Abstract

Purpose

To quantify the prevalence of anxiety or depression (overall; melanoma-related) among people with high-risk primary melanoma, their related use of mental health services and medications, and factors associated with persistent new-onset symptoms across 4 years post-diagnosis.

Methods

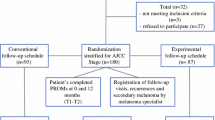

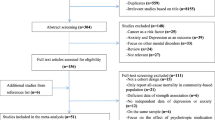

A longitudinal study of 675 patients newly diagnosed with tumor-stage 1b–4b melanoma. Participants completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and answered questions about fear of cancer recurrence, use of medication, and support, serially over 4 years. We identified anxiety and depression trajectories with group-based trajectories models and factors associated with persistent symptoms with logistic regression.

Results

At diagnosis, 93 participants (14%) had melanoma-related anxiety or depression, and 136 (20%) were affected by anxiety and/or depression unrelated to melanoma. After 6 months, no more than 27 (5%) reported melanoma-related anxiety or depression at any time, while the point prevalence of anxiety and depression unrelated to melanoma was unchanged (16–21%) among the disease-free. Of 272 participants reporting clinical symptoms of any cause, 34% were taking medication and/or seeing a psychologist or psychiatrist. Of the participants, 11% (n = 59) had new-onset symptoms that persisted; these participants were more likely aged < 70.

Conclusions

Melanoma-related anxiety or depression quickly resolves in high-risk primary melanoma patients after melanoma excision, while prevalence of anxiety or depression from other sources remains constant among the disease-free. However, one-in-ten develop new anxiety or depression symptoms (one-in-twenty melanoma-related) that persist.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Chronic stress has been linked to melanoma progression. Survivors with anxiety and depression should be treated early to improve patient and, potentially, disease outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ries L, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb D, Howlader N, Horner M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2008.

Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S-J, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199–206.

von Schuckmann L, Hughes M, Ghiasvand R, Malt M, van der Pols J, Beesley V, et al. Risk of melanoma recurrence after diagnosis of a high-risk primary tumor. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(6):688–693.

Cornish D, Holterhues C, van de Poll-Franse LV, Coebergh JW, Nijsten T. A systematic review of health-related quality of life in cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 6):vi51–8.

Rychetnik L, McCaffery K, Morton R, Irwig L. Psychosocial aspects of post-treatment follow-up for stage I/II melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):721–36.

Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Butow PN. Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(12):1415–27.

Beesley VL, Smithers BM, Khosrotehrani K, Khatun M, O'Rourke P, Hughes MC, et al. Supportive care needs, anxiety, depression and quality of life amongst newly diagnosed patients with localised invasive cutaneous melanoma in Queensland, Australia. Psychooncology. 2015;24(7):763–70.

Bell KJL, Mehta Y, Turner RM, Morton RL, Dieng M, Saw R, et al. Fear of new or recurrent melanoma after treatment for localised melanoma. Psychooncology. 2017;26(11):1784–91.

Hall DL, Jimenez RB, Perez GK, Rabin J, Quain K, Yeh GY, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence: a model examination of physical symptoms, emotional distress, and health behavior change. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(9):e787–e797.

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–22.

Colucci R, Moretti S. The role of stress and beta-adrenergic system in melanoma: current knowledge and possible therapeutic options. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(5):1021–9.

Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI, et al. P. for members of the American joint committee on cancer melanoma expert, D. the international melanoma, and P. discovery, Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):472–92.

Health, A.G.D.O. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme A-Z medicine listing. 2019 [cited 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/browse/body-system?depth=1&codes=n#n.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural, regional and remote health: a guide to remoteness classifications. AIHW Canberra: AIHW; 2004.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Brief assessment of adult cancer patients' perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item supportive care needs survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):602–6.

Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:109–38.

Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Methods Res. 2007;35(4):542–71.

Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, Taylor EP. Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40(Pt 4):429–34.

Boyes AW, Girgis A, D'Este CA, Zucca AC, Lecathelinais C, Carey ML. Prevalence and predictors of the short-term trajectory of anxiety and depression in the first year after a cancer diagnosis: a population-based longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(21):2724–9.

Butow P, Price MA, Shaw JM, Turner J, Clayton JM, Grimison P, et al. Clinical pathway for the screening, assessment and management of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: Australian guidelines. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):987–1001.

Whiteford HA, Buckingham WJ, Harris MG, Burgess PM, Pirkis JE, Barendregt JJ, et al. Estimating treatment rates for mental disorders in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(1):80–5.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australia’s Health 2010. 2010, AIHW: Canberra.

Sanzo M, Colucci R, Arunachalam M, Berti S, Moretti S. Stress as a possible mechanism in melanoma progression. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:483493.

Cancer Australia. Principles of Cancer Survivorship. Surry Hills: Cancer Australia; 2017.

Clinical Oncology Society of Australia. Model of survivorship care: critical components of cancer survivorship care in Australia position statement. Sydney: Clinical Oncology Society of Australia; 2016.

Vodermaier A, Millman RD. Accuracy of the hospital anxiety and depression scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(12):1899–908.

McLoone J, Menzies S, Meiser B, Mann GJ, Kasparian NA. Psycho-educational interventions for melanoma survivors: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2013;22(7):1444–56.

Butow P, Sharpe L, Thewes B, Turner J, Gilchrist J, Beith J. Fear of cancer recurrence: a practical guide for clinicians. Oncology (Williston Park). 2018;32(1):32–8.

Harris J, Cornelius V, Ream E, Cheevers K, Armes J. Anxiety after completion of treatment for early-stage breast cancer: a systematic review to identify candidate predictors and evaluate multivariable model development. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(7):2321–33.

Queensland Cancer Registry Cancer Council Queensland, Cancer in Queensland 1982–2013: incidence, Mortality, Survival and Prevalence. 2015.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable contributions of our study staff Angela Carroll and Valerie Logan and clinical collaborators Doctors Mark Zonta (The Townsville Hospital and North Queensland Minimally Invasive Surgery), Gerard Bayley (Princess Alexandra Hospital and Phoenix Plastic Surgery, Greenslopes), Andrew Barbour (Princess Alexandra Hospital and Gastrointestinal & Soft Tissue Clinic, Greenslopes), Christopher Allan (Princess Alexandra Hospital and Mater Public & Private Hospital), Ivan Robertson (Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital), Lee Brown (Coastal Plastic Surgery, Sunshine Coast), Justin D’Arcy (Nambour Hospital & Sunshine Coast Private Hospital Medical Centre), David Weedon (Sullivan Nicolaides Pathology), Dominic Wood (IQ Pathology), and Richard Williamson (Zenith Specialist Pathology). We also thank Dr. Gunter Hartel for his help with formatting the trajectory figures. Finally, we thank all study participants.

Funding

This study and VL Beesley were funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Program (grant nos. 552429, 1073898). K Khosrotehrani was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship (No. 1023371).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 194 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beesley, V.L., Hughes, M.C.B., Smithers, B.M. et al. Anxiety and depression after diagnosis of high-risk primary cutaneous melanoma: a 4-year longitudinal study. J Cancer Surviv 14, 712–719 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00885-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00885-9