Abstract

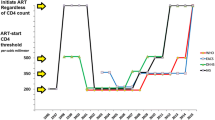

Antiretrovirals perform superbly in combating HIV infection. But when to initiate therapy in asymptomatic, nonpregnant, hepatitis-free, HIV-infected persons is not securely established. Of two completed randomized trials using modern therapy, a Haitian trial demonstrated a benefit to initiating therapy between 200 and 350 CD4 cells/mm3 as compared with less than 200 CD4 cells/mm3 and an international trial demonstrated a benefit to starting at greater than 350 CD4 cells/mm3 as compared with less than 250 CD4 cells/mm3. Many observational cohorts support initiating treatment at less than 350 CD4 cells/mm3. Of these, three large studies supported initiation at less than 350 cells/mm3, less than 450 CD4 cells/mm3, and less than 500 CD4 cells/mm3, respectively, but only the last supported starting at higher counts. Such studies are not probative, given the problem of confounding. No conventional antiretroviral regimen is free of long-term adverse effects, especially over decades of use. All are expensive and require expensive monitoring. When resources are restricted, initiation of antiretrovirals for persons with high CD4 count diverts treatment from more needy persons. Pathophysiological considerations favor universal treatment because antiretrovirals mitigate systemic inflammation, which aggravates atherosclerosis. There are suggestions that HIV hastens the natural decline of cognitive, renal, and pulmonary function as well as bone mineral loss; the mechanism(s) are uncertain, as is the ability of antiretrovirals to counteract the probable acceleration. The four major guideline panels, although all have issued updates in the past year, are not consistent in recommendations for treatment of HIV-infected persons with counts greater than 350 CD4 cells/mm3.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. December 1. 2009; 1–161. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nig.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed November 2010.

European AIDS Clinical Society. Guidelines. Clinical Management and Treatment of HIV Infected Adults in Europe. Available at www.europeanaidsclinicalsociety.org. Accessed November 2010.

Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, et al.: Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection. 2010 Recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA Panel. JAMA 2010;304:321–333.

World Health Organization: Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach, 2010 revision. Available at www.who.int/HIV/pub/guidelines/en. Accessed November 2010.

Study Group on Death Rates at High CD4 Count in Antiretroviral Naive Patients/Lodwick RK, Sabin CA, Porter K, et al.: Death rates in HIV-positive antiretroviral-naive patients with CD4 count greater than 350 cells per μL in Europe and North America: a pooled cohort observational study. Lancet 2010;376:340–345

• Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al.: Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–926. Updated information at www.igh.org/Cochrane/GRADE. Accessed November 2010. The described system will probably become the standard for evaluating the quality of evidence.

Lee GA, Schwartz JM, Patzek S, et al.: The acute effects of HIV protease inhibitors on insulin suppression of glucose production in healthy HIV-negative men. JAIDS 2009;52:246–248.

Tomaka F, Lefebvre E, Sekar V, et al.: Effects of ritonavir-boosted darunavir vs. ritonavir-boosted atazanavir on lipid and glucose parameters in HIV-negative, healthy volunteers. HIV Med 2009;10:318–27. Epub 2009 Feb 5. PMID: 19210693

Lee GA, Mafong DD, Noor MA, et al.: HIV protease inhibitors increase adiponectin levels in HIV-negative men. JAIDS 2004;36:645–7

Cooper CL, Phenix B, Mbisa G, et al.: Antiretroviral therapy influences cellular susceptibility to apoptosis in vivo. Front Biosci 2004;9:338–41. PMID: 14766370

Maagaard A, Kvale D: Long term adverse effects related to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: clinical impact of mitochondrial toxicity. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 41(11–12):808–17, 2009.

Kohler JJ, Lewis W: A brief overview of mechanisms of mitochondrial toxicity from NRTIs. Environ Mol Mutagen 2007;48:166–72. PMID: 16758472

Volberding PA, Lagakos SW, Koch MA, et al.: Zidovudine in asymptomatic HIV infection. A controlled trial in persons with fewer than 500 CD4-positive cells per mm3. N Engl J Med 1990;322:941–9.

Volberding PA, Lagakos SW, Grimes JM, et al.: The duration of zidovudine benefit in persons with asymptomatic HIV. Prolonged evaluation of ACTG 019. JAMA 1994;272:437–42.

Hamilton JD, Hartigan PM, Simberkoff MS, et al.: A controlled trial of early versus late treatment with zidovudine in symptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med 1992;326:484–6

Simberkoff MS, Hartigan PM, Hamilton JD, et al.: Long-term follow-up of symptomatic HIV-infected patients originally randomized to early versus later zidovudine treatment. J AIDS Hum Retrovirol 1996;11:142–50

Concorde Coordinating Committee. Concorde: MRC/ANRS randomized double-blind controlled trail of immediate and deferred zidovudine in symptom-free HIV infection. Lancet 1994;433:871–81.

