Abstract

Existing research points to a democratic advantage in public good provision. Compared to their authoritarian counterparts, democratically elected leaders face more political competition and must please a larger portion of the population to stay in office. This paper provides an impartial reevaluation of the empirical record using the techniques of global sensitivity analysis. Democracy proves to have no systematic association with a range of health and education outcomes, despite an abundance of published empirical and theoretical findings to the contrary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Ross (2006) shows that once missing data problems are accounted for, there is no significant relationship between democracy and infant mortality rates. The expenditures literature has two reported findings that contradict the democratic advantage argument. Mulligan et al. (2004) consider the relationship between regime type and public policy broadly defined, and find that there are not major differences between autocracies and democracies in terms of education spending.

The discussion here follows closely that of Hegre and Sambanis (2006).

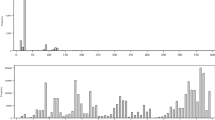

Sala-I-Martin 1997, 179. Technically, the appropriate method for calculating the cumulative distribution function is still under debate. If the estimates appear normally distributed, Sala-I-Martin recommends taking a weighted mean of the estimates and their variances. The idea behind the weighting scheme is to give more weight to estimates from models with better fit, under the assumption that they are more likely to be the “true model.” This weighting is not strictly necessary, and it has recently been criticized on the grounds that goodness-of-fit metrics are generally incomparable across models with different numbers of covariates and observations (Gassebner et al. 2013). For this reason, I will calculate the simple unweighted means for the estimates.

The standard approach is to calculate the mean \( {\overline{\beta}}_{\mathrm{m}} \) and variance \( {\overline{\sigma}}_{\mathrm{m}}^2 \), and then compute the cumulative distribution function using the standard normal approximation. Yet, given that my estimates are unweighted, the simpler method is to just examine the empirical distribution and avoid the normal approximation entirely.

Lake and Baum (2001) actually include GNP per capita, not the logged GDP per capita, but graphical analysis shows that the logged model better approximates a linear relationship. Deacon (2009) also moves back and forth between various income and logged income measures. The replication analysis will employ logged GDP per capita.

To calculate the total number of models, we can employ the combinations formula, n! / (r!(n – r)!), where n is the total number of unique elements, and r is the number of unique elements in the combination. For this analysis, there are 21 possible models that have 2(r) out of the 7(n) concepts.

This measure, which is a sum of five weighted ordinal scores on governance sub-measures (competitiveness of participation, regulation of participation, competitiveness of executive, openness of executive recruitment, constraints on executive), has been strongly criticized as including redundant components, omitting key aspects of democracy, and relying on a “convoluted aggregation rule” that has no theoretical justification. As a consumer of these indices, it is difficult to grasp what a unit change in a country’s Polity score means in terms of reforms on the ground.

In their cross-section analysis, Lake and Baum (2001) examine the two years that have the highest data coverage from each decade (1970, 1975, 1985, 1987, 1990, and 1992). Deacon (2009) presents cross-section findings from data from 1989, Moon and Dixon (1985) aggregate a quality of life index over 1970–1975, and Franco et al. (2004) rely on data from 1998.

References

Avelino G, Brown D, Hunter W. The effects of capital mobility, trade openness, and democracy on social spending in Latin America, 1980-1999. Am J Polit Sci. 2005;49(3):625–41.

Bazzi S, Blattman C. Economic shocks and conflict: The (Absence of?) Evidence from Commodity Prices. Working Paper, 2011.

Besley T, Kudamatsu M. Health and democracy. Am Econ Rev. 2006;96:313–8.

Boone P. Politics and the effectiveness of foreign Aid. Eur Econ Rev. 1996;40:28–329.

Brown D. Reading, writing and regime type: democracy’s impact on primary school enrollment. Pol Res Q. 1999;52(4):681–707.

Brown D, Hunter W. Democracy and social spending in Latin America, 1980-92. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1999;93(4):779–90.

Brown D, Hunter W. Democracy and human capital formation: education spending in Latin America, 1980 to 1997. Comp Pol Stud. 2004;37(7):842–64.

Bueno de Mesquita B, Smith A, Silverson RM, Morrow JD. The logic of political survival. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2003.

Cheibub JA, Gandhi J, Vreeland JR. Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice. 2010;143:67–101.

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Altman D, Bernhard M, Fish S, Hicken A, et al. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: a new approach. Perspect Polit. 2011;9:247–67.

