Abstract

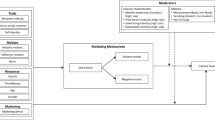

The authors propose a symbolic–instrumental interactive framework of consumer–brand identification (CBI) and explore its predictiveness across 15 countries. Using multinational data, they show that the negative impact of the misalignment between self–brand congruity and perceived quality on CBI is universal. The interaction among CBI, perceived quality, and uncertainty avoidance orientation in motivating consumers’ identity-sustaining behavior is weak. However, the synergy between CBI and perceived quality in motivating consumers’ identity-promoting behavior is stronger among collectivist consumers. The authors derive a typology of symbolic–instrumental misalignments to help international marketing managers motivate consumers to identify with and promote brands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These five categories reflect variation in terms of their symbolic, sensory, and functional meaning (Park, Jaworski, & MacInnis, 1986; Roth, 1995). The ten brands are: Heineken, Budweiser, Nike, Adidas, Nokia, Motorola, McDonald's, Burger King, eBay, and Amazon.

Country-specific correlation matrices are available on request.

Note that we do not propose that the two drivers are equally important across all product categories.

References

Aaker, J. L. 1997. Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34 (3): 347–356.

Agustin, C., & Singh, J. 2005. Curvilinear effects of consumer loyalty determinants in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing Research, 42 (1): 96–108.

Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. 2005. Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (3): 574–585.

Arnett, D. B., German, S. D., & Hunt, S. D. 2003. The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing. Journal of Marketing, 67 (2): 89–105.

Arnold, K. A., & Bianchi, C. 2001. Relationship marketing, gender, and culture: Implications for consumer behavior. In M. C. Gilly & J. Meyers-Levy (Eds), Advances in consumer research, (Vol. 28): 100–105. Valdosta, GA: Association for Consumer Research.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14 (1): 20–39.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. 2008. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34 (3): 325–374.

Ashok, K., Dillon, W. R., & Yuan, S. 2002. Extending discrete choice models to incorporate attitudinal and other latent variables. Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (1): 31–46.

Bagozzi, R. P. 1975. Marketing as exchange. Journal of Marketing, 39 (4): 32–39.

Bagozzi, R. P. 1995. Reflections on relationship marketing in consumer markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (4): 272–277.

Bagozzi, R. P. 2000. On the concept of intentional social action in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (3): 388–396.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Dholakia, U. M. 2006. Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. International Journal of Research Marketing, 23 (1): 45–61.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Lee, K. H. 2002. Multiple routes for social influence: The role of compliance, internalization, and social identity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65 (3): 226–247.

Belk, R. W. 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15 (2): 139–168.

Bergami, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. 2000. Self-categorization, affective commitment, and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identity in the organization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39 (4): 555–577.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. 2003. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67 (2): 76–88.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Rao, H., & Glynn, M. A. 1995. Understanding the bond of identification: An investigation of its correlates among art museum members. Journal of Marketing, 59 (4): 46–57.

Bockman, V. M. 1971. The Herzberg controversy. Personnel Psychology, 24 (2): 155–189.

Bolton, L. E., & Reed II, A. 2004. Sticky priors: The perseverance of identity effects on judgment. Journal of Marketing Research, 41 (4): 397–410.

Brewer, M. B. 1979. Ingroup bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive–motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 86 (2): 307–324.

Broderick, A. J. 2007. A cross-national study of the individual and national-cultural nomological network of consumer involvement. Psychology and Marketing, 24 (4): 343–374.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. 1997. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61 (1): 68–84.

Brown, T. J., Barry, T. E., Dacin, P. A., & Gunst, R. F. 2005. Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33 (2): 123–138.

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65 (2): 81–93.

Chin, W. W. 1998. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed), Modern methods for business research: 295–336. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dawar, N., & Parker, P. 1994. Marketing universals: Consumers’ use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality. Journal of Marketing, 58 (2): 81–95.

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. 1991. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28 (3): 307–319.

Donavan, D. T., Brown, T. J., & Mowen, J. C. 2004. Internal benefits of service-worker customer orientation: Job satisfaction, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 68 (1): 128–146.

Donavan, D. T., Janda, S., & Suh, J. 2006. Environmental influences in corporate brand identification and outcomes. Journal of Brand Management, 14 (1–2): 125–136.

