Abstract

This paper evaluates tax credits for residential energy efficiency enacted by the Energy Policy Act of 2005, using taxpayer microdata and state-level data on electricity costs, climate, and other factors that might affect demand for energy efficiency. Tax credits for residential energy efficiency are found to be vertically inequitable. Taxpayers that live in states with colder winters are more likely to claim tax credits for residential energy efficiency, while taxpayers in states with higher electricity costs claim higher tax credit amounts (in dollar terms).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Sec.25C.

Residential energy efficiency tax incentives were first adopted under the Energy Tax Act of 1978. The energy efficiency tax credits enacted in 2005 were similar to those that were available from 1978 through 1985 [Crandall-Hollick and Sherlock 2012].

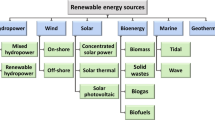

Tax incentives for residential renewable or efficient energy property, including solar panels, solar hot water heaters, and fuel cell power plants, were also introduced in the 2005 Act. Solar property was eligible for a 30 percent tax credit, up to $2,000. The credit for fuel cell property was also 30 percent, limited to $500 per half kilowatt (kW) of capacity. The tax credit for residential renewable energy property has since been extended through 2016. Small wind systems and geothermal heat pumps were added to the list of eligible property in 2008. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act removed credit limits for eligible property other than fuel cells.

It is possible that some of the residential energy credit claims of $500 or less in 2006 and 2007 were for property qualifying for tax credits under IRC Section 25D, such as solar panels. However, this is likely a very small part of the sample. Using data on the number of residential energy credit claims in 2008 relative to 2007, and estimates of the proportion of claims in 2008 that were for less than $500, less than 2 percent of the tax credits claimed in 2006 or 2007 that were less than $500 were for property qualifying for tax credits under Section 25D.

While the parameters for residential energy efficiency credits were the same in 2011 and in 2006 and 2007 (i.e., a 10 percent credit with a lifetime cap of $500), the average value of tax credits claimed in 2011 was substantially higher than the average value of credits claimed in 2006 and 2007 ($459 as opposed to $230 and $233). One possible explanation is that a greater proportion of residential energy credits were being claimed for solar panels in 2011 (which still qualified for a 30 percent unlimited credit) than had been in 2006 and 2007. Another potential explanation for the difference would be the bundling of energy efficiency projects that qualify for the credit.

Individual public use files for tax years beyond 2008 were not available at the time this paper was written.

Since the focus of this paper is on taxpayers claiming credits for residential energy efficiency improvements, the distributional analysis includes only taxpayers claiming $500 or less in residential energy tax credits.

State identifying information is available for 145,872 observations representing 267.2 million individual tax forms. The limitation of state indicators reduces the data set by nearly 48 percent in terms of observations, but only 3.2 percent after accounting for the weights in the data. The additional state-level variables added to the analysis did not include Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, and US citizens abroad. When using the data set expanded with state-level covariates, there are 143,715 observations representing 266.1 million individual tax forms. Further restricting the data set to individuals whose residential energy credits were less than or equal to $500 was 279,258 (275.9 million weighted) observations, which when limited to those with state identification left only 145,820 (267.2 million weighted observations), and when limited to those with state-level data 143,663 (266.1 million weighted) observations remained.

Alternatively, it could mean that property tax payments and mortgage interest expenses were low enough so that the taxpayer elected to claim the standard deduction rather than itemize deductions.

Data on the hybrid car market share ranks individual states in terms of the percentage of registrations that are hybrid automobiles. In 2006, Oregon had the most hybrid automobile registrations per capita, and Oklahoma ranked 51st [Diamond 2008, 2009].

Dastrup et al. [2012] find that solar panels are capitalized into home prices with a larger premium in communities with a higher share of Prius ownership.

This data is available from the Federal Election Commission, http://www.fec.gov/pubrec/fe2004/federalelections2004.shtml.

Marginal effects at the mean are estimated using mean values for each right-hand side variable, which are a quicker and generally cruder way to calculate marginal effects. MEM estimates were not reported here out of concerns for space, and because the magnitudes are very similar to the AME values reported here. These additional estimates are available upon request.

Since values of tax liability and non-REC credits can be 0, a 1 was added to each observation so that logs could be used in the analysis. The natural log for income, tax liability, and non-REC credits, were used since the probability of taking energy credits was non-linear in these variables, and squared income terms resulted in non-convergence in the probit model. In non-reported robustness checks, the effect of log income was similar across specifications when limiting the regression to only those individuals with positive tax liabilities.

Poterba and Sinai [2008] show that most home owners itemize, particularly in higher income groups. Thus, identifying likely home owners as those claiming deductions for mortgage interest or property taxes should identify a large portion of home owners in the sample.

Pseudo R2 values are not interpreted the same way as typical R2 measures, in that they are not a direct measure of the models’ explanatory power.

The excluded state was California. Nearly all states had a higher probability of take-up relative to California. The top three states in terms of take-up were Michigan, New Hampshire, and Iowa with each having more than 5 percent of taxpayers claiming the residential energy credit.

