Abstract

Studying knowledge strategy empirically requires that specific strategies be operationalized. In this paper, two existing knowledge strategy typologies (the Bierly & Chakrabarti typology of Loners, Explorers, Exploiters and Innovators and the von Krogh, Nonaka & Aben typology of Leveraging, Expanding, Appropriating, and Probing) are compared and mapped onto knowledge strategy dimensions, generating a set of eight ideal knowledge strategy profiles. These profiles are then applied to eight case studies, to develop a better understanding of knowledge strategies by investigating how the two typologies are related. Results suggest that a hierarchy exists between the two knowledge strategy typologies: the Bierly & Chakrabarti typology operates at the grand strategy level, while the von Krogh et al. typology works at the operational strategy level. Findings also suggest that consistent portfolios of operational knowledge strategies can support an organization's grand knowledge strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the knowledge-based economy, managers focus on issues of knowledge capital over more traditional assets and on the capability of their organizations to harness these knowledge assets. Knowledge can be viewed as a key strategic resource to be acquired, manipulated, and applied, and thereby produce competitive advantage (Zack, 2003). In this environment, ‘the sustainable competitive advantage of business firms flows from the creation, ownership, protection, and use of difficult-to-imitate commercial and industrial knowledge assets’ (Teece, 2000, p. 35). It may well be intellectual capital management challenges – not financial management issues – which ultimately limit firm growth and success (Soo et al., 2002; Macpherson & Holt, 2007).

A distinguishing feature of the knowledge-based economy is the ability of a firm to take advantage of its knowledge assets through the capabilities of building, protecting, transferring, and integrating knowledge (Teece, 2000; Baskerville & Dulipovici, 2006). Because the context- and process-specific knowledge that tends to accumulate in a firm's organizational routines is difficult to imitate, benefits from the development of this knowledge can accrue to the firm (Zack, 1999). As companies benefit from managing this knowledge proactively, it is possible to conceptualize knowledge strategy independent of other firm strategies (von Krogh et al., 2001).

While an organization's competitive position creates a requirement for new knowledge, its existing knowledge resources simultaneously create opportunities and constraints; hence, it is important to generate strategies to coordinate these competing demands (Zack, 1999). Realized strategies are those reflected in decision making, resource allocation, and activities actually conducted by the organization (Mintzberg, 1978). A knowledge strategy can be viewed as ‘the overall approach an organization intends to take to align its knowledge resources and capabilities to the intellectual requirements of its [business] strategy’ (Zack, 1999, p. 135). As research interest in knowledge strategies expanded, researchers independently developed knowledge strategy types and dimensions to describe emergent use of knowledge strategies by firms. Now, however, the knowledge strategy domain has matured to the point where comparison of existing knowledge strategies is viable, similar to the comparison of business strategy typologies two decades ago (Segev, 1989). The aim of this paper is to develop a better understanding of knowledge strategies by investigating how two knowledge strategy typologies are related.

The remainder of this paper is composed as follows. The next section describes the theoretical background for the study by identifying the two knowledge strategy typologies and developing a framework of knowledge strategy dimensions. The following two sections describe the case study research method, and the analysis and results. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications for practice and future research.

Theoretical background

This study is designed to explore the relationship between two knowledge strategy typologies through their links to a set of underlying dimensions of knowledge strategy. In this section, we first discuss the difference between knowledge management (KM) strategy and knowledge strategy, then we present two knowledge strategy typologies and finally we introduce the knowledge strategy dimensions.

Knowledge management strategy vs knowledge strategy

Knowledge strategy has been identified as one of three meanings used for KM strategy, with a focus on knowledge-based competitive advantage vs either an approach to KM or the implementation of KM (Saito et al., 2007). KM refers to the portfolio of procedures and techniques used to get the most from a firm's knowledge assets (Teece, 2000). While KM strategy deals with structural and technical management issues, knowledge strategy deals with business outcomes and support for competitive advantage.

