Abstract

The recent global economic crisis and pandemic have shown that housing markets are highly exposed to the prevailing economic and social circumstances. Relevant literature indicates that housing output and transaction volumes were negatively affected during the Covid-19 pandemic. In contrast, price levels displayed variations under different circumstances shaped by demand shifts. Housing affordability conditions also deteriorated and household budgets were squeezed by the high housing cost burden due to the loss of livelihood and increased time spent at home during lockdowns. In the Turkish case, a severe economic crisis in 2018/19 preceded the Covid-19 pandemic. Housing output, housing prices, and the unemployment rate were much more affected by the economic crisis than by the pandemic. Spatial variation in the changes in the supply level was not homogeneous throughout the country. Lower supply levels were observed in the southern and south-eastern parts of the country and the major employment centres. However, compared to the international tendencies, total demand for housing increased, raising the housing transaction volume to record-high levels. In addition, housing prices during the pandemic skyrocketed, accompanied by increasing inflation rates. Furthermore, a demand shift towards single-family houses was observed, and the price gap between single-family houses and flats has widened since the pandemic began. The investment function of housing became prominent once again for wealthier households during the high inflation periods observed during the pandemic. The major conclusion drawn from this study is that the housing market deepened the existing inequalities in society during the current pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The first two decades of the twenty-first century have witnessed pivotal events such as economic crises, disasters, international migration, war, and the pandemic, the effects of which have been global. Not all countries have experienced these extreme events equally. However, the devastating effects display similarities, such as the decline in economic activity, increased unemployment rates, worsening housing and living conditions, and increased risk of eviction and homelessness. When the Covid-19 pandemic began in 2020, the world had only just recovered from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Turkey had not been affected much by the GFC. Rather, countries with more liberalised housing finance and real estate markets had been hit by the crisis (Hegedüs and Horvath 2015). The limited negative impacts of the GFC on the Turkish economy and housing sector were due to the lately developed mortgage finance system, less reliance on mortgage finance products, and a highly regulated financial sector (Coşkun 2016; Özdemir Sarı 2019). However, just before the pandemic, Turkey experienced an economic crisis in 2018, the effects of which continued in 2019. The political tension between Turkey and the US triggered the 2018/19 exchange rate crisis (Çakmaklı et al. 2020). The depreciation of the Turkish Lira against the US Dollar and increasing inflation rate followed. Hundreds of firms declared bankruptcy and the official unemployment rate reached record-high levels (Akcay and Güngen 2019).

With the outbreak and spread of Covid-19, governments worldwide adopted several extraordinary measures, such as lockdown orders, restricting business activity, and requiring households to 'isolate at home' to limit social interactions and the spread of the virus. Covid-19 and associated measures had significant consequences on the economy and radically transformed people's lives. Even at the very beginning of the pandemic, researchers highlighted its unique, enormous, and multidimensional nature. For instance, Gopinath (2020), in the article she wrote for the IMFBlog, indicated that this is the 'worst economic downturn since the great depression'. She highlighted the existence of overlapping simultaneous crises and wrote: "This is a crisis like no other, and there is substantial uncertainty about its impact on people's lives and livelihoods…many countries now face multiple crises—a health crisis, a financial crisis, and a collapse in commodity prices, which interact in complex ways." This multiple crisis environment and the increased time spent at home emphasised the role and meaning of housing for households and society like no other crises had before. During this process, the functions of housing have expanded beyond its primary functions of being a shelter, a commodity, and an investment good. Housing has attracted attention, providing/limiting access to open and green spaces, ensuring an adequate/inadequate home office or home-schooling/distant education environment, and being a determinant of households' health conditions. As a result, once again, housing proved to be an indispensable pillar for the well-being of society.

