2011;25:327–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215510385481.

Kaya S, Akbayrak T, Gursen C, et al. Short-term effect of adding pelvic floor muscle training to bladder training for female urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J 2015;26:285–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2517-4.

Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1124–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1210627.

Leong BS, Mok NW. Effectiveness of a new standardised Urinary Continence Physiotherapy Programme for community-dwelling older women in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21:30–7. https://doi.org/10.12809/hkmj134185.

Manonai J, Kamthaworn S, Petsarb K, et al. Development of a pelvic floor muscle strength evaluation device. J Med Assoc Thail 2015;98:219–25.

McLean L, Varette K, Gentilcore-Saulnier E, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training in women with stress urinary incontinence causes hypertrophy of the urethral sphincters and reduces bladder neck mobility during coughing. Neurourol Urodyn 2013;32:1096–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22343.

Oldham J, Herbert J, McBride K. Evaluation of a new disposable “tampon like” electrostimulation technology (Pelviva(R)) for the treatment of urinary incontinence in women: a 12-week single blind randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn 2013;32:460–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22326.

Olmo Carmona MV, González Molleja ÁM, Luque Ríos I, et al. Neuroestimulación percutánea del nervio tibial posterior frente a neuroestimulación de B 6 (Sanyinjiao) en incontinencia urinaria de urgencia. Rev Int Acupuntura 2013;7:124–30.

Pereira VS, de Melo MV, Correia GN, et al. Long-term effects of pelvic floor muscle training with vaginal cone in post-menopausal women with urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn 2013;32:48–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22271.

Peters KM, Shen L, McGuire M. Effect of Sacral Neuromodulation Rate on Overactive Bladder Symptoms: A Randomized Crossover Feasibility Study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2013;5:129–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12000.

Porta-Roda O, Vara-Paniagua J, Diaz-Lopez MA, et al. Effect of vaginal spheres and pelvic floor muscle training in women with urinary incontinence: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;34:533–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22640.

Resnick NM, Perera S, Tadic S, et al. What predicts and what mediates the response of urge urinary incontinence to biofeedback? Neurourol Urodyn 2013;32:408–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22347.

Segal S, Morse A, Sangal P, et al. Efficacy of FemiScan Pelvic Floor Therapy for the Treatment of Urinary Incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2016;22:433–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/spv.0000000000000307.

Sherburn M, Bird M, Carey M, et al. Incontinence improves in older women after intensive pelvic floor muscle training: an assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30:317–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20968.

Siegel S, Noblett K, Mangel J, et al. Three-year Follow-up Results of a Prospective, Multicenter Study in Overactive Bladder Subjects Treated With Sacral Neuromodulation. Urology. 2016;94:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.04.024.

Sjostrom M, Umefjord G, Stenlund H, et al. Internet-based treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomised controlled study with focus on pelvic floor muscle training. BJU Int 2013;112:362–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11713.x.

Sran M, Mercier J, Wilson P, et al. Physical therapy for urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or low bone density: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2016;23:286–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0000000000000594.

Wang S, Lv J, Feng X, et al. Efficacy of Electrical Pudendal Nerve Stimulation versus Transvaginal Electrical Stimulation in Treating Female Idiopathic Urgency Urinary Incontinence. J Urol 2017;197:1496–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.065.

Yamanishi T, Suzuki T, Sato R, et al. Effects of magnetic stimulation on urodynamic stress incontinence refractory to pelvic floor muscle training in a randomized sham-controlled study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 2017;11:61–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12197.

Kafri R, Deutscher D, Shames J, et al. Randomized trial of a comparison of rehabilitation or drug therapy for urgency urinary incontinence: 1-year follow-up. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:1181–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1992-8.

Ozdedeli S, Karapolat H, Akkoc Y. Comparison of intravaginal electrical stimulation and trospium hydrochloride in women with overactive bladder syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil 2010;24:342–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509346092.

Peters KM, Macdiarmid SA, Wooldridge LS, et al. Randomized trial of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation versus extended-release tolterodine: results from the overactive bladder innovative therapy trial. J Urol 2009;182:1055–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.045.

Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1995–2000.

