Abstract

Purpose

Failed conversion of epidural labor analgesia (ELA) to epidural surgical anesthesia (ESA) for intrapartum Cesarean delivery (CD) has been observed in clinical practice. However, spinal anesthesia (SA) in parturients experiencing failed conversion of ELA to ESA has been associated with an increased incidence of serious side effects. In this retrospective cohort analysis, we examined our routine clinical practice of removing the in situ epidural, rather than attempting to convert to ESA, prior to administering SA for intrapartum CD.

Methods

Hemodynamic data, frequencies of either high or total spinal block, and maternal and neonatal outcome data were gathered from the anesthesia records of all parturients at the Amphia Hospital, undergoing intrapartum CD between January 1, 2001 and May 1, 2005.

Results

Complete data were available for 693 patients (97.6%) of the 710 medical records that were identified. Of the 693 patients, 508 (73.3%) had no ELA and received SA, 128 patients (18.5%) received SA following epidural anesthesia for labor, 19 (2.7%) underwent conversion of ELA to ESA, and 38 (5.5%) received general anesthesia. When comparing both SA groups, no clinically relevant differences were observed regarding the incidence of total spinal block (0% in both groups) or high spinal block (0.2 vs 0.8%, P = 0.36). The number of hypotensive episodes, the total amount of ephedrine administered, and the Apgar scores recorded at 5 and 10 min were similar amongst groups.

Conclusions

The incidence of serious side effects associated with SA for intrapartum CD following ELA is low and not different compared to SA only.

Résumé

Objectif

Dans la pratique clinique, l’échec du passage d’une analgésie péridurale pour le travail obstétrical à une anesthésie péridurale chirurgicale pour un accouchement par césarienne a été observé. Cependant, la rachianesthésie réalisée chez les parturientes chez qui la conversion de la péridurale avait échoué a été associée à une incidence accrue d’effets secondaires graves. Dans cette analyse de cohorte rétrospective, nous avons examiné notre pratique clinique habituelle, qui consistait à retirer le cathéter péridural avant de réaliser une rachianesthésie pour un accouchement par césarienne, plutôt que de tenter une conversion de la péridurale.

Méthode

Les données hémodynamiques, les fréquences de réalisation de blocs rachidiens élevés ou totaux, et les données de suivi de la mère et du nouveau-né ont été recueillies à partir des dossiers anesthésiques de toutes les parturientes ayant subi un accouchement par césarienne après un travail entre le 1er janvier 2001 et le 1er mai 2005 à l’hôpital Amphia.

Résultats

Les données étaient disponibles dans leur intégralité pour 693 patientes (97,6 %) sur les 710 dossiers médicaux identifiés. Sur les 693 patientes, 508 (73,3 %) n’ont pas eu de péridurale pour le travail et ont eu une rachianesthésie, 128 (18,5 %) ont reçu une rachianesthésie après une anesthésie péridurale pour le travail, 19 (2,7 %) ont subi une conversion de la péridurale, et 38 (5,5 %) ont reçu une anesthésie générale. Si l’on compare les deux groupes rachianesthésie, aucune différence pertinente sur le plan clinique n’a été observée quant à l’incidence d’un bloc rachidien total (0 % dans les deux groupes) ou d’un bloc rachidien élevé (0,2 vs 0,8 %, P = 0,36). Le nombre d’épisodes d’hypotension, la quantité totale d’éphédrine administrée et les scores Apgar enregistrés à 5 et 10 min étaient comparables dans les différents groupes.