The Turkish economy, housing markets, and households also have been hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic. There was no time for a recovery period after the 2018/19 economic crisis. The pandemic and the measures taken to tackle it have deepened the already existing social, economic, and spatial inequalities. The lockdowns and restrictions experienced during the pandemic have resulted in the shutdowns of many small and medium-sized businesses, including construction firms, leading to lower economic output and increased unemployment. On the other hand, the new living conditions brought about by the pandemic caused changes in housing consumption and preferences of households. Some households managed to adapt to new consumption needs, such as increased physical space requirements, whereas others were hardly surviving in overcrowding with already poor housing conditions.

There is a mutual relationship between the housing markets and the overall economy. Housing markets are vulnerable to economic fluctuations, yet they may also cause a deepening of the economic crisis. Failures in the housing markets may cause several problems, some of which are observed as direct housing outcomes, whereas others emerge as problems in the broader fields. Examples include housing quality and affordability problems, homelessness, unemployment, increased inequality in the distribution of wealth, and a decline in the performance of regional and national economies (Bramley et al. 1996). Therefore, it is essential for urban and regional policies to regularly monitor changes in the housing markets. This monitoring process becomes especially vital in countries where the construction sector plays a significant role in the economy. Turkey is one such country. Our study investigates the trends in the Turkish housing markets under the effects of the 2018/19 economic crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. At present, it is not yet possible to monitor all of the effects of these two events based on evidence since some results are likely to become apparent in the coming years. Still, some of the supply- and demand-side trends in the housing markets are currently observable, and they form the focus of the present paper.

2 Housing market reactions under extreme events

Extreme events such as terrorist attacks and violence (Mills 2002; Hazam and Felsenstein 2007), natural disasters (Hallstrom and Smith 2005; Pommeranz and Steininger 2020), economic crises (Whitehead and Williams 2011; Kennett et al. 2013; Dagkouli-Kyriakoglou 2018), and epidemics and pandemics (Wong 2008; Liu and Tang 2021) all have direct and indirect effects on housing markets. During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, the GFC has been a topic of interest among scholars due to its widespread effects on global and national economies. Although the impact of the credit crunch is over, the world is experiencing a new crisis due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Covid-19 has been the last element included in discussions, at least for the moment, with its uncertain and unexpectedly prolonged effects on the housing market. There is a vast amount of literature focusing on the housing markets in relation to the economic crisis. However, the literature on the effects of epidemics and pandemics in the housing markets is relatively scarce and still emerging.

Economists have stated that the Covid-19 crisis has some similarities to the GFC, such as uncertainty, collapse, and reactions in terms of limiting shocks and monetary and fiscal policies (Strauss-Kahn 2020). Although Covid-19 is a health emergency at the first instance that threatens the lives of people, it also has social, economic, and housing-related implications. Since extreme events such as epidemics and pandemics are exogenous, the standard supply–demand framework is not helpful for understanding and explaining housing market reactions. Furthermore, measuring market reactions to extreme events is extremely difficult since these events include high levels of uncertainty and risk beyond the control of individuals. In such cases, markets may display several different reactions. Therefore, it is not unusual or unexpected to encounter contradictory findings in the literature about housing markets’ reactions to epidemics and pandemics.

2.1 House prices, transaction volumes, and housing output

Existing research usually focuses on the changes in house prices and the transaction volume under the effects of extreme events. Wong (2008, p.80), employing an asset-pricing model, notes that, in theory, prices are likely to change if health risks or reduction in agglomeration benefits cause anticipation of a change in the net present value of future housing services. Her study shows a slight decline (1.6%) in house prices and a significant decline (72%) in transaction volume during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Hong Kong. Francke and Korevaar (2021), based on their investigation of historical outbreaks of the plague and cholera, report that outbreaks negatively affect house prices and rents, yet these are short-lived trends, and declines in rental prices are relatively minor. D’Lima et al. (2022) examined shutdown pricing effects and revealed that densely populated areas experienced a 1.4% price decline, while low-density locations faced a 1.5% increase in prices. Furthermore, they observed a significant decrease in transaction volume.

