Abstract

Despite the increasing sophistication of research in autism, some authors refer to a research-to-practice gap in this field. There are large bodies of theoretical work in autism and of work on psychosocial interventions for autism. In this article, we investigate the extent to which researchers evaluate psychosocial interventions for autism from the perspective of the three dominant cognitive autism theories: theory of mind, executive (dys)functioning and central coherence. We believe that we have identified a theory-to-research-to-practice gap, and propose consideration of theory as a standard part of research practice in connection with autism interventions to bridge this gap and enhance the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It has been written that, despite the increasing sophistication of research in autism, the gap between pure and applied research in this field is increasing, i.e. that a disconnect between the knowledge built up by researchers and its applicability in the real world has developed (Reichow et al. 2008). Other authors refer to a research-to-practice gap in autism intervention and of growing evidence that this contributes to a situation where it is rare for effective autism interventions to be implemented successfully in public mental health and education contexts (Dingfelder and Mandell 2011). There is a recognition that integration is crucial to making progress in autism research but that integrated research frameworks invariably overlook the intervention aspect (McGregor et al. 2008). For interventions in autism to be as successful as they should be, it would seem unarguable that these disconnects need to be addressed. Increasing use of evidence-based practice (EBP) is clearly crucial in this respect (Reichow et al. 2008; Wilczynski and Christian 2008). EBP involves using currently best available evidence explicitly and prudently in determining how to intervene with an individual (Sackett et al. 1996). There must be evidence for both the efficacy (whether an intervention works) and effectiveness (whether it has benefits for the individual) of an intervention, two concepts that are considered by some to fall on a continuum (Silverman and Hinshaw 2008).

An intervention is psychosocial if it is ‘aimed at improving people’s well-being (and) uses cognitive, cognitive-behavioural, behavioural and supportive interventions’ (Zimmermann et al. 2009, p. 97). It has been pointed out that psychosocial autism interventions have generally been founded either in theory or empirical evidence of effectiveness or both (Jones and Jordan 2008). This suggests that such interventions would be more likely to be efficacious and effective if founded in both empirical evidence and theory. Whilst theory capable of explaining the cognitive differences in autism would be of obvious importance in connection with cognitively based interventions, it could be argued that all psychosocial interventions in autism should be considered in the light of the cognitive differences that are generally accepted to characterise autism, or ‘the autisms’ to borrow Gillberg’s term (Doan and Fenton 2012; Frith and Happé 1999; Gillberg 2013; Happé and Frith 2006; Kunda and Goel 2008; Mottron et al. 2006) and to reflect those differences as necessary. Later, we describe the three cognitive autism theories that are generally accepted to characterise many of the aspects of cognition in autism, have a substantial evidence base and assume a pivotal role in autism education and training: the theory of mind (ToM), executive (dys)functioning [E(D)F] and central coherence (CC). However, we suspected that theory—whether autism theory or theory of general application applied to autism (e.g. behavioural theory and social learning theory)—would play a lesser role than empirical evidence in support of the majority of psychosocial interventions in autism. Although the primary focus in our study was on the three cognitive theories that have assumed such a prominent position in autism education and training, and have therefore had a major influence on those working in the context of autism in education, healthcare, social care and elsewhere, we sought references to any theory in the studies we reviewed as we believe that all autism support should have a sound theoretical base.

Despite extensive research, there is still no established theoretical framework for autism or an account that captures the definitive nature of autism, although in recent times, the ToM, E(D)F and CC theories of autism have assumed a dominant position in the psychological domain of autism research (Rajendran and Mitchell 2007). These three theories have ‘been hugely influential in understanding different aspects of autism’ (Rajendran 2013), with leading experts in the field acknowledging that they explain many characteristics associated with autism and predict many areas of difficulty experienced in autism (Bowler 2006; Hill and Frith 2003; Rozga et al. 2011). They are supported by extensive empirical evidence (Bowler 2006; Happé 1995; Rutter et al. 2011). Although not a definitive framework, these three theories of autism have assumed a special position in the canon of autism theory, featuring in most, if not all, autism education and training, and being written about extensively in many books on autism.

Theory of mind is the ability to know that others have different thoughts and feelings to one’s own and to be able to understand and predict the feelings of others. When originally applied to autism, it was hypothesised that the social difficulties associated with autism result from an absent or impaired theory of mind (Baron-Cohen et al. 1985). Nowadays, it is unlikely that many people still believe that absence or impairment in theory of mind is the sole cause of autism; it is generally considered to be one of the three ‘key’ theories able to explain some of the cognitive differences between those with autism and those without (Baron-Cohen and Swettenham 1997; Frith and Happé. 1994; Ozonoff et al. 1991; Pellicano 2010). The second of the two dominant cognitive theories of autism is known as executive (dys)functioning. Executive function has been defined as the cognitive functions necessary to enable the self-control necessary to facilitate problem-solving for the attainment of a future goal, and includes planning, impulse control/inhibition, set maintenance, search organisation, working memory and flexibility of thought and action. The executive (dys)functioning hypothesis in autism hypothesises that autism involves difficulties with certain executive functions, including planning, cognitive flexibility and working memory (Ozonoff et al. 1991; Verté et al. 2006). The other dominant cognitive theory of autism is central coherence, which refers to the view that a characteristic of information processing in typically developing people is the tendency to draw together diverse information to understand the whole, known as global processing. The original formulation of the central coherence theory of autism held that, in autism, there is a lack of central coherence resulting in a focus on the detail rather than the whole (local processing), which was classified as weak central coherence (Frith and Happé 1994). But in their later formulation, Happé and Frith (2006) now regard the focus on detail in autism to be a cognitive style or preference, not a weakness. There is a substantial evidence base for the efficacy of these three theories (Bowler 2006; Happé 1995; Rutter et al. 2011).

It would seem reasonable to conclude that evidence-based interventions based on efficacious and effective autism theory would stand a better chance of proving successful in practice than those with no explicit foundation in autism theory and thus, at best, an unclear grounding in cognition characteristic of autism (or ‘the autisms’). Gray explains that human beings interpret the behaviour of others by making a variety of assumptions based on a common social understanding but that these assumptions will be wrong if an individual thinks differently. Attwood and Gray (1999, p. 2) write that these ‘assumptions…may not be applicable to children with an ASD [autism spectrum disorder] who have significant problems with Theory of Mind Skills, Affected Relatedness, Central Coherence and Executive Function’. Gray explains that this makes it difficult for a person with autism and a non-autistic peer to understand each other and interact effectively because the two people are ‘responding with equally valid but different perceptions of the same event’ (Gray 1998, p. 168). The interventions Gray is most closely associated with, and which are widely used as an intervention tool to assist people with autism to understand non-autistic behaviour—social stories and comic strip conversations—are specifically designed to take account of the differences in cognition in autism described by the ToM, E(D)F and CC theories.

An exemplar of an approach to intervention development reflecting theory—both cognitive and behavioural theory—is the social competence intervention (SCI) reported on in Stichter et al. (2010). In this intervention the authors targeted ToM, E(D)F and emotion recognition functioning difficulties in autism with a cognitive behavioural intervention design. They make the point that these difficulties in autism appear to be interrelated and that an integrated (multi-dimensional) intervention is therefore required, specifically targeting the profile of abilities and difficulties (Stichter et al. 2010). They write of their intervention that it:

‘challenges thinking patterns and includes the use of meta-cognitive strategies, self-monitoring and self-regulation, and exposure and response situations…(to address)…idiosyncratic ways of perceiving and understanding emotions, deficits in theory of mind and challenges to executive functioning that inhibit socially competent interactions with others’ (Stichter et al. 2010, p. 1069).