For example, Zack's (1999) knowledge strategies of exploration and exploitation focus on the application of knowledge within the firm, while Hansen et al.'s (1999) KM strategies of codification and personalization focus on the structuring of knowledge within the firm. Earl's (2001) KM strategy taxonomy supports this differentiation, as the focus and aim of each of the seven schools revolves around the management of knowledge rather than its application for competitive purposes. In contrast, Casselman & Samson (2007) identify seven components of knowledge strategy that relate to generating competitive advantage: internal organization, measurement and reward, boundaries, knowledge advantage, protection, disaggregation, and investment intensity. While the importance of KM strategy is acknowledged, this paper focuses exclusively on knowledge strategy.

Knowledge strategy typologies

While there are typologies that describe knowledge capabilities (Gold et al., 2001), schools of KM (Earl, 2001), and types of knowledge (Alavi & Leidner, 2001), there are few studies that describe knowledge strategy. Two well-received knowledge strategy typologies are compared in this paper. The first is a set of generic knowledge strategies proposed by Bierly & Chakrabarti (1996), who, while extending earlier organizational learning work (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; March, 1991), were the first to identify this set as a coherent package. The second is a set of strategies proposed by von Krogh et al. (2001), who examined the firm's orientation and focused on strategy development and application.

In the first knowledge strategy typology, Bierly & Chakrabarti (1996) conducted a cluster analysis of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, based on four knowledge strategy dimensions: knowledge source, radicalness of learning, speed of learning, and scope (breadth in the original study) of knowledge. Their results identified four distinct generic knowledge strategy types among firms: loners, explorers, exploiters, and innovators. A loner is an isolate in terms of knowledge. Loners are ineffective, with higher R&D expenditure ratios, slow technology cycles, and low knowledge dispersion. An explorer is a creator or acquirer of the knowledge required to be competitive in its strategic position. Explorers have high levels of radicalness but are similar to other groups in other characteristics. An exploiter has capabilities that exceed the requirements of its competitive position, allowing it to use its knowledge to deepen or broaden its position. Exploiters have low R&D expenditure and broad but shallow knowledge bases. An innovator integrates the best characteristics of an explorer and an exploiter. Innovators are the most aggressive and fastest learners, combining internal, external, radical, and incremental learning.

In the second knowledge strategy typology, von Krogh et al. (2001) identified two core knowledge dimensions – knowledge creation and knowledge transfer – and examined their impact on a business unit of Unilever. Integration of these two dimensions resulted in four strategy types: leveraging, expanding, appropriating, and probing (von Krogh et al., 2001). Leveraging can be oriented towards achieving efficiency in operations and ensuring that the firm internally transfers existing knowledge from various knowledge domains. Leveraging is an effective strategy because to acquire similar knowledge, competitors have to engage in similar experiences (Leonard-Barton, 1995). Expanding implies increasing the scope and depth of knowledge domains by refining what is known and by bringing in additional expertise relevant for knowledge creation. Knowledge-based competitive advantage is sustainable through expansion because the more a firm already knows, the more it can learn (Zack, 1999). Appropriating is predominantly oriented externally on knowledge domains that do not already exist in the firm, capturing knowledge from external partners. The main vehicles for inter-organizational appropriation are strategic alliances, collaborations, and joint ventures (Powell et al., 1996). The probing strategy gives teams the responsibility to build new knowledge domains from scratch, identifying individuals interested in contributing to innovation as the ‘creative destroyers’ of the current organization (Boisot, 1995). New knowledge is created outside of the firm's current knowledge domain and then brought into the organization.

Knowledge strategy dimensions

To compare the two typologies, each knowledge strategy type is described in a synthesis of the underlying dimensions of both knowledge strategy typologies. Specifically, knowledge source, radicalness of learning, speed of learning, and scope of knowledge are drawn from Bierly & Chakrabarti (1996) and knowledge creation and knowledge transfer are taken from von Krogh et al. (2001). By examining all eight types through each dimension used to create both typologies, a more detailed understanding of their relationships can be established. In addition, as knowledge strategy guides resource allocation (Zack, 1999), these dimensions are representative of organizational decisions and tendencies regarding the application of knowledge assets.