Wang (2021), on the other hand, reports that after the outbreak only one of the five areas she studied showed declines in house prices. She states that the vulnerability of housing markets might be due to the composition of the local economy and whether it requires face-to-face interactions rather than stay-at-home orders or business restrictions. Duca et al. (2021) focused on the housing markets of various countries, particularly touristic cities in those countries. They show that even though many households experienced decreased disposable income, the demand and housing sector activity remained active in areas mainly composed of secondary housing and detached housing units during the pandemic. Cheshire et al. (2021), in their evaluation of the British housing market during the current pandemic, reveal that new housing supply substantially slowed, and demand shift in preferences towards larger detached and semi-detached houses resulted in quick recovery in the prices of these types of properties.

Contrary to the traditional expectation of an adverse effect on housing markets (Francke and Korevaar 2021), house prices in numerous urban areas increased considerably after the Covid-19 outbreak. This occurred despite the decreasing level of GDP and rising unemployment rates, and limited trade activities due to the lockdowns. However, it must be recalled that in some housing markets a slowed-down housing supply may increase housing prices if there is demand for particular areas or properties (see Cheshire et al. 2021). Alternatively, reshuffling of housing demand may work in a way that positive price effects offset negative ones (D'Lima et al. 2022). Since the lockdowns and restrictive measures imposed during the pandemic had combined supply and demand effects (Gopinath 2020; Allen-Coghlan and McQuinn 2021), it is not surprising that the real estate market responses to these measures are uncertain (D'Lima et al. 2022, p.304).

2.2 Total housing demand, demand shifts, and housing affordability

First-order consequences of extreme events such as epidemics and pandemics on demand for housing are usually a decline in total demand due to the high mortality rates. An increased number of deaths and social and economic instability are expected to result in reductions in rental prices and house prices immediately after an outbreak (Francke and Korevaar 2021). During the current pandemic, however, several extraordinary measures were adopted that resulted in a series of subsequent events that further affected the demand and supply for housing: (i) a significant decline in aggregate consumption due to lockdowns and restrictions, (ii) limited economic output due to reduced labour supply and working hours, (iii) loss of income due to job losses during the collapse of economic activity, (iv) further decline in household expenditure in general. In such a downturn in economic circumstances, housing affordability is usually expected to be affected negatively since declining income levels and increasing unemployment are likely to limit households' borrowing capacity (Allen-Coghlan and McQuinn 2021).

However, three issues are worth mentioning here. On the one hand, these negative impacts affect some households disproportionately. For instance, unemployment or wage cuts are more likely to affect low-income households or minorities (Balemi et al. 2021). This reduces the chances of these populations' entering homeownership and increases their existing housing cost burden as well. On the other hand, housing demand is likely to reshuffle under the complex dynamics of epidemics and pandemics. For instance, Liu and Su (2021), in their neighbourhood-level examination of housing demand variation under the effect of the current pandemic, found that housing demand shifted away from central city neighbourhoods and high-density neighbourhoods. Furthermore, authorities attempt to stimulate the housing market through interest rate cuts in many countries. These attempts would have limited effects in countries with historically low-interest rates (Allen-Coghlan and McQuinn 2021). However, in Turkey, for instance, lowering the cost of finance had a visible impact on stimulating the housing markets (Alkan Gökler 2022). That is to say, the current pandemic's demand-side influences vary with respect to different households, locations, and policies of the countries.

The main conclusions from the existing literature on housing market reactions to extreme events, particularly to the current pandemic, indicate that both the supply and demand sides of the housing markets are confronted with unprecedented challenges. Responses are highly varied with respect to households' economic status and capacity, as well as the dwellings' characteristics and location within the housing market.

3 Trends in the Turkish housing markets

3.1 Data and method of the study

Our study employs a descriptive method in general. Several data sources are employed to represent supply- and demand-side trends. Table 1 displays the variables examined together with their data sources. To investigate the effects of the economic crisis and pandemic separately, the data provided cover the pre-crisis period (before 2018), the crisis period (2018–2019), and the pandemic period (2020–2021).