This intervention provided 29 students with a diagnosis and test score criteria consistent with either high functioning autism (HFA) or Asperger syndrome (AS) in seven groups of a maximum of six individuals per group over five semesters with 20 h of group activity undertaken twice weekly for a period of 10 weeks in an after-school clinical setting. The results for two of the students were excluded from the analysis as they had missed more than a quarter of the sessions. The mean age at enrolment was 12.57 years (SD = 1.28; range, 10.83–14.75). All the students were male as no female students diagnosed with HFA or AS were enrolled. The authors’ preliminary report indicated that the SCI intervention was effective in increasing social competence in these students with HFA and AS although the ToM results were mixed.Footnote 1 Parents reported that measures of both social abilities and executive functioning improved as well as in the ability to recognise emotions in facial expressions. The authors consider that their work demonstrates the importance of developing interventions to improve social competence in autism that are specifically designed to reflect the cognitive characteristics of autism (Stichter et al. 2010). Importantly, they call for an increase in interdisciplinary working as a means to develop better autism interventions.

Reichow et al. (2008) stress that reviews critically evaluating the empirical evidence relating to interventions for autism have not found any evidence-based interventions. Whilst their paper was focused on interventions for young children with autism, we have no reason to suppose that the situation is any better for older children or adults, although studies such as that by Stichter et al. (2010) suggest that the social difficulties in autism can be reduced. We surmised that the majority of interventions for autism could also be said either not to reflect autism theory at all or only to reflect it loosely. If autism interventions are only founded in general theory (e.g. social learning theory and behavioural theory), we have to ask whether this will be sufficient. There is a potential for a theory-to-research gap in addition to the already acknowledged research-to-practice gap if theory is not considered. If theory should have informed the design and/or delivery of a specific autism intervention, but was not considered, there would definitely be a theory research to intervention research gap. There remains a risk of interventions not being as effective as they should be if theory is not considered as a matter of course. We wanted to ascertain whether it was standard autism intervention research practice to consider the relevance of theory in general, but of the three dominant cognitive autism theories in particular. If consideration of theory is not standard practice, this is an issue both for theoreticians and intervention researchers, as well as those who have a foot in both camps. It has also been remarked upon that research into interventions in autism may have the potential to inform theory (Jones et al. 2006). These points support a case for: (a) greater collaboration between theoreticians and intervention researchers working in the field of autism, and (b) standard autism research practice to include consideration of the practical application of their theory by theoreticians, and consideration of theory by developers of interventions.

There appears to be no substantial body of work on theory-based (or theory-guided) autism practice as there is for EBP in autism (a non-systematic search for literature on EBP in autism produced over 9000 results, whereas a similar search for theory-based and theory-guided practice produced only 20 results). It is possible that an apparent absence of links between autism theory and practice may be due to the lack of definitive autism theory. But if this is so, we suggest that the situation needs to be acknowledged and acted upon. One response would be for intervention researchers in autism to demonstrate, as part of the ‘proof of concept’ for their intervention, how theory has informed their work. Theoreticians could assist this process by giving consideration to, and reporting on, practical applications of their theory.

Objective

We sought an indication as to the extent to which researchers of interventions in the autism field undertake theoretical justification analysis, which we define as identification of all theory relevant to the design and delivery of an intervention together with demonstration of how the design and delivery of the intervention reflects relevant theory. Our review was not intended to evaluate the scientific quality of the studies reviewed. We hypothesised that:

-

1.

Only a minority of reports on research into psychosocial interventions in autism would include explicit analysis of their theoretical underpinning.

-

2.

Any consideration given to theory would generally not have been to autism theory.

-

3.

In general terms, there would be an autism theory research-to-autism intervention research gap.

Method

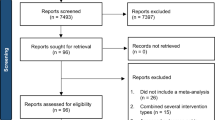

We believe that our simple analysis procedure, which we set out in this section, conforms to the criteria applied to quantitative research, namely internal validity, external validity, reliability and objectivity. Although our subject matter was unstructured descriptive data in study reports, we used a simple quantitative method (summation of references to theory) to evaluate the extent to which the studies explicitly considered theory. We considered this to be appropriate given that our objective was only to seek indications that our hypotheses were correct. Further, more in-depth, qualitative study would be required to confirm our initial indications. Given the logistical difficulties of attempting to develop a random sample of the very many extant autism intervention studies, we decided to adopt an approach to sampling that would produce a reasonably representative sample; we felt that this approach chimed with our indicative aims. Our sampling method equates to cluster sampling in that the groups of study units (clusters) were the groups of studies reviewed in the most recent systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions in autism. In comparison to random sampling, there is a greater probability that our sample will not be fully representative of the total study population (all psychosocial intervention studies in autism). However, the risk of the sample being unrepresentative reduces the more clusters are included, and, after exclusions, we included 19 systematic reviews and 244 studies. As we initially estimated that about 25 % of studies would make reference to theory, the figure of 244 was adequate from a sampling perspective, so we did not add to the 19 systematic reviews remaining from our literature review after we had excluded those considered inappropriate in our context.

To provide an indication of the extent to which researchers of autism interventions undertook theoretical justification analysis, we report in detail on the extent to which they had reported taking into account the three dominant cognitive autism theories—ToM, E(D)F and CC—although we could just as easily have selected other theory for this purpose. However, we took the opportunity to search for explicit references to all theory and report a ‘headline’ finding in this respect for comparison purposes. A simple analytical framework was suitable for our purpose, and we adopted the Search, AppraisaL, Synthesis and Analysis (SALSA) framework (Booth et al. 2012; Grant and Booth 2009). Our search procedure involved identifying all explicit references to the three dominant cognitive theories of autism in the reports of studies reviewed in the 19 systematic reviews. We also searched for references to other theory. The search was followed by appraisal, synthesis and analysis of our data.

The Systematic Reviews Identified via a Search of the Literature

To ensure that we analysed reports of studies included in the most recent systematic reviews, we identified all the systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions in autism from 2012 to date and reviewed all the reports of studies published from 2005 to date included in each systematic review (subject to any necessary exceptions, which we refer to later). We would add earlier systematic reviews to make up the numbers if the initial approach failed to produce a sufficient number of the latest studies to justify drawing conclusions (this proved unnecessary). Twenty-five systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions in autism from 2012 onwards emerged from our search of the literature.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The following set of inclusion/exclusion criteria to determine which systematic reviews and studies should be included in our own review was developed. The list is not definitive though as a different set of systematic reviews might have necessitated different criteria:

-

Articles identified as systematic reviews in the literature review but which were single autism intervention studies, not systematic reviews of a range of interventions

-

Studies of psychosocial interventions for disorders that were co-morbid to autism, not the autism itself, as none of the cognitive theories under consideration would have a direct bearing on the co-morbidity

-

Studies involving cohorts of children with an intellectual disability but without autism

-

Studies that assessed sensory processing interventions for sensory sensitivity in autism as none of the cognitive theories under consideration seek to explain these behaviours (Bailey et al. 1996; Rogers and Ozonoff 2005) so it was a reasonable assumption that these theories would not have informed sensory interventions.

Systematic Reviews Excluded from Our Analysis

Six of the 25 articles our search identified as systematic reviews were excluded on the basis of these criteria. Four articles generated by our search proved to be single intervention studies rather than systematic reviews, one systematic review was focussed on obsessive-compulsive disorder in autism and one systematic review concerned sensory processing interventions. The remaining 19 systematic reviews listed in Table 1 were included in our review.