Knowledge source

Primary knowledge source refers to where the organization gets its knowledge from (Zack, 1999). Internal learning occurs when new knowledge is generated and distributed by members within the organization; external learning occurs when organizational members bring in knowledge from outside the firm (Bierly & Chakrabarti, 1996). Internally generated knowledge tends to be unique, specific, and tacitly held, and hence, difficult to imitate; externally generated knowledge tends to be more abstract, packaged, and widely available, and hence, more easily imitated (Zack, 1999). Knowledge source is divided into internal and external aspects to address the fact that some firms balance internal and external learning.

Knowledge process

Organizational knowledge creation is ‘the process of making available and amplifying knowledge created in individuals as well as crystallizing and connecting it with an organization's knowledge system’ (Nonaka et al., 2006, p. 1179). Primary knowledge process refers to the core knowledge processes of creation and transfer (von Krogh et al., 2001). The specific focus of the organization may be on the creation of new knowledge or the application of existing knowledge and the degree of balance between the two (Zack, 2003). Knowledge process is divided into creation, and transfer, reflecting the tension between the two aspects and the firm's ability to potentially master both.

Knowledge focus

How an organization uses knowledge defines its strategy in terms of its knowledge focus (Zack, 1999). One extreme is exploration, where the firm focuses on creating or acquiring new knowledge in order to stay competitive. The other extreme is exploitation, where the organization uses slack knowledge resources to further develop a competitive position. There is a natural tension in an organization between assimilating new knowledge through exploration and using existing knowledge through exploitation (Crossan et al., 1999). However, these two aspects are not mutually exclusive, as certain knowledge areas may be exploited while others are explored (Zack, 1999).

Radicalness of learning

Learning can be defined as ‘a relatively permanent change in knowledge... produced by experience’ (Weiss, 1990, p. 172). Radical learning challenges the basic assumptions of the organization, whereas incremental learning gradually expands the firm's knowledge base (Bierly & Chakrabarti, 1996). In general, the concept of absorptive capacity suggests that to understand, evaluate, and use outside knowledge, the firm must have a level of prior related knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). This may limit the ultimate degree of radicalness of the ideas an organization can assimilate, as an organization must first recognize the potential value of new knowledge before it can be considered to be ‘learned’ (Huber, 1991).

Speed of learning

Speed of learning in competitive markets is important because the most competitive knowledge position involves knowledge that is codified and most easily – but yet to be – diffused (Boisot, 1995). Faster learning extends the gap between a firm's ability to replicate its knowledge and its competitors’ ability to imitate it. Slower rates of learning, however, have the benefit of letting a firm evaluate knowledge positions in the market, allow complementary streams of knowledge to develop together, and integrate knowledge more effectively once environmental uncertainty has been reduced (Bierly & Chakrabarti, 1996).

Scope of knowledge

Breadth reflects the extent to which a firm's knowledge is specialized or generalized, whereas depth refers to the degree to which a firm develops a specific domain of knowledge (Bierly & Chakrabarti, 1996). A narrow focus adopted to develop a deep knowledge base may lead to the development of core competencies; a wide focus adopted to develop a broad knowledge base may lead to a combination of related technologies and knowledge. A firm's absorptive capacity is based upon its scope of prior knowledge in the domain (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Maintaining too narrow and deep a knowledge base may prevent the recognition of new knowledge outside of this specialized area; however, maintaining too broad and shallow a knowledge base may leave the firm without the requisite understanding to assimilate and synthesize that same knowledge (Garud & Nayyar, 1994). As the scope of knowledge can be both broad and deep, these dimensions have breadth and depth aspects that are not mutually exclusive.

Research method

In this section, we describe our approach, why we chose the case study method, the interview and data collection process, and how analysis was conducted at both individual and cross-case levels.

Research approach

As the typologies and their underlying dimensions were known and the research objective was to identify the relationships between them, the research was approached as theory-building using multiple comparative cases (Dul & Hak, 2008). To identify the relationship between the two knowledge strategy typologies, the study proceeded through three steps: first, previous research was consulted to select the dimensions to evaluate as part of the research framework; second, based on the body of literature, an interview guide was created to capture each underlying dimension and type; and third, interviews were conducted at the participant sites, followed by a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the data.