The analysis of the Turkish case starts with an examination of the changes in housing output. The major question here is whether the annual housing output was negatively affected by the economic crisis and the pandemic and whether the impacts of these extreme events are experienced homogeneously throughout the country. Annual housing starts (construction permits) are used to represent housing output, which better reflects the annual production compared to the information on completions (occupancy permits). Annual housing production is examined in terms of (i) the changes in total output, (ii) the level of output compared to household formation, and (iii) the geographical distribution of the annual housing production compared to household growth. This is followed by an examination of the transaction volumes. At this stage, the total transaction volume and the share of mortgaged sales are examined to see the effects of government intervention (i.e. interest rate cuts) in the housing markets. In the third phase, details of house price development are investigated. Changes in the countrywide nominal and real prices and the sales price changes in flats and single-family homes are examined. The final stage of the analysis focuses on the households. It portrays the changes in (i) unemployment rates, (ii) the number of poor and at risk of poverty rate, (iii) the share of housing expenditure in the household budget, and (iv) housing cost overburden. At the risk of poverty, in line with Eurostat’s definition, is accepted here as the share of the population having an equivalised disposable income below 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income. Further, according to Eurostat, the housing cost overburden rate reflects the percentage of the population living in households where the total housing costs are more than 40% of disposable income.

3.2 Analysis and results

Over the last two decades, a significant surplus of housing stock has been created in Turkey due to subsequent governments' deliberate efforts. Housing output reached record-high levels in 2014, 2016 and 2017, exceeding one million dwelling units annually. This oversupply has resulted in high residential vacancy rates, and a significant share of the vacant stock remained in the hands of construction companies as of 2018 (Kıvrak and Özdemir Sarı 2022). The government implemented several measures during the 2018/19 economic crisis to stimulate housing sales and, by this means, the economy. However, the crisis was severe and more than half of the medium-sized and large enterprises engaged in construction activity closed (Özdemir Sarı 2022). In other words, prior to the pandemic, the Turkish housing market was under the pressure of the 2018/19 economic crisis.

This negative economic climate and the construction sector's shutdowns were reflected in annual housing production levels (Fig. 1). Annual housing production levels started to fall in 2018, and this trend continued in 2019. In 2019 and 2020, annual housing production left behind the average housing supply levels of the last 20 years. However, it must be noted that the effects of the crisis on housing output were far more visible than those of the pandemic. The housing output during and after the 2008 GFC is also observable in Fig. 1, and it appears production levels were less affected by this global event.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on TURKSTAT (2022a)

Annual Housing Starts in Turkey (2005–2021).

One can assume that housing supply levels in the Turkish markets in the 2000s were a response to the new housing need emerging due to the household formation rate. However, in the last 20 years, annual housing production levels exceeded the yearly increases in household numbers most of the time (Türel and Koç 2015). In contrast, under the influence of the economic crisis of 2018/19, in 2019, increases in the number of households dramatically exceeded the annual housing starts (Fig. 2). Although recovering in 2020 and 2021, the number of newly formed households is slightly higher than the newly added dwelling units. This overall view of the country indicates that housing output has been negatively affected during the economic crisis and pandemic. However, observing the changes in housing output and new household formation spatially may contribute to a better understanding of housing markets in terms of the economic crisis and the pandemic (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 compares housing output and additions to households in Turkish provinces for 2018–2021. In Fig. 3, light grey areas represent severe housing shortages, where housing production per added household is below 1. Accordingly, in 19 of the 81 provinces, housing production fell behind the number of newly formed households. In only 3 of the 81 provinces (1.00–1.04 range in the figure) is housing production equal to household growth or allows for a 4% vacancy rate, which is usually regarded as necessary for the smooth operation of the market. The rest of the provinces (60 provinces) display different levels of oversupply, 14 of which have extremely excess production. Reduced supply during 2018–2021 is observed particularly in the southern and south-eastern parts of the country and the major cities and employment centres such as Ankara, İstanbul, and Bursa. The location of the oversupply is far more interesting; it originates from central Anatolia and goes in two directions: to the north and the east. Some provinces lie at extremes when these production trends are compared to the housing shortage and excess production trends in previous periods. A comparison with the findings reported by Özdemir Sarı (2019) reveals that excess production is a chronic issue in 8 of the provinces: Kastamonu, Çorum, Kırşehir, Yozgat, Kayseri, Nevşehir, Niğde, and Elazığ, whereas chronic housing shortage is a problem in 15 provinces: Mersin, Adana, Hatay, Şanlıurfa, Mardin, Diyarbakır, Batman, Şırnak, Hakkari, Van, Muş, Bursa, İstanbul, Bartın, and Karabük. Of these, İstanbul, Bursa, Adana and Mersin are major employment centres.

