Abstract

Jealousy evokes strong psychological responses, but little is known about physiological effects. This study investigated whether actively thinking about a jealousy-provoking situation would result in a testosterone (T) response, and what factors might mediate this effect. We examined T responses to imagining one’s partner engaging in one of three activities: a neutral conversation with a co-worker, a flirtatious conversation with an attractive person, or a passionate kiss with an attractive person. Women in the flirting condition experienced a significantly larger increase in T relative to those in the neutral condition; the kissing condition was intermediate. In men, there were no significant effects of jealousy condition on T. These findings are consistent with the Steroid/Peptide Theory of Social Bonds, such that the flirting condition elicited a ‘competitive’ T response, and the kissing condition elicited responses consistent with defeat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Romantic jealousy is an emotion that arises when a person perceives that a valued relationship is under threat of being lost to another person (Holtzworth-Munroe et al. 1997; Puente and Cohen 2003), and such threats may be real or imagined (Rilling et al. 2004). Although jealousy can be experienced as a very serious and upsetting emotion (Pines and Friedman 1998; Sheets et al. 1997), it is commonly understood that jealous feelings can range from normal to pathological, and that those feelings can be manifested in ‘good’ or ‘bad’ ways (Conley et al. 2013; Daly et al. 1982). Given that jealousy encompasses a wide range of experiences, there is reason to suspect that not all types of jealousy are predicated upon the same psychological, affective, and physiological processes. Determining how these processes may be differentially evoked by different kinds of jealousy could be key to understanding jealousy and its functions in more detail.

An important distinction separates sexual jealousy from emotional jealousy (Guerrero et al. 2004). Sexual jealousy involves a threat to exclusive sexual access to a partner whereas emotional jealousy involves a threat to exclusive emotional access to a partner. For the purposes of this study, however, we examine relationships that are both emotional and sexual and thus jealousy that can contain both types; one of many important future questions would be to experimentally test each one separately.

Testosterone, Competition, and Romantic Jealousy

Testosterone (T) is a steroid hormone that has been associated with sexuality and competition (Hamilton et al. 2009; Mehta et al. 2009; van Anders 2013; Wingfield et al. 1990). Although T is positively linked with many aspects of sexual contexts (Goldey and van Anders 2011; van Anders 2013), associations are more nuanced than largely assumed, with pleasure-focused sexuality especially salient for increasing T in women (van Anders and Goldey 2010; van Anders et al. 2011; van Anders 2013). In addition to some sexual contexts, competitive situations—which are defined as those that involve the acquisition or defense of resources (e.g., food, territory, or erotic opportunities; van Anders et al. 2011)—have also been shown to increase T (Carre and McCormick 2008; Hirschenhauser and Oliveira 2006; van Anders and Watson 2006). Effects of competition on T have been generally investigated within athletic contexts and/or using only men as participants, but competition is also relevant to romantic relationships for both men and women. These relationships can involve maintaining partners over time despite the presence of rivals (VanderLaan and Vasey 2008). The current study examines whether relationship-based competitions, which could invoke jealousy, are associated with T as well.

Romantic jealousy might include several socially relevant components, including competition, aggression, and/or intimacy. Given T’s important role in social bonding and aggression processes, there is reason to believe that changes in T may be an important pathway through which individuals generate behavioral responses to social stimuli. The Steroid-Peptide Theory of Social Bonds (S/P Theory) identifies two types of aggression (antagonistic and protective) and two types of intimacy (erotic and nurturant) that have different effects on T and peptides (van Anders et al. 2011). Given the multifaceted nature of jealousy, it may evoke some physiological responses relevant to aggression and competition, and other responses consistent with intimacy and bonding. The S/P Theory is useful for theorizing how jealousy might affect T: e.g., is it an aggressive feeling? A competitive one? A hurt one? A loss of intimacy, or a feeling of increased closeness to a partner whose value is made salient by attention from a rival?

Hormonal correlates of jealousy are not widely studied, but the involvement of T in pair bonding suggests that it may be implicated in romantic jealousy as well. Furthermore, experiencing jealousy may be analogous to experiencing rivalry and competition in other contexts (e.g., athletic competitions). Accordingly, we hypothesize that romantic jealousy will increase T. However, competitions have been shown to have mixed effects on T, in part depending on competition outcome. Some evidence points to competition losses, or defeats, as decreasing T (Archer 2006). And, different perceptions of the same context may lead to different hormonal changes (van Anders et al. 2011). Accordingly, we expect that the effects of jealousy on T may differ depending on perceived ‘outcome’ of the situation and will also depend on the individual’s perception of the event.

The context-dependence of jealousy can include a variety of factors. These factors may modulate T responses. These factors also may modulate the outcomes of jealousy, given that jealousy can lead to a range of behavioral responses including upregulating relationship effort or increasing motivations for perpetrating violence (Daly et al. 1982; Puente and Cohen 2003; Tarrier et al. 1990). Characterizing the role these factors play in hormonal and behavioral responses to jealousy can provide new insights into the antecedents and sequelae of jealousy. Important factors might include individual and experiential/context characteristics, described further below.

