Abstract

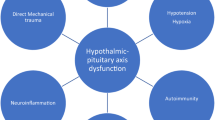

Until recently, the problem of traumatic brain injury in sports and the problem of performance enhancement via hormone replacement have not been seen as related issues. However, recent evidence suggests that these two problems may actually interact in complex and previously underappreciated ways. A body of recent research has shown that traumatic brain injuries (TBI), at all ranges of severity, have a negative effect upon pituitary function, which results in diminished levels of several endogenous hormones, such as growth hormone and gonadotropin. This is a cause for concern for many popular sports that have high rates of concussion, a mild form of TBI. Emerging research suggests that hormone replacement therapy is an effective treatment for TBI-related hormone deficiency. However, many athletic organizations ban or severely limit the use of hormone replacing substances because many athletes seek to use them solely for the purposes of performance enhancement. Nevertheless, in the light of the research linking traumatic brain injury to hypopituitarism, this paper argues that athletic organizations’ policies and attitudes towards hormone replacement therapy should change. We defend two claims. First, because of the connection between TBI and pituitary function, it is likely many more athletes than previously acknowledged suffer from hormone deficiency and thus could benefit from hormone replacement therapy. Second, athletes’ hormone levels should be tested more rigorously and frequently with an emphasis on monitoring TBI and TBI-related issues, rather than simply monitoring policy violations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For instance, in the British Journal of Sports Medicine’s “Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sports” there is no mention of this issue, nor is there any mention throughout the entire issue, despite the fact that it is dedicated to concussion in sports [51].

As of February 27, 2014 the Nevada State Athletic Commission no longer considers applications for TUEs for TRT [52].

Nevertheless, in a recent prospective study Kelly et al. [44] examined the relationship between hormone dysfunction, concussion, and quality of life in retired NFL players. Surprisingly, they did not find that the amount of NFL games played and the number of reported concussions correlated with an increase in hormone dysfunction. Although the exact cause of hormone dysfunction in these players is unknown, the results suggest that hormone dysfunction contributes to poor quality of life. It should be noted, however that there were several notable limitations in this study. For instance, the sample size of NFL players with hormone dysfunction was significantly lower than the sampe size of NFL players without hormone dysfunction. Additionally, it is notoriously difficult to monitor the concussion history and steroid use history in athletes [44].

It should be noted that women can suffer with TBI-related hypogonadism [11]. However, in most studies it is either the case that estradiol, rather than testosterone, concentration is used to test for the occurrence of hypogonadism in women [1–3], or that sex steroids are only tested in the men involved in the study [5, 33]. To our knowledge, there is no data linking TBI and low testosterone levels in women, and so TBI-related hypogonadism in women may specifically involve hypoestrogenism. Because of this, and because of the fact that hypogonadism in women is typically treated with a combination of estrogen and progesterone [57], prescribing HRT for female athletes suffering from TBI-related hypogonadism may not run into issues concerning performance enhancement, since estrogen and progesterone are not generally used for this purpose.

It should be noted that it is unlikely that the ARP takes each reason to be independently sufficient for the ban. Rather, it seems that they hold that each reason is necessary to conclude for the ban.

There are strong reasons to question the legitimacy of a distinction between natural and unnatural treatment. It is notoriously difficult to draw a clear distinction between these terms and even if such a distinction could be made, it is unclear that natural things are always good and unnatural things are always bad. [48]. However, for the purposes of this paper, we shall assume that such a distinction is clear and appropriate.

(C) is not a common reason for needing TRT because the majority of contact sport athletes tend to be younger, and age-related hypogonadism usually does not begin until mid-forties in men [43]. Thus, if a younger athlete is suffering with low testosterone it is unlikely due to age-related causes. Additionally, it should be noted that the prevalence of age-related low testosterone has likely been overstated by the media [58]. Some researchers attribute the cause of decreased testosterone levels in aging men to other causes, such as illness and weight gain, and do not think that age itself is a significant factor [59, 60].

Additionally, it should be noted that in many contact sports, including boxing and MMA, athletes are allowed to treat tendon injury with steroid or analgesic injections—even though these treatments can be performance enhancing. This raises further questions about why the ARP is specifically prohibiting HRT and not these other treatments as well.

Note that one might argue that if it could be shown that the probable cause of Tom’s low testosterone levels was steroids, then it would be justifiable to deny him a TUE for TRT. Although we do think there are ways to counter these arguments so that it ends up being justifiable for Tom to receive a TUE regardless of his past history, we will not discuss this issue here because it concerns the legitimacy of performance enhancement in sports more generally, rather than the legitimacy of using performance enhancing drugs from treating TBI-related conditions.