Turkish housing markets display an opposite trend to the international tendencies in terms of transaction volumes. The effects of the economic crisis on overall housing sales were slight in 2018 and 2019 (Fig. 4). Rather, the share of mortgaged sales declined to 20–25% levels from their usual 33–34% range. Due to the mortgage interest rate cuts in 2020, transaction volumes increased during the first year of the pandemic. With the termination of favourable conditions in mortgage interest rates, in 2021, the share of mortgaged sales declined to 20% from 38% in 2020. However, this has not been reflected greatly in the total sales since house sales to foreigners increased, reaching 3.9% of the total sales in 2021, the highest rate ever observed.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on TURKSTAT (2022e)

House Sales in Turkey (2015–2021).

There are no reliable and complete data for an examination of house price development in Turkey. The house price index, prepared by the CBRT, underrepresents the Turkish housing market since it is based on expert valuation reports of mortgage applications (Özdemir Sarı 2019). Since this index is the only major data source about house prices, the annual changes in nominal and real house prices are presented in Fig. 5 based on these data. It is seen from the figure that real prices started to decline in early 2017, and even negative price development was observed in the third quarter of the same year (Özdemir Sarı 2022). This negative trend resulted from housing bubble discussions prevailing in the country due to the housing production boom of 2014–2017 and an IMF report implying the existence of a housing bubble. In addition, inflation rates were on the rise. The economic crisis in 2018/19 deepened the negative trend in prices.

When the pandemic occurred, prices were recovering slightly. Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020 triggered mobility trends favouring less dense urban areas such as fringe and coastal settlements where most of the summer homes are single-family houses. However, it is difficult to examine these tendencies due to the lack of data. Increased residential mobility combined with mortgage interest rate cuts and low levels of housing output resulted in positive growth in real house prices in 2020. Since the end of 2020, inflation rates have been rising. Officially declared rates reached 36% in December 2021 and 49% in January 2022. This dramatic rise in inflation has recently been reflected in a sharp increase in house prices.

When price trends are further examined separately for new and existing housing through CBRT data (2022a), it is seen that they display exactly the same cycle as the overall house price index. The annual change in house price index remained almost the same for new and existing housing until the fourth quarter of 2019. During 2020 and 2021, the gap between the two indices widened slightly due to the decline in new housing starts during the crisis, rising inflation, and favourable mortgage interest rates for new housing compared to the existing ones. The highest difference is observed in January 2022, with the annual change in the new house price index 10% higher than the existing house price index.

Although the data are limited, it is still possible to observe the demand shift in housing markets favouring single-family houses (Fig. 6). As the figure displays, the sales price gap between flats and single-family houses started to increase in the first half of 2020 with the lockdown measures during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, unit prices of single-family houses were nearly 1.3–1.4 times that of flats. Since the beginning of the pandemic, this ratio has increased to 1.9. Currently, due to the high inflation levels in the country, housing once again serves as a better investment than the alternatives for the wealthier sections of society.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on Endeksa (2022)

Unit Prices for Flats and Single-family Houses: January 2018–January 2022.

On the household side, the data displaying the effects of the pandemic are limited. Table 2 displays the available data on unemployment, number of poor people, at risk of poverty rate, the share of housing expenditure in the household budget, and housing cost overburden for people at risk of poverty.