Case study method

The case study has been suggested as an appropriate method to answer research questions relating to the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ of a phenomenon (Yin, 1994). Cases can be very persuasive as they provide rich context for the discussion of theory (Siggelkow, 2007). The case study method has been cited as effective in generating theory early in the research of a new topic (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1994). Our research is a multiple case study following guidelines and standards established for case study research (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Gibbert et al., 2008). The unit of analysis is the firm. The population is medium-sized enterprises in the business and educational services sectors in Canada. Given the focus of the study on knowledge strategies, these industries were selected for the high knowledge intensity of the firms operating in them.

Case studies can be assessed on three major types of validity – internal, construct, and external – and reliability (Yin, 1994). Internal validity was enhanced through the use of a pattern matching strategy within and between cases, and through the implementation of natural controls through multiple cases in a set of knowledge-intensive industries within the same country. Construct validity was addressed through the chain of evidence that a qualitative package such as NVivo 7 provides, the review of transcripts by informants, and the use of multiple sources of evidence including interviews and documents. External validity was enhanced through the use of cross-case analysis and through the confirmation that theory fit across the eight case sites. Reliability was aided by the production of interview documentation and the organization of documentary evidence through the structures provided by NVivo 7.

Interview and data collection process

At each of the eight case sites, interviews were conducted with the CEO and managers responsible for a variety of functional areas including operations, information systems, finance, human resources, and marketing. Depending on the size of the organization, the number of interviews ranged from three and seven per site. Interviews were semi-structured and based upon an interview guide. The interview questions were derived from the descriptions of the knowledge dimensions from the literature. The questions were pilot-tested on two doctoral candidates and one faculty member prior to conducting the interviews. Thirty-eight interviews lasting between 30 and 90 min were conducted, resulting in over 700 pages of typed transcripts. Participants were sent copies of their transcripts to provide them with the opportunity to clarify or expand discussion points.

In addition to interview data, we collected archival data, either provided directly by the organization or from public sources such as firm websites. All transcripts were coded using NVivo 7 software based on a coding guide derived from the construct list. It was anticipated that, with these eight case sites, sufficient depth of data would be collected to fully explore the knowledge strategy dimensions and achieve theoretical saturation – what Glaser & Strauss (1967) identify as the point at which there is minimal incremental learning from each case.

Analysis at individual and cross-case levels

Analysis was conducted at both individual case and cross-case levels. For individual cases, a case summary was written providing key observations on each knowledge dimension and typology (Yin, 1994). The last step in the individual case analysis, and the first step in the cross-case analysis, was to convert the thick description into a single level of performance (low, medium, or high) for each dimension of knowledge strategy (Miles & Huberman, 1984). This was done individually and then adjusted in comparison with the other firms at the cross-case level. Using the interview data and case documents, the cross-case analysis was largely based on examining the linkages between the knowledge strategy dimensions and typologies.

Results

The analysis and associated results are presented in three parts. First, each case site is described and then analyzed qualitatively in terms of the two typologies. Second, the qualitative data from the case studies is quantified and analyzed using the profile deviation approach. Third, the results of the qualitative and quantitative analyses are integrated and illustrated using case examples.

Qualitative analysis

Analysis was conducted at the individual case and cross-case levels. For individual cases, a case summary was written providing key observations on each knowledge dimension and typology. The majority of the cross-case analysis was based on examining the linkages between the knowledge strategy dimensions and typologies, using the interview data and case documents.

While they were drawn from different industrial sectors and regions across Canada, the eight case sites were linked by their reliance on knowledge and their need to strategically manage it. As seen in Table 1, the case sites varied widely in structure and issues faced, but closer examination showed some degree of commonality. The organizations pertaining to correctional education (CorrEd), construction engineering (ConEng), and manufacturing services (ManuServ) were each focused on aggressive growth, while the public library (PubLib), public education (PubEd), and legal services (LegServ) were restricted by conservative cultures. Each organization faced different internal and external pressures that shaped their decisions, such as imposed changes in environment for development education (DevEd) and distance education (DistEd), and internal amalgamations for LegServ and PubEd. In spite of differences in environments and approaches, each organization tried to provide the best service possible to its clients considering the constraints and opportunities faced. The knowledge strategies of the firms were developed as a response to these constraints and opportunities.