Individual Characteristics

Individual characteristics that may be related to the experience of jealousy include personality, attachment style, and gender/sex. These individual variables may influence the way jealousy is experienced, or even whether a given context elicits jealousy. And, these factors could be relevant to the ways in which jealousy affects T via perceptual mechanisms.

Studies have shown that jealousy is positively correlated with neuroticism among the big-five personality traits (Dijkstra and Barelds 2008; Melamed 1991). This is not surprising given that jealousy can elicit feelings of insecurity when a partner is perceived to be distant and can lead to feelings of security when a partner is perceived to be close (Hazan and Shaver 1987; Sheets et al. 1997). Responses to jealousy also appear to differ depending on an individual’s attachment style (Fisher et al. 2013), and may be especially strong for individuals who have attachment styles characterized by high levels of anxiety and/or who consider romantic and sexual exclusivity to be very important. We hypothesize that neuroticism and attachment style will be related to jealous experiences, and that controlling for these individual differences may elucidate an effect of jealousy on testosterone.

Sex typically refers to biological maleness or femaleness, and gender is often used to refer to socially constructed notions of what constitutes women and men. We use the term gender/sex to highlight the interconnectedness of biological sex and social constructions of gender (van Anders et al. 2014). Although studies have shown that there are no gender differences in the frequency and intensity of jealous feelings (Shackelford et al. 2000), the interpretation and expression of jealousy may differ by gender/sex. For example, in response to a partner’s infidelity, some studies suggest that men experience anger more frequently than do women (Becker et al. 2004; Pietrzak et al. 2002; Sabini and Green 2004). However, research has also shown that gender/sex differences do not emerge for hurt or disgust-related responses in response to hypothetical infidelity (Becker et al. 2004). These findings are highly variable across studies, suggesting that gender/sex differences are either complex or do not exist with regard to jealousy (Harris 2005). Gender differences are also nuanced and highly dependent on the type of measurement. For example, though women are more likely to say they would end a relationship following a hypothetical affair, men are more likely to actually have done so in real life (Confer and Cloud 2011). Thus, though there are gender/sex differences in the elicitation of jealousy, individuals of any gender/sex are capable of exhibiting jealousy in response to various types of rivals and differences may be overstated (Harris 2002, 2003). Most importantly, a strong focus on gender/sex differences may obscure a more nuanced understanding of the physiological processes that might underlie jealousy for individuals of any gender/sex. Because the current study considers committed relationships that involve both emotional and sexual components, we do not expect any gender differences in the amount of emotional or sexual jealousy experienced. However, due to gender/sex differences in the baseline levels and function of T, we expect that jealousy may differentially impact T in men and women. Prior findings suggest that the social modulation of T occurs differently for women and men, with sexual contexts altering T more for women and nurturant contexts altering T more for men (van Anders 2013).

Experiential and Contextual Factors

In addition to the individual factors described above, the experience of jealousy may be influenced by situational factors, including experience with infidelity and relationship agreements. Studies have found that, when exposed to a hypothetical situation of partner infidelity, individuals who have never been unfaithful in real life are more likely than those who have been unfaithful to say they would end the relationship (Confer and Cloud 2011). These authors proposed that being unfaithful might increase empathy toward partners who do the same, or displaying understanding toward an unfaithful partner enables people to excuse their own prior actions. We expect that having experienced past partner infidelity would alter the way that individuals experiences jealousy in their current relationship; therefore, we hypothesize that controlling for past partner infidelity may reveal an effect of the jealousy-provoking vignettes on T. Exclusive sexual access to a partner is important to many people (Sharpsteen and Kirkpatrick 1997), though some (e.g., polyamorous individuals) may feel otherwise. Polyamorous people do feel jealousy, but generally find it more manageable than monoamorous people (de Visser and McDonald 2007). Jealousy, therefore, may be experienced differently by people in monoamorous vs. polyamorous relationships.