References

Agha, A., B. Rogers, M. Sherlock, P. O’Kelly, W. Tormey, J. Phillips, et al. 2004. Anterior pituitary dysfunction in survivors of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 89: 4929–4936.

Aimaretti, G., M.R. Ambrosio, C. Di Somma, A. Fusco, S. Cannavo, et al. 2004. Traumatic brain injury and subarachnoid haemorrhage are conditions at high risk for hypopituitarism: Screening study at 3 months after the brain injury. Clinical Endocrinology 61: 320–326.

Bondanelli, M., L. De Marinis, M.R. Ambrosio, M. Monesi, D. Valle, M.C. Zatelli, et al. 2004. Occurrence of pituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 21: 685–696.

Herrmann, B.L., J. Rehder, S. Kahlke, H. Wiedemayer, A. Doerfler, W. Ischebeck, et al. 2006. Hypopituitarism following severe traumatic brain injury. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes 114: 316–321.

Lieberman, S.A., A.L. Oberoi, C.R. Gilkison, B.E. Masel, and R.J. Urban. 2001. Prevalence of neuroendocrine dysfunction in patients recovering from traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 86: 2752–2756.

Popovic, V., S. Pekic, D. Pavlovic, N. Maric, M. Jasovic-Gasic, B. Djurovic, et al. 2004. Hypopituitarism as a consequence of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and its possible relation with cognitive disabilities and mental distress. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 27: 1048–1054.

Schneider, H.J., M. Schneider, B. Saller, S. Petersenn, M. Uhr, B. Husemann, et al. 2006. Prevalence of anterior pituitary insufficiency 3 and 12 months after traumatic brain injury. European Journal of Endocrinology 154: 259–265.

Tanriverdi, F., H. Senyurek, K. Unluhizarci, A. Selcuklu, F.F. Casanueva, and F. Kelestimur. 2006. High risk of hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury: a prospective investigation of anterior pituitary function in the acute phase and 12 months after trauma. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 91: 2105–2111.

High Jr., W.M., M. Briones-Galang, J.A. Clark, C. Gilkison, K.A. Mossberg, D.J. Zgaljardic, B.E. Masel, and R.J. Urban. 2010. Effect of growth hormone replacement therapy on cognition after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 27: 1565–1575.

Verhelst, J., and R. Abs. 2009. Cardiovascular risk factors in hypopituitary GH-deficient adults. European Journal of Endocrinology 161: S41–S49.

Agha, A., and C.J. Thompson. 2006. High risk of hypogonadism after traumatic brain injury: clinical implications. Pituitary 8: 245–249.

Tanriverdi, F., K. Unluhizarci, Z. Karaca, F.F. Casanueva, and F. Kelestimur. 2010. Hypopituitarism due to sports related head trauma and the effects of growth hormone replacement in retired amateur boxers. Pituitary 13: 111–4.

Jordan B. D. 1991. Sports injuries. Proceedings of the mild brain injury in sports summit Dallas, National athletic trainers’ association research & education foundation, 43–45.

Kelly, J.P., J.S. Nichols, C.M. Filley, K.O. Lillehei, D. Rubinstein, and B.K. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters. 1991. Concussion in sports: guidelines for the prevention of catastrophic outcome. Journal of the American Medical Association 266: 2867–2869.

Association of Ringside Physicians Releases Consensus Statement on Therapeutic Use Exemptions for Testosterone Replacement Therapy. 2014. http://www.associationofringsidephysicians.org/testosterone.pdf.Accessed 17 February 2014.

Kraus, J., and D. McArthur. 2000. Epidemiology of brain injury. In Head injury, 4th ed., ed. P. Cooper and J. Golfinos, 1–26. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers.

Sundaram, N.K., E.B. Geer, and B.D. Greenwald. 2013. The impact of traumatic brain injury on pituitary function. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America 42: 565–83.

Dubourg, J., and M. Messerer. 2011. Sports-related chronic repetitive head trauma as a cause of pituitary dysfunction. Journal of Neurosurgery 31: E2.

Schneider, H.J., I. Kreitschmann-Andermahr, E. Ghigo, G.K. Stalla, and A. Agha. 2007. Hypothalamopituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review. Journal of the American Marketing Association 298: 1429–38.

Bondanelli, M., M.R. Ambrosio, M.C. Zatelli, L. De Marinis, and E.C. degli Uberti. 2005. Hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury. European Journal of Endocrinology 152: 679–691.

Aimaretti, G., M.R. Ambrosio, C. Di Somma, M. Gasperi, S. Cannavò, C. Scaroni, et al. 2005. Residual pituitary function after brain injury-induced hypopituitarism: a prospective 12-month study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 90: 6085–6092.