The first theory lens used to examine the cases was that of Bierly & Chakrabarti, focusing on the organizations’ affinity to exploiter, explorer, innovator, or loner types. As depicted in Table 2, the majority of firms – CorrEd, ConEng, LegServ, and PubEd – tended towards exploitation of current knowledge. DevEd proved to be an explorer through its aggressive seeking of new knowledge for the organization. PubLib and ManuServ balanced these extremes, exploiting existing knowledge to generate further value from it while developing new knowledge. Only DistEd appeared to be a loner as it faced numerous obstacles to the creation of new knowledge and the diffusion of existing knowledge.

The second theory lens used to examine the case studies was that of von Krogh et al., focusing on the firms’ application of leveraging, expanding, appropriating, and probing strategies. As shown in Table 3, the leveraging strategy proved very important to CorrEd, ConEng, LegServ, and PubEd, as each of these firms was highly reliant on the distribution of knowledge. The probing strategy was very important to DevEd, PubLib, and ManuServ, who were constantly seeking new knowledge to apply. Appropriation proved to be an important strategy for ConEng, DevEd, DistEd, and PubLib, each of which had strong partnerships and networks. Finally, the expanding strategy was very useful for CorrEd, ConEng, DevEd, PubLib, and PubEd, each of whom invested in further developing existing knowledge.

Quantitative analysis

Having identified what knowledge strategies were in use by firms through qualitative analysis and with a wealth of data on the individual firms and their knowledge strategies, a more quantitative approach was used to determine the relationships between the strategies.

The relationships between the dimensions, types, and firms were determined through an investigation of their degree of fit. Venkatraman (1989) categorized the concept of fit in a classificatory framework with axes of specificity and anchoring, resulting in six interpretations of the concept. Given that each typology and firm is assessed on ten dimensions of knowledge strategy, the profile deviation approach between observed and theoretical configurations is appropriate due to the complexity of paths generated by the interactions and moderating effects found in a fully-specified multivariate model (Tosi & Slocum, 1984; Drazin & Van de Ven, 1985; Gresov, 1989; Sabherwal & Chan, 2001). Profile deviation, which is defined as the degree of adherence to an externally specified profile, is criterion specific, allowing direct comparison between the firm and its idealized profile, but, being low in specificity, it does not require a precise functional form of the fit relationship (Venkatraman, 1989).

The first step in the quantitative analysis was to create theory-based expectations of cross mapping between the typologies. The approach selected was to identify the relative importance of a von Krogh et al. strategy to an idealized firm choosing one of Bierly & Chakrabarti's strategies. Knowledge source, process, focus, and breadth were dichotomized into two aspects each to reflect that they do not exist on a single continuum, but rather can have simultaneous high or low values on each factor. This resulted in a total of ten dimensions being identified. Based on a review of the literature and the several dichotomized dimensions, we independently cross-coded the ten dimensions and eight types and resolved any differences in classification, resulting in Table 4. Appendix A summarizes the literature guiding each decision.

Based on the theoretical profiles in Table 4, ideal values were set for each dimension to 1, 0, and −1 for high, medium, and low, respectively. The Euclidean distance between strategies was calculated and an ideal profile determined, as shown in Table 5. The distance between typologies was calculated by taking the square root of the sum of squares of the differences between the numeric values of two strategy profiles for each of the ten dimensions.

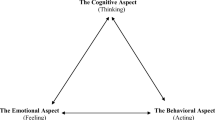

In the top half of Figure 1, von Krogh et al.'s strategies are presented in descending rank order of importance, and the size of the font is indicative of the Euclidean distance from the Bierly & Chakrabarti strategy. For example, the literature suggests that, while leveraging is the most important strategy for loners relative to the other strategies, in absolute terms it is still not particularly close to the loner strategy, which is generally unfocused; hence, it has a medium-sized font. In contrast, the intentional selection of a leveraging strategy by an exploiter is reflected in both the relative preferences, as indicated by being first in rank order, and in absolute