Intervention Study Reports Excluded from Our Analysis

Of the 370 reports of studies covered by the 19 systematic reviews included in our review, 85 reports were excluded because they had been published prior to our pre-determined cut-off year (2005), 33 reports were excluded to avoid double-counting and eight reports were excluded because the studies to which they referred related to cohorts of children with an intellectual disability, not autism. After these 126 reports were excluded, a total of 244 reports of studies remained for us to review, which was a sufficient number to enable us to draw conclusions, especially given that we only aimed to provide indicative results.

Analysis

We adopted the simple procedure of totalling the number of references to the three dominant cognitive theories of autism in the 244 reports included in our study. It seemed improbable that authors could discuss aspects of autism theory in their report without actually using the relevant terminology (ToM, etc.) so we concluded that a series of searches on the various permutations of each theory (e.g. executive function, executive dysfunction) would provide a sufficiently reliable indication of the extent to which these theories of autism were explicitly considered in the reports of studies we reviewed. Researchers might undertake theoretical analysis without reporting having done so, although it appeared to us unlikely that an acknowledgement of the need to consider autism theory would not be accompanied by a realisation of the importance of reporting the theoretical work. Conversely, a report that made specific reference to one or more theories, but without any theoretical analysis having informed the development of the intervention, would tend to over-estimate the extent to which the theories had been considered. Overall, we felt that our approach would be more likely to over-estimate attention given to autism theory than under-estimate it and that a review of 244 studies would produce reliable indications for our purposes.

Results

Of the 244 studies we investigated from the perspective of their consideration of the three dominant cognitive autism theories, 199 (82 %) did not refer to ToM, 225 (92 %) made no mention of E(D)F and 233 (95 %) did not explicitly consider CC. Put in another way, only about one study in five referred to ToM, one in ten to E(D)F and one in 20 to CC. We analysed the results by year and, although the percentage of studies that referred to ToM reduced each year from 2011 to 2014, this was not statistically significant and no trend emerged. The figures for E(D)F and CC per annum were too small for any trending. Over 95 % of the reports made no explicit reference to theory other than ToM, E(D)F and CC (e.g. behavioural theory). Seventy-three percent of studies reviewed made no explicit reference to any theory.

Discussion

The first indication that we drew from our findings was that discussion of theoretical justification was not included in the large majority of articles reporting on the design and/or delivery of autism interventions. This appears to confirm our hypothesis that a minority of research into psychosocial interventions in autism would report on analysis of the theoretical underpinning of the interventions or analysis of theory informing the deployment of interventions. The second indication, which appeared to follow logically from the first indication, was that theoretical justification appears not generally to be considered an important factor in the development of autism interventions by scholars, or at least in the reporting of autism intervention studies (and we think it unlikely that theoretical analysis would be undertaken but not reported). Thirdly, the large majority of reports of interventions did not refer to any of the three autism theories we were interested in; ToM was referred to more often than either E(D)F or CC but only in about one in every five reports. Our hypothesis that where theory was considered, it would generally not be autism theory proved incorrect though as there were more references to autism theories than to other theory. Theoretical analysis may have been undertaken in some cases but not reported; we identified publications in report reference lists that referred to the dominant cognitive autism theories although no mention was made of the theory in the main body text. In summary, only a relatively small percentage of autism intervention study reports appeared to consider interventions from the perspective of one or more of the dominant cognitive theories of autism featured heavily in textbooks, education and training. The indications are that there is an autism theory research-to-autism intervention research gap in that theoretical analysis is not standard practice in psychosocial autism intervention research and theoreticians do not generally consider practice.

We have asked ourselves why researchers of psychosocial interventions in autism would not consider autism theory as an integral and important part of their work; indeed, why they would not put autism theory at the heart of their work in autism? If interventions are to help to overcome difficulties in autism, and if current autism theory adequately explains many of those difficulties, it would seem to be an essential requirement for interventions to be considered from a theoretical perspective, and hence an issue if they are not. Even if an intervention is not directly aimed at overcoming difficulties in autism arising from issues around ToM, E(D)F and/or CC, it may be necessary to consider theory in relation to the deployment of the intervention given that planning difficulties, for example, may affect the ability of a person with autism to play their role effectively in an intervention. If the apparent general lack of consideration given to autism theory is due to the absence of definitive theory, the point is rarely, if ever, made by researchers of autism interventions.

Does Howlin’s (2010) identification of the different theoretical perspectives grounding the work of scholars, coupled with the lack of a definitive theoretical basis for autism, contain a clue as to why autism theory appears not to be considered very often? However, whilst researchers of autism interventions are in the invidious position of not having a definitive body of autism-specific theory to refer to, there is a body of generally accepted autism-specific theory, as well as general theory such as learning theory and behavioural theory, none of which is referred to regularly. To balance the books, we doubt that the work of theoreticians will often consider the practical applications of their theory.

We believe that there should be an increased focus on theory in relation to psychosocial autism interventions in order to close the theory-to-research-to-practice gap we think we have identified. In the continuing absence of a definitive theoretical framework for autism, we believe that psychosocial intervention studies in autism should consider if the efficacy and effectiveness of the intervention under development would be enhanced if its design and delivery reflected relevant behavioural, cognitive and learning theory. As Jones et al. (2006) suggest, this approach may also help with the validation and development of theory.

Limitations

The primary limitation of our study is that we only sought an indication of the extent to which autism intervention researchers consider theory in their work, and that the 244 reports of studies we reviewed represents only a small proportion of the studies undertaken in the decade from 2005. As reports may mention one or more theories without robust theoretical analysis having been carried out, our figures are likely to be over-estimates of the extent to which theoretical justification analysis is undertaken. Although we consider that our approach provides a sufficiently reliable indication to justify its use in support of our main hypothesis, our findings are only indications and should be treated as such. Nevertheless, our cluster sampling approach is less representative of a population than random sampling. Random sampling would have been exceedingly difficult to achieve in practice given that our population was the entirety of reports of studies into psychosocial interventions in autism. Although we followed the World Health Organisation guidance on sampling, our approach to sampling is a limitation of the study. No assessment of the rater’s reliability was undertaken to establish their accuracy. Despite no coding being involved—only a detailed word search—the absence of any inter-rater evaluation is a further limitation of this study since mistakes could have been made in the search. Finally, we did not review any reports of studies published prior to 2005. The application of ToM, E(D)F and CC to autism date from 1985, 1969 and 1994, respectively (Baron-Cohen et al. 1985; Frith and Happé 1994; Wing 1969). We would expect that references to these theories would have initially increased as awareness of them spread amongst researchers but that a good general awareness of them would have been achieved before our 2005 cut-off year, i.e. that our findings reflect mature awareness of the three theories. The current version of CC theory dates from 2006 (Happé and Frith 2006), so any references to this theory prior to our search period could not reflect the later version of this theory.

Notes

Strangely, fewer members of the Stichter et al. (2010) student cohort passed first- and second-order ToM tests post-intervention than pre-intervention.

References

References preceded by an asterisk (*) indicate the studies included in our review.

* Ahearn, W. H. (2003). Using simultaneous presentation to increase vegetable consumption in a mildly selective child with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(3), 361–365. doi:10.1901/jaba.2003.36-361.

* Allen, K. D., Wallace, D. P., Greene, D. J., Bowen, S. L., & Burke, R. V. (2010a). Community-based vocational instruction using videotaped modeling for young adults with autism spectrum disorders performing in air-inflated mascots. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25(3), 186–192. doi:10.1177/1088357610377318.

* Allen, K. D., Wallace, D. P., Renes, D., Bowen, S. L., & Burke, R. V. (2010b). Use of video modeling to teach vocational skills to adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Treatment of Children, 33(3), 339–349. doi:10.1353/etc.0.0101.