Donthu, N., & Yoo, B. 1998. Cultural influences on service quality expectations. Journal of Service Research, 1 (1): 178–185.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. 1994. Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39 (2): 239–263.

Epstein, S. 1980. The self-concept: A review and the proposal of an integrated theory of personality. In E. Staub (Ed), Personality: Basic aspects and current research: 82–132. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Erdem, T., Swait, J., & Valenzuela, A. 2006. Brands as signals: A cross-country validation study. Journal of Marketing, 70 (1): 34–49.

Escalas, J. E., & Bettman, J. R. 2005. Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 32 (3): 378–389.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (1): 39–50.

Fournier, S. 1998. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24 (4): 43–73.

Gardner, B. B., & Levy, S. J. 1955. The product and the brand. Harvard Business Review, 33 (2): 33–39.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., & Kumar, N. 1999. A meta-analysis of satisfaction in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (2): 223–238.

Guadagni, P. M., & Little, J. D. C. 1983. A logit model of brand choice calibrated on scanner data. Marketing Science, 2 (3): 203–238.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19 (2): 139–151.

Herzberg, F. 1966. Work and the nature of man. Cleveland, OH: World Publishing Company.

Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., & Hoyer, W. D. 2009. Social identity and the service-profit chain. Journal of Marketing, 73 (2): 38–54.

Jarvis, C., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. 2003. A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30 (2): 199–218.

Katz, D. 1960. The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24 (2): 163–204.

Keller, K. L. 1993. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57 (1): 1–22.

Keller, K. L. 2008. Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity, 3rd edn., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Kirkman, B. L., & Shapiro, D. L. 2001. The impact of cultural values on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in self-managing work teams: The mediating role of employee resistance. Academy of Management Journal, 44 (3): 557–569.

Kleine, S. S., Kleine III, R. E., & Allen, C. T. 1995. How is a possession “me” or “not me”? Characterizing types and an antecedent of material possession attachment. Journal of Consumer Research, 22 (3): 327–343.

Kramer, R. M., Brewer, M. B., & Hanna, B. A. 1996. Collective trust and collective action: The decision to trust as a social decision. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research: 357–389. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kuenzel, S., & Halliday, S. V. 2008. Investigating antecedents and consequences of brand identification. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 17 (5): 293–304.

Kunda, Z. 1990. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108 (3): 480–498.

Lam, D. 2007. Cultural influence on proneness to brand loyalty. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 19 (3): 7–21.

Lancaster, K. J. 1966. A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74 (2): 132–157.

Levinger, G. 1979. Toward the analysis of close relationships. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16 (6): 510–544.

Lievens, F., & Highhouse, S. 2003. The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company's attractiveness as an employer. Personnel Psychology, 56 (1): 75–102.

Lindsay, C. A., Marks, E., & Gorlow, L. 1967. The Herzberg theory: A critique and reformulation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 51 (4): 330–339.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. 1992. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13 (2): 103–123.

Marin, L., & Ruiz, S. 2007. “I need you too!” Corporate identity attractiveness for consumers and the role of social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 71 (3): 245–260.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. 1991. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98 (2): 224–253.

McFadden, D. 1986. The choice theory approach to market research. Marketing Science, 5 (4): 275–297.

Mittal, B. 2006. I, me, and mine: How products become consumers’ extended selves. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 5 (6): 550–562.

Moore, W. L., & Lehmann, D. R. 1980. Individual differences in search behavior for a non-durable. Journal of Consumer Research, 7 (3): 296–307.

Moorman, R. J., & Blakely, G. L. 1995. Individualism–collectivism as an individual difference predictor of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16 (2): 127–142.

Netemeyer, R. G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., Ricks, J., & Wirth, F. 2004. Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 57 (2): 209–224.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. 2001. Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108 (2): 291–310.

Park, C. W., Jaworski, B. J., & MacInnis, D. J. 1986. Strategic brand concept-image management. Journal of Marketing, 50 (4): 135–145.

Patterson, P. G., Cowley, E., & Prasongsukarn, K. 2006. Service failure recovery: The moderating impact of individual-level cultural value orientation on perceptions of justice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23 (3): 263–277.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5): 879–903.

