Abstract

Introduction

Various methods have been used to interpret the reports of pediatric polypharmacy across the literature. This is the first scoping review that explores outcome measures in pediatric polypharmacy research.

Objectives

The aim of our study was to describe outcome measures assessed in pediatric polypharmacy research.

Methods

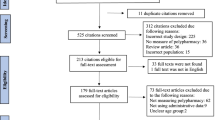

A search of electronic databases was conducted in July 2017, including Ovid Medline, PubMed, Elsevier Embase, Wiley Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EBSCO CINAHL, Ovid PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection, ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis A&I. Data were extracted about study characteristics and outcome measures, and also synthesized by harms or benefits mentioned.

Results

The search strategy initially identified 8169 titles and screened 4398 using the inclusion criteria after de-duplicating. After the primary screening, a total of 363 studies were extracted for the data analysis. Polypharmacy (prevalence) was identified as an outcome in 31.4% of the studies, prognosis-related outcomes in 25.6%, and adverse drug reactions in 16.5%. A total of 265 articles (73.0%) mentioned harms, including adverse drug reactions (26.4%), side effects (24.2%), and drug–drug interactions (20.9%). A total of 83 studies (22.9%) mentioned any benefit, 48.2% of which identified combination for efficacy, 24.1% combination for treatment of complex diseases, and 19.3% combination for treatment augmentation. Thirty-eight studies reported adverse drug reaction as an outcome, where polypharmacy was a predictor, with various designs.

Conclusions

Most studies of pediatric polypharmacy evaluate prevalence, prognosis, or adverse drug reaction-related outcomes, and underscore harms related to polypharmacy. Clinicians should carefully weigh benefits and harms when introducing medications to treatment regimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dai D, Feinstein JA, Morrison W, et al. Epidemiology of polypharmacy and potential drug-drug interactions among pediatric patients in ICUs of US children’s hospitals. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(5):218.

Ahmed B, Nanji K, Mujeeb R, et al. Effects of polypharmacy on adverse drug reactions among geriatric outpatients at a tertiary care hospital in Karachi: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112133.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):989–95.

Helal SI, Megahed HS, Salem SM, et al. Monotherapy versus polytherapy in epileptic adolescents. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):174–7.

Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, et al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2.

Poudel P, Chitlangia M, Pokharel R. Predictors of poor seizure control in children managed at a tertiary care hospital of Eastern Nepal. Iran J Child Neurol. 2016;10(3):48.

Rasu RS, Iqbal M, Hanifi S, et al. Level, pattern, and determinants of polypharmacy and inappropriate use of medications by village doctors in a rural area of Bangladesh. Clin Outcomes Res. 2014;6:515–21.

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, et al. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;63(2):187–95.

Feinstein J, Dai D, Zhong W, et al. Potential drug-drug interactions in infant, child, and adolescent patients in children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e99–108.

Bakaki PM, Horace A, Dawson N, et al. Defining pediatric polypharmacy: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0208047.

Constantine RJ, Boaz T, Tandon R. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of children and adolescents in the fee-for-service component of a large state medicaid program. Clin Ther. 2010;32(5):949–59.

Gallego JA, Nielsen J, De Hert M, et al. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11(4):527.

Lochmann van Bennekom MW, Gijsman HJ, Zitman FG. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in psychotic disorders: a critical review of neurobiology, efficacy, tolerability and cost effectiveness. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(4):327–36.

Rashed AN, Wilton L, Lo CCH, et al. Epidemiology and potential risk factors of drug-related problems in Hong Kong paediatric wards: drug-related problems in paediatric patients in Hong Kong. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(5):873–9.

Sammons HM, Choonara I. Learning lessons from adverse drug reactions in children. Children (Basel). 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/children3010001.

Schall CA. A consumer’s guide to monitoring psychotropic medication for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2002;17(4):229–35.

Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1001–10.

Saldaña SN, Keeshin BR, Wehry AM, et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in children and adolescents at discharge from psychiatric hospitalization. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):836–44.

Golchin N, Isham L, Meropol S, et al. Polypharmacy in the elderly. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4(2):85.

Guthrie B, McCowan C, Davey P, et al. High risk prescribing in primary care patients particularly vulnerable to adverse drug events: cross sectional population database analysis in Scottish general practice. BMJ. 2011;342(7812):1406.

Olashore A, Ayugi J, Opondo P. Prescribing pattern of psychotropic medications in child psychiatric practice in a mental referral hospital in Botswana. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;26:83.

De Ferranti S, Ludwig DS. Storm over statins: the controversy surrounding pharmacologic treatment of children. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1309–12.

