Abstract

In the recovery from the United States’ 2009 recession, unemployment has proven resistant to both aggressive fiscal policy and expansionary monetary policy. A possible explanation is the policy cost uncertainty hypothesis. This holds that managers of private firms have been rationally avoiding hiring workers in the years after 2010 because of the risk of higher future costs imposed by government policies. However, such a hypothesis cannot be directly tested in standard models of firm behavior. Thus, to formally test the policy cost uncertainty hypothesis, we use a novel “value functional” or “recursive” model of firm behavior, in which managers maximize the value of the business rather than its profits. Using this approach, we demonstrate that policy cost uncertainty affects the hiring decisions of firms, that the response to policy uncertainty is higher in some industries than others, and that the scale of the firm also affects its sensitivity to policy risk. This approach has potentially broad application within business economics, particularly in evaluating investment and hiring decisions; real options; and other aspects of uncertainty, fixed costs, and managerial flexibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Change in total nonfarm payrolls between June 2009 (that is, the end of the second quarter), and March 2011, seasonally adjusted data (Bureau of Labour Statistics May 2011).

State and federal unemployment rates obtained from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

This analysis, by Tasci [2011], is notable for recognizing the signs of sluggish recovery in the first year of the 2011–13 period for which we evaluate the effects of policy cost uncertainty. See the discussion of the model in Section 2.

The policy cost uncertainty hypothesis relies on the assumption that, at least in aggregate, other forms of business risk (such as business cycle, interest rate, weather, supply chain, logistics, and technology risks) did not change substantially after 2010. For many individual businesses, this is clearly not the case. However, as noted in the discussion regarding the real business cycle theory, it is hard to identify one of these as causing persistent unemployment across the entire U.S. economy.

Because we capture these probabilities in a transition probability matrix (where each row sums to one) any nonzero, nonunitary entry means there is at least one other probability that is also nonzero and nonunitary. Therefore, ruling out zero probabilities also rules out the “certainty” case where all probabilities are one.

Baker, Bloom, and Davis [2012] construct an index from various indicators of uncertainty about the economy, including news coverage, expiring tax code provisions, and forecaster disagreement. Such an index provides a very useful metric for uncertainty. Recent events offer a distinction between the “likelihood of a policy-caused cost increase” and “uncertainty about policy-caused costs.” In our model, a likelihood of a tax increase, as perceived by business managers, would be modeled by a relatively high probability of transitioning from a “baseline cost 2010” state to a “high cost 2014” state. In the Baker, Bloom, and Davis uncertainty index, the same perceived likelihood could be presaged by an expiring tax code provision or an intense debate about tax policy, both of which could increase the uncertainty index; or by a surprise imposition of a cost that arises from an administrative action, which may or may not increase the uncertainty index.

The uncertainty index had a substantially elevated level in 2011–13, when compared with the pre-2010 era, which is consistent with the assumption underlying the policy cost uncertainty hypothesis. Of course, all indices vary over time, and the variation in the policy uncertainty index during the 2011–13 period does not disprove the existence of significant policy cost uncertainty.

Thorstein Veblein first described it as “neoclassical,” noting that it relied on thinking about marginal costs and marginal utility, rather than on the notions of production costs that had dominated the “classical” economics of Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

David Ricardo [1846] noted the equivalence, at least in present value terms, of the taxpayer burdens imposed by the government borrowing money and repaying it with future taxes, and simply imposing the taxes directly. This concept, known as “Ricardian Equivalence,” was later formalized by the contemporary economist Robert Barro [1974]. It is sometimes asserted as an implication of rational expectations in fiscal policy, at least in analytical models with intergenerational transfers. Robert Lucas [1976] summarized a general critique of policy implications drawn from Keynesian models as follows: “Given that the structure of an econometric model consists of optimal decision rules of economic agents, and that optimal decision rules vary systematically with changes in the structure of series relevant to the decision maker, it follows that any change in policy will systematically alter the structure of econometric models.”

As the co-author of “Pocketbook Predictions and Presidential Elections” Anderson and Geckil [2004], I must acknowledge that economic conditions (and even prevailing economic theories) affect election results. Economic theory and economic variables are also known to help predict many similar events, as explored by, for example, Fair [2002]. However, even in U.S. presidential elections, where economic conditions have a clear, empirical relationship with voter choices, a significant share of the results cannot be explained by economic conditions. Similarly, one cannot explain fiscal policy at both the state and federal levels (including such events as the “fiscal cliff,” the recurring debates over the debt ceiling, and the debate and subsequent adoption of income tax laws) as being primarily determined by “economic theory.”