Pratt, M. G. 1998. To be or not to be: Central questions in organizational identification. In D. Whetten & P. C. Godfrey (Eds), Identity in organizations: Building theory through conversations: 171–207. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. 2002. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Roth, M. S. 1995. The effects of culture and socioeconomics on the performance of global brand image strategies. Journal of Marketing Research, 32 (2): 163–175.

Schneider, B. 1987. The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40 (3): 437–453.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. 2001. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38 (2): 225–243.

Sheth, J. N., & Parvatiyar, A. 1995. Relationship marketing in consumer markets: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (4): 255–271.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. 2010. Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13 (3): 456–476.

Sirgy, M. J. 1982. Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (3): 287–300.

Sirgy, M. J., Johar, J. S., Samli, A. C., & Claiborne, C. B. 1991. Self-congruity versus functional congruity: Predictors of consumer behavior. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 19 (4): 363–375.

Solomon, M. R. 1983. The role of products as social stimuli: A symbolic interactionism perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 10 (3): 319–329.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., & Baumgartner, H. 1998. Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25 (1): 78–90.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., Hofstede, F., & Wedel, M. 1999. A cross-national investigation into the individual and national cultural antecedents of consumer innovativeness. Journal of Marketing, 63 (2): 55–69.

Stryker, S. 1968. Identity salience and role performance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and Family, 30 (4): 558–564.

Tajfel, H. 1982. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33: 1–39.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. 1979. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds), Psychology of intergroup relations: 7–24. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall.

Tesser, A. 2003. Self-evaluation. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds), Handbook of self and identity: 367–383. New York: The Guilford Press.

Tuomela, R. 1995. The importance of us: A philosophical study of basic social notions. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. 1997. Methods and data analysis for cross-cultural research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Van Dick, R., Wagner, U., Stellmacher, J., & Christ, O. 2004. The utility of a broader conceptualization of organizational identification: Which aspects really matter? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77 (2): 171–191.

Walker, B. A., & Olson, J. C. 1991. Means-end chains: Connecting products with self. Journal of Business Research, 22 (2): 111–118.

Wold, H. 1982. Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. In K. G. Jöresborg & H. Wold (Eds), Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction, Vol. 2. 1–54. Amsterdam: North Holland.

World Bank Data. 2010. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD, accessed 1 August 2010.

Young, S., & Feigin, B. 1975. Using the benefit chain for improved strategy formulation. Journal of Marketing, 39 (3): 72–74.

Zajonc, R. C., & Markus, H. 1982. Affective and cognitive factors in preferences. Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (2): 123–131.

Zeithaml, V. A. 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52 (2): 2–22.

Acknowledgements

The first author thanks his advisor, Professor Michael Ahearne, and the committee members, Assistant Professor Ye Hu, Professor Ed Blair, and Professor Bob Keller, for their useful comments during the development of this project as part of his dissertation. Special thanks to Professor C. B. Bhattacharya for helpful comments on an earlier version, and Professor Wynn Chin for the PLS Graph license. The authors also thank three anonymous reviewers and the Area Editor, Daniel Bello, for their guidance during the review process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by Daniel Bello, Area Editor, 20 October 2011. This paper has been with the authors for two revisions.

Appendices

APPENDIX A

Theoretical Foundations of the Symbolic–instrumental Framework

Economic roots

Economists generally view consumer choices as means to achieve maximization of functional utility (McFadden, 1986). Also, the common practice among marketing researchers is to model consumer brand choices based on product attributes and marketing mix (e.g., Guadagni & Little, 1983, and many subsequent extensions). However, according to the original multi-attribute utility theory (Lancaster, 1966), consumer utility includes not only a brand's functional attributes but also its sociopsychological attributes. Similarly, McFadden (1986: 284) posits that it is necessary to incorporate psychometric data in choice models, because these factors also shape the utility function. Surprisingly, only recently has research on choice models revived the need to incorporate softer, non-product-related attributes, such as customers’ attitudes and perceptions, into models of brand choice and brand switching (e.g., Ashok, Dillon, & Yuan, 2002; Erdem et al., 2006). This research, however, treats functional utility (corresponding to the instrumental driver in Katz's, 1960, conceptualization) and other utilities as additive rather than interactive. Note that Katz (1960) uses the word “functional” to refer to all the functions an attitude serves.