* Allor, J. H., Mathes, P. G., Roberts, J. K., Cheatham, J. P., & Champlin, T. M. (2010). Comprehensive reading instruction for students with intellectual disabilities: Findings from the first three years of a longitudinal study. Psychology in the Schools, 47(5), 445–466. doi:10.1002/pits.20482.

* Anglesea, M. M., Hoch, H., & Taylor, B. A. (2008). Reducing rapid eating in teenagers with autism: Use of a pager prompt. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(1), 107–111. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.41-107.

* Argott, P., Townsend, D. B., Sturmey, P., & Poulson, C. L. (2008). Increasing the use of empathic statements in the presence of a non-verbal affective stimulus in adolescents with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2(2), 341–352. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2007.08.004.

Attwood, T., & Gray, C. (1999). Understanding and teaching friendship skills. Retrieved from http://www.tonyattwood.com.au/index.php/publications/by-tony-attwood/archived-papers/75-understanding-and-teachingfriendship-skills.

Bailey, A., Phillips, W., & Rutter, M. (1996). Autism: Towards an integration of clinical, genetic, neuropsychological, and neurobiological perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37, 89–126. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01381.x.

* Baker, D. J., Valenzuela, S., & Wieseler, N. A. (2005). Naturalistic inquiry and treatment of coprophagia in one individual. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 17(4), 361–367. doi:10.1007/s10882-005-6619-2.

* Banda, D. R., Copple, K. S., Koul, R. K., Sancibrian, S. L., & Bogschutz, R. J. (2010). Video modelling interventions to teach spontaneous requesting using AAC devices to individuals with autism: A preliminary investigation. Disability & Rehabilitation, 32(16), 1364–1372. doi:10.3109/09638280903551525.

Baron-Cohen, S., & Swettenham, J. (1997). Theory of mind in autism: Its relationship to executive function and central coherence. In Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (pp. 880–893). New York: Wiley.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition, 21(1), 37–46.

* Basil, C., & Reyes, S. (2003). Acquisition of literacy skills by children with severe disability. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 19(1), 27–48. doi:10.1191/0265659003ct242oa.

* Beaumont, R., & Sofronoff, K. (2008). A multi‐component social skills intervention for children with Asperger syndrome: The Junior Detective Training Program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(7), 743–753. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01920.x.

* Begeer, S., Gevers, C., Clifford, P., Verhoeve, M., Kat, K., Hoddenbach, E., & Boer, F. (2011). Theory of mind training in children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(8), 997–1006. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1121-9.

* Bennett, K. D., & Dukes, C. (2014). A systematic review of teaching daily living skills to adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1(1), 2–10. doi:10.1007/s40489-013-0004-3.

* Bereznak, S., Ayres, K. M., Mechling, L. C., & Alexander, J. L. (2012). Video self-prompting and mobile technology to increase daily living and vocational independence for students with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(3), 269–285. doi:10.1007/s10882-012-9270-8.

* Betz, A., Higbee, T. S., & Reagon, K. A. (2008). Using joint activity schedules to promote peer engagement in preschoolers with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(2), 237–241. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.41-237.

* Betz, A. M., Higbee, T. S., & Pollard, J. S. (2010). Promoting generalization of mands for information used by young children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(3), 501–508. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.11.007.

* Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L., Minshew, N. J., & Eack, S. M. (2014). A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders. In Adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders (pp. 315–327). Springer: New York.

* Blakeley-Smith, A., Carr, E. G., Cale, S. I., & Owen-DeSchryver, J. S. (2009). Environmental fit: A model for assessing and treating problem behavior associated with curricular difficulties in children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(3), 131–145. doi:10.1177/1088357609339032.

* Bloh, C. (2008). Assessing transfer of stimulus control procedures across learners with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 24(1), 87. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2779927/.

* Bölte, S., Feineis-Matthews, S., Leber, S., Dierks, T., Hubl, D., & Poustka, F. (2002). The development and evaluation of a computer-based program to test and to teach the recognition of facial affect. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 61. Retrieved from http://www.circumpolarhealthjournal.net/index.php/ijch/article/viewFile/17503/19912.

* Boesch, M. C., Wendt, O., Subramanian, A., & Hsu, N. (2013). Comparative efficacy of the picture exchange communication system (PECS) versus a speech-generating device: Effects on social-communicative skills and speech development. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29(3), 197–209. doi:10.3109/07434618.2013.818059.

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: Sage.

* Bosseler, A., & Massaro, D. W. (2003). Development and evaluation of a computer-animated tutor for vocabulary and language learning in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(6), 653–672. doi:10.1023/B:JADD.0000006002.82367.4f.

* Boudreau, E., & D’Entremont, B. (2010). Improving the pretend play skills of preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders: The effects of video modeling. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 22(4), 415–431. doi:10.1007/s10882-010-9201-5.

* Bouxsein, K. J., Tiger, J. H., & Fisher, W. W. (2008). A comparison of general and specific instructions to promote task engagement and completion by a young man with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(1), 113–116. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.41-113.

Bowler, D. (2006). Autism spectrum disorders: Psychological theory and research. New York: Wiley.

* Brookman-Frazee, L. I., Drahota, A., & Stadnick, N. (2012). Training community mental health therapists to deliver a package of evidence-based practice strategies for school-age children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(8), 1651–1661. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1406-7.

* Browder, D. M., Trela, K., & Jimenez, B. (2007). Training teachers to follow a task analysis to engage middle school students with moderate and severe developmental disabilities in grade-appropriate literature. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22(4), 206–219. doi:10.1177/10883576070220040301.

* Browder, D., Ahlgrim-Delzell, L., Flowers, C., & Baker, J. (2012). An evaluation of a multicomponent early literacy program for students with severe developmental disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 33(4), 237–246. doi:10.1177/0741932510387305.

* Brown, K. E., & Mirenda, P. (2006). Contingency mapping use of a novel visual support strategy as an adjunct to functional equivalence training. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(3), 155–164. doi:10.1177/10983007060080030401.

* Bryan, L. C., & Gast, D. L. (2000). Teaching on-task and on-schedule behaviors to high-functioning children with autism via picture activity schedules. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(6), 553–567. doi:10.1023/A:1005687310346.

* Burke, R. V., Andersen, M. N., Bowen, S. L., Howard, M. R., & Allen, K. D. (2010). Evaluation of two instruction methods to increase employment options for young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(6), 1223–1233. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.07.023.

* Buschbacher, P., Fox, L., & Clarke, S. (2004). Recapturing desired family routines: A parentprofessional behavioral collaboration. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 29(1), 25–39. doi:10.2511/rpsd.29.1.25.

* Caballero, A., & Connell, J. E. (2010). Evaluation of the effects of social cue cards for preschool age children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Journal of Behavior Assessment and Intervention in Children, 1(1), 25. doi:10.1037/h0100358.

* Cardon, T. A. (2012). Teaching caregivers to implement video modeling imitation training via iPad for their children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(4), 1389–1400. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2012.06.002.

* Cardon, T. A., & Wilcox, M. J. (2011). Promoting imitation in young children with autism: A comparison of reciprocal imitation training and video modeling. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 654–666. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1086-8.

* Carter, A. S., Messinger, D. S., Stone, W. L., Celimli, S., Nahmias, A. S., & Yoder, P. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of Hanen’s ‘More Than Words’ in toddlers with early autism symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(7), 741–752. doi:111/j.1469-7610.2011.02395.x.

* Case-Smith, J., Weaver, L. L., & Fristad, M. A. (2014). A systematic review of sensory processing interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. doi:10.1177/1362361313517762

* Chalfant, A. M., Rapee, R., & Carroll, L. (2007). Treating anxiety disorders in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: A controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1842–1857. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0318-4.