In addition to the continuing uncertainty about costs and taxes, employers as of the last quarter of 2013 were still uncertain about whether key mandates, adopted as part of the ACA statute, would be imposed as scheduled, postponed, or changed. On top of this, they would have witnessed breakdowns of individuals’ online enrollment in the federal Health Exchange Marketplace and firms’ online enrollment in the Small Business Health Options Program. Even careful reading of government documents outlining the enacted ACA (e.g., CBO [2011]) could not have sufficed for a confident prediction of future costs.

See Anderson [2013, chapter 15] for the value functional model of the firm, whose definition of the firm requires three factors: a separate legal identity; a profit motive for its owners; and replicable business practices. This definition provides the basis for the mathematical formulation of a value functional equation involving management actions designed to maximize value for the owners of the firm. Value maximization as the principle behind practical business management decision making was introduced in Anderson [2004].

For example, the profit, revenue, and costs of firms in the neoclassical model are typically expressed as functions. Using differential calculus, we can find the first derivative (or “marginal”) of these functions; seeking the maximum of the profit function then produces the marginal cost=marginal revenue rule.

The pioneers in the calculus of variations include Leonhard Euler (1707–83), Johann Bernoulli (1667–1748), and Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813). Karl Weierstrass (1815–97) reformulated and extended the theory in the nineteenth century.

The extensions here include: selection of specific industry and size of company data; creation of an expansive income statement model; inclusion of a “sell assets and close” action, extended numerical results, and sensitivity and robustness tests.

This includes matching specific taxes and costs to specific parts of the income statement, and properly levying income taxes on income imputed or distributed to shareholders. Most private firms in the U.S. are organized as pass-through entities for tax purposes, are not publicly traded, and meet the standard definition of “small”. (See Anderson [2009]). Therefore, the primary representative firms in this analysis are small, privately held firms filing taxes as an S corp. See Appendix II for results for representative C corps.

Both the existence of a solution to a functional equation, and the practical ability to find it, present difficult issues. In this case, we can make use of a proposition and an existence theorem that, together, provide confidence that a solution can be found. First, under the proposition stated by Anderson [2013], such a model of a firm fulfills a set of “human transversality conditions,” including a profit function bounded by the use of replicable business practices, a discount rate between 0 and 1, and other business constraints. The proposition further states that models of firms that meet these conditions fulfill the requirements for the existence theorems outlined in Stokey and Lucas [1989, chapter 4]. Therefore, at least theoretically, the model we outline here has a solution. The practical ability to compose and solve such a problem benefits from improvements in the conceptualization of the state, which is described in Ljungqvist and Sargent [2012, Chapter 1] and Anderson [2013, chapters 15, 16].

This form of a model is sometimes called a Markov Decision Problem (“MDP”), the key variables have the Markov property, meaning that all the useful predictive information is summarized in the current-period’s variables.

This is a simplifying assumption, as most companies are not publicly traded, and investors in those companies should be expected to have underlying discount rates that vary significantly. Note that the use of an equity discount rate implies that general economic uncertainty affecting businesses is taken into account in this model.

Descriptions of this solution algorithm are contained in Stokey and Lucas [1989] and Ljungqvist and Sargent [2012].

The IRS Statistics of Income data is the base for the Almanac of American Business & Financial Ratios (Troy [2008]). Private bank loan applications, as well as IRS data, are the base for the Bizstats data. We also reviewed Census Bureau (2010) data.

The statutory income tax rates for U.S. individual income tax rates are available from many sources, including the IRS. See the references below for additional information. Aggregate corporate income tax burdens are often compiled in a manner that makes federal income taxes on these businesses difficult to distinguish from other state, federal, and local taxes. Therefore, the reported income tax burden for companies in specific industries was used as a guide for the current federal and state business income, gross receipts, and value-added taxes.

Here, the state is inherently two-dimensional, in that it allows for both scale of firm and policy cost regime to vary, plus a third dimension for allowing the business to close. However, listing all possible combinations of these three dimensions would run headlong into the curse of dimensionality, which has bedeviled value functional methods since they were first outlined by Bellman [1957]. Careful model design allows us to collapse the relevant combinations into five total states.

If the most likely transition occurred for the first two years, and then the second most likely in the third year, it would correspond to no cost or tax increases in 2012 and 2013, and significant cost and tax increase in 2014. As actually occurred, taxes increased in 2013, and costs increased for some firms before 2014. This analysis was conducted before the October 1, 2013 rollout of the troubled health-care “exchange” website, and therefore the subjective probabilities here do not take into account any changes in views of uncertainty that occurred after that date.

