Abstract

To what degree does criminology demonstrate the genuine presence or lack of a paradigm (i.e. theoretical-methodological consensus) to help structure its research enterprise? There are trade-offs to consider when pressing the question, such as a potential drain on efficiency in its allocation of resources, limits on its scientific credibility, and weakened institutional strength resulting from conceptual dissensus. Alternatively, an interdisciplinary field may benefit from insights continually drawn from its various parent disciplines. The present research offers a reply in two parts. The first focus relies on a content analysis of 2,109 peer-reviewed articles published in leading journals from 1951-2008 in providing a positive analysis. There is mixed evidence of methodological agreement and less on the matter of commitment to a specific theory. The second inquiry draws from reactions delivered by 17 leading criminologists on the normative question of whether the field’s a-paradigmatic status helps or harms scientific advance. An analysis of the oral histories indicates an indifference to the criticism of lacking paradigmatic uniformity as a legitimate critique and a vehement defense of porous intellectual boundaries. However, pragmatic considerations such as the potential for a diminishing need to train criminal justice undergraduates and threats to government funding may force the profession to give more consideration to the matter of its scientific bone fides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The matter of merging two independent data gathering efforts required confronting the technical matter of reaching an acceptable threshold of interrater reliability.

Given the differences in sampling between the initial 1951 to 1992 dataset and the extension 1993 to 2008 dataset, the comparison and combination of the two becomes complicated. However, the random sampling procedure used in the extension dataset should allow for an unbiased comparison of patterns and proportions across the two periods. Further aiding comparison were inter-rater reliability checks at several points. Through a series of email exchanges and a personal visit to the University of Minnesota the coding scheme used in the original research a familiarity with the coding scheme was gained. A set of articles were then reverse coded to test those assumptions. These codes were then compared to those in the 1951 to 1992 data. Except for the rate of agreement on the method of analysis (65%), the correspondence was above the modest standard of 70% (Carmines and Zeller 1979).

Inter-rater reliability was then examined for coding within the extension dataset (1993–2008). Following the coding of the random sample of 501 articles from 1993 to 2008, two independent coders were then given instructions on the coding procedure and a random sample of 25 articles to code themselves. The rate of agreement met the minimum standard.

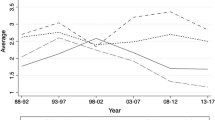

Upon the advice of a reviewer the 26 theory types were collapsed into categories. Figure 2 is sufficient to justify the conclusions drawn in the analysis, illustrating the point of a lack of theoretical uniformity. The observation maintains regardless of how any of the 26 might be shuffled between categories, at least at the margins. The original figure arguably pressed the observation of theoretical dissensus over the top but is available upon request from the author.

The breakdown of the eight declines was as follows. Four dropped correspondence on either the mailed invitation (1) or the email overture (3). Three declined via email responses, generally citing personal reasons. One potential interviewee was approached on the author’s behalf by an interviewee and communicated a preference in declining via that contact. Per an Institutional Review Board stipulation the identities of those who declined to participation must remain confidential.

As with the challenge of operationalizing variables, the attributions made here with categorizing scholars and their scholarship are open to debate. Taking just one of the scholars, John Hagan, the inherent difficulty becomes undeniably apparent. A truncated list of his work includes—race, gender, conflict criminology, international applications of law, imprisonment, white collar crime, labeling perspective, offender decision making street ethnography, among others. It is offered here that a defensible claim to the sample being inclusive of the main thrust of criminological work is present.

Partly because the substantive theory references were split into 26 separate categories, the largest single category in the data was “other”, with 315 mentions over the study period. For purposes of avoiding undue ambiguity in interpretation (see also endnote iii) the code was omitted from Figure 2.

Eight of the theories garnered more than one hundred substantive mentions (listed in descending order: other, differential association, control, rational choice, strain, Miller subcultural, labeling, and illegitimate opportunity) and together comprise nearly two-thirds of the total accumulated (64%, N = 1219). Marxist theory, social disorganization and anomie fall just below the 100 threshold. On the other end of the continuum are six theories (feminist, neutralization, power-control, historical/constructivist, drift/episode, and legitimation of violence) that constitute just over 7 % (N = 135) of the total mentions.

The debate within criminology resembles that over public sociology. The debate is ongoing as to how much involvement the field’s researchers ought to bring to bear in an effort to influence policy outcomes. The dispute is essentially over research ethics and over calibrating the proper balance between objective inquiry and improving quality of life through improving justice policies.

References

Abbott, A. (2001). Chaos of disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Agnew, R. (2005). Why do criminals offend?: A general theory of crime and delinquency. Los Angeles: Roxbury.

Agnew, R. (2011). Toward a unified criminology: Integrating assumptions about crime, people and society. New York: New York University Press.

Akers, R. L. (1992). Linking sociology and its specialties: the case of criminology. Social Forces, 71(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/71.1.1

Allen, M. P. (1990). The ‘quality’ of journals in sociology reconsidered: objective measures of journal influence. The Foot, 18(9), 4–5.