* Chan, J. M., & O’Reilly, M. F. (2008). A Social Stories™ intervention package for students with autism in inclusive classroom settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(3), 405–409. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.41-405.

* Charlop, M. H., Gilmore, L., & Chang, G. T. (2008). Using video modeling to increase variation in the conversation of children with autism. Journal of Special Education Technology, 23(3), 47. Retrieved from http://lcproxy.shu.ac.uk/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.lcproxy.shu.ac.uk/docview/228533262?accountid=13827.

* Choi, H., O’Reilly, M., Sigafoos, J., & Lancioni, G. (2010). Teaching requesting and rejecting sequences to four children with developmental disabilities using augmentative and alternative communication. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(2), 560–567. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.12.006.

* Chok, J. T., Reed, D. D., Kennedy, A., & Bird, F. L. (2010). A single-case experimental analysis of the effects of ambient prism lenses for an adolescent with developmental disabilities. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 3(2), 42. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3004691/.

* Cihak, D. F. (2007). Teaching students with autism to read pictures. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(4), 318–329. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2006.12.002.

* Cihak, D. F. (2011). Comparing pictorial and video modeling activity schedules during transitions for students with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 433–441. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.006.

* Cihak, D. F., & Grim, J. (2008). Teaching students with autism spectrum disorder and moderate intellectual disabilities to use counting-on strategies to enhance independent purchasing skills. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2(4), 716–727. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.02.006.

* Clarke, S., Dunlap, G., & Vaughn, B. (1999). Family-centered, assessment-based intervention to improve behavior during an early morning routine. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1(4), 235–241. doi:10.1177/109830079900100406

* Cohen, H., Amerine-Dickens, M., & Smith, T. (2006). Early intensive behavioral treatment: Replication of the UCLA model in a community setting. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(2), S145–S155. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/jrnldbp/Abstract/2006/04002/Early_Intensive_Behavioral_Treatment__Replication.13.aspx.

* Coleman-Martin, M. B., Heller, K. W., Cihak, D. F., & Irvine, K. L. (2005). Using computer-assisted instruction and the nonverbal reading approach to teach word identification. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(2), 80–90.

* Corbett, B. A., Gunther, J. R., Comins, D., Price, J., Ryan, N., Simon, D., … & Rios, T. (2011). Brief report: Theatre as therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(4), 505–511. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1064-1.

* Cotugno, A. J. (2009). Social competence and social skills training and intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(9), 1268–1277. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0741-4.

* D’Ateno, P., Mangiapanello, K., & Taylor, B. A. (2003). Using video modeling to teach complex play sequences to a preschooler with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5(1), 5–11. doi:10.1177/10983007030050010801.

* Dauphin, M., Kinney, E. M., Stromer, R., & Koegel, R. L. (2004). Using video-enhanced activity schedules and matrix training to teach sociodramatic play to a child with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 6(4), 238–250. doi:10.1177/10983007040060040501.

* Davis, K. M., Boon, R. T., Cihak, D. F., & Fore III, C. (2010). Power cards to improve conversational skills in adolescents with Asperger syndrome, Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25(1), 12–22. doi:10.1177/1088357609354299.

* Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J., Greenson, J., … & Varley, J. (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125(1), e17–e23. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0958.

* Deitchman, C., Reeve, S. A., Reeve, K. F., & Progar, P. R. (2010). Incorporating video feedback into self-management training to promote generalization of social initiations by children with autism. Education and Treatment of Children, 33(3), 475–488. doi:10.1353/etc.0.0102.

* Delano, M. E. (2007a). Use of strategy instruction to improve the story writing skills of a student with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22(4), 252–258. doi:10.1177/10883576070220040701.

* Delano, M. E. (2007b). Improving written language performance of adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 40(2), 345–351. doi:10.1901/jaba.2007.50-06.

* DeLeon, I. G., Hagopian, L. P., Rodriguez‐Catter, V., Bowman, L. G., Long, E. S., & Boelter, E. W. (2008). Increasing wearing of prescription glasses in individuals with mental retardation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(1), 137–142. doi:10.1901/jaba.2008.41-137.

* DeRosier, M. E., Swick, D. C., Davis, N. O., McMillen, J. S., & Matthews, R. (2011). The efficacy of a social skills group intervention for improving social behaviors in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(8), 1033–1043. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1128-2.

* Dettmer, S., Simpson, R. L., Myles, B. S., & Ganz, J. B. (2000). The use of visual supports to facilitate transitions of students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15(3), 163–169. doi:10.1177/108835760001500307.

Dingfelder, H. E., & Mandell, D. S. (2011). Bridging the research-to-practice gap in autism intervention: An application of diffusion of innovation theory. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 597–609. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1081-0.

Doan, M., & Fenton, A. (2012). Embodying autistic cognition: Towards re-conceiving certain ‘autism-related’ behavioural atypicalities as functional. In J. L. Anderson & S. Cushing (Eds.), The philosophy of autism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

* Dodd, S., Hupp, S. D., Jewell, J. D., & Krohn, E. (2008). Using parents and siblings during a social story intervention for two children diagnosed with PDD-NOS. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 20(3), 217–229. doi:10.1007/s10882-007-9090-4.

* Dooley, P., Wilczenski, F. L., & Torem, C. (2001). Using an activity schedule to smooth school transitions. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3(1), 57–61. doi:10.1177/109830070100300108.

* Dotson, W. H., Leaf, J. B., Sheldon, J. B., & Sherman, J. A. (2010). Group teaching of conversational skills to adolescents on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 199–209. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.005.

* Dotto-Fojut, K. M., Reeve, K. F., Townsend, D. B., & Progar, P. R. (2011). Teaching adolescents with autism to describe a problem and request assistance during simulated vocational tasks. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(2), 826–833. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.09.012.

* Dugan, K. T. (2006). Facilitating independent behaviors in children with autism employing picture activity schedules. Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University.

* Dupere, S., MacDonald, R. P., & Ahearn, W. H. (2013). Using video modeling with substitutable loops to teach varied play to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(3), 662–668. doi:10.1002/jaba.68.

* Ehrenreich-May, J., Storch, E. A., Queen, A. H., Rodriguez, J. H., Ghilain, C. S., Alessandri, M., … & Wood, J. J. (2014). An open trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 1–11. doi:10.1177/1088357614533381.

* Eikeseth, S., Smith, T., Jahr, E., & Eldevik, S. (2007). Outcome for children with autism who began intensive behavioral treatment between ages 4 and 7 a comparison controlled study. Behavior modification, 31(3), 264–278. doi:10.1177/0145445506291396.

* Eikeseth, S., Klintwall, L., Jahr, E., & Karlsson, P. (2012). Outcome for children with autism receiving early and intensive behavioral intervention in mainstream preschool and kindergarten settings. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 829–835. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.002.

* Endicott, K., & Higbee, T. S. (2007). Contriving motivating operations to evoke mands for information in preschoolers with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(3), 210–217. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2006.10.003

* Epp, K. M. (2008). Outcome-based evaluation of a social skills program using art therapy and group therapy for children on the autism spectrum. Children & Schools, 30(1), 27–36. doi:10.1093/cs/30.1.27.

* Faja, S., Aylward, E., Bernier, R., & Dawson, G. (2007). Becoming a face expert: A computerized face-training program for high-functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Neuropsychology, 33(1), 1–24. doi:10.1080/87565640701729573.

* Faja, S., Webb, S. J., Jones, E., Merkle, K., Kamara, D., Bavaro, J., … & Dawson, G. (2012). The effects of face expertise training on the behavioral performance and brain activity of adults with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42(2), 278–293. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1243-8.

