Abstract

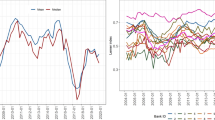

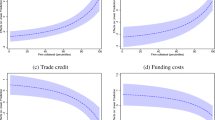

In the context of rapid credit growth, the present paper investigates the supply side of the Serbian credit market. We use an on-site survey of banks aiming to describe financial intermediation by scanning the interest rates and other lending terms in Serbia. Findings from the survey suggest that the credit market is largely non-homogeneous and segmented, but with an increasing presence of competition. Motivated by these findings, we further use an original data set from the financial statements of Serbian banks for a time span of 2001–2005. Using both qualitative and quantitative approaches, we observe the existence of segments in the banking sector. One segment is characterised by a stronger presence of foreign banks, higher transparency of clients and stronger effects of competition on lending interest rates (lower spreads). Another segment is one with more domestic banks, less transparent borrowers, and relatively higher banks’ market power (higher intermediation spreads). The sources of segmentation are in our case represented by funding costs and ultimately by bank ownership. Using the GLS estimator on our panel data set, we estimate the main determinants of bank interest margins as indicators of market power on the individual bank level. Then we test the effect of foreign bank presence on overall asset quality. We use the model developed by Dell'Ariccia and Marquez (2004) in order to explain the results of our regressions and to describe the segmentation. Their model stresses the role of information in shaping bank competition, where a lender with an information advantage (in the case of Serbia, local banks) competes with an outside lender (foreign-owned banks) with less information, but potentially having a cost advantage in extending a loan. We believe that the proposed pattern of segmentation is in place in the Serbian lending market. The findings from the qualitative survey support this argument as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See the conference on ‘Finance and consumption workshop’ held at Florence in June 2006.

In all transition economies except Slovenia, after 10 years of transition foreign ownership became the dominant type of bank ownership.

The banking survey was arranged in the period August–October 2005 with FREN (Foundation for the Advancement of Economics, founded by the Faculty of Economics of the University of Belgrade and the Center for Advanced Economic Studies – CEVES). The survey covered 19 out of 41 currently operating banks, representing 66% of total banking assets as of 30 September 2005.

See Vives (2001), ‘Competition in the Changing World of Banking’, for an overview of the literature.

As suggested in Vives (2001): ‘Different countries may have different optimal levels of competition intensity. Countries with a strong regulatory structure where risk based insurance and informational disclosure can be implemented to a high degree and with relatively low social costs of failure will benefit from vigorous rivalry. To the contrary, emergent and developing countries’ economies with a weak institutional structure and high social costs of failure should moderate the intensity of competition’.

The Serbian banking system reposed on the Yugoslav banking system, which differed from the other centrally planed financial systems of the region. However, after a decade of social and economic decay, Serbia entered 2000 with a banking system that was not only unreformed, but burdened by bad and shameful memories of frozen citizens’ foreign currency savings in 1992, historic record hyperinflation (1992–1993), and pyramid schemes. These phenomena all manifested the abuse of the banking system for political purposes and reflected in the banks’ balance sheets in roughly the following way. On the liabilities side, as EUR 4.2 billion of old ‘frozen’ foreign currency citizens’ savings and respective interests due, about EUR 6.5 billion of liabilities for loans from the Paris and London club of creditors that banks channeled to the economy acting as a primary debtor toward foreign creditors. On the assets side – the bad loans in the same amount were placed mainly in several large state controlled companies, which were able to benefit from such loans for social and political purposes. But besides these, the private sector hardly survived during the 1990s; it relied mainly on self-financing from own accumulation, while citizens relied largely on foreign currency remittances. Although accounting for 200% of GDP (EUR 12.4 billion) in 2000, the banking system was almost non-existent, its ‘dead’ part representing about 70% of total banking assets at the end of the 1990s. At the same time, the banking system was highly controlled and artificially concentrated (five large state-controlled banks represented 63% of banking assets on 31 December 2000) and contained too many banks (87 at the end of the year 2000) compared to other economies of similar size. Many of the small banks that emerged during the 1990s served to satisfy their owners’ financing needs and those of their closely related parties. Prudential supervision of banks was very lax throughout the pre-reform period, resulting in a highly under-capitalized, inefficient, and unprofitable banking system at the eve of the reforms (see Table 2 for the year 2000). The new government (established in October 2000) committed itself to reforming the economy and radical reforms aiming to promote a sound and efficient financial system were undertaken in the banking sector.

In almost all transition economies, except Slovenia, after 10 years of transition it became a dominant type of bank ownership.

See for example Duenwald et al. (2005) for an analysis of credit booms in Bulgaria, Romania, and Ukraine.