Joint Concorde and OPAL coordinating committee: Long-term follow-up of randomized trials of immediate versus deferred zidovudine in symptom-free HIV infection. AIDS 1998;12:1259–65

•• Severe P, Jean Juste MA, Ambroise A, et al.: Early versus Standard Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV-Infected Adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 257–265. A study of critical importance in underdeveloped areas regarding the optimal time of initiating antiretroviral therapy.

•• The Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) Study Group/Emery SA, Neuhaus JA, Phillips AN, et al.: Major clinical outcomes in antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve participants and in those not receiving ART at baseline in the SMART study. JID 2008;197:133–144. The only completed randomized study bearing on when to start antiretroviral therapy in developed countries.

Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START). Available at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00867048. Accessed November 2010.

Suissa S: Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:492–499.

Stampfer M, Colditz G: Estrogen replacement therapy and coronary heart disease: a quantitative assessment of the epidemiologic evidence. Prev Med 1991;20:47–63.

Grady D, Rueben SB, Pettiti DB, et al.: Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1016–1037.

Rijpkema AH, van der Sanden AA, Ruijs AH: Effects of postmenopausal estrogen-progesterone therapy on serum lipids and lipoproteins: a review. Maturitas 1990;12:259–285.

Adams MR, Kaplan JR, Manuck SB, et al.: Inhibition of coronary artery atherosclerosis by 17-beta estradiol in ovariectomized monkeys: lack of an effect of added progesterone. Arteriosclerosis. 990;10: 1051–1057.

Mendelsohm M, Karas R: The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1801–11.

Bain C, Willett W, Hennekens CH, et al.: Use of postmenopausal hormones and risk of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1981;64:42–6.

Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators: Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321–33.

•• When to start consortium/Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, et al.: Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1352–63. This is one of the three large observational studies bearing on when to start antiretroviral therapy in developed countries.

•• Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al.: Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(18):1815–1826. This is one of the three large observational studies bearing on when to start antiretroviral therapy in developed countries. It is the only study suggesting initiation should be done at CD4 counts greater than 500 cells/mm 3.

Hernán MA, Robins JM: Letter to the Editor. N Engl J Med 2009;361:822–824.

•• Funk MJ, Fusco JS, Cole SR, et al.: HAART initiation and clinical outcomes: insights from the CASCADE cohort of HIV-1 seroconverters on ‘When to Start’. XVIII International AIDS Conference, Vienna, Austria, July 2010. Abstract THLBB201. This is one of the three large observational studies bearing on when to start antiretroviral therapy in developed countries.

• van Leuven SI, Franssen R, Kastelein JJ, et al.: Systemic inflammation as a risk factor for atherothrombosis. Rheumatilogy 2008;47:3–7. This article is a good review of the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis.

Calmy A, Gayet-Ageron A, Montecucco F, et al.: HIV increases markers of cardiovascular risk: results from a randomized, treatment interruption trial. AIDS. 2009;23(8):929–939.

Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, et al.: Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection. PLoS Med. 2008;5(10):e203.

Fisher SD, Miller TL, Lipshultz SE: Impact of HIV and highly active antiretroviral therapy on leukocyte adhesion molecules, arterial inflammation, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 185(1):1–11, 2006

Baker JV, Duprez D, Rapkin J, et al.: Untreated HIV infection and large and small artery elasticity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(1):25–31.

Torriani FJ, Komarow L, Parker RA, et al.: Endothelial function in human immunodeficiency virus-infected antiretroviral-naive subjects before and after starting potent antiretroviral therapy: The ACTG (AIDS Clinical Trials Group) Study 5152s. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(7):569–576.

• Phillips AN, Carr A, Neuhaus J, et al.: Interruption of antiretroviral therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease in persons with HIV-1 infection: exploratory analyses from the SMART trial. Antiviral Ther 2008;13:177–187. The authors describe an important effort to understand the impact of antiretroviral treatment interruption on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC: Legislating against use of cost-effectiveness information. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1495–149.

Disclosure

Conflicts of interest: service on speakers’ bureaus for Simply Speaking (funded by unrestricted grants from Gilead), Choices (funded by unrestricted grants from Tibotec), Gilead, Tibotec, Merck, and Viiv.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rhame, F.S. When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy. Curr Infect Dis Rep 13, 60–67 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-010-0154-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-010-0154-8