Consumer Psychology Roots

In psychology, Katz (1960) posits that an attitude can serve various functions. Two important functions that have received the most attention in marketing research are the symbolic and instrumental functions. However, our survey of the literature reveals a multitude of perspectives of how these drivers are linked together.

The linear, sequential perspective

Walker and Olson (1991) use the means–end chain goal to theorize that product knowledge affects self-knowledge linearly. In other words, they treat the self as the end in the means–end relationship. This perspective is also consistent with Young and Feigin’s (1975) “grey benefit chain,” which links product attributes to benefits and, ultimately, to emotional payoff. Sirgy and colleagues (1991) treat self–brand congruity (a symbolic construct) as an antecedent to functional congruity (an instrumental construct). From this perspective, self–brand congruity as a cognitive scheme at higher levels in the cognitive hierarchy is more accessible, and is likely to be processed before concrete schemes, such as functional congruity. Thus it follows that symbolic variables may bias perceptions of instrumental variables. Note, however, that Sirgy and colleagues find that the bias produced by top-down thinking is only moderate. Nevertheless, their perspective, which goes from abstract cognition to more specific cognition, is in contrast with Walker and Olson’s (1991) means–end chain model.

The independent, dual-drivers perspective

The independent, dual-drivers perspective originates from the influential work of Gardner and Levy (1955). Through qualitative research, they demonstrate (p. 39) that “products and brands have interwoven sets of characteristics and are complexly evaluated by consumers.” In Keller's (2008) customer-based brand equity pyramid, brand performance and brand imagery are two key components of brand meanings. Similarly, Mittal (2006) contends that possessions become the extended self in two ways: (1) they become instrumental because of their functional benefits; and (2) they become identity implementing, because they enhance self-expression through self–brand congruity. In line with this dual-driver perspective, Brown and Dacin (1997) show that the association between corporate ability (i.e., capability for producing products) and corporate social responsibility can have different effects on consumer responses to products. Homburg, Wieseke, and Hoyer (2009) propose the social identity perspective as an alternative to the traditional satisfaction-based service–profit chain, but do not examine the interaction between customer satisfaction and customer–company identification. Several empirical studies based on social identity theory have also hinted at the differential effects of the instrumental component (e.g., customer satisfaction with functional attributes) and the symbolic component (e.g., company prestige) on customer identification with companies and nonprofit organizations (Ahearne et al., 2005; Arnett et al., 2003; Bhattacharya, Rao, & Glynn, 1995; Donavan et al., 2006; Kuenzel & Halliday, 2008). Other research has also treated the symbolic and instrumental components of people's attitude and behavior as drivers that function independently (e.g., Lievens & Highhouse, 2003).

Conceptually, the dual-drivers perspective is consistent with hygiene theory (Herzberg, 1966), which contends that individual needs can be classified into two independent categories: (1) basic or hygiene needs, and (2) growth or higher-order needs. In other words, factors that drive dissatisfaction are not the same as satisfiers. From the means–end model we have just discussed, we can infer that instrumental drivers are lower-order hygienes, and symbolic drivers are higher-order motivators. In fact, Agustin and Singh (2005) view transactional satisfaction (which is highly correlated with perceived quality) as a lower-order need. If the instrumental and symbolic drivers are processed independently, the prediction is that the interaction between them in driving consumer brand attitude and brand-related behavior will not be statistically significant. Herzberg's theory is not without controversy (Bockman, 1971). In Lindsay, Marks, and Gorlow’s (1967) survey of the literature, they found that empirical research that relies on the theory produced mixed results. They revised Herzberg's theory, and found a positive interaction between hygiene factors and growth motivators in predicting job satisfaction.

The symbolic–instrumental interactive perspective that we propose reconciles the existing perspectives. First, it takes into consideration both symbolic and instrumental drivers of consumer–brand relationship correlates. Second, it allows for the linear sequential flowing from functional means (e.g., perceived quality) to symbolic ends (e.g., CBI). Third, it complements Sirgy and colleagues’ (1991) perspective by hypothesizing that the bottom-up process that Walker and Olson (1991) propose is as important as the top-down bias that self–brand congruity exerts on functional congruity. In other words, our interactive perspective conceptualizes the bias that Sirgy and colleagues (1991) mentioned as a mutually compensatory process between instrumental and symbolic drivers.