The Current Study

This study investigated whether actively thinking about a situation designed to provoke jealousy modulates T in partnered individuals and what factors might mediate this effect. We focused on partnered individuals because there is good reason to expect that romantic jealousy would be more salient for those in current relationships than it would for single people. Because the field has few methods for executing a controlled study that elicits jealousy in the laboratory without raising ethical concerns (Harris 2003), we modified an existing experimental manipulation already validated for romantic and sexual situations (i.e., the Imagined Social Situation Exercise, ISSE; Goldey and van Anders 2011). Expanding upon previous methods that simply ask participants how upsetting certain types of infidelity would be, we asked participants to imagine themselves in the situation by reading a descriptive vignette and thinking about themselves immersed in the situation. We compared changes in T resulting from imagining one’s partner engaging in one of three activities: a neutral conversation with a co-worker, a flirtatious conversation with an attractive person, or a passionate kiss with an attractive person. Based on past research and the S/P Theory, we hypothesized that the conditions designed to provoke jealousy would increase T compared to those in the neutral condition, and that the T levels of those in the kissing condition would increase more than those in the flirting condition due to the intensity of jealousy-provocation. We also expected that contextual factors (i.e., experience with infidelity and relationship agreements for monogamy vs. polyamory) would influence these outcomes.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 168) were 103 women (M age = 20.36 years, SD = 3.86) and 65 men (M age = 20.25 years, SD = 2.72) who were in committed romantic relationships. The majority of participants had one relationship partner, though some participants reported having two (n = 2) three (n = 2) or six or more partners (n = 1). Participants were recruited from the undergraduate psychology subject pool and from the community through online advertisements and posters, and were compensated with course credit or $15 as appropriate. Though the majority were students (n = 153), many were employed (n = 58), and there was a broad representation of occupations. All participants had graduated from high school, and most (n = 108) had some college experience. Participants self-identified their race/ethnicity and we categorized their responses such that participants were: 10 African American/Black, 31 Asian/Asian American, six Bi/Multiracial, 98 Caucasian/White, one Chinese-American, three European, seven Hispanic/Latino/a, three Indian, and four Middle Eastern/Southeast Asian individuals. One participant gave a response that could not be categorized (“American”) and four participants did not report race/ethnicity. Participants self-identified their sexual orientation/identity, which we categorized as bisexual (n = 5), gay or lesbian (n = 5), and heterosexual (n = 148); five participants gave responses that did not fit into these categories (i.e., “male”), and five did not report sexual orientation. Though the majority of participants lived in the U.S. for their entire lives (n = 133), some lived in the U.S. for 11–21 years (n = 14), and others for 10 years or less (n = 19). Nine participants were excluded from analyses involving hormones because they reported taking hormonal contraceptives (n = 8) or reported having testicular surgery (n = 1).

Materials

Relationship and Partner Questionnaire

This 10-item questionnaire included past and present relationship information. Since eligibility criteria for this study indicated that participants had to be in committed relationships, this questionnaire was designed for partnered individuals. Participants with multiple partners were instructed to answer based on their choice of either (a) the partner to whom they felt most committed, or (b) the partner with whom they had been the longest. Questionnaire items requested information about current relationship length, frequency of sexual activity, and satisfaction of sexual activity with partner. One item asked participants about the discrepancy that they believe others perceive between their partner’s and their own attractiveness on a seven-point scale between “People think I am more attractive than my partner” and “People think my partner is more attractive than me.” Assessing self-rated quality relative to one’s partner allowed us to control for differences in partner quality.

Quality Marriage Index (QMI; Norton 1983)

This index contained five brief statements regarding the overall quality of the participant’s relationship. Since this index was originally designed for married individuals, we adapted the instructions and statements for people who are partnered but not necessarily married, as we and others have done successfully in the past. Participants indicated how accurately each statement described their relationship on a seven-point scale ranging from “1” = “Very strong disagreement” to “7” = “Very strong agreement.” Finally, the index asked participants to rate their relationship on a scale from “1” = “Very unhappy” to “7” = “Very happy.” We measured relationship satisfaction because those in satisfying relationships may experience jealousy differently than those in unsatisfying relationships.

Affect and Arousal Scale (AAS; Heiman and Rowland 1983)

This scale is used to measure levels of physical, psychological, and sexual arousal. It was administered prior to the experimental manipulation (time 1), immediately following the manipulation (time 2), and fifteen minutes after the manipulation (time 3) in order to measure changes in arousal between these three time points. We removed items pertaining to sexual arousal and added the following items relevant to the present study to assess emotions that had high face validity for being associated with jealousy: “a desire to be close to a friend,” “a desire to be close to my partner,” “sad,” “happy,” “stressed,” “relaxed,” “jealous,” “annoyed,” “apathetic (do not care),” “curious,” “disappointed,” “fearful,” “hostile,” “frustrated,” “lonely,” “surprised,” “betrayed,” “hurt,” “ashamed,” “humiliated,” and “violent.” An altered version of the AAS has been used successfully in a similar study (Goldey and van Anders 2011).

Participants indicated how accurately each statement described their current feelings on a seven-point scale ranging from “1” = “Not at all” to “7” = “Intensely.” The version used for this study contained a total of 46 items, which resolved via factor analysis into 11 subscales: hurt feelings (e.g., “betrayed”), negative self-conscious affect (e.g., “incompetent”), positive affect (e.g., “excited”), intimacy (e.g., “a desire to be close to my partner”), sexual feelings (e.g., “sexually aroused”), shame (e.g., “humiliated”), autonomic arousal (e.g., “faster breathing than normal”), anxious arousal (e.g., “worried”), loneliness (e.g., “a desire to be close to a friend”), deactivation (e.g., “apathetic”), and hostility (“violent”). We omitted four items that did not conceptually fit well into any of the subscales (“curious,” “surprised,” “masculine,” and “feminine”). We measured arousal and certain types of affect to assess affective responses to reading the vignettes.

Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR; Brennan et al. 1998)

We used this measure to assess anxious or avoidant romantic attachment style. It included measures of anxiety (e.g., “I do not often worry about being abandoned”) and avoidance (e.g., “I am nervous when partners get too close to me”), which form the categories of attachment style. For this study, a 12-item, shortened version was used. Participants indicated their agreement with each item on a seven-point scale ranging from “1” = “Disagree strongly” to “7” = “Agree strongly.” We measured attachment style because it has been associated with jealousy in other studies.

Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10; Rammstedt and John 2007)

The 10-item version of the Big Five Inventory was used to measure personality in the Big Five domains of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Participants indicated their agreement with each item on a five-point scale ranging from “1” = “Disagree strongly” to “5” = “Agree strongly.” We measured personality because previous studies linked neuroticism with increased jealousy (Dijkstra and Barelds 2008; Melamed 1991).

Experimental Vignettes

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: neutral, flirting, or kissing. In each of the three conditions, participants read about and imagined themselves in a social situation involving their current partner. The vignettes were a jealousy version of the Imagined Social Situation Exercise (Goldey and van Anders 2011). Each of the vignettes used parallel language, keeping the scenarios constant across conditions except for intentional manipulation (see Appendix for full texts of each condition’s prompts). Pronouns were altered to match the gender/sex of each participant’s current partner. In the neutral condition, the partner is seen speaking with a colleague about a boring work project. The partner and the colleague do not touch while talking. In the flirting condition, the partner is seen speaking and laughing with an attractive person. The attractive person rests their hand on the partner’s arm while talking. In the kissing condition, the partner is seen kissing an attractive person passionately in an upstairs room. Participants also responded to an open-ended directed set of questions about their feelings and actions in response to these scenarios; this qualitative data is not included in this paper.

Relationship, Infidelity, and Extra-Dyadic Sexuality Questionnaire

The first item of this questionnaire asked whether the participant had sexual contact outside of their current relationship without their partner’s approval. The second and third items asked whether the participant’s current or past partners have had such sexual contact. Those who responded affirmatively to any of these three questions were then asked follow-up questions related to the type, context, and duration of the sexual contact(s). For questions related to partner infidelity, participants may not have known the details of the encounters, so they were instructed to answer to the best of their knowledge.

Health and Background Questionnaire

This questionnaire asked about demographic information and possible saliva sample confounds such as eating, drinking, smoking cigarettes, chewing gum, and taking hormonal contraceptives.

Procedure

This study was approved by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board. Testing occurred between 11:00 and 19:00 h in order to avoid peaks in steroid hormones that occur in the morning and/or upon waking (van Anders et al. 2014). Participants were tested between September and November. One study found that fluctuations in T across menstrual cycle are even smaller than daily fluctuations or individual differences in T (Dabbs and de La Rue 1991), and research has repeatedly shown that menstrual phase need not be controlled for in T analyses unless it is of special interest (for a summary, see van Anders et al. 2014). Because menstrual phase was not specifically of interest in the current study, we tested women at any phase. Researchers asked participants to refrain from eating, drinking, smoking, brushing their teeth, or chewing gum for one hour prior to their appointment.

Upon arrival, participants were provided with a consent form, which they read and signed in agreement to participate. They provided a baseline saliva sample (T1) while filling out the first set of questionnaires, which included the relationship and partner questionnaire, the QMI, the AAS, the ECR, the BFI-10, and some other potentially relevant measures. Participants then read one of three hypothetical vignettes involving their relationship partner and imagined themselves in the situation. Next, they completed the open-ended questions and the AAS. Participants then watched a 12-minute travel video to occupy time, since the social modulation of T is delayed (van Anders et al. 2014). Next, participants completed a second saliva sample (T2) while filling out the second set of questionnaires, which included the AAS, the relationship, infidelity, and extra-dyadic sexuality questionnaire, and the health and background questionnaire.

Due to the sensitive nature of the study, participants in the flirting and kissing conditions were verbally debriefed in addition to receiving a printed copy of the debriefing form. A researcher explained to each participant that the situations they were asked to imagine may have been upsetting and may have led to strong emotions, but highlighted their artificial nature. These participants were asked to answer a short survey that encouraged them to focus on positive aspects of their relationship. This helped to refocus participants to the positive aspects of their actual relationships. Physical and mental health resources were provided in the debriefing form, which was provided to participants in all conditions, and participants were encouraged to ask any questions they had about the study. They were then compensated with course credit or $15 as appropriate.

Assays

T was measured via saliva, which was collected via passive drool into 17-mL polystyrene tubes. Immediately following collections, samples were frozen and stored at −20 °C until assay. Radioimmunoassays were performed at the Core Assay Facility, University of Michigan, using commercially available kits from Siemens. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 10.56 % and the inter-assay coefficients were 4.98, 7.41, and 23.22 % for high, medium, and low T, respectively. Assays were performed in duplicate, and the average of duplicates was used for analyses. This method has been validated (van Anders et al. 2014).