Accordingly, the economic crisis affected unemployment more than the Covid-19 pandemic did. However, the total number of poor has been continuously increasing since 2017. This is slightly reflected in at risk of poverty rates. As of 2020, 23% of the total population in Turkey is at risk of poverty, earning below 60% of the median equivalised income of the country. The share of housing and rent expenditure in the household budget cannot be examined thoroughly; however, it is expected that household expenditure for housing and rent increased under the lockdown conditions and high inflation. Furthermore, the housing cost overburden rate indicates that the poor segments of the society were affected more than the rest of the society.

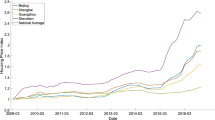

As noted above, according to Eurostat, the housing cost overburden rate reveals the percentage of the population living in households where the total housing costs are more than 40% of disposable income. Figure 7 clearly displays that the increased housing cost burden was borne disproportionately by the lowest end of the income scale during the economic crisis and pandemic. Since 2017 the housing cost overburden rate has been increasing among the lowest income quintile, whereas more stable rates are observed for the rest of the population. Even a reduced housing cost overburden rate was observed for the 4th and 5th quintiles in 2020. In other words, it is the low-income households, as usual, who bear the cost of the economic crisis and the pandemic.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on Eurostat (2022)

Housing Cost Overburden Rate in Turkey for Income Quintiles (2013–2021).

4 Conclusions

When the Covid-19 pandemic occurred, there were already some social, economic, and spatial inequalities all over the world. The pandemic has worsened economic conditions and created a new set of spatial needs. This has had a number of effects on both the supply and demand sides of the housing market. It is not easy to show/monitor all of these effects based on evidence in the current period. A survey of the relevant literature reveals that lockdowns and restrictions applied during the Covid-19 pandemic have negatively affected the supply of housing and transaction volumes; however, the effects on housing prices are not clear. Due to the demand shifts from high-dense areas to low-dense ones, and from flats to detached single-family houses, in some sub-markets prices go up and in others display a decline. The Turkish case shares similarities with other countries' experiences in terms of housing production and demand shifts. However, housing transaction volumes and house price development display different trends.

In the Turkish case, the Covid-19 pandemic was preceded by a severe economic crisis in 2018/19 whose adverse effects on housing markets surpassed those of the pandemic. Housing output, housing prices, and the unemployment rate were much more affected by the economic crisis than by the pandemic. Furthermore, spatial variation in the changes in the supply level was not homogeneous throughout the country. Compared to the international tendencies, total demand for housing increased during the pandemic, elevating housing transaction volume to record-high levels. In addition, housing prices and inflation rates soared during the pandemic. Furthermore, a demand shift in favour of single-family houses is clearly observed. The price gap between single-family homes and flats has been widening since the beginning of the pandemic. However, the contribution of the economic crisis of 2018/19 and the pandemic to the inequality in society's wealth distribution is not clear at the moment. It is concluded that the trends observed in the housing markets during the economic crisis and the pandemic disproportionately affected the poor and low-income households, and the wealth gap in society has widened. Housing is a major factor in this increased inequality since its investment function becomes more prominent during high inflation periods.

Developing policy options for these challenging outcomes of the economic crisis and pandemic is beyond the scope of our study since the aim was to investigate the trends in the housing markets under extreme circumstances. However, it is still possible to mention a few points about coping with the housing markets' adverse outcomes during challenging times. Considering that housing market outcomes during extreme events differ for different income segments, it is clear that at challenging times, such as economic crises or pandemics, special policies are needed to support those population groups that are in need. These groups may be the ones that experience loss of livelihood due to the economic crisis or the lockdowns during the pandemic or those that are already living under substandard housing conditions or that are housing cost-burdened. There was no policy or support for the vulnerable segments in the housing markets in Turkey during the economic crisis and the pandemic. However, considering that adequate housing is a human right, housing policies and interventions should be implemented to protect tenants from forced evictions, provide direct financial support for rent and mortgage arrears, and develop housing assistance programmes for the cost-burdened segments of society. The measures that can be taken are not limited to those listed here. To reduce the vulnerabilities of the housing market during and after extreme events, these vulnerabilities should be understood clearly; thereby, measures specific to the local context and needs could be developed.