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX C

APPENDIX D

Analytical Notes

Exploratory factor analysis and measurement invariance

Consistent with Van de Vijver and Leung’s (1997) work, the preliminary analyses began with an exploratory factor analysis to explore across countries, which included the item characteristics, item-to-total correlations across the measuring items of each construct across countries, and factor loading pattern of all items across all constructs. After we dropped five cultural orientation items (see Appendix C), the final set of scale items yielded the hypothesized factor structure across countries, and none of the items cross-loaded heavily onto other unintended factors. Therefore we proceeded with multigroup confirmatory factor analyses to test measurement invariance before testing the structural model (Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998). Because PLS estimation does not provide a fit index for the models that allows for testing measurement invariance, and the structural equation modeling estimation does not allow for a measurement invariance test of formative constructs, we specified CBI as a second-order reflective construct (instead of a second-order formative construct) and used the fit index of the full structural equation modeling as a proxy. The configural invariance model in which all loadings were freely estimated yielded good fit (χ2(4590)=15,411.25, comparative fit index [CFI]=0.918, Tucker–Lewis index [TLI]=0.906, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.02, Akaike information criterion [AIC]=17,571.25, and Browne–Cudec criterion [BCC]=17,759.08). In multiple-group analyses, the BCC imposes a slightly greater penalty than AIC for model complexity. Because the Bayes information criterion is normally reported only for a single-group analysis, we do not report it here. All factor loadings were highly significant across all 15 countries, and most of the standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.60. The full metric invariance model in which all the factor loadings were constrained to be invariant across countries also yielded good fit (χ2(4856)=16,175.91, CFI=0.915, TLI=0.907, RMSEA=0.02, AIC=17803.91, and BCC=17,945.48). Although the increase in chi-square is significant (Δχ2(266)=764.66, p<0.00), the alternative fit indexes showed only minimal changes. Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998) recommend that, in comparing model fit, researchers should not rely exclusively on the chi-square difference test, because of its sensitivity to sample size, and that other fit indexes such as CFI, TLI, and AIC should also be used. Using this heuristic, we concluded that cross-national invariance was supported. Then, we specified a main-effects-only structural model in PLS to extract latent scores for each country. We create interactions of these latent scores to test the model with interactions (Chin, 1998).

Discriminant validity

Table 1 shows that the square of the zero-order correlation between any two constructs is smaller than the average variance extracted by the measurement items of the corresponding constructs, demonstrating discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). We also tested the discriminant validity of the focal constructs. Because there is no procedure for testing discriminant validity between a reflective construct and a formative construct, we model CBI as a reflective construct, and use the result of that model as a proxy for discriminant validity. The comparison of the AVE and the square of pairwise correlation suggests that discriminant validity was established. The models in which the correlations between the latent constructs were constrained to unity also yielded significantly worse fits, providing evidence of discriminant validity (for the focal pair of constructs, CBI-perceived quality, the change in model fit is Δχ2(1)=48.5, p<0.01).

Common method biases

The conceptual framework of this study has two formative constructs (CBI, self–brand incongruity), and is focused primarily on interaction effects. Prior research has shown that, statistically, interaction effects cannot be artificially created by common method biases (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, 2010). Conceptually, consumers who fill out the survey are much less likely to be able to guess the interaction effects that we test. Podsakoff et al. (2003: 900) recommend that “when formative-indicator constructs are an integral part of a study, researchers must be even more careful than normal in designing their research because procedural controls are likely to be the most effective way to control common measurement biases.” Consistent with this recommendation, we designed our survey such that it included a variety of question types and response formats, including Venn diagram and Likert scales of different lengths; the self–brand incongruity score is a Euclidean score calculated from a number of questions. The items of the focal construct of CBI appeared in three different sections in the survey, some of which appeared after we asked consumers about the dependent variables. These procedural remedies help with reducing common method biases (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

APPENDIX E

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, S., Ahearne, M. & Schillewaert, N. A multinational examination of the symbolic–instrumental framework of consumer–brand identification. J Int Bus Stud 43, 306–331 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.54

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.54