Hausner E, Fiszman ML, Hanig J, et al. Long-term consequences of drugs on the paediatric cardiovascular system. Drug Saf. 2008;31(12):1083–96.

Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, et al. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011;33(1):147–50.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48.

Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reaction: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000;356(9237):1255–9.

Smith W. Adverse drug reaction: allergy? Side effect? Intolerance? Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(1–2):12–6.

Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4: software for research synthesis. EPPI-Centre Software. London: Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education. 2010. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/er4/Features/tabid/3396/Default.aspx. Accessed 21 Feb 2019.

Al-Qudah A, Hwang P, Giesbrecht E, et al. Contribution of carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide to neurotoxicity in epileptic children on polytherapy. Jordan Med J. 1991;25(2):171–7.

Allarakhia IN, Garofalo EA, Komarynski MA, et al. Valproic acid and thrombocytopenia in children: a case–controlled retrospective study. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;14(4):303–7.

Amitai M, Sachs E, Zivony A, et al. Effects of long-term valproic acid treatment on hematological and biochemical parameters in adolescent psychiatric inpatients: a retrospective naturalistic study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(5):241.

Anderson M, Egunsola O, Cherrill J, et al. A prospective study of adverse drug reactions to antiepileptic drugs in children. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e008298.

Anghelescu DL, Ross CE, Oakes LL, et al. The safety of concurrent administration of opioids via epidural and intravenous routes for postoperative pain in pediatric oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2008;35(4):412–9.

Bali V, Kamble PS, Aparasu RR. Cardiovascular safety of concomitant use of atypical antipsychotics and long-acting stimulants in children and adolescents with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(2):163–72.

Becker EA, Shafer A, Anderson R. Weight changes in teens on psychotropic medication combinations at Austin state hospital. Tex Med. 2005;101(3):62–70.

Burch KJ. Using a trigger tool to assess adverse drug events in a children’s rehabilitation hospital. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16(3):204.

Cramer JA, Steinborn B, Striano P, et al. Non interventional surveillance study of adverse events in patients with epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(1):13–21.

De Las Salas R, Díaz-Agudelo D, Burgos-Flórez FJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions in hospitalized Colombian children. Colomb Med. 2016;47(3):142–7.

Dos Santos DB, Coelho HLL. Adverse drug reactions in hospitalized children in Fortaleza. Brazil. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(9):635–40.

El-Khayat H, Shatla H, Ali G, et al. Physical and hormonal profile of male sexual development in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44(3):447–52.

El-Rashidy OF, Shatla RH, Youssef OI, et al. Cardiac autonomic balance in children with epilepsy: value of antiepileptic drugs. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52(4):419–23.

Farhat G, Yamout B, Mikati MA, et al. Effect of antiepileptic drugs on bone density in ambulatory patients. Neurology. 2002;58(9):1348–53.

Galas-Zgorzalewicz B, Borysewicz-Lewicka M, Zgorzalewicz M, et al. The effect of chronic carbamazepine, valproic acid and phenytoin medication on the periodontal condition of epileptic children and adolescents. Funct Neurol. 1996;11(4):187–93.

Ghose K, Taylor A. Hypercupraemia induced by antiepileptic drugs. Hum Toxicol. 1983;3:519–29.

Hallioglu O, Okuyaz C, Mert E, et al. Effects of antiepileptic drug therapy on heart rate variability in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2008;79(1):49–54.

Hilt RJ, Chaudhari M, Bell JF, et al. Side effects from use of one or more psychiatric medications in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(2):83–9.

Junger KW, Morita D, Modi AC. The pediatric epilepsy side effects questionnaire: establishing clinically meaningful change. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;45:101–4.

Kaplan EH, Kossoff EH, Bachur CD, et al. Anticonvulsant efficacy in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;58:31–6.

Kim SC, Seol IJ, Kim SJ. Hypohidrosis-related symptoms in pediatric epileptic patients with topiramate. Pediatr Int. 2010;52(1):109–12.

Ko CH, Kong CK, Tse PW. Valproic acid and thrombocytopenia: cross-sectional study. Hong Kong Med J. 2001;7(1):15.

Kwon S, Lee S, Hyun M, et al. The potential for QT prolongation by antiepileptic drugs in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30(2):99–101.

McIntyre RS, Jerrell JM. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse events associated with antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(10):929–35.

Mikati MA, Tarabay H, Khalil A, et al. Risk factors for development of subclinical hypothyroidism during valproic acid therapy. J Pediatr. 2007;151(2):178–81.