Owing to lack of state-level data for Puerto Rico, an additional 2,157 observations (0.4 percent of weighted observations) were eliminated from the analysis relative to the state-level dummy specification.

Recall that the analysis was limited to claims of residential energy tax credits of $500 or less. Thus, most claims of tax credits for purchases of solar panels or other residential renewable energy property were excluded.

The AME results at specific values are not reported, but can be made available upon request.

It is possible that home owners identified as such through claims of itemized deductions are more likley to pay attention to the availability of other tax incentives, and thus more likely to report energy efficiency expenditures that qualify for tax credits. If this were the case, the indication of home ownership used here would be positively associated with the amount invested in residential energy efficiency. While this is a possibility, it seems unlikely. Linear regressions including the likely home ownership variable confirm that there is no significant relationship with the level of residential energy credit claimed.

Unreported state-dummy variable coefficients for specification 2 indicate that there may be a benefit to being close to Washington DC in terms of the amount of the credit claimed. Compared with residents of California, residents of Washington DC, Maryland, and Delaware each claimed a significantly larger amount for their residential energy credits. Claims were larger on the order of 29 percent in Maryland, 44 percent in Delaware, and 86 percent in Washington DC Only residents of these states — and Puerto Rico or other territories — claimed significantly more than residents of California (the excluded dummy category). States that claimed significantly less than Californians included Wisconsin, Colorado, Massachusetts, Missouri, Indiana, and Rhode Island where claims were between 23 and 41 percent less.

References

Crandall-Hollick, Margot L., and Molly F. Sherlock . 2012. Residential Energy Tax Credits: Overview and Analysis. CRS Report R42089. Washington DC: Congressional Research Service.

Dastrup, Samuel, Joshua S. Graff Zivin, Dora L. Costa, and Matthew E. Kahn . 2012. Understanding the Solar Home Price Premium: Electricity Generation and “Green” Social Status. European Economic Review, 56 (5): 961–973.

Diamond, David . 2008. Public Policies for Hybrid-Electric Vehicles: The Impact of Government Incentives on Consumer Adoption. Ph.D. dissertation. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University.

Diamond, David . 2009. The Impact of Government Incentives for Hybrid-Electric Vehicles: Evidence from U.S. States. Energy Policy, 37 (7): 972–983.

Dubin, Jeffery A., and Steven E. Henson . 1988. The Distributional Effects of the Federal Energy Tax Act. Resources and Energy, 10 (3): 191–212.

Eissa, Nada, and Hilary W. Hoynes . 2004. Taxes and the Labor Market Participation of Married Couples: The Earned Income Tax Credit. Journal of Public Economics, 88 (9–10): 1931–1958.

Eissa, Nada, Henrik J. Kleven, and Claus T. Kreiner . 2008. Evaluation of Four Tax Reforms in the United States: Labor Supply and Welfare Effects for Single Mothers. Journal of Public Economics, 92 (3–4): 795–816.

Hassett, Kevin A., and Gilbert E. Metcalf . 1995. Energy Tax Credits and Residential Conservation Investment. Journal of Public Economics, 57 (2): 201–217.

Heckman, James J. 1979. Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error. Econometrica, 47 (1): 153–161.

Johnson, Rachael A., James Nunns, Jeffery Rohaly, Eric Toder, and Roberton Williams . 2011. Why Some Tax Units Pay No Income Taxes, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/UploadedPDF/1001547-Why-No-Income-Tax.pdf. Washington DC: Tax Policy Center.

Kahn, Matthew E., and Ryan K. Vaughn . 2009. Green Market Geography: The Spatial Clustering of Hybrid Vehicle Registrations and LEED Registered Buildings. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy: Contributions, 9 (2): 1–22.

Newsome, Michael A., Glenn C. Blomquist, and Wendy S. Romain . 2001. Taxes and Voluntary Contributions: Evidence from State Tax Form Check-off Programs. National Tax Journal, 54 (4): 725–740.

Pierce, Kevin . 2010. General Description Booklet for the 2006 Public Use Tax File. Washington DC: Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Division.

Poterba, James, and Todd Sinai . 2008. Tax Expenditures for Owner-Occupied Housing: Deductions for Property Taxes and Mortgage Interest and the Exclusion of Imputed Rental Income. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 98 (2): 84–89.

Puhani, Patrick A. 2000. The Heckman Correction for Sample Selection and Its Critique. Journal of Economic Surveys, 14 (1): 53–68.

Sexton, Steven E., and Alison L. Sexton . 2011. Conspicuous Conservation: The Prius Effect and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Bona Fides. Working Paper WP–029, Berkeley, CA: University of California at Berkeley.

Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA). 2011. Processes were not Established to Verify Eligibility for Residential Energy Credits. Reference Number 2011–41–038. Washington DC: Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Library of Congress or the Congressional Research Service. The authors would like to thank John Anderson and participants at the 2011 National Tax Association annual meeting for comments on an earlier draft. The authors would also like to thank Vipul Bhatt, William Gentry, and anonymous referees for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neveu, A., Sherlock, M. An Evaluation of Tax Credits for Residential Energy Efficiency. Eastern Econ J 42, 63–79 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.35

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.35