See Table 2, where the profits for “big staff” are higher than for “small staff” in the baseline cost regime. The model includes one-time adjustment costs to either hire, or lay off workers, so the immediate reward in a period of “hiring” or “laying off” would be somewhat lower, and they would begin earning the full profits from the new scale at the beginning of the next period. As we are considering the 2011–13 time period, many employers could have absorbed the (relatively small) adjustment costs and received the higher profits from operating at a larger scale before 2014 arrived.

The “fiscal cliff” tax changes that were adopted at the end of 2012 went into effect in 2013. Thus, at least in 2013, there was a 100 percent “chance” of a tax increase for many employers.

Dixit and Pindyck [1994] is a seminal reference on the failure of standard discounted cash flow analysis in finance (and the related concept in economics of the neoclassical investment rule) to properly analyze investment opportunities when managers have real options. For a compendium of other readings on real options, see Schwartz and Trigeorgis [2001].

Examining the robustness table in Appendix III reveals that a wide variety of likelihood assumptions produce contractionary results for some firms.

References

Anderson, Patrick L. 2004. Business Economics and Finance: Using Matlab, Simulation Models, and GIS. CRC Press.

Anderson, Patrick L. 2009. “The Value of Private Firms in the United States.” Business Economics, 44 (2): 87–108.

Anderson, Patrick L. 2013. Economics of Business Valuation: Towards a Value Functional Approach. Stanford University Press.

Anderson, Patrick L. and Ilhan K. Geckil . 2004. “Pocketbook Predictions and Presidential Elections.” Business Economics, 39 (4): 7–18.

Baker, Scott, Nicholas Bloom and Steven Davis . 2012. “Uncertainty and the Economy,” Policy Review 175 (October). Additional information and data also retrieved from “Economic Policy Uncertainty” website at: http://www.policyuncertainty.com.

Barro, Robert J. 1974. “Are Government Bonds Net Wealth?” Journal of Political Economy, 82 (6): 1095–1117.

Bellman, Richard E. 1957. Dynamic Programming. Princeton University Press; reissued by Dover, 2003, and Princeton University Press, 2010.

BizStats data on income statements for businesses in selected industries; retrieved from the BizStats website at: http://www.bizstats.com.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011. “Current Employment Statistics.” May.

Census Bureau, 2010. Economic Census 2007, Industry Statistics for the Year 2007.

Congressional Budget Office, 2011. “CBO’s Analysis of the Major Health Care Legislation.” Testimony before the House Subcommittee on Health, Committee on Energy and Commerce, March.

Debreu, Gerard . 1959. The Theory of Value: An Axiomatic Analysis of Economic Equilibrium. Cowles Commission Monograph; reissued 1972, Yale University Press.

Dixit, Avanish and Robert Pindyck . 1994. Investment under Uncertainty. Princeton University Press.

Dreyfus, Stuart . 1965. Dynamic Programming and the Calculus of Variations. Academic Press.

Fair, Ray . 2002. Predicting Presidential Elections and Other Things. Stanford University Press.

Federal Reserve Board, 2012, 2013. “Summary of Commentary on Current Economic Conditions by Federal Reserve District” [“Beige Book”], for October 2012 and October 2013, http://www.federalreserveboard.gov.

Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income, various reports on business tax returns. Retrieved from: http://www.irs.gov.

Ljungqvist, Lars and Thomas J. Sargent . 2012. Recursive Macroeconomic Theory, 3rd ed. MIT Press.

Lucas, Robert . 1976. “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique,.” in The Phillips Curve and Labor Markets, edited by Brunner Karl and Allan H. Meltzer. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 1 American Elsevier.

Marshall, Alfred C. 1920. Principles of Economics, 8th ed. Palgrave Macmillan.

Mas-Colell, Andreu, Michael D. Whinston and Jerry R. Green . 1995. Microeconomic Theory. Oxford University Press.

Muth, John F. 1961. “Rational Expectations and the Theory of Price Movements.” Econometrica, 29 (3), reprinted in The New Classical Macroeconomics. Volume 1. 1992 3–23, International Library of Critical Writings in Economics, vol. 19. Elgar.

National Federation of Independent Businesses, 2011 and 2013. Small Business Economic Trends, November in each year. www.nfib.com.

Ricardo, David . 1846. “Essay on the Funding System.” in The Works of David Ricardo. With a Notice of the Life and Writings of the Author, edited by J.R. McCulloch John Murray, An online version is available at the Online Library of Liberty at: http://oll.libertyfund.org.

Sargent, Thomas J. 2008. “Rational Expectations.” The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Library of Economics and Liberty. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/RationalExpectations.html.