Blumstein, A., & Wallman, J. (Eds.). (2000). The crime drop in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brannigan, A. (1981). The social basis of scientific discoveries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bruinsma, G. (2016). Proliferation of crime causation theories in an era of fragmentation: Reflections on the current state of criminological theory. European Journal of Criminology, 13, 1–18.

Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985642

Cohn, E. G., & Farrington, D. P. (1994). Who are the most-cited scholars in major American criminology and criminal justice journals? Journal of Criminal Justice, 22(6), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(94)90093-0

Cohn, E. G., & Farrington, D. P. (1998). Changes in the most-cited scholars in major American criminology and criminal justice journals between 1986-1990 and 1991-1995. Journal of Criminal Justice, 26(2), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(97)00073-1

Cohn, E. G., & Farrington, D. P. (2007). Changes in scholarly influence in major American criminology and criminal justice journals between 1986 and 2000. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 18(1), 6–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511250601144225

Cohn, E. G., & Farrington, D. P. (2012). Scholarly influence in criminology and criminal justice. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc..

Cohn, E. G., Farrington, D. P., & Wright, R. A. (1998). Evaluating criminology and criminal justice. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Dooley, B. D. (2017). Conjectures, refutations, and (elusive) resolution: an exercise in the sociology of knowledge within criminology. Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice and Criminology, 5, 104–131.

Elliott, D. S., Ageton, S. S., & Canter, R. J. (1979). An integrated theoretical perspective on delinquent behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 16(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242787901600102

Felson, M. (2017). Criminology’s first paradigm. In A. Sidebottom & N. Tilley (Eds.), Handbook of crime prevention and community safety (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Freidrichs, R. W. (1970). A sociology of sociology. New York: Free Press.

Fuchs, S. (1992). The professional quest for truth: A social theory of science and knowledge. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Haskell, T. L. (2000). The emergence of professional social science. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35, 519–530.

Hirschi, T. (1979). Separate and unequal is better. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 16(1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242787901600104

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Laub, J. H. (2006). Edwin H. Sutherland and the Michael-Adler report: searching for the soul of criminology seventy years later. Criminology, 44(2), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00048.x

Messner, S. F., Krohn, M. D., & Liska, A. E. (Eds.). (1989). Theoretical integration in the study of deviance and crime: Problems and prospects. Albany: SUNY Press.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, state, and utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Pfeffer, J. (1993). Barriers to the advance of organizational science: paradigm development as a dependent variable. The Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 599–620.

Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal knowledge. Landon: Routledge.

President's Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice. (1967). The challenge of crime in a free society. US Government Printing Office.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Ritzer, G. (1975). Sociology: A multiple paradigm science. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Savelsberg, J. J., & Flood, S. M. (2004). Criminological knowledge: period and cohort effects in scholarship. Criminology, 42(4), 1009–1041. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2004.tb00543.x

Savelsberg, J. J., & Sampson, R. M. (2002). Mutual engagement: criminology and sociology? Crime, Law and Social Change, 37(2), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014552932605

Savelsberg, J. J., King, R. D., & Cleveland, L. J. (2002). Politicized scholarship? Science on crime and the state. Social Problems, 49(3), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2002.49.3.327

Savelsberg, J. J., Cleveland, L. J., & King, R. D. (2004). Institutional environments and scholarly work: American criminology, 1951-1993. Social Forces, 82(4), 1275–1302. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2004.0093

Shichor, D., O’Brien, R. M., & Decker, D. L. (1981). Prestige of journals in criminology and criminal justice. Criminology, 19(3), 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1981.tb00431.x

Sorensen, J., Snell, C., & Rodriguez, J. J. (2006). An assessment of criminal justice and criminology journal prestige. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 17(2), 297–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511250500336203

Sutherland, E. H. (1947). Principles of criminology (4th ed.). New York: J. B. Lippincott.

Walsh, A., & Ellis, L. (1999). Political ideology and American criminologists’ explanations for criminal behavior. The Criminologist, 24(6), 1, 14, 26‑27.

Wheeldon, J. J., Heidt, J., & Dooley, B. D. (2014). The trouble(s) with unification: Debating assumptions, methods, and expertise in criminology. Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology, 6(2), 111–128.

Whitley, R. (2000). The intellectual and social Organization of the Sciences. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wolfgang, M. E., Figlio, R. M., & Thornberry, T. P. (1978). Evaluating criminology. New York: Elsevier.

Zimring, F. E. (2008). Criminology and its discontents: the American Society of Criminology 2007 Sutherland address. Criminology, 46(2), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00109.x

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Joachim Savelsberg for the generous use of his original data gathered with his research team at the University of Minnesota.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dooley, B.D. Whither Criminology? The Search for a Paradigm Over the Last Half Century. Am Soc 49, 258–279 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-018-9370-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-018-9370-8