Analyses

Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0. Since we were interested in changes from baseline to post-condition, we calculated percent change in T (T%) by subtracting participants’ baseline hormone (T1) from post-condition hormone (T2), dividing this change by baseline level, and multiplying by 100. This provided a change measure of T relative to participants’ own baseline levels. Percent change scores are more sensitive than absolute changes due to large between-subjects variability in baseline hormone levels and receptor densities, and thus have been used to more meaningfully analyze hormone changes from baseline (for a review, see van Anders et al. 2014). Because T levels differ by gender/sex, we conducted analyses separately for men and women, as is standard practice (van Anders et al. 2014).

We conducted analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) to investigate the effects of condition on T%, with covariates as indicated below. When there were significant effects, we conducted post hoc analyses using LSD tests.

To capture changes in affect and arousal, we administered the AAS at three different time points and conducted correlations using time 2 minus time 1 and time 3 minus time 1; we used both because it was unclear whether changes at time 2 (immediately post-manipulation) or time 3 (at hormone sampling) would be more strongly implicated. We were interested in whether changes in affect and arousal were similar or different between the three conditions. To test this, we conducted an a multivariate ANOVA with condition as the independent variable and absolute change scores of the AAS subscales as the dependent variables. In order to examine whether changes in T were correlated with changes in affect and arousal, we conducted Pearson correlations between T% and absolute changes in subscales of the AAS within the two experimental conditions.

Participants spent an average of 27.83 s reading and imagining the situations (SD = 15.30), with no significant differences between conditions, F(2,165) = 0.60, p = .55.

We excluded outliers (more than 3 SDs from the mean or a visual outlier) from analyses involving hormones. There were two outliers for T1, one for T2 (who was also an outlier for T1), and nine for T%. Due to procedural interruptions, two participants were not able to provide saliva samples, and therefore do not have hormone data available for analysis. Possible confound variables for T include age, time of day, BMI, and nicotine use (for a review, see van Anders et al. 2014). However, we found that none of these were meaningful or significant covariates with T for men or women.

Results

Effects of Condition on T% and Affect

Women

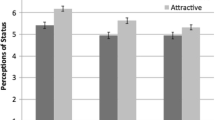

In women, a univariate ANOVA with condition as the independent variable and T% as the dependent variable revealed no significant effects of condition on T, F(2,84) = 1.93, p = .152. However, controlling for both past partner infidelity and neuroticism in an ANCOVA revealed a significant overall effect of condition on T, F(2,79) = 3.27, p = .043 (see Fig. 1). Post-hoc tests indicated that T% was significantly greater in the flirting condition compared to the neutral condition (p = .01). There were no significant differences in T% between the kissing and flirting conditions (p = .11) or the kissing and neutral conditions (p = .29). None of the other potentially important factors we measured affected the pattern of results (relationship length, self infidelity, current partner infidelity, relationship quality, attachment, self-rated attractiveness relative to partner, and relationship agreement).

Because women’s T increased in the flirting but not the kissing condition, we examined whether changes in affect differed between the three conditions. There was an overall difference, and post hoc tests revealed that, compared to women in the neutral and flirting conditions, those in the kissing condition experienced significantly more hurt feelings, more shame, more autonomic arousal, and less positive affect throughout the course of the experimental manipulation, all ps < .05. There was also a trend for changes in intimacy to differ across conditions (p = .08), and post hoc tests revealed that women in the kissing condition experienced a larger decrease in intimacy than those in the neutral condition (p = .03).

Men

In men, there was no significant effect of condition on T%, F(2,55) = 1.88, p = .163; however, men in the kissing condition experienced a nonsignificant decrease in T relative to the other two conditions (see Fig. 2). Based on our findings in women, we added past partner infidelity and neuroticism as covariates, but this did not change the pattern of results. The inclusion of other potentially important factors also did not affect the pattern of null results. An independent samples t-test revealed a trend for T% to differ between the flirting (M = 8.83; SD = 17.20) and kissing (M = −0.58; SD = 15.10) conditions, p = .094, though given the post hoc analysis, the result could reflect increased error.

Men in the flirting condition experienced a significantly larger decrease in intimacy than men in the kissing condition, t(41) = 2.09, p = .043, and there was a trend for men in the kissing condition to experience a larger increase in hostility than men in the flirting condition, t(41) = =1.74, p = .089. There were no other significant changes on the AAS.

Correlations Between T% and Affect and Arousal (AAS)

Women

We conducted correlations between T and AAS scores separately for the flirting and kissing conditions, given that they differentially affected T. For women in the flirting condition, T% was significantly positively correlated with the absolute change in intimacy from time 1 to time 2, partial r(23) = .437, p = .029, and from time 1 to time 3, partial r(23) = .471, p = .017. In contrast, T% and intimacy were not significantly correlated in the kissing condition from time 1 to time 2, partial r(26) = . 126, p = . 523, or from time 1 to time 3, partial r(26) = .230, p = . 238. Since T% was not significantly correlated with any other subscales of the AAS, it is possible that the correlations with intimacy arose due to type I error.