Conclusion

L’incidence d’effets secondaires graves avec la rachianesthésie pour un accouchement par césarienne après une péridurale pour le travail est faible et ne diffère pas de l’incidence avec rachianesthésie seulement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Although it has been generally agreed that spinal anesthesia (SA) is the preferred anesthetic technique for Cesarean delivery (CD), epidural anesthesia is advised when an epidural catheter is already in place.1 However, the efficacy of epidural anesthesia has been reported as inferior to that of SA in both elective and emergency situations.1,2 Although it has been associated with a high incidence of deleterious effects, such as high-level or total spinal block, respiratory insufficiency, and hypotension3–8 an increased use of SA for intrapartum CD following epidural labor analgesia (ELA) has been observed.2,9

In our practice, patients who present for intrapartum CD, after receiving an epidural catheter for pain relief during labor, routinely receive SA after the epidural catheter is removed without an attempt to administer local anesthetic to convert ELA to epidural surgical anesthesia (ESA). To assess the efficacy and safety of this technique, we conducted a retrospective cohort analysis to compare 128 cases of SA for intrapartum CD in parturients with ELA with a control group of 508 patients who received only SA for intrapartum CD.

Methods

Following institutional ethics committee approval, we undertook a retrospective cohort analysis of anesthesia records that dated from January 1, 2001 to May 1, 2005 and concerned women who underwent intrapartum CD at the Amphia Hospital, The Netherlands, after failed trial of labor.

The parturients were divided into four groups according to the anesthetic techniques used. The first group (SA) received only SA. The second group (ELA/SA) received ELA followed by removal of the epidural catheter and SA. A third group (ELA/ESA) received ELA, which was converted to ESA, and a fourth group (GA) received general anesthesia. If a patient was given general anesthesia after an insufficient spinal or epidural block, the patient was included in the group of the first anesthetic technique, and the conversion to general anesthesia was recorded.

Data regarding demographics were recorded, as well as data concerning epidural analgesia, fluid administration, incidence of total spinal block (defined as documented impaired breathing and loss of consciousness requiring tracheal intubation), incidence of high spinal block (defined as the patient complaining of impaired breathing not requiring intubation), number of 5 min periods with systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg, total dose of ephedrine, total dose of atropine, conversion to general anesthesia, Apgar scores, and birth weight. Summary statistics for all continuous variables are presented as medians (interquartile range). Categorical data are summarized as frequencies and percentages. Differences in baseline characteristics were not statistically compared. Since the focus of our investigation concerned comparison of outcome between the SA and ELA/ESA groups, clinical outcome data were statistically compared between these two groups alone using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Conduct of epidural labor analgesia

In our institution, epidural analgesia is started at the request of the mother, usually at a cervical dilatation of 1–4 cm. During the study period, after inserting a Perifix® epidural catheter (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) 3–5 cm in the epidural space at the L2-3 or L3-4 intervertebral space, 8–10 mL ropivacaine 1.6 mg · mL−1 with sufentanil 1 μg · mL−1 was injected. When pain was reduced to an acceptable level, a continuous epidural infusion of ropivacaine 1.3 mg · mL−1 with sufentanil 0.8 μg · mL−1 was started at a rate of 8 mL · hr−1. In case of inadequate analgesia, the infusion rate was increased in increments of 2 mL · hr−1 up to a maximum of 12 mL · hr−1. No top-up doses were given. According to local obstetric practice, ELA was discontinued when full dilation was reached.

Conduct of spinal anesthesia for intrapartum Cesarean delivery

No epidural top-up doses were given prior to SA. All anesthesiologists used 25G or 27G Pencan® pencil-point spinal needles (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) at the L2-3 or L3-4 intervertebral space. One and a half to 3 mL of plain or hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5%, with or without sufentanil 1.5–3.0 μg, was used as local anesthetic, according to the preference of the attending anesthesiologist. The spinal medication was recorded from the anesthesia records. A 500 mL intravenous infusion of colloid was started prior to the spinal anesthetic, and ephedrine in 5–10 mg increments was given intravenously when systolic blood pressure was lower than 100 mmHg.

Results

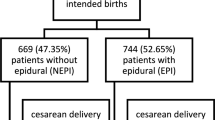

Of the 710 anesthesia records of parturients undergoing intrapartum CD that were identified, 693 (97.6%) included a complete set of data. Five hundred eight (73.3%) of these parturients had no ELA and underwent SA, 128 (18.5%) received SA following the discontinuation of functioning ELA, 19 (2.7%) underwent conversion of ELA to ESA, and 38 (5.5%) had general anesthesia. One patient in the ELA/ESA group required conversion of GA because of inadequate block. Seventeen medical records (12 in the SA group, two in the ELA/SA group, and three in the other groups) could not be retrieved or did not contain sufficient data.