Ahlund S, Nordgren B, Wilander EL, et al. Is home-based pelvic floor muscle training effective in treatment of urinary incontinence after birth in primiparous women? A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:909–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12173.

Amundsen CL, Richter HE, Menefee SA, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA vs Sacral Neuromodulation on Refractory Urgency Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316:1366–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.14617.

Kim H, Yoshida H, Suzuki T. Effects of exercise treatment with or without heat and steam generating sheet on urine loss in community-dwelling Japanese elderly women with urinary incontinence. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2011;11:452–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00705.x.

Lim R, Liong ML, Leong WS, et al. Pulsed Magnetic Stimulation for Stress Urinary Incontinence: 1-Year Followup Results. J Urol 2017;197:1302–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.11.091.

Liu Z, Liu Y, Xu H, et al. Effect of Electroacupuncture on Urinary Leakage Among Women With Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317:2493–501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7220.

Lovatsis D, Best C, Diamond P. Short-term Uresta efficacy (SURE) study: a randomized controlled trial of the Uresta continence device. Int Urogynecol J 2017;28:147–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3090-9.

Pereira VS, Bonioti L, Correia GN, et al. [Effects of surface electrical stimulation in older women with stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled pilot study]. Actas Urol Esp 2012;36:491–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuro.2011.11.016.

Samuelsson E. Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence Via Smartphone; 2017. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01848938. Accessed 5 March 2019.

Solberg M, Alraek T, Mdala I, et al. A pilot study on the use of acupuncture or pelvic floor muscle training for mixed urinary incontinence. Acupunct Med 2016;34:7–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2015-010828.

Terlikowski R, Dobrzycka B, Kinalski M, et al. Transvaginal electrical stimulation with surface-EMG biofeedback in managing stress urinary incontinence in women of premenopausal age: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:1631–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2071-5.

Wallis MC, Davies EA, Thalib L, et al. Pelvic static magnetic stimulation to control urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Med Res 2012;10:7–14. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2011.1008.

Wiegersma M, Panman CM, Kollen BJ, et al. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training compared with watchful waiting in older women with symptomatic mild pelvic organ prolapse: randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ. 2014;349:g7378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7378.

Abdulaziz K, Hasan T. Role of pelvic floor muscle therapy in obese perimenopausal females with stress incontinence: A randomized control trial. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2012;16:34–42.

Cornu JN, Mouly S, Amarenco G, et al. 75NC007 device for noninvasive stress urinary incontinence management in women: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:1727–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1814-z.

Xu H, Liu B, Wu J, et al. A Pilot Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial of Electroacupuncture for Women with Pure Stress Urinary Incontinence. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150821. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150821.

Bray R, Cartwright R, Cardozo L, et al. Tolterodine ER reduced increased bladder wall thickness in women with overactive bladder. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel group study. Neurourol Urodyn 2017; 37:237–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23281.

Dmochowski RR, Davila GW, Zinner NR, et al. Efficacy and safety of transdermal oxybutynin in patients with urge and mixed urinary incontinence. J Urol 2002;168:580–6.

Dmochowski RR, Staskin DR, Duchin K, et al. Clinical safety, tolerability and efficacy of combination tolterodine/pilocarpine in patients with overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pract 2014;68:986–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12409.

DuBeau CE, Khullar V, Versi E. “Unblinding” in randomized controlled drug trials for urinary incontinence: Implications for assessing outcomes when adverse effects are evident. Neurourol Urodyn 2005;24:13–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20083.

Frenkl T, Railkar R, Shore N, et al. Evaluation of an experimental urodynamic platform to identify treatment effects: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in patients with overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn 2012;31:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.21094.

Gittelman M, Weiss H, Seidman L. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, efficacy and safety study of oxybutynin vaginal ring for alleviation of overactive bladder symptoms in women. J Urol 2014;191:1014–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.11.019.

Homma Y, Paick JS, Lee JG, et al. Clinical efficacy and tolerability of extended-release tolterodine and immediate-release oxybutynin in Japanese and Korean patients with an overactive bladder: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. BJU Int 2003;92:741–7.

Khullar V, Hill S, Laval KU, et al. Treatment of urge-predominant mixed urinary incontinence with tolterodine extended release: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Urology. 2004;64:269–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2004.02.029.