References

Akcay Ü, Güngen AR (2019) The making of Turkey’s 2018–2019 economic crisis, Working Paper, No. 120/2019, Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin

Alkan Gökler L (2022) Housing market dynamics: Economic climate and its effect on Turkish housing, In: Özdemir Sarı ÖB, Aksoy Khurami E, Uzun N (Eds) Housing in Turkey: Policy, Planning, Practice. Routledge, London, pp 83–100

Allen-Coghlan M, McQuinn KM (2021) The potential impact of Covid-19 on the Irish housing sector. Int J Hous Markets Analysis 14(4):636–651. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-05-2020-0065

Balemi N, Füss R, Welgand A (2021) COVID-19’s impact on real estate markets: review and outlook. Fin Markets Portfolio Mgmt 35:495–513

Bramley G, Bartlett W, Lambert C (1996) Planning, the market and private house-building: The local supply response. Routledge, London

CBRT (2022a) House Price Index. https://evds2.tcmb.gov.tr/index.php?/evds/serieMarket/collapse_26/5949/DataGroup/turkish/bie_hkfe/ Accessed 30 March 2022a

CBRT (2022b) Consumer Price Index. https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/TR/TCMB+TR/Main+Menu/Istatistikler/Enflasyon+Verileri/Tuketici+Fiyatlari Accessed 30 March 2022b

Cheshire P, Hilber C, Schöni O (2021) The pandemic and the housing market: a British story. Centre for Economic Performance – CEP COVID-19 Analysis. No: 020

Coşkun Y (2016) Housing finance in Turkey over the last 25 years: Good, bad or ugly? In: Lunde J, Whitehead C (eds) Milestones in European housing finance. Wiley, United Kingdom, pp 393–411

Çakmaklı C, Dermiralp S, Kalemli Özcan Ş, Yeşiltaş S, Yıldırım MA (2020) Covid-19 and emerging markets: The case of Turkey, Koç University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum Working Papers No: 2011, Koc University – TUSIAD Economic Research Forum.

Dagkouli-Kyriakoglou M (2018) The ongoing role of family in the provision of housing in Greece during the Greek Crisis. Crit Hous Analysis 5(2):35–45. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2018.5.2.441

D’Lima W, Lopez LA, Pradhan A (2022) COVID-19 and housing market effects: Evidence from U.S. shutdown orders. Real Estate Econom 50:303–339

Duca JV, Hoesli M, Montezuma J (2021) The resilience and realignment of house prices in the era of Covid-19. J Eur Real Estate Res 14(3):421–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/JERER-11-2020-0055

Endeksa (2022) https://www.endeksa.com/tr/ Accessed 15 April 2022

Eurostat (2022) European Union Survey of Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/income-and-living-conditions/data/database Accessed 20 June 2022

Francke M, Korevaar M (2021) Housing markets in a pandemic: Evidence from historical outbreaks. J Urban Econ 123:103333

Gopinath G (2020) The great lockdown: Worst economic downturn since the great depression, IMFBlog: Insights and analysis on economics and finance, https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/ Accessed 10 April 2022

Hallstrom DG, Smith KV (2005) Market responses to hurricanes. J Environ Econ Manag 50:541–561

Hazam S, Felsenstein D (2007) Terror, fear and behavior in the Jerusalem housing market. Urban Stud 44:2529–2546

Hegedüs J, Horvath V (2015) Housing in Europe. In: Housing review 2015: Affordability, livability, sustainability. Habitat for Humanity. https://www.habitat.org/sites/default/files/housing_review_2015_full_report_final_small_reduced.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2022

Housing Research Collaborative (2020) COVID housing policy roundtable report. https://housingresearchcollaborative.scarp.ubc.ca/files/2020/11/FinalReport_COVID-19-Global-Housing-Policies.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2021