Men

For men in the flirting and kissing conditions, T% was not significantly correlated with any subscales of the AAS.

Covariates

For all correlations, we attempted to control for variables that might affect hormones including age, BMI, and nicotine use, but this did not change the pattern of effects. We also controlled for variables that served as covariates in prior analyses, but doing so did not change the pattern of results.

Discussion

In this experiment, we examined the effects of jealousy-provoking situations on testosterone (T). To do so, we used a version of the ISSE (Goldey and van Anders 2011), where participants imagined themselves in one of three situations involving their partner, two of which were intended to elicit jealousy and one of which was a control.

In women, results partially supported our first hypothesis: flirting significantly increased T compared to the neutral condition. Results did not support our second hypothesis: kissing did not increase T more than flirting did and, moreover, it did not significantly increase T at all relative to the neutral condition. We found that neuroticism, which has been linked to jealousy in the past (Dijkstra and Barelds 2008; Melamed 1991), was a significant covariate in effects of jealousy on T. Past partner infidelity was also a meaningful covariate, which was not surprising given that prior infidelity experiences could impact the way individuals experience jealousy and trust (Buunk 1995; Confer and Cloud 2011). Our research thus showed that imagining one’s partner flirting with an attractive person increases T in women, and that neuroticism and partner infidelity help to clarify this effect. In contrast to the findings with women, we found no significant effects of jealousy on T in men, which mirrors past research showing sexual modulation of T in women but not men (van Anders 2013).

Why did flirting but not kissing change T in women? One possibility is that extradyadic flirting leads an individual to believe that a rival is threatening the relationship. Threats to relationships could be conceptualized as ‘competitive,' which involve acquiring or defending ‘resources’ including partners, as per the Steroid/Peptide Theory of Social Bonds (S/P Theory; van Anders and Goldey 2012). Competitive contexts have been empirically shown and theorized to increase T (Carre and McCormick 2008; Hirschenhauser and Oliveira 2006; Mehta et al. 2009; van Anders and Watson 2006; Wingfield et al. 1990). Flirting might thus cue a competitive androgen response.

In contrast, finding one’s partner kissing another person might be more akin to a defeat, where a rival has already ‘won.’ In such a case, the individual may respond as though they have lost a competition, with a decrease in T relative to the change in T elicited from the challenge condition (i.e., one may see a decrease in T, an ameliorated increase in T, or a lack of increase in T; e.g., van Anders and Watson 2006). We found that the kissing condition elicited stronger negative emotions than the neutral and flirting conditions, which might help to explain why T responses differed between them, given that those negative emotions are related to defeat and loss (e.g., hurt feelings, shame). In addition, women in the kissing condition experienced a larger decrease in positive affect than those in the neutral and flirting conditions, suggesting that the kissing condition was serious enough to suppress mood in a way that the other two conditions did not, supporting the ‘kissing as defeat’ interpretation. Thus, even though kissing and flirting both elicit jealousy, they elicit different kinds of jealousy that, accordingly, affect T in different ways.

Why did women, but not men, show effects of jealousy on T? Both women and men experienced affective changes in response to the conditions, so the lack of T response cannot be explained by this. Experimental studies about nurturance, which predict a decrease in T, tend to find decreases in men but not women (van Anders et al. 2012), and studies about sexuality, which predict an increase in T, find increases in women but not men (Goldey and van Anders 2011). This might be due to the differences in baseline T in women (lower) and men (higher), such that it is more difficult to decrease T in women than in men, and easier to increase T in women than in men.

We considered that there may not have been an effect in men due to their T responses being more variable than women’s, but this was not the case as men’s T responses were not significantly more variable; in fact, women’s were more variable (F = 10.72, p = .001), though there was still a range of responses in men. Though a nonsignificant trend, T% was lower in the kissing condition than the flirting and neutral conditions in men; thus, it may be possible that the experience of ‘defeat’ that accompanied imagining one’s partner kissing another person decreases testosterone in men. Although jealousy is often presumed to be a negative emotion with harmful consequences, the findings from this study suggest that jealousy-provoking situations are not uniform. The vignettes in the flirting and kissing conditions were both designed to elicit jealousy, but it is clear that there are important differences in their effect on T. Moreover, they elicited very different affective responses with the kissing condition characterized by less positive affect and more hurt feelings, shame, and autonomic arousal compared to the flirting condition. This supports our post hoc interpretation that viewing one’s partner kissing another person did not increase T because it involves defeat-like affect rather than competition-like feelings as per viewing the flirting.