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. Baseline data and epidural and SA data are presented in Table 2. Patients’ height and weight and extent of spinal and epidural block were not sufficiently recorded in the medical charts to be analyzed. Outcome data are presented in Table 3. No statistically significant differences were found regarding the incidence of the following criteria: total or high levels of spinal block, number of 5 min intervals with systolic blood pressure <100 mm, total amount of ephedrine administered, overall conversion to GA, conversion to GA because of inadequate anesthesia, and Apgar scores (Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test or Fisher’s exact test).

In the ELA/SA group, ELA was continued in 35 women (27.3%) until arrival at the operating room, discontinued in less than 20 min in 22 patients (17.2%), and discontinued between 20 and 60 min in 66 women (51.6%). In five women (3.9%), the interval between discontinuation of ELA and SA was unknown.

General anesthesia was used as the first-choice anesthetic in the following cases: severe fetal distress in 15 women (39.5%), at the request of the mother in seven women (18.4%), and in one case each (2.6%) of spina bifida, language barrier, thrombocytopenia, and placental abruption. The reason for GA was not recorded in 12 cases (31.6%). There were no failed tracheal intubations.

Conversion of SA to GA in the SA group was indicated because of insufficient anesthesia in six women (1.2%), failure to locate the subarachnoid space in four women (0.8%), and bleeding from the ligamentum latum in two women (0.4%). The reason for conversion was unknown in one patient (0.2%) in this group. Conversion of SA to GA in the ELA/SA group was indicated because of insufficient anesthesia in two women (1.6%), failure to locate the subarachnoid space in one woman (0.8%), and uterine rupture in one woman (0.8%). The reason for conversion was unknown in one patient (0.8%) in this group.

Discussion

The main purpose of presenting this cohort analysis of 128 patients was to add to the current literature on SA for intrapartum CD following ELA. We believe that SA for intrapartum CD in patients who have had ELA suffers a poorly justified reputation of frequent high or total spinal block, and that SA merits consideration, in particular, when there are doubts about the reliability of an epidural catheter already in place. Our series differs from earlier case series2,9 in that we have compared the results with a group who received only SA for intrapartum CD during the same time period.

In our study cohort, SA proved to be effective for intrapartum CD, with an overall need to convert to GA occurring in 2.6–3.9% of cases and a conversion rate to GA because of inadequate anesthesia after successful intrathecal injection in 1.2–1.6% of cases. These failure rates of patients receiving SA are comparable with the failure rate of 2.7% reported in 2314 spinal anesthetics for CD as part of a retrospective analysis.10 Also, these rates comply with the conversion rate of ≤3% recommended in the Royal College of Anesthetists’ audit criteria for best practice.11 We found no difference in the incidence of total or high spinal block or in the amount of ephedrine used and incidence of hypotension. Since this is a retrospective analysis and no strict definitions were used during the study period, underreporting may have occurred in both groups. Also, the fact that block heights were not recorded is one of the major weaknesses of our study. However, we are confident that total spinal block requiring tracheal intubation would have been obvious on the anesthetic record by the use of general anesthetics and muscle relaxants. Given the low incidence of severe side effects (e.g., total spinal block), statistical power is limited.

Given the relatively small groups, we did not statistically compare demographic and baseline data. However, we believe that there are no clinically relevant differences. Only one patient in the ELA/ESA group required GA. However, this group was very small, and the patients in this group may have been selected because of lack of any doubt that ELA was sufficient.