Kennett P, Forrest R, Marsh A (2013) The global economic crisis and the reshaping of housing opportunities. Hous Theory Soc 30(1):10–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2012.683292

Kıvrak HK, Özdemir Sarı ÖB (2022) Understanding residential vacancy and its dynamics in Turkish cities. In: Özdemir Sarı ÖB, Aksoy Khurami E, Uzun N (eds) Housing in Turkey: Policy, Planning, Practice. Routledge, London, pp 145–162

Liu S, Su Y (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the demand for density: Evidence from the U. S. housing market. Econ Lett. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2021.110010

Liu Y, Tang Y (2021) Epidemic shocks and housing price responses: Evidence from China’s urban residential communities. Reg Sci Urban Econ 89:103695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2021.103695

Mills ES (2002) Terrorism and U.S. real estate. J Urban Econ 51:198–204

Özdemir Sarı ÖB (2019) Redefining the housing challenges in Turkey: An urban planning perspective. In: Özdemir Sarı ÖB, Özdemir SS, Uzun N (eds) Urban and Regional Planning in Turkey. Springer, Switzerland, pp 167–184

Özdemir Sarı ÖB (2022) The Turkish housing system: An overview. In: Özdemir Sarı ÖB, Aksoy Khurami E, Uzun N (eds) Housing in Turkey: Policy, Planning, Practice. Routledge, London, pp 11–29

Pommeranz C, Steininger BI (2020) Spatial spillovers in the pricing of flood risk: Insights from the housing market. J Hous Res 29(1):54–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10527001.2020.1839336

Strauss-Kahn M (2020) Can we compare the COVID-19 and 2008 crises? https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/can-we-compare-the-covid-19-and-2008-crises/. Accessed 2 Apr 2022

TURKSTAT (2022a) Building Permits by Type of Investor: 2002–2022a. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/DownloadIstatistikselTablo?p=vY0PlN6oDgLQQT0LshEWCz6Uiq4otTySu7kSGdE4gyv4LaxqbQIVyT3mmdL7wVBr. Accessed 3 Apr 2022

TURKSTAT (2022b) Number of Households by Size and Type: 2013–2022b. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/DownloadIstatistikselTablo?p=Klkp5koohrEUzElvc6fFGT82LSaTveoUAwgQgBWDaSHMBRnros6emJXMH3ZBPvdG. Accessed 4 Apr 2022

TURKSTAT (2022c) Building Permit Statistics. https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/yapiizin/giris.zul. Accessed 1 Apr 2022

TURKSTAT (2022d) Number of Households by Type and Provinces: 2016–2021. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/DownloadIstatistikselTablo?p=W5ZgTkmDx3Oyx/ubmqnPJViZt36NsQCKhmeIXp7mtV35tDAxicVOAB3qGHhip0ju. Accessed 2 Apr 2022

TURKSTAT (2022e) House Sales by Type and State: 2013–2022e. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/DownloadIstatistikselTablo?p=zbkcBOwwd49O9IIeiaWFpDOKzT15pLoTnQmTjQsKGns3dy5kTaTxfWiUDdmZ0SUZ. Accessed 2 Apr 2022

Türel A, Koç H (2015) Housing production under less-regulated market conditions in Turkey. J Hous Built Environ 30(1):53–68

Wang B (2021) How does COVID-19 affect house prices? A cross-city analysis. J Risk Financial Mana https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14020047

Whitehead C, Williams P (2011) Causes and consequences? Exploring the shape and direction of the housing system in the UK post the financial crisis. Hous Stud 26:1157–1169

Wong G (2008) Has SARS infected the property market? evidence from Hong Kong. J Urban Econ 63(1):74–95

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Aksoy Khurami, E., Özdemir Sarı, Ö.B. Trends in housing markets during the economic crisis and Covid-19 pandemic: Turkish case. Asia-Pac J Reg Sci 6, 1159–1175 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-022-00251-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-022-00251-w