Klarskov N, Darekar A, Scholfield D, et al. Effect of fesoterodine on urethral closure function in women with stress urinary incontinence assessed by urethral pressure reflectometry. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:755–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2269-6.

McMichael J. Safety and Efficacy Study of a New Treatment for Symptoms of Urinary Incontinence; 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01340066. Accessed 5 March 2019.

Moore KH, Hay DM, Imrie AE, et al. Oxybutynin hydrochloride (3 mg) in the treatment of women with idiopathic detrusor instability. Br J Urol 1990;66:479–85.

Nelken RS, Ozel BZ, Leegant AR, et al. Randomized trial of estradiol vaginal ring versus oral oxybutynin for the treatment of overactive bladder. Menopause. 2011;18:962–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3182104977.

Orri M, Lipset CH, Jacobs BP, et al. Web-based trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tolterodine ER 4 mg in participants with overactive bladder: REMOTE trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2014;38:190–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.04.009.

Rogers R, Bachmann G, Jumadilova Z, et al. Efficacy of tolterodine on overactive bladder symptoms and sexual and emotional quality of life in sexually active women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:1551–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0688-6.

Sand PK, Dmochowski RR, Zinner NR, et al. Trospium chloride extended release is effective and well tolerated in women with overactive bladder syndrome. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2009;20:1431–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0969-8.

Swift S, Garely A, Dimpfl T, et al. A new once-daily formulation of tolterodine provides superior efficacy and is well tolerated in women with overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2003;14:50–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-002-1009-0.

Szonyi G, Collas DM, Ding YY, et al. Oxybutynin with bladder retraining for detrusor instability in elderly people: a randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing 1995;24:287–91.

Tapp AJ, Cardozo LD, Versi E, et al. The treatment of detrusor instability in post-menopausal women with oxybutynin chloride: a double blind placebo controlled study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990;97:521–6.

Thuroff JW, Bunke B, Ebner A, et al. Randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial on treatment of frequency, urgency and incontinence related to detrusor hyperactivity: oxybutynin versus propantheline versus placebo. J Urol 1991;145:813–6.

Zinner N, Tuttle J, Marks L. Efficacy and tolerability of darifenacin, a muscarinic M3 selective receptor antagonist (M3 SRA), compared with oxybutynin in the treatment of patients with overactive bladder. World J Urol 2005;23:248–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-005-0507-3.

Anderson RU, Mobley D, Blank B, et al. Once daily controlled versus immediate release oxybutynin chloride for urge urinary incontinence. OROS Oxybutynin Study Group. J Urol. 1999;161:1809–12.

Anderson RU, MacDiarmid S, Kell S, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of extended-release oxybutynin vs extended-release tolterodine in women with or without prior anticholinergic treatment for overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2006;17:502–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-005-0057-7.

Appell RA. Clinical efficacy and safety of tolterodine in the treatment of overactive bladder: a pooled analysis. Urology. 1997;50(6A Suppl):S90–6.

Armstrong RB, Luber KM, Peters KM. Comparison of dry mouth in women treated with extended-release formulations of oxybutynin or tolterodine for overactive bladder. Int Urol Nephrol 2005;37:247–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-004-4703-7.

Aziminekoo E, Ghanbari Z, Hashemi S, et al. Oxybutynin and tolterodine in a trial for treatment of overactive bladder in Iranian women. J Family Reprod Health 2014;8:73–6.

Bodeker RH, Madersbacher H, Neumeister C, et al. Dose escalation improves therapeutic outcome: post hoc analysis of data from a 12-week, multicentre, double-blind, parallel-group trial of trospium chloride in patients with urinary urge incontinence. BMC Urol 2010;10:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-10-15.

But I, Goldstajn MS, Oreskovic S. Comparison of two selective muscarinic receptor antagonists (solifenacin and darifenacin) in women with overactive bladder--the SOLIDAR study. Coll Antropol 2012;3:1347–53.

Butt F, Badar N, Rana M. Comparison of Side Effects of Solifenacin Vs Tolteridine in Patients with Urinary Incontinence. Pakistan J Med Health Sci 2016;10:590–3.