At present, conversion of ELA to ESA for intrapartum CD is considered standard practice. Indeed, a recent Cochrane review based on ten trials concluded that there are no differences in the efficacy of ESA vs SA for CD.12 However, in recent studies, inadequate surgical anesthesia after conversion of ELA to ESA for CD necessitated conversion to GA in 2.5–20% of cases and provision of additional analgesia was even more frequent.13–19 Only one underpowered study reported a conversion rate to GA of 0%.20 In fact, inadequate ESA has led to litigation against anesthesiologists.9 Breakthrough pain during labor and the number of top-ups required to maintain ELA were demonstrated as being important factors in predicting failure of the same epidural catheter for anesthesia during intrapartum CD.13,15,19,21 Furthermore, although likely seldom, extension of epidural blockade for intrapartum CD may result in high blocks and intravascular injections with seizures or cardiac arrest.22 This likelihood has prompted us to choose SA for intrapartum CD, regardless whether the patient received ELA. However, while we did not find an increased incidence of complications, our results indicate that SA following epidural analgesia also carries a risk of failure. Furthermore, performing another neuraxial technique potentially introduces concomitant risks, e.g., neural injury or infection.

Spinal anesthesia for elective CD is supported by several studies that report higher success rates than with epidural anesthesia.1,10 However, in anecdotal reports on SA following failed epidural anesthesia for intrapartum CD, concerns were raised that this technique may result in a higher incidence of high or total spinal block.3–8 Also, a series of three patients with high spinal blocks after continuous ELA without top-up doses (comparable with our SA group) has been reported.23 In contrast, SA has been safely used for intrapartum CD in patients with failed epidural anesthesia after epidural infusions with or without top-up dosing,2,24 and in patients selected because of inadequate labor epidural analgesia.25 Leakage of local anesthetic from the epidural to the subarachnoid space and cephalad displacement of local anesthetic in the cerebrospinal fluid by epidurally injected fluid have both been implicated as causes for higher spinal block. This may explain the difference between our patients, who received continuous ELA with no top-up doses prior to SA, and those of other authors who studied patients who received considerable top-up volumes of epidural local anesthetics, which failed to produce surgical anesthesia. Indeed, compared with administering SA in the presence of an epidural that was not topped-up, high spinal block occurs more frequently when SA is administered after an unsuccessful epidural top-up.2

Our obstetric and obstetric anesthetic practices may differ from North American practice in several ways. First, ELA is not as commonly applied in the Netherlands compared with other countries. The ELA rate during the study period was approximately 25%. Second, there were no epidural top-ups during the course of ELA. Third, at the request of our obstetricians, ELA is routinely discontinued when full dilation is reached. These differences should be taken into account when interpreting our data.

We are aware that our data suffer from the general limitations of retrospective analyses and lack statistical power. However, with the incidence of high or total spinal block found in our study, groups of 3500 patients would be required to detect a statistically significant difference in high or total spinal blocks in a randomized clinical trial. This retrospective review does, however, indicate that SA provides effective anesthesia for intrapartum CD with no documented adverse outcomes, whether or not ELA was previously in situ.

In conclusion, in this retrospective cohort analysis, we reviewed our practice to perform SA as an alternative to epidural top-up in women who have received ELA and present for intrapartum CD. We did not find an increased incidence of serious side effects with this technique compared with a group of women receiving only SA. However, since failure to provide adequate anesthesia does occur and an additional neuraxial puncture is required, it remains to be demonstrated whether this technique is superior to epidural top-up.

References

Levy DM. Emergency caesarian section: best practice. Anaesthesia 2006; 61: 786–91.

Kinsella SM. A prospective audit of regional anaesthesia failure in 5080 caesarean sections. Anaesthesia 2008; 63: 822–32.

Stone PA, Thorburn J, Lamb KS. Complications of spinal anaesthesia following extradural block for caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 1989; 62: 335–7.

Beck GN, Griffiths AG. Failed extradural anaesthesia for caesarean section. Complication of subsequent spinal block. Anaesthesia 1992; 47: 690–2.

Dell RG, Orlikowski CE. Unexpectedly high spinal anaesthesia following failed extradural anaesthesia for caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1993; 48: 641.