Tanriverdi, F., H. Ulutabanca, K. Unluhizarci, A. Selcuklu, F.F. Casanueva, and F. Kelestimur. 2008. Three years prospective investigation of anterior pituitary function after traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Clinical Endocrinology 68: 573–579.

Tanriverdi, F., A. De Bellis, H. Ulutabanca, A. Bizzarro, A.A. Sinisi, et al. 2013. A five year prospective investigation of anterior pituitary function after traumatic brain injury: is hypopituitarism long-term after head trauma associated with autoimmunity? Journal of Neurotrauma 30: 1426–33.

Agha, A., B. Rogers, M. Sherlock, W. Tormey, J. Phillips, and C.J. Thompson. 2004. Anterior pituitary dysfunction in survivors of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 89: 4929–4936.

Kelestimur, F., F. Tanriverdi, H. Atmaca, K. Unluhizarci, A. Selcuklu, and F.F. Casanueva. 2004. Boxing as a sport activity associated with isolated GH deficiency. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 27: RC28–RC32.

Tanriverdi, F., A. De Bellis, M. Battaglia, G. Bellastella, A. Bizzarro, A.A. Sinisi, et al. 2010. Investigation of antihypothalamus and antipituitary antibodies in amateur boxers: is chronic repetitive head trauma-induced pituitary dysfunction associated with autoimmunity? European Journal of Endocrinology 162: 861–867.

Tanriverdi, F., K. Unluhizarci, B. Coksevim, A. Selcuklu, F.F. Casanueva, and F. Kelestimur. 2007. Kickboxing sport as a new cause of traumatic brain injury-mediated hypopituitarism. Clinical Endocrinology 66: 360–366.

Ives, J.C., M. Alderman, and S.E. Stred. 2007. Hypopituitarism after multiple concussions: a retrospective case study in an adolescent male. Journal of Athletic Training 42: 431–439.

Foley, C.M., and D.H. Wang. 2012. Central diabetes insipidus following a sports-related concussion: a case report. Sports Health 4: 139–41.

Su, D.H., Y.C. Chang, and C.C. Chang. 2005. Post-traumatic anterior and posterior pituitary dysfunction. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 104: 463–467.

Wilkinson, C.W., K.F. Pagulayan, E.C. Petrie, C.L. Mayer, E.A. Colasurdo, et al. 2012. High prevalence of chronic pituitary and target-organ hormone abnormalities after blast-related mild traumatic brain injury. Frontiers in Neurology 3: 11.

Moreau, O., E. Yollin, E. Merlen, W. Daveluy, and M. Rousseaux. 2012. Lasting pituitary deficiency after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 29: 81–89.

Agha, A., B. Rogers, D. Mylotte, F. Taleb, W. Tormey, J. Phillips, and C.J. Thompson. 2004. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in the acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Clinical Endocrinology 60: 584–591.

Aimaretti, G., M.R. Ambrosio, S. Benvenga, G. Borretta, L. De Marinis, et al. 2004. Hypopituitarism and growth hormone deficiency (GHD) after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Growth Hormone & IGF Research 14: 114–117.

Kelly, D.F., I.T. Gonzalo, P. Cohan, N. Berman, R. Swerdloff, and C. Wang. 2000. Hypopituitarism following traumatic brain injury and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a preliminary report. Journal of Neurosurgery 93: 743–752.

Falleti, M.G., P. Maruff, P. Burman, and A. Harris. 2006. The effects of growth hormone (GH) deficiency and GH replacement on cognitive performance in adults: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31: 681–691.

Maric, N.P., M. Doknic, D. Pavlovic, S. Pekic, M. Stojanovic, M. Jasovic-Gasic, and V. Popovic. 2010. Psychiatric and neuropsychological changes in growth hormone-deficient patients after traumatic brain injury in response to growth hormone therapy. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 33: 770–775.

Svensson, J., A. Mattsson, T. Rosén, L. Wirén, G. Johannsson, B.-Å. Bengtsson, and Häggström M. Koltowska. 2004. Three-years of growth hormone (GH) replacement therapy in GH-deficient adults: effects on quality of life, patient-reported outcomes and healthcare consumption. Growth Hormone & IGF Research 14: 207–215.

Reimunde, P., A. Quintana, B. Castanon, N. Casteleiro, Z. Vilarnovo, A. Otero, A. Devesa, X.L. Otero-Cepeda, and J. Devesa. 2011. Effects of growth hormone (GH) replacement and cognitive rehabilitation in patients with cognitive disorders after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 25: 65–73.

Fraietta, R., D.S. Zylberstejn, and S.C. Esteves. 2013. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism revisited. Clinics (São Paulo, Brazil) 68: 81–8.