Chapple C, van Kerrebroeck P, Tubaro A, et al. Clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability of once-daily fesoterodine in subjects with overactive bladder. Eur Urol 2007;52:1204–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.07.009.

Chu FM, Dmochowski RR, Lama DJ, et al. Extended-release formulations of oxybutynin and tolterodine exhibit similar central nervous system tolerability profiles: a subanalysis of data from the OPERA trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:1849–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.036.

Chughtai B, Forde JC, Buck J, et al. The concomitant use of fesoterodine and topical vaginal estrogen in the management of overactive bladder and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Post Reprod Health 2016;22:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053369116633017.

Davila GW, Daugherty CA, Sanders SW. A short-term, multicenter, randomized double-blind dose titration study of the efficacy and anticholinergic side effects of transdermal compared to immediate release oral oxybutynin treatment of patients with urge urinary incontinence. J Urol 2001;166:140–5.

Dede H, Dolen I, Dede FS, et al. What is the success of drug treatment in urge urinary incontinence? What should be measured? Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;287:511–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2596-8.

Gameiro MO, Moreira EH, Gameiro FO, et al. Vaginal weight cone versus assisted pelvic floor muscle training in the treatment of female urinary incontinence. A prospective, single-blind, randomized trial. Int Urogynecol J 2010;21:395–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-1059-7.

Gupta SK, Sathyan G, Lindemulder EA, et al. Quantitative characterization of therapeutic index: application of mixed-effects modeling to evaluate oxybutynin dose-efficacy and dose-side effect relationships. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999;65:672–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-9236(99)90089-9.

Gupta SK, Sathyan G. Pharmacokinetics of an oral once-a-day controlled-release oxybutynin formulation compared with immediate-release oxybutynin. J Clin Pharmacol 1999;39:289–96.

Hess R, Huang AJ, Richter HE, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of questionnaire-based initiation of urgency urinary incontinence treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:244.e1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.008.

Jafarabadi M, Jafarabadi L, Shariat M, et al. Considering the prominent complaint as a guide in medical therapy for overactive bladder syndrome in women over 45 years. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:120–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.12483.

Kinjo M, Sekiguchi Y, Yoshimura Y, et al. Long-term Persistence with Mirabegron versus Solifenacin in Women with Overactive Bladder: Prospective, Randomized Trial. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2016; 10:148–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12151.

Lackner TE, Wyman JF, McCarthy TC, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the cognitive effect, safety, and tolerability of oral extended-release oxybutynin in cognitively impaired nursing home residents with urge urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:862–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01680.x.

Madersbacher H, Halaska M, Voigt R, et al. A placebo-controlled, multicentre study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of propiverine and oxybutynin in patients with urgency and urge incontinence. BJU Int 1999;84:646–51.

Milani R, Scalambrino S, Milia R, et al. Double-Blind Crossover Comparison of Flavoxate and Oxybutynin in Women Affected by Urinary Urge Syndrome. Int Urogynecol J 1993;4:3–8.

Preik M, Albrecht D, O'Connell M, et al. Effect of controlled-release delivery on the pharmacokinetics of oxybutynin at different dosages: severity-dependent treatment of the overactive bladder. BJU Int 2004;94:821–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05040.x.

Rogers RG, Bachmann G, Scarpero H, et al. Effects of tolterodine ER on patient-reported outcomes in sexually active women with overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2159–65. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990903103279.

Saks EK, Wiebe DJ, Cory LA, et al. Beliefs about medications as a predictor of treatment adherence in women with urinary incontinence. J Women's Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:440–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2952.

Salvatore S, Khullar V, Cardozo L, et al. Long-term prospective randomized study comparing two different regimens of oxybutynin as a treatment for detrusor overactivity. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005;119:237–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.07.042.

Sand PK, Miklos J, Ritter H, et al. A comparison of extended-release oxybutynin and tolterodine for treatment of overactive bladder in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2004;15:243–8.

Sand PK, Morrow JD, Bavendam T, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of fesoterodine in women with overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2009;20:827–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0857-2.