Mets B, Broccoli E, Brown AR. Is spinal anesthesia after failed epidural anesthesia contraindicated for Cesarean section? Anesth Analg 1993; 77: 629–31.

Goldstein MM, Dewan DM. Spinal anesthesia after failed epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1994; 79: 1206–7.

Furst SR, Reisner LS. Risk of high spinal anesthesia following failed epidural block for Cesarean delivery. J Clin Anesth 1995; 7: 71–4.

Dresner M, Brennan A, Freeman J. Six year audit of high regional blocks in obstetric anaesthesia. Int J Obstet Anesth 2003; 12: S10.

Pan PH, Bogard TD, Owen MD. Incidence and characteristics of failures in obstetric neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia; a retrospective analysis of 19, 259 deliveries. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004; 13: 227–33.

Russell IF. Technique of anaesthesia for caesarean section, Chapter 8.8. In: Kinsella M, editor. Raising the Standards: a Compendium of Audit Recipes. Royal College of Anaesthetists; 2006.

Ng KW, Parsons J, Cyna AM, Middleton P. Spinal versus epidural anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews; Issue 2; 2004. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003765.pub2.

Lee S, Lew E, Lim Y, Sia AT. Failure of augmentation of labor epidural analgesia for intrapartum Cesarean delivery: a retrospective review. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 252–4.

Malhotra S, Yentis SM. Extending low-dose epidural analgesia in labour for emergency caesarean section—a comparison of levobupivacaine with or without fentanyl. Anaesthesia 2007; 62: 667–71.

Halpern SH, Soliman A, Yee J, Angle P, Ioscovich A. Conversion of epidural labour analgesia to anaesthesia for caesarean section: a prospective study of the incidence and determinants of failure. Br J Anaesth 2009; 102: 240–3.

Tortosa JC, Parry NS, Mercier FJ, Mazoit JX, Benhamou D. Efficacy of augmentation of epidural analgesia for caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 532–5.

Sanders RD, Mallory S, Lucas DN, Chan T, Yeo S, Yentis SM. Extending low-dose epidural analgesia for emergency caesarean section using ropivacaine 0.75%. Anaesthesia 2004; 59: 988–92.

Lucas DN, Ciccone GK, Yentis SM. Extending low-dose epidural analgesia for emergency caesarean section. A comparison of three solutions. Anaesthesia 1999; 54: 1173–7.

Orbach-Zinger S, Friedman L, Avramovich A, et al. Risk factors for failure to extend labor epidural analgesia to epidural anesthesia for caesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006; 50: 793–7.

Goring-Morris J, Russell IF. A randomised comparison of 0.5% bupivacaine with a lidocaine/epinephrine/fentanyl mixture for epidural top-up for emergency caesarean section after “low-dose” epidural for labour. Int J Obstet Anesth 2006; 15: 109–14.

Riley ET, Papasin J. Epidural catheter function during labor predicts anesthetic efficacy for subsequent Cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth 2002; 11: 81–4.

Regan KJ, O’Sullivan G. The extension of epidural blockade for emergency caesarean section: a survey of current UK practice. Anaesthesia 2008; 63: 136–42.

Gupta A, Enlund G, Bengtsson M, Sjoberg F. Spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section following epidural analgesia in labour: a relative contraindication. Int J Obstet Anesth 1994; 3: 153–6.

Adams TJ, Peter EA, Douglas MJ. Is spinal anesthesia contraindicated after failed epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1995; 81: 659.

Dadarkar P, Philip J, Weidner C, et al. Spinal anesthesia for Cesarean section following inadequate labor epidural analgesia: a retrospective audit. Int J Obstet Anesth 2004; 13: 239–43.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Frank O’Connor for reviewing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Visser, W.A., Dijkstra, A., Albayrak, M. et al. Spinal anesthesia for intrapartum Cesarean delivery following epidural labor analgesia: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 56, 577–583 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-009-9113-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-009-9113-y