Dafoe A. Statistical critiques of the democratic peace. Am J Polit Sci. 2011;55(2):247–62.

Deacon RT. Public good provision under dictatorship and democracy. Public Choice. 2009;139:241–62.

Deacon RT, Saha S. Public good provision by Dictatorships: A survey. In: Ott AF, Cebula RJ, editors. The Companion in Public Economics: Empirical Public Economics. New York: Edward Elgar Publishing. 2006.

Franco A, Alvarez-Dardet C, Ruiz MT. Effect of democracy on health: ecological study. BMJ. 2004;329:1421–3.

Gassebner M, Lamla MK, Vreeland JR. Extreme bounds of democracy. J Confl Resolut. 2013;57:171–97.

Geddes B, Wright J, Frantz E. New data on autocratic regimes. Working Paper. State College, PA: Penn State University Department of Political Science. 2012.

Gerber A, Malhotra N. Do statistical reporting standards affect what is published? Publication bias in two leading political science journals. Q J Polit Sci. 2008;3:313–26.

Gerber A, Green DP, Nickerson D. Testing for publication bias in political science. Polit Anal. 2001;9:385–92.

Harding R, Stasavage D. What democracy does (and doesn’t do) for basic services: school fees, school inputs, and African elections. J Polit. 2014;76(1):229–45.

Hegre H, Sambanis N. Sensitivity analysis of empirical results on civil war onset. J Confl Resolut. 2006;50:508–35.

Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: a program for missing data. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(7):1–47.

Imai K, King G, Lau O. “ls: Least Squares Regression for Continuous Dependent Variables.” in Kosuke Imai, Gary King, and Olivia Lau, “Zelig: Everyone’s Statistical Software,”. 2015. http://gking.harvard.edu/zelig.

Kaufman RR. Democratic and authoritarian responses to the debt issue: Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Int Organ. 1985;39:473–503.

Kaufman RR, Segura-Ubiergo A. Globalization, domestic politics, and social spending in Latin America: a time-series cross-section analysis, 1973-97. World Polit. 2001;53:553–87.

Kudamatsu M. Has democratization reduced infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa? J Eur Econ Assoc. 2012;10(6):1294–317.

Lake DA, Baum MA. The invisible hand of democracy—political control and the provision of public services. Comp Pol Stud. 2001;34:587–621.

Leamer EE. Sensitivity analyses would help. Am Econ Rev. 1985;75:308–13.

Levine R, Renelt D. A sensitivity analysis of cross-country growth regressions. Am Econ Rev. 1992;82:942–63.

McGuire MC, Olson M. The economics of autocracy and majority rule: the invisible hand and the use of force. J Econ Lit. 1996;34:72–96.

Moon BE, Dixon WJ. Politics, the state, and basic human needs: a cross-national study. Am J Polit Sci. 1985;29(4):661–94.

Mulligan CB, Gil R, Sala-i-Martin X. Do democracies have different public policies than nondemocracies? J Econ Perspect. 2004;18:75–98.

Munck GL, Verkuilen J. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: evaluating alternative indices. Comp Pol Stud. 2002;35(1):5–34.

Przeworski A, Alvarez ME, Cheibub JA, Limongi F. Democracy and development: political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950-1990. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Ross M. Is democracy good for the poor? Am J Polit Sci. 2006;50:860–74.

Sala-I-Martin XX. I just ran two million regressions. Am Econ Rev. 1997;87:178–83.

Stasavage D. Democracy and education spending in Africa. Am J Polit Sci. 2005;49:343–58.

Sturm JE, de Haan J. How Robust is Sala-I-Martin’s Robustness Analysis? Working Paper, 2002.

Wigley S, Akkoyunlu-Wigley A. The impact of regime type on health: does redistribution explain everything? World Polit. 2011;63(4):647–77.

Zweifel TD, Navia P. Democracy, dictatorship, and infant mortality. J Democr. 2000;11(2):99–114.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was written and revised while the author received research support from Yale University, Princeton University, and the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program. Thanks to Allan Dafoe, Thad Dunning, Susan Rose-Ackerman, Ken Scheve, Lily Tsai, and Michael Weaver for their helpful comments on various aspects of the manuscript. Thanks also to the editorial team at SCID and the three anonymous reviewers for their support of the manuscript and constructive feedback. Any remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Replication data available at www.rorytruex.com.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 629 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Truex, R. The Myth of the Democratic Advantage. St Comp Int Dev 52, 261–277 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-015-9192-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-015-9192-4