Zellner M, Madersbacher H, Palmtag H, et al. Trospium chloride and oxybutynin hydrochloride in a german study of adults with urinary urge incontinence: results of a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, flexible-dose noninferiority trial. Clin Ther 2009;31:2519–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.11.005.

Zimmern P, Litman HJ, Mueller E, et al. Effect of fluid management on fluid intake and urge incontinence in a trial for overactive bladder in women. BJU Int 2010;105:1680–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09055.x.

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al. Anticholinergic therapy vs. onabotulinumtoxina for urgency urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1803–13. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1208872.

Dmochowski RR, Sand PK, Zinner NR, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of transdermal oxybutynin and oral tolterodine versus placebo in previously treated patients with urge and mixed urinary incontinence. Urology. 2003;62:237–42.

Drutz HP, Appell RA, Gleason D, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of tolterodine compared to oxybutynin and placebo in patients with overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 1999;10:283–9.

Huang AJ, Hess R, Arya LA, et al. Pharmacologic treatment for urgency-predominant urinary incontinence in women diagnosed using a simplified algorithm: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:444.e1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.002.

Marencak J, Cossons NH, Darekar A, et al. Investigation of the clinical efficacy and safety of pregabalin alone or combined with tolterodine in female subjects with idiopathic overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn 2011;30:75–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20928.

Sung HH, Han DH, Kim TH, et al. Interventions do not enhance medication persistence and compliance in patients with overactive bladder: a 24 weeks, randomised, open-label, multi-center trial. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69:1309–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12705.

van Kerrebroeck P, Abrams P, Lange R, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of European and Canadian women with stress urinary incontinence. BJOG. 2004;111:249–57.

Balachandran A, Duckett J. The efficacy and tolerability of mirabegron in a non-trial clinical setting. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;200:63–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.030.

Bent AE, Gousse AE, Hendrix SL, et al. Duloxetine compared with placebo for the treatment of women with mixed urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2008;27:212–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20471.

Capobianco G, Donolo E, Borghero G, et al. Effects of intravaginal estriol and pelvic floor rehabilitation on urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;285:397–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-1955-1.

Cardozo L, Drutz HP, Baygani SK, et al. Pharmacological treatment of women awaiting surgery for stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:511–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000134525.86480.0f.

Castro-Diaz D, Palma PC, Bouchard C, et al. Effect of dose escalation on the tolerability and efficacy of duloxetine in the treatment of women with stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007;18:919–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0256-x.

Dmochowski RR, Miklos JR, Norton PA, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of North American women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol 2003;170:1259–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000080708.87092.cc.

Ghoniem GM, Van Leeuwen JS, Elser DM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine alone, pelvic floor muscle training alone, combined treatment and no active treatment in women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol 2005;173:1647–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000154167.90600.c6.

Hurley DJ, Turner CL, Yalcin I, et al. Duloxetine for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women: an integrated analysis of safety. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;125:120–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.08.006.

Kinchen KS, Obenchain R, Swindle R. Impact of duloxetine on quality of life for women with symptoms of urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2005;16:337–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-004-1270-5.

Lin AT, Sun MJ, Tai HL, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of women with stress predominant urinary incontinence in Taiwan: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Urol 2008;8:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-8-2.

Michel MC, Minarzyk A, Schwerdtner I, et al. Observational study on safety and tolerability of duloxetine in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence in German routine practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;75:1098–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04389.x.

Millard RJ, Moore K, Rencken R, et al. Duloxetine vs placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a four-continent randomized clinical trial. BJU Int 2004;93:311–8.

Norton PA, Zinner NR, Yalcin I, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:40–8.

Schagen van Leeuwen JH, Lange RR, Jonasson AF, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in elderly women with stress urinary incontinence or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence. Maturitas. 2008;60:138–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.04.012.

Steers WD, Herschorn S, Kreder KJ, et al. Duloxetine compared with placebo for treating women with symptoms of overactive bladder. BJU Int 2007;100:337–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06980.x.

Cardozo L, Lange R, Voss S, et al. Short- and long-term efficacy and safety of duloxetine in women with predominant stress urinary incontinence. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:253–61. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990903438295.

Ghoniem G, Corcos J, Comiter C, et al. Cross-linked polydimethylsiloxane injection for female stress urinary incontinence: results of a multicenter, randomized, controlled, single-blind study. J Urol 2009;181:204–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.032.