Ohtahara S, Yamatogi Y. Erratum to “Safety of zonisamide therapy: prospective follow-up survey”. Seizure. 2004;16(1):87–93.

Otsuka T, Sunaga Y, Hikima A. Urinary N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase and guanidinoacetic acid levels in epileptic patients treated with anti-epileptic drugs. Brain Dev. 1994;16(6):437–40.

Patel A, Chan W, Aparasu RR, et al. Effect of psychopharmacotherapy on body mass index among children and adolescents with bipolar disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):349–58.

Rashed AN, Wilton L, Lo CC, et al. Epidemiology and potential risk factors of drug-related problems in Hong Kong paediatric wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(5):873–9.

Rufo-Campos M, Casas-Fernández C, Martínez-Bermejo A. Long-term use of oxcarbazepine oral suspension in childhood epilepsy: open-label study. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(6):480–5.

Sarajlija A, Djuric M, Tepavcevic DK, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Serbian patients with Rett syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):E1972–8.

Shores LE. Normalization of risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia with the addition of aripiprazole. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(3):42–5.

Sobaniec W, Solowiej E, Kulak W, et al. Evaluation of the influence of antiepileptic therapy on antioxidant enzyme activity and lipid peroxidation in erythrocytes of children with epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(7):558–62.

Tekgul H, Dizdarer G, Demir N, et al. Antiepileptic drug-induced osteopenia in ambulatory epileptic children receiving a standard vitamin D3 supplement. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18(6):585.

Thomé-Souza S, Freitas A, Fiore LA, et al. Lamotrigine and valproate: efficacy of co-administration in a pediatric population. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28(5):360–4.

Unay B, Akin R, Sarici SU, et al. Evaluation of renal tubular function in children taking anti-epileptic treatment. Nephrology (Carlton). 2006;11(6):485–8.

Verrotti A, Greco R, Morgese G, et al. Carnitine deficiency and hyperammonemia in children receiving valproic acid with and without other anticonvulsant drugs. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1999;29(1):36–40.

Wonodi I, Reeves G, Carmichael D, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in children treated with atypical antipsychotic medications. Mov Disord. 2007;22(12):1777–82.

Schmidt D. Drug treatment strategies for epilepsy revisited: starting early or late? One drug or several drugs? Epilept Disord. 2016;18(4):356–66.

Jureidini J, Tonkin A, Jureidini E. Combination pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents: prevalence, efficacy, risks and research needs. Pediatr Drugs. 2013;15(5):377–91.

Papetti L, Nicita F, Granata T, et al. Early add-on immunoglobulin administration in Rasmussen encephalitis: the hypothesis of neuroimmunomodulation. Med Hypotheses. 2011;77(5):917–20.

Gourgari E, Dabelea D, Rother K. Modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease in children with type 1 diabetes: can early intervention prevent future cardiovascular events? Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(12):1–11.

Li R, Lu L, Lin Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of metronidazole monotherapy versus vancomycin monotherapy or combination therapy in patients with Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0137252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137252.

Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarifying adverse drug events. Documentation and reporting. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:795–801.

Jimmy B, Jose J. Patient medication adherence: measures in daily practice. Oman Med J. 2011;26(3):155–9.

Rameekers JG. Behavioural toxicity of medicinal drugs. Practice consequences, incidence and management. Dryg Saf. 1998;18(3):189–208.

Karjalainen EK, Rapasky GA. Molecular changes during acute myeloid leukemia (AML) evolution and identification of novel treatment strategies through molecular stratification. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2016;144:383–436.

Schweitzer I, Tuckwell V, Johnson G. A review of the use of augmentation therapy for the treatment of resistant depression: implications for the clinician. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(3):340–52.

Chaturvedi VP, Mathur AG, Anand AC. Rational drug use: as common as common sense? Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(3):206–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank our expert stakeholders whose contribution at different stages of the project improved our research protocol, data quality, interpretation, and reporting: Dr. Joseph Calabrese, Dr. Faye Gary, Dr. Cynthia Fontanella, and Dr. Mai Pham. We are also grateful to Ms. Xuan Ma and Ms. Courtney Baker who conducted a great amount of study screening, data extraction, data cleaning, quality checks, processing, and analysis. This publication was made possible by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative Cleveland, KL2TR000440 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funding body was not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. Dr. Feinstein was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, under award number K23HD091295. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Golchin, N., Johnson, H., Bakaki, P.M. et al. Outcome measures in pediatric polypharmacy research: a scoping review. Drugs Ther Perspect 35, 447–458 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-019-00650-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-019-00650-8