For women, increases in T were associated with increases in feelings of intimacy in both experimental conditions, and especially in the flirting condition. This is surprising, given that high levels of T tend to be associated with low levels of intimacy based on the Challenge Hypothesis (Wingfield et al. 1990). However, S/P Theory suggests that intimacy should be separated into two types: erotic intimacy, associated with increased T, and nurturant intimacy, associated with decreased T (van Anders et al. 2011; van Anders 2013). The AAS measure unfortunately did not differentiate between the two, but if the increased ‘intimacy’ that participants felt was more erotic than nurturant, this finding would make sense. In fact, this appears to be the case, as the intimacy category includes, “loving,” “a desire to be close to my partner,” and “a desire for sexual activity with a partner.”

The lack of other associations between T% and items in the AAS was not surprising given that prior studies have shown that self-reported affect tends not to be strongly associated with changes in hormones (Goldey and van Anders 2011; van Anders et al. 2007). This may be because changes in hormones are not actually linked to affect at all, or may be because changes in hormones and self-reported affect do not occur during the time points at which they have been measured in the past. We tested the second possibility in this study via a methodologically important manipulation whereby we measured affect and arousal at three time points: pre-manipulation (time 1), post-manipulation (time 2), and 15 min post-manipulation (time 3). This design allowed us to test changes from pre- to post-manipulation, as well as changes from pre- to 15 min post-manipulation, allowing us to determine whether affect is linked to jealousy and/or T% changes with some delay of time. The degree of association between T% and change in intimacy was similar at time 2 and time 3, suggesting that if changes in T are associated with changes in feelings of intimacy, the association remains for at least 15-minutes post-manipulation. Alternatively, it may be that the correlation between T% and intimacy arose due to inflated error rate. Future replications will clarify this. Given that we found significant differences in changes in affect between conditions at time 2 but not time 3, it appears that the three situations elicited different changes in affect and arousal, but that these differences did not persist at the 15-minute post-manipulation time point.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated an increase in T in women upon imagining their partners engaging in extradyadic flirting compared to neutral extradyadic encounters, in ways supported by the S/P Theory (van Anders and Goldey 2012). The affective and neuroendocrine differences between the flirting and kissing conditions suggest that jealousy might represent a type of competition in which an individual either attempts to maintain exclusive access to their partner or realizes that such access has been violated and perceives the extradyadic encounter as a loss. This opens up questions about jealousy and its multifaceted nature; e.g., are all types of jealousy comparable to competition? Do people consciously perceive jealousy-provoking situations as competition to maintain exclusive access to a partner? How might age or lifephase moderate effects of jealousy on T? Although this study’s mostly young and monoamorous sample is useful as a starting point, there is a need for studies to consider jealousy in older populations and across different types of relationship configurations. The current study employed an imagined situation method that avoided the need to provoke jealousy in real life, which is helpful for studying jealousy in many types of populations using lab-based experimental techniques. Results of this study demonstrate that this model is useful for discovering hormonal effects of romantic jealousy, and for identifying subtypes of jealousy-provoking situations that may have different biological and emotional associations.

References

Archer, J. (2006). Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 30, 319–345.

Becker, D. V., Sagarin, B. J., Guadagno, R. E., Millevoi, A., & Nicastle, L. D. (2004). When the sexes need not differ: emotional responses to the sexual and emotional aspects of infidelity. Personal Relationships, 11, 529–538.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment. In J. Simpson & W. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York: The Guilford Press.

Buunk, B. P. (1995). Sex, self-esteem, dependency and extradyadic sexual experience as related to jealousy responses. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 147–153.

Carre, J. M., & McCormick, C. M. (2008). In your face: facial metrics predict aggressive behaviour in the laboratory and in varsity and professional hockey players. Proceedings of the Royal Society, 275(1651), 2651–2656.

Confer, J. C., & Cloud, M. D. (2011). Sex differences in response to imagining a partner’s heterosexual or homosexual affair. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 129–134.

Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J., & Valentine, B. (2013). A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17, 124–141.

Dabbs, J. M., & de La Rue, D. (1991). Salivary testosterone measurements among women: relative magnitude of circadian and menstrual cycles. Hormone Research, 35, 182–184.

Daly, M., Wilson, M., & Weghorst, S. J. (1982). Male sexual jealousy. Ethology and Sociobiology, 3, 11–27.

de Visser, R., & McDonald, D. (2007). Swings and roundabouts: management of jealousy in heterosexual ‘swinging’couples. British Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 459–476.

Dijkstra, P., & Barelds, D. P. H. (2008). Self and partner personality and responses to relationship threats. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1500–1511.

Fisher, M., Edelstein, R., Chopik, W., Fitzgerald, C., & Strout, S. (2013). Was that cheating? Perceptions vary by sex, attachment anxiety, and behavior. Evolutionary Psychology, 11(1), 159–171.

Goldey, K. L., & van Anders, S. M. (2011). Sexy thoughts: effects of sexual cognitions on testosterone, cortisol, and arousal in women. Hormones and Behavior, 59, 754–764.

Guerrero, L. K., Spitzberg, B. H., & Yoshimura, S. M. (2004). Sexual and emotional jealousy. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 311–345). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hamilton, L. D., van Anders, S. M., Cox, D. N., & Watson, N. V. (2009). The effect of competition on salivary testosterone in elite female athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 4, 538–542.