Robinson D, Abrams P, Cardozo L, et al. The efficacy and safety of PSD503 (phenylephrine 20%, w/w) for topical application in women with stress urinary incontinence. A phase II, multicentre, double-blind, placebo controlled, 2-way cross over study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;159:457–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.07.030.

Brubaker L, Richter HE, Visco A, et al. Refractory idiopathic urge urinary incontinence and botulinum A injection. J Urol 2008;180:217–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.028.

Dmochowski R, Chapple C, Nitti VW, et al. Efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA for idiopathic overactive bladder: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized, dose ranging trial. J Urol 2010;184:2416–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.021.

Jabs C, Carleton E. Efficacy of botulinum toxin a intradetrusor injections for non-neurogenic urinary urge incontinence: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:53–60.

Nitti VW, Ginsberg D, Sievert KD, et al. Durable Efficacy and Safety of Long-Term OnabotulinumtoxinA Treatment in Patients with Overactive Bladder Syndrome: Final Results of a 3.5-Year Study. J Urol 2016;196:791–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.03.146.

Lightner D, Rovner E, Corcos J, et al. Randomized controlled multisite trial of injected bulking agents for women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency: mid-urethral injection of Zuidex via the Implacer versus proximal urethral injection of Contigen cystoscopically. Urology. 2009;74:771–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.034.

Mohr S, Siegenthaler M, Mueller MD, et al. Bulking agents: an analysis of 500 cases and review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:241–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1834-8.

Mohr S, Marthaler C, Imboden S, et al. Bulkamid (PAHG) in mixed urinary incontinence: What is the outcome? Int Urogynecol J 2017;28:1657–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3332-5.

Sokol ER, Karram MM, Dmochowski R. Efficacy and safety of polyacrylamide hydrogel for the treatment of female stress incontinence: a randomized, prospective, multicenter North American study. J Urol 2014;192:843–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.03.109.

Futyma K, Miotla P, Galczynski K, et al. An Open Multicenter Study of Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Urolastic, an Injectable Implant for the Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence: One-Year Observation. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:851823. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/851823.

Pai A, Al-Singary W. Durability, safety and efficacy of polyacrylamide hydrogel (Bulkamid((R))) in the management of stress and mixed urinary incontinence: three year follow up outcomes. Cent European J Urol 2015;68:428–33. https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2015.647.

Toozs-Hobson P, Al-Singary W, Fynes M, et al. Two-year follow-up of an open-label multicenter study of polyacrylamide hydrogel (Bulkamid®) for female stress and stress-predominant mixed incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:1373–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1761-8.

Syan R, Brucker BM. Guideline of guidelines: urinary incontinence. BJU Int 2016;117:20–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13187.

Lineberry N, Berlin JA, Mansi B, et al. Recommendations to improve adverse event reporting in clinical trial publications: a joint pharmaceutical industry/journal editor perspective. BMJ. 2016;355:i5078. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5078.

Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, et al. Trial Reporting in ClinicalTrials.gov - The Final Rule. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1998–2004. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1611785.

Acknowledgments

This report is based on research conducted by the Brown Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract No. 290-2015-00002-I). The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funded the report (PCORI Publication No. 2018-SR-03). The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Aysegul Gozu, MD, MPH, our AHRQ Task Order Officer; Jennifer Croswell, MD, MPH, our PCORI Senior Program Officer; and Kimberly Bailey, MS, our PCORI Program Officer. We would also like to thank and acknowledge the additional research associates and other staff who helped to conduct this systematic review: Valerie Rofeberg, ScM, Georgios Markozannes, MSc, Hannah Kimmel, MPH, Iman Saeed, ScM, Mengyang Di, PhD, Gowri Raman, MBBS, MS, Esther Avendano, MS, Andrew Zullo, PharmD, PhD, Jenni Quiroz, BS, and Anya Wallack, PhD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ or PCORI. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of PCORI, AHRQ, or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balk, E.M., Adam, G.P., Corsi, K. et al. Adverse Events Associated with Nonsurgical Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Women: a Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 1615–1625 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05028-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05028-0