Traish, A.M., M.M. Miner, A. Morgentaler, and M. Zitzmann. 2011. Testosterone deficiency. The American Journal of Medicine 124: 578–587.

Tomlinson J. W., Holden N., Hills R. K., Wheatley K., Clayton R. N., Bates A. S., Sheppard M. C., Stewart P. M., and the West Midland Prospective Hypopituitary Study Group. 2001. Association between premature mortality and hypopituitarism. Lancet 357: 425–431.

Faiman, C. 2012. Endocrinology: Male Hypogonadism. Cleveland Clinc. http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/endocrinology/male-hypogonadism/. Accessed 23 February 2014.

Kelly, D.F., et al. 2014. Prevalence of pituitary hormone dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, and impaired quality of life in retired professional football players: a prospective study. Journal of Neurotrauma. doi:10.1089/neu.2013.3212.

Kumar, P., N. Kumar, D. Thakur, and A. Patidar. 2010. Male hypogonadism. Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology and Research 1: 297–301.

Brown, W.M. 1980. Drugs, ethics, and sport. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 7: 15–23.

Lavin, M. 1987. Sports and drugs: are the current bans justified? Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 14: 35–43.

Kamm, F.M. 2005. Is there a problem with enhancement? The American Journal of Bioethics 5: 5–14.

Pirola, I., C. Cappelli, A. Delbarba, T. Scalvini, B. Agosti, D. Assanelli, et al. 2010. Anabolic steroids purchased on the internet as a cause of prolonged hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Fertility and Sterility 94(2331): e1–2331.e3.

Boregowda, K., L. Joels, J.W. Stephens, and D.E. Price. 2011. Persistent primary hypogonadism associated with anabolic steroid abuse. Fertility and Sterility 96: e7–8.

McCrory, P., H. Willem, M.A. Meeuwisse, B. Cantu, J. Dvořák, R.J. Echemendia, L. Engebretsen, et al. 2013. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th international conference on concussion in sport held in Zurich, November 2012. British Journal of Sports Medicine 47: 250–258.

Nevada State Athletic Commission. 2014. http://boxing.nv.gov/faq/sections/Drugs_Medications/. Accessed 29 May 2014.

Bulow, B., L. Hagmar, P. Orbaek, K. Osterberg, and E.M. Erfurth. 2002. High incidence of mental disorders, reduced mental well-being and cognitive function in hypopituitary women with GH deficiency treated for pituitary disease. Clinical Endocrinology 56: 183–193.

Almqvist, O., M. Thorén, M. Sääf, and O. Eriksson. 1986. Effects of growth hormone substitution on mental performance in adults with growth hormone deficiency: a pilot study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 11: 347–3.

Golgeli, A., F. Tanriverdi, C. Suer, C. Gokce, C. Ozesmi, F. Bayram, and F. Kelestimur. 2004. Utility of P300 auditory event related potential latency in detecting cognitive dysfunction in growth hormone (GH) deficient patients with sheehan’s syndrome and effects of GH replacement therapy. European Journal of Endocrinology 150: 153–159.

Oertel, H., H.J. Schneider, G.K. Stalla, F. Holsboer, and J. Zihl. 2004. The effect of growth hormone substitution on cognitive performance in adult patients with hypopituitarism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 839–850.

Gooren, L.J.G., and M.C.M. Bunck. 2004. Androgen replacement therapy. Drugs 64 (17): 1861–1891.

Singer, N. 2013, November 24. Selling that new-man feeling. New York Times, p. BU1 http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/24/business/selling-that-new-man-feeling.html?_r=1&. Accessed 17 June 2014.

Sartorius, G., S. Spasevska, A. Idan, L. Turner, E. Forbes, A. Zamojska, C.A. Allan, L.P. Ly, A.J. Conway, R.I. McLachlan, and D.J. Handelsman. 2012. Serum testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and estradiol concentrations in older men self-reporting very good health: the healthy man study. Clinical Endocrinology 77: 755–763. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04432.x.

Grant, Janet F., Sean A. Martin, Anne W. Taylor, David H. Wilson, Andre Araujo, Robert JT Adams, Alicia Jenkins et al. 2013. Cohort profile: the men androgen inflammation lifestyle environment and stress (MAILES) study. International Journal of Epidemiology: dyt064.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their help with this paper: Nathan Adams, Jason Gardner, Tyler Paytas, Gualtiero Piccinini, Shane Reuter, and Christopher Heath Wellman.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors contributed equally to this paper. Thus, the names are merely in reverse alphabetical order.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malanowski, S., Baima, N. On Treating Athletes with Banned Substances: The Relationship Between Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, Hypopituitarism, and Hormone Replacement Therapy. Neuroethics 8, 27–38 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-014-9215-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-014-9215-2