* Ferguson, H., Myles, B. S., & Hagiwara, T. (2005). Using a personal digital assistant to enhance the independence of an adolescent with Asperger syndrome. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 60–67. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.lcproxy.shu.ac.uk/discover/10.2307/23879772?sid=21105440149051&uid=5910784&uid=3&uid=34514&uid=3738032&uid=67&uid=2&uid=34516&uid=62.

* Ferraioli, S. J., & Harris, S. L. (2011). Teaching joint attention to children with autism through a sibling‐mediated behavioral intervention. Behavioral Interventions, 26(4), 261–281. doi:10.1002/bin.336.

* Flanagan, H. E., Perry, A., & Freeman, N. L. (2012). Effectiveness of large-scale community-based intensive behavioral Intervention: A waitlist comparison study exploring outcomes and predictors. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 673–682. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.011.

* Flores, M., Musgrove, K., Renner, S., Hinton, V., Strozier, S., Franklin, S., & Hil, D. (2012). A comparison of communication using the Apple iPad and a picture-based system. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28(2), 74–84. doi:10.3109/07434618.2011.644579.

* Fragale, C. L. (2014). Video modeling interventions to improve play skills of children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic literature review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1(3), 165–178. doi:10.1007/s40489-014-0019-4.

* Friedman, A., & Luiselli, J. K. (2008). Excessive daytime sleep behavioral assessment and intervention in a child with autism. Behavior Modification, 32(4), 548–555. doi:10.1177/0145445507312187

Frith, U., & Happé, F. (1994). Autism: Beyond “theory of mind”. Cognition, 50(1), 115–132. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(94)90024-8.

Frith, U., & Happé, F. (1999). Theory of mind and self-consciousness: What is it like to be autistic? Mind and Language, 14, 1–22. doi:10.1111/1468-0017.00100.

* Fujii, C., Renno, P., McLeod, B. D., Lin, C. E., Decker, K., Zielinski, K., & Wood, J. J. (2013). Intensive cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in school-aged children with autism: A preliminary comparison with treatment-as-usual. School Mental Health, 5(1), 25–37. doi:10.1007/s12310-012-9090-0.

* Gabriels, R. L., Agnew, J. A., Holt, K. D., Shoffner, A., Zhaoxing, P., Ruzzano, S., … & Mesibov, G. (2012). Pilot study measuring the effects of therapeutic horseback riding on school-age children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 578–588. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.007.

* Gantman, A., Kapp, S. K., Orenski, K., & Laugeson, E. A. (2012). Social skills training for young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42(6), 1094–1103. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1350-6.

* Ganz, J. B., Simpson, R. L., & Corbin-Newsome, J. (2008). The impact of the Picture Exchange Communication System on requesting and speech development in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders and similar characteristics. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2(1), 157–169. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2007.04.005.

* García‐Villamisar, D. A., & Dattilo, J. (2010). Effects of a leisure programme on quality of life and stress of individuals with ASD. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(7), 611–619. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01289.x

* García‐Villamisar, D., & Hughes, C. (2007). Supported employment improves cognitive performance in adults with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(2), 142–150. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00854.x.

Gillberg, C. (2013). How severe is autism—really? Key note speech to the International Meeting for Autism Research conference, San Sebastián, Spain. Retrieved from http://gnc.gu.se/english/events/past-conferences/imfar-conference-2013.

* Golan, O., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2006). Systemizing empathy: Teaching adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism to recognize complex emotions using interactive multimedia. Development and psychopathology, 18(02), 591–617. doi:10.1017/S0954579406060305.

* Golan, O., Baron-Cohen, S., Hill, J. J., & Golan, Y. (2006). The “reading the mind in films” task: Complex emotion recognition in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions. Social Neuroscience, 1(2), 111–123. doi:10.1080/17470910600980986.

* Graetz, J. E., Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (2009). Decreasing inappropriate behaviors for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders using modified social stories. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44(1), 91. Retrieved from: http://daddcec.org/Portals/0/CEC/Autism_Disabilities/Research/Publications/Education_Training_Development_Disabilities/2009v44_Journals/ETDD_200903v44n1p091-104_Decreasing_Inappropriate_Behaviors_Adolescents_With_Autism.pdf

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Gray, C. (1998). Social stories and comic strip conversations with students with Asperger syndrome and high functioning autism. In E. Schopler, G. Mesibov, & L. Kunce (Eds.), Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism? (pp. 167–198). New York: Plenum Press.

* Hagopian, L. P., Kuhn, D. E., Strother, G. E., & Houten, R. (2009). Targeting social skills deficits in an adolescent with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(4), 907–911. doi:10.1901/jaba.2009.42-907.

* Hall, L. J., McClannahan, L. E., & Krantz, P. J. (1995). Promoting independence in integrated classrooms by teaching aides to use activity schedules and decreased prompts. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 208–217.

* Hansen, S. G., Blakely, A. W., Dolata, J. K., Raulston, T., & Machalicek, W. (2014). Children with autism in the inclusive preschool classroom: A systematic review of single-subject design interventions on social communication skills. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1(3), 192–206. doi:10.1007/s40489-014-0020-y.

Happé, F. (1995). Autism: An introduction to psychological theory. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2006). The weak coherence account: Detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 5–25. doi:10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0.

* Herbrecht, E., Poustka, F., Birnkammer, S., Duketis, E., Schlitt, S., Schmötzer, G., & Bölte, S. (2009). Pilot evaluation of the Frankfurt Social Skills Training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 18(6), 327–335. doi:10.1007/s00787-008-0734-4

* Hetzroni, O. E., & Shalem, U. (2005). From logos to orthographic symbols: A multilevel fading computer program for teaching nonverbal children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(4), 201–212. doi:10.1177/10883576050200040201.

Hill, E. L., & Frith, U. (2003). Understanding autism: Insights from mind and brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358(1430), 281–289. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1209.

* Hillier, A., Campbell, H., Mastriani, K., Izzo, M. V., Kool-Tucker, A. K., Cherry, L., & Beversdorf, D. Q. (2007). Two-year evaluation of a vocational support program for adults on the autism spectrum. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 30(1), 35–47. doi:10.1177/08857288070300010501.

* Hillier, A. J., Greher, G., Poto, N., & Dougherty, M. (2011). Positive outcomes following participation in a music intervention for adolescents and young adults on the autism spectrum. Psychology of Music. doi:10.1177/0305735610386837.

* Hilton, J. C., & Seal, B. C. (2007). Brief report: Comparative ABA and DIR trials in twin brothers with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(6), 1197–1201. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0258-z.

* Hine, J. F., & Wolery, M. (2006). Using point-of-view video modeling to teach play to preschoolers with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26(2), 83–93. doi:10.1177/02711214060260020301

* Howard, J. S., Sparkman, C. R., Cohen, H. G., Green, G., & Stanislaw, H. (2005). A omparison of intensive behavior analytic and eclectic treatments for young children with autism. Research in developmental disabilities, 26(4), 359–383. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2004.09.005.

Howlin, P. (2010). Evaluating psychological treatments for children with autism-spectrum disorders. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 16(2), 133–140. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.109.006684.

* Hume, K., & Odom, S. (2007). Effects of an individual work system on the independent functioning of students with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(6), 1166–1180. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0260-5.

* Ingersoll, B., & Schreibman, L. (2006). Teaching reciprocal imitation skills to young children with autism using a naturalistic behavioral approach: Effects on language, pretend play, and joint attention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(4), 487–505. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0089-y.

* Ingersoll, B. R., & Wainer, A. L. (2013). Pilot study of a school-based parent training program for preschoolers with ASD. Autism, 17(4), 434–448. doi:10.1177/1362361311427155.