As stated in Duenwald et al.( 2005, p. 13) for the cases of Bulgaria, Romania, and Ukraine: ‘Many of the banks’ foreign owners are domiciled in less profitable mature markets, so parents have encouraged their subsidiaries and branches to pursue aggressive loan portfolio expansion to gain market share and improve consolidation results, thereby contributing to the acceleration of credit’.

The banks operate on the securities market as well, but these activities are of limited scope since the equity market remains underdeveloped during the whole period.

Since the central bank statistics did not consistently follow the interest rates, the aim of the survey was initially to document the interest rates in Serbian banks – both lending rates and deposit rates – and to describe their main determinants. For a detailed report on the survey, see Quarterly Monitor issue no. 2 by FREN, www.fren.org.yu.

Monetary policy was very restrictive in order to slow down inflationary pressures. Aiming to make the banks’ sources of funds more expensive, the central bank was increasing the statutory reserve requirements on deposits and received short-term loans, and it sterilized liquidity through repo contracts with attractive interest rates.

The questions asked in the survey were whether and how often the interest rates changed, and what the nature of revised decisions on lending rates was in the first half of 2005. With retail lending, in 15 out of 19 banks that answered these questions, the revised decision on interest rates related to the decline of their general level. Only in one case, the retail lending rates increased. With lending to enterprises, eight out of 17 banks made decisions to reduce interest rates, while one-third of the changes related to the altered elements included in the final interest rate.

Ehrmann et al. (2003) estimate the effects of monetary policy across banks on both BankScope (commercial database with a partial coverage of national banking systems) and Eurosystem data (covering the full population of banks in a country, collected by national central banks) in four large countries of euro area. They find significantly different results on BankScope data with incomplete coverage.

National Bank of Serbia, Rules on the chart of accounts and content of accounts within the chart for banks and other financial organisations.

National Bank of Serbia, Rules on forms and content of individual items in financial statement forms to be completed by banks and other financial organisations.

This kind of distortion is common for all transition economies, representing a serious obstacle for quantitative analyses of these economies. However, we have not found a discussion dedicated to this methodological issue in any studies analysing banking systems based on banks’ accounting data.

The dealership approach for analysis of banks is developed by Ho and Saunders (1981), extended by Allen (1988). The dealership approach is particularly convenient for analysing bank spreads in the Serbian case, since most bank activities consist of credit granting and deposit taking (the securities business is very poorly developed, as well as services), just as the model assumes.

The firm-theoretical framework uses a micro-model of banking firm, based on the approach of Klein (1971) and Monti (1972) and extended by Zarruck (1989) and Wong (1997).

Decision on Criteria for the classification of balance sheet and off-balance sheet items according to the level of collectability and special provisions of banks and other financial organisations (RS Official Gazzette, No. 37/2004, 86/2004, and 51/2005).

For use and misuse of the aggregate measure of non-performing loans for the whole country by classification of assets in risk categories according to the prescribed criteria, and its comparison to aggregate measure of overdue loans for 90 days and more, see Dimitrijevic (2006).

In Appendix C, we present all variables as they are calculated and descriptive statistics for all banks, as well as by different ownership categories.

See, for example Vittas (1991) ‘Measuring commercial bank efficiency, use and misuse of bank operating ratios’, IMF WPS; and also Financial Sector Assessment: A Handbook, IMF/the World Bank, September 2005; and Compilation Guide on Financial Soundness Indicators, IMF (2003) for detailed issues to be considered in the use of different measures of bank performance.

A simple t-test on funding cost differences over ownership categories shows a statistical significance at 1% – with higher funding costs for domestic banks.

This means that there is probably no need for concern about the endogeneity problem here.

References

Allen, L . 1988: The determinants of bank interest margins: A note. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 23: 231–235.

Berger, AN and DeYoung, R . 1997: Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. Journal of Banking and Finance 21: 849–870.

Bonin, J, Hasan, I. and Wachtel, P . 2004: Privatization matters: Bank efficiency in transition countries. BOFIT Discussion paper no.8, Bank of Finland.

Claessens, S, Demirguc-Kunt, A and Huizinga, H . 2001: How does foreign entry affect domestic banking markets? Journal of Banking and Finance 25 (5): 891–911.

Claessens, S and Laeven, L . 2003: What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. World Bank Policy Research paper no. 3113.

Clarke, RGG, Cull, R, Peria Soledad Martinez, M and Sanchez, S . 2001: Foreign bank entry: Experience, implications for developing countries, and agenda for further research. Policy Research Working paper series, no. 2698, The World bank.

Coricelli, F, Mucci, F and Revoltella, D . 2006: Household credit in the New Europe: Lending boom or sustainable growth? CEPR Discussion paper no. 5520.