Harris, C. R. (2002). Sexual and romantic jealousy in heterosexual and homosexual adults. Psychological Science, 13, 7–12.

Harris, C. R. (2003). A review of sex differences in sexual jealousy, including self-report data, psychophysiological responses, interpersonal violence, and morbid jealousy. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 102–128.

Harris, C. R. (2005). Male and female jealousy, still more similar than different: reply to Sagarin. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9, 76–86.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. 52, 511–524.

Heiman, J. R., & Rowland, D. L. (1983). Affective and physiological sexual response patterns: the effects of instructions on sexually functional and dysfunctional men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 27, 105–116.

Hirschenhauser, K., & Oliveira, R. (2006). Social modulation of androgens in male vertebrates: meta-analyses of the challenge hypothesis. Animal Behaviour, 71, 265–277.

Holtzworth-Munroe, A., Stuart, G. L., & Hutchinson, G. (1997). Violent versus nonviolent husbands: differences in attachment patterns, dependency, and jealousy. Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 314.

Mehta, P. H., Wuehrmann, E. V., & Josephs, R. A. (2009). When are low testosterone levels advantageous? The moderating role of individual versus intergroup competition. Hormones and Behavior, 56, 158–162.

Melamed, T. (1991). Individual-differences in romantic jealousy - the moderating effect of relationship characteristics. European Journal of Social Psychology, 21, 455–461.

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: a critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and Family, 45, 141–151.

Pietrzak, R. H., Laird, J. D., Stevens, D. A., & Thompson, N. S. (2002). Sex differences in human jealousy - a coordinated study of forced-choice, continuous rating-scale, and physiological responses on the same subjects. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 83–94.

Pines, A. M., & Friedman, A. (1998). Gender differences in romantic jealousy. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138, 54–71.

Puente, S., & Cohen, D. (2003). Jealousy and the meaning (or nonmeaning) of violence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 449.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 203–212.

Rilling, J. K., Winslow, J. T., & Kilts, C. D. (2004). The neural correlates of mate competition in dominant male rhesus macaques. Biological Psychiatry, 56, 364–375.

Sabini, J., & Green, M. C. (2004). Emotional responses to sexual and emotional infidelity: constants and differences across genders, samples, and methods. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1375–1388.

Shackelford, T. K., LeBlanc, G. J., & Drass, E. (2000). Emotional reactions to infidelity. Cognition & Emotion, 14, 643–659.

Sharpsteen, D. J., & Kirkpatrick, L. A. (1997). Romantic jealousy and adult romantic attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 627–640.

Sheets, V. L., Fredendall, L. L., & Claypool, H. M. (1997). Jealousy evocation, partner reassurance, and relationship stability: an exploration of the potential benefits of jealousy. Evolution and Human Behavior, 18, 387–402.

Tarrier, N., Beckett, R., Harwood, S., & Bishay, N. (1990). Morbid jealousy - a review and cognitive-behavioral formulation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 319–326.

van Anders, S. M. (2013). Beyond masculinity: testosterone, gender/sex, and human social behavior in a comparative context. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology.

van Anders, S. M., & Goldey, K. L. (2010). Testosterone and partnering are linked via relationship status for women and ‘relationship orientation’ for men. Hormones and Behavior, 58, 820–826.

van Anders, S. M., & Goldey, K. L. (2012). The steroid/peptide theory of social bonds: a reply to Goodson’s letter to the editor. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37, 445.

van Anders, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2006). Social neuroendocrinology: effects of social contexts and behaviors on sex steroids in humans. Human Nature, 17, 212–237.

van Anders, S. M., Hamilton, L. D., & Watson, N. V. (2007). Multiple partners are associated with higher testosterone in North American men and women. Hormones and Behavior, 51, 454–459.

van Anders, S. M., Goldey, K. L., & Kuo, P. X. (2011). The steroid/peptide theory of social bonds: integrating testosterone and peptide responses for classifying social behavioral contexts. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36, 1265–1275.

van Anders, S. M., Tolman, R. M., & Volling, B. L. (2012). Baby cries and nurturance affect testosterone in men. Hormones and Behavior, 61, 31–36.

van Anders, S. M., Goldey, K. L., & Bell, S. N. (2014). Measurement of testosterone in human sexuality research: methodological considerations. Archives of Sexual Behavior.

VanderLaan, D. P., & Vasey, P. L. (2008). Mate retention behavior of men and women in heterosexual and homosexual relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 572–585.

Wingfield, J. C., Hegner, R. E., Dufty, A. M., & Ball, G. F. (1990). The challenge hypothesis - theoretical implications for patterns of testosterone secretion, mating systems, and breeding strategies. American Naturalist, 136, 829–846.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ritchie, L.L., van Anders, S.M. There’s Jealousy…and Then There’s Jealousy: Differential Effects of Jealousy on Testosterone. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 1, 231–246 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-015-0023-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-015-0023-7