Schwartz, E. and L. Trigeorgis eds. 2001. Real Options and Investment Under Uncertainty: Classical Readings and Recent Contributions. MIT Press.

Stokey, Nancy and Robert E. Lucas (with E.C. Prescott). 1989. Recursive Methods in Economic Dynamics. Harvard University Press.

Tasci, Murat . 2011. “High Unemployment after the Recession: Mostly Cyclical, but Adjusting Slowly,” Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, January.

Troy, Leo . 2008. Almanac of American Business Ratios. CCH Press.

Varian, Hal . 1992. Microeconomic Analysis, 3rd ed. W.W. Norton.

Software

The model was composed and solved using the Rapid Recursive Toolbox for Matlab, which is distributed by Supported Intelligence LLC. Their website is: http://www.supportedintelligence.com.

Matlab is mathematical software distributed by The MathWorks, Inc. Their website is: http://www.mathworks.com.

Additional information

This paper won the Edmund A. Mennis Contributed Papers Award for 2013 and was presented at the NABE Annual Meeting on September 10, 2013.

*Patrick L. Anderson founded Anderson Economic Group in 1996, and serves as a Principal and Chief Executive Officer in the company. Anderson Economic Group is a boutique consulting firm that has been a consultant for states and provinces, manufacturers, retailers, telecommunications companies, colleges and universities, and franchisees. Mr. Anderson has written a number of published works, including the recently released Economics of Business Valuation. Anderson is a graduate of the University of Michigan, where he earned a Master of Public Policy degree and a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science.

Appendices

Appendix I

Transition probability matrices

Appendix II

Representative C corp results

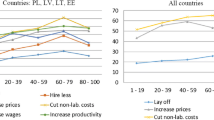

To test our model for robustness, we examined its performance when applied to different industries and firms with different tax structures. We investigated two representative C corporations in the manufacturing industry: one manufacturing transportation equipment and the other industrial machinery.

There are important differences between these C corps and the S corps described in the body of this article:

-

1

Wages and benefits take a much higher share of revenue for service industry employers than for most manufacturers. Manufacturers also typically face more procyclical demand.

-

2

For a firm organized as an S corporation, income is taxed only at the shareholder level. This means that the firm itself does not pay income tax; rather it passes those responsibilities on to its shareholders. In a C corporation, however, the income is essentially taxed twice: once when earned by the firm, and then again when distributed to shareholders. However, many such shareholders are participants in tax-exempt or tax-deferred pension and retirement plans, so their income tax burden on company earnings is diffused.

-

3

Large, publicly traded corporations generally have centrally managed employee benefit plans and workforces that are much larger than the thresholds for “small” business in the ACA. Thus, the incremental benefit administration cost for such firms in the “high cost” regimes are likely to be a smaller fraction of wages than for small, privately held companies.

We present results for one representative manufacturer below. It has revenues of approximately $150 million; has much higher material costs relative to revenue than typical employers in service industries; pays relatively high average wages and benefits; pays a relatively low total corporate income tax as a share of revenues; has dividends that are subject to income taxes paid by those investors that are fully taxable persons; and operates in an industry where a large-scale supplier, even if it currently unprofitable, has a substantial value to potential acquirers.

The results indicate that this manufacturer rationally hires workers, even if it expects that, at some time in the future, costs and taxes will go up. The immediate gain in profits from achieving a higher scale more than outweigh, for this firm, the potential future risks. The decision rule for a value-maximizing firm is different than for a profit-maximizing firm. However, as is illustrated in Table A5, for this firm under these assumptions, the results are the same. In contrast, the decision rules produced different results for the representative restaurant in Table 5 of the body of this article.

Appendix III

Robustness test results

This appendix demonstrates the robustness of the results of the model to changes in various model parameters. In the table below, shaded cells indicate parameterizations of the model that result in contractionary behavior by the subject employer, either through the maintenance of small staff levels when the profit-maximizing action would be to hire workers, laying off of workers, or selling assets and closing when costs go up.

The baseline assumptions are detailed in the body of this paper. To test the robustness of the results, we varied the following parameters: cost increases from 2010 to 2014, possible selling price of the subject company, the probability of costs staying at the baseline level, and the probability of costs remaining high after a change. Not shown in the table, but also included in a suite of robustness tests, were variations on the adjustment costs, which had the expected results of dampening or increasing, but not eliminating, the contractionary hiring behavior.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, P. Persistent Unemployment and Policy Uncertainty: Numerical Evidence from a New Approach. Bus Econ 49, 2–20 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/be.2013.32

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/be.2013.32