Dell'Ariccia, G and Marquez, R . 2004: Information and bank credit allocation. Journal of Financial Economics 72 (1): 185–214.

Detragiache, E and Tressel, T . 2006: Foreign banks in poor countries: Theory and evidence. IMF Working paper, WP/06/18.

Dimitrijevic, J . 2005: Interest rates in Serbia. Quarterly monitor of economic trends and policies in Serbia, no. 2, CEVES.

Dimitrijevic, J . 2006: Non performing loans in Serbia – What is the right measure? Quarterly monitor of economic trends and policies in Serbia, no. 7, CEVES.

Duenwald, C, Gueorguiev, N and Schaechter, A . 2005: Too much of a good thing? Credit booms in transition economies: The cases of Bulgaria, Romania, and Ukraine. IMF Working paper no. WP/05/128.

EBRD. 2006: Transition report 2006, Finance in transition. November, London.

Ehrmann, M, Gambacorta, L, Martinez-Pages, J, Sevestre, P and Worms, A . 2003: The effects of monetary policy in the euro area. Oxford Review of Economic Policy (19): 58–72.

Ho, T and Saunders, A . 1981: The determinants of bank interest margins: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 4: 581–600.

IMF. 2003: Compilation Guide on Financial Soundness Indicators. IMF, Washington, DC.

Kim, M, Kristiansen, E and Vale, B . 2005: What determines banks’ market power? Akerlof versus Herfindahl. Working paper 2005/8, Norges Bank.

Klein M . 1986: A theori of the bankingfirm. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 3: 205–218.

Kraft, E and Jankov, LJ . 2005: Does speed kill? Lending booms and their consequences in croatia. Journal of Banking and Finance (29): 105–121.

Levine, R . 2003: Denying foreign bank entry: Implications for bank interest margins. Working paper, no. 222, Central bank of Chile.

Mamatzakis, E, Staikouras, C and Koutsomanoli-Fillipaki, N . 2005: Competition and concentration in the banking sector of the South Eastern European region. Emerging Market Review 6 (2): 192–209.

Monti, M . 1972. Deposit, credit and intrest rate determination under alternative bank objectives. In: Szego GP and Shell K (eds). Mathematical Methods in Investment and Finance. North-Holland: Amsterdam.

National bank of Serbia. 2004, 2005 and 2006: Banking system report. various issues.

National bank of Serbia. 2006: Statistical bulletin. various issues.

National bank of Serbia##Decision on criteria for the classification of balance sheet and off-balance sheet items according to the level of collectability and special provisions of banks and other financial organisations. Official Gazzette of the Republic of Serbia, no. 37/2004, 86/2004 and 51/2005.

National Bank of Serbia##Rules on forms and content of individual items in financial statement forms to be completed by banks and other financial organizations.

National Bank of Serbia##Rules on the chart of accounts and content of accounts within the chart for banks and other financial organisations. Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 133/2003 and 4/2004.

Rossi, S, Schwaiger, M and Winkler, G . 2005: Managerial behavior and cost/profit efficiency in the banking sectors of Central and Eastern European Countries. Working paper no.96, Osterreichische Nationalbank.

Soledad Martinez Peria, M and Mody, A . 2004: How foreign participation and market concentration impact bank spreads: Evidence from Latin America. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 36 (3): 511–537.

Vittas, D . 1991: Measuring commercial bank efficiency, use and misuse of bank operating ratios. IMF WPS 806.

Vives, X . 2001: Competition in the changing world of banking. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 17 (4): 535–547.

Wong, KP . 1997: On the determinants of bank interest margins under credit and interest rate risk. Journal of Banking and Finance 21: 251–271.

Zarruck, ER . 1989: Bank margin with uncertain deposit level and risk aversion. Journal of Banking and Finance 14: 803–820.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Kori Udovicki for her precious comments and suggestions in performing the banking survey and analysis of collected data. We also thank the organizers of the Conference on Risk, Regulation and Competition: Banking in Transition Economies in Ghent University, 1–2 September 2006. We want especially to thank Vesna Dimitrijevic for her help in database construction. We like to thank Olivier Lamotte, Ramona Jimborean, Milica Uvalic, Richard Pomfret, Jules-Armand Tapsoba, and an anonymous referee for very helpful comments on an earlier draft and Irena Cerovic and Branka Maricic for their assistance in language editing. All remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX C

APPENDIX D

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dimitrijevic, J., Najman, B. Inside the Credit Boom: Competition, Segmentation and Information – Evidence from the Serbian Credit Market. Comp Econ Stud 50, 217–252 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2008.1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2008.1