* Ingersoll, B., Dvortcsak, A., Whalen, C., & Sikora, D. (2005). The effects of a developmental, social–pragmatic language intervention on rate of expressive language production in young children with autistic spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(4), 213–222. doi:10.1177/10883576050200040301.

* Ingvarsson, E. T., & Hollobaugh, T. (2010). Acquisition of intraverbal behavior: Teaching children with autism to mand for answers to questions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(1), 1–17. doi:10.1901/jaba.2010.43-1.

* Jennett, H. K., Harris, S. L., & Delmolino, L. (2008). Discrete trial instruction vs. mand training for teaching children with autism to make requests. The Analysis of verbal behavior, 24(1), 69. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2779923/pdf/anvb-24-01-69.pdf

Jones, G., & Jordan, R. (2008). Research base for intervention in autism spectrum disorders. In E. McGregor, M. Nunez, K. Cebula, & J. C. Gomez (Eds.), Autism: An integrated view from neurocognitive, clinical, and intervention research (pp. 281–302). Malden: Blackwell.

* Jones, E. A., Carr, E. G., & Feeley, K. M. (2006). Multiple effects of joint attention intervention for children with autism. Behavior Modification, 30(6), 782–834. doi:10.1177/0145445506289392.

* Jung, S. (2008). Using high-probability request sequences to increase social interactions in young children with autism, Doctoral thesis, Ohio State University, Ohio, USA. Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/ap/10?0::NO:10:P10_ACCESSION_NUM:osu1062126243

* Jung, S., Sainato, D. M., & Davis, C. A. (2008). Using high-probability request sequences to increase social interactions in young children with autism. Journal of Early Intervention, 30(3), 163–187. doi:10.1177/1053815108317970.

* Kaale, A., Smith, L., & Sponheim, E. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of preschool‐based joint attention intervention for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(1), 97–105. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02450.x.

* Kagohara, D. M., van der Meer, L., Achmadi, D., Green, V. A., O’Reilly, M. F., Mulloy, A., … & Sigafoos, J. (2010). Behavioral intervention promotes successful use of an iPod-based communication device by an adolescent with autism. Clinical Case Studies, 9(5), 328–338. doi:10.1177/1534650110379633.

* Kashinath, S., Woods, J., & Goldstein, H. (2006). Enhancing generalized teaching strategy use in daily routines by parents of children with autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49(3), 466–485. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2006/036).

* Kassardjian, A., Leaf, J. B., Ravid, D., Leaf, J. A., Alcalay, A., Dale, S., … & Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L. (2014). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories: A replication study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2329–2340. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2103-0.

* Kay, S., Harchik, A. E., & Luiselli, J. K. (2006). Elimination of drooling by an adolescent student with autism attending public high school. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(1), 24–28. doi:10.1177/10983007060080010401.

* Keehn, R. H. M., Lincoln, A. J., Brown, M. Z., & Chavira, D. A. (2013). The coping cat program for children with anxiety and autism spectrum disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(1), 57–67. doi:10.1007/s10803.

* Kempe, A., & Tissot, C. (2012). The use of drama to teach social skills in a special school setting for students with autism. Support for Learning, 27(3), 97–102. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9604.2012.01526.x.

* Kenworthy, L., Anthony, L. G., Naiman, D. Q., Cannon, L., Wills, M. C., Luong‐Tran, C., … & Wallace, G. L. (2014). Randomized controlled effectiveness trial of executive function intervention for children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(4), 374–383. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12161.

* Kern, P., & Aldridge, D. (2006). Using embedded music therapy interventions to support outdoor play of young children with autism in an inclusive community-based child care program. Journal of Music Therapy, 43(4), 270–294. doi:10.1093/jmt/43.4.270.

* Khowaja, K., & Salim, S. S. (2013). A systematic review of strategies and computer-based intervention (CBI) for reading comprehension of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(9), 1111–1121. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2013.05.009.

* Kleeberger, V., & Mirenda, P. (2008). Teaching generalized imitation skills to a preschooler with autism using video modeling. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. doi:10.1177/1098300708329279

* Koegel, R. L., Vernon, T. W., & Koegel, L. K. (2009). Improving social initiations in young children with autism using reinforcers with embedded social interactions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(9), 1240–1251. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0732-5.

* Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., Green-Hopkins, I., & Barnes, C. C. (2010). Brief report: Question-asking and collateral language acquisition in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4), 509–515. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0896-z.

* Koegel, L. K., Vernon, T. W., Koegel, R. L., Koegel, B. L., & Paullin, A. W. (2012). Improving social engagement and initiations between children with autism spectrum disorder and their peers in inclusive settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. doi:10.1177/1098300712437042.

* Krantz, P. J., MacDuff, M. T., & McClannahan, L. E. (1993). Programming participation in family activities for children with autism: Parents’ use of photographic activity schedules. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 137–138. doi:10.1901/jaba.1993.26-137.

* Krstovska-Guerrero, I., & Jones, E. A. (2013). Joint attention in autism: Teaching smiling coordinated with gaze to respond to joint attention bids. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(1), 93–108. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2012.07.007.

* Kuhn, D. E., Hardesty, S. L., & Sweeney, N. M. (2009). Assessment and treatment of excessive straightening and destructive behavior in an adolescent diagnosed with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(2), 355–360. doi:10.1901/jaba.2009.42-355.

* Kunda, M., & Goel, A. K. (2008). How thinking in pictures can explain many characteristic behaviors of autism. In Development and Learning, 2008. ICDL 2008. 7th IEEE International Conference on (pp. 304–309). IEEE. doi:10.1109/DEVLRN.2008.4640847.

* Lacava, P. G., Rankin, A., Mahlios, E., Cook, K., & Simpson, R. L. (2010). A single case design evaluation of a software and tutor intervention addressing emotion recognition and social interaction in four boys with ASD. Autism, 1–18. doi:10.1177/1362361310362085.

* Landa, R. J., Holman, K. C., O’Neill, A. H., & Stuart, E. A. (2011). Intervention targeting development of socially synchronous engagement in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(1), 13–21. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02288.x.

* Lang, R., Didden, R., Sigafoos, J., Rispoli, M., Regester, A., & Lancioni, G. E. (2009). Treatment of chronic skin-picking in an adolescent with Asperger syndrome and borderline intellectual disability. Clinical Case Studies, 8(4), 317–325. doi:10.1177/1534650109341841.

* Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Mogil, C., & Dillon, A. R. (2009). Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(4), 596–606. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0664-5.

* Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R., & Mogil, C. (2012). Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: The UCLA PEERS program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 1025–1036. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1339-1.

* Lawer, L., Brusilovskiy, E., Salzer, M. S., & Mandell, D. S. (2009). Use of vocational rehabilitative services among adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(3), 487–494. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0649-4.

Lawson, W. (2011). The passionate mind: How people with autism learn. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

* Leaf, J. B., Taubman, M., Bloomfield, S., Palos-Rafuse, L., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., & Oppenheim, M. L. (2009). Increasing social skills and pro-social behavior for three children diagnosed with autism through the use of a teaching package. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 275–289. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.07.003.

* Leaf, J. B., Oppenheim‐Leaf, M. L., Call, N. A., Sheldon, J. B., Sherman, J. A., Taubman, M., … & Leaf, R. (2012). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories for people with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 281–298. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-281.

* Lechago, S. A., Carr, J. E., Grow, L. L., Love, J. R., & Almason, S. M. (2010). Mands for information generalize across establishing operations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(3), 381–395. doi:10.1901/jaba.2010.43-381.

* Lequia, J., Machalicek, W., & Rispoli, M. J. (2012). Effects of activity schedules on challenging behavior exhibited in children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 480–492. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.008..

* Lerner, M. D., & Mikami, A. Y. (2012). A preliminary randomized controlled trial of two social skills interventions for youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. doi:10.1177/1088357612450613.

* Lerner, M. D., Mikami, A. Y., & Levine, K. (2010). Socio-dramatic affective-relational intervention for adolescents with Asperger syndrome & high functioning autism: Pilot study. Autism, 1–22. doi:10.1177/1362361309353613.

* Liber, D. B., Frea, W. D., & Symon, J. B. (2008). Using time-delay to improve social play skills with peers for children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(2), 312–323. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0395-z.

* Licciardello, C. C., Harchik, A. E., & Luiselli, J. K. (2008). Social skills intervention for children with autism during interactive play at a public elementary school. Education and Treatment of Children, 31(1), 27–37. doi:10.1353/etc.0.0010.

* Lopata, C., Thomeer, M. L., Volker, M. A., & Nida, R. E. (2006). Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral treatment on the social behaviors of children with Asperger disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 21(4), 237–244. doi:10.1177/10883576060210040501.

* Lopata, C., Thomeer, M. L., Volker, M. A., Nida, R. E., & Lee, G. K. (2008). Effectiveness of a manualized summer social treatment program for high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 890–904. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0460-7.

Lovaas, O. I. (1987). Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(1), 3–9. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.1.3.

* Lydon, H., Healy, O., & Leader, G. (2011). A comparison of video modeling and pivotal response training to teach pretend play skills to children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(2), 872–884. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.10.002.

* MacDonald, R., Clark, M., Garrigan, E., & Vangala, M. (2005). Using video modeling to teach pretend play to children with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 20(4), 225–238. doi:10.1002/bin.197.

* MacDonald, R., Sacramone, S., Mansfield, R., Wiltz, K., & Ahearn, W. H. (2009). Using video modeling to teach reciprocal pretend play to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(1), 43–55. doi:10.1901/jaba.2009.42-43.

* MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (1993). Teaching children with autism to use photographic activity schedules: Maintenance and generalization of complex response chains. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 89–97. doi:10.1901/jaba.1993.26-89.

* Machalicek, W., Shogren, K., Lang, R., Rispoli, M., O’Reilly, M. F., Franco, J. H., & Sigafoos, J. (2009). Increasing play and decreasing the challenging behavior of children with autism during recess with activity schedules and task correspondence training. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(2), 547–555. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.11.003.

* MacKay, T., Knott, F., & Dunlop, A. W. (2007). Developing social interaction and understanding in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A groupwork intervention. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 32(4), 279–290. doi:10.1080/13668250701689280

* Magiati, I., Charman, T., & Howlin, P. (2007). A two‐year prospective follow‐up study of community‐based early intensive behavioural intervention and specialist nursery provision for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(8), 803–812. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01756.x.

* Maione, L., & Mirenda, P. (2006). Effects of video modeling and video feedback on peer-directed social language skills of a child with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(2), 106–118. doi:10.1177/10983007060080020201.

* Marion, C., Martin, G. L., Yu, C. T., & Buhler, C. (2011). Teaching children with autism spectrum disorder to mand “What is it?”. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1584–1597. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.03.005.

* Mashal, N., & Kasirer, A. (2011). Thinking maps enhance metaphoric competence in children with autism and learning disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(6), 2045–2054. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.012.

* Massaro, D. W., & Bosseler, A. (2006). Read my lips: The importance of the face in a computer-animated tutor for vocabulary learning by children with autism. Autism, 10(5), 495–510. doi:10.1177/1362361306066599.

* Massey, N. G., & Wheeler, J. J. (2000). Acquisition and generalization of activity schedules and their effects on task engagement in a young child with autism in an inclusive pre-school classroom. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 326–335. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.lcproxy.shu.ac.uk/discover/10.2307/23879654?sid=21105442257931&uid=62&uid=3738032&uid=3&uid=67&uid=34516&uid=2&uid=34514&uid=5910784.

* McConachie, H., Randle, V., Hammal, D., & Le Couteur, A. (2005). A controlled trial of a training course for parents of children with suspected autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Pediatrics, 147(3), 335–340. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.056.

* McConachie, H., McLaughlin, E., Grahame, V., Taylor, H., Honey, E., Tavernor, L., … & Le Couteur, A. (2013). Group therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 1–10. doi:10.1177/1362361313488839.

* McDonald, M. E., & Hemmes, N. S. (2003). Increases in social initiation toward an adolescent with autism: Reciprocity effects. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 24(6), 453–465. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2003.04.001.

* McDonald, T. A., & Machalicek, W. (2013). Systematic review of intervention research with adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(11), 1439–1460. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2013.07.015.

* McDuffie, A. S., Yoder, P. J., & Stone, W. L. (2006). Labels increase attention to novel objects in children with autism and comprehension-matched children with typical development. Autism, 10(3), 288–301. doi:10.1177/1362361306063287.

McGregor, E., Núñez, M., Cebula, K., & Gómez, J. C. (2008). Autism: An integrated view from neurocognitive, clinical, and intervention research. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

* McMahon, C. M., Vismara, L. A., & Solomon, M. (2013). Measuring changes in social behavior during a social skills intervention for higher-functioning children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(8), 1843–1856. doi:10.1007/s10803

* Mechling, L. C., & Gustafson, M. R. (2008). Comparison of static picture and video prompting on the performance of cooking-related tasks by students with autism. Journal of Special Education Technology, 23(3), 31. Retrieved from http://am6ya8ud8k.scholar.serialssolutions.com.lcproxy.shu.ac.uk/?sid=google&auinit=LC&aulast=Mechling&atitle=Comparison+of+static+picture+and+video+prompting+on+the+performance+of+cooking-related+tasks+by+students+with+autism&title=Journal+of+special+education+technology&volume=23&issue=3&date=2008&spage=31&issn=0162-6434.

* Mechling, L. C., Pridgen, L. S., & Cronin, B. A. (2005). Computer-based video instruction to teach students with intellectual disabilities to verbally respond to questions and make purchases in fast food restaurants. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 47–59. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.lcproxy.shu.ac.uk/discover/10.2307/23879771?sid=21105442257931&uid=3738032&uid=34516&uid=5910784&uid=67&uid=62&uid=3&uid=2&uid=34514.

* Mechling, L. C., Gast, D. L., & Seid, N. H. (2009). Using a personal digital assistant to increase independent task completion by students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(10), 1420–1434. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0761-0.

Mesibov, G. B., & Shea, V. (2011). Evidence-based practices and autism. Autism, 15(1), 114–133. doi:10.1177/1362361309348070.

Mesibov, G. B., Shea, V., & Schopler, E. (with Adams, L., Burgess, S., Chapman, S. M., Merkler, E., Mosconi, M.,Tanner, C., & Van Bourgondien, M. E.). (2005). The TEACCH approach to autism spectrum disorders. New York: Springer.

* Miller, A., Vernon, T., Wu, V., & Russo, K. (2014). Social skill group interventions for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1(4), 254–265. doi:10.1007/s40489-014-0017-6.

* Minihan, A., Kinsella, W., & Honan, R. (2011). Social skills training for adolescents with Asperger’s syndrome using a consultation model. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(1), 55–69. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01176.x.

* Mitchel, K., Regehr, K., Reaume, J., & Feldman, M. (2010). Group social skills training for adolescents with Asperger Syndrome or high functioning autism. Journal on Developmental Disabilities. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2011-15965-006/

* Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135.

* Moore, T. R. (2009). A brief report on the effects of a self-management treatment package on stereotypic behavior. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(3), 695–701. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.01.010.

* Moore, M., & Calvert, S. (2000). Brief report: Vocabulary acquisition for children with autism: Teacher or computer instruction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(4), 359–362. doi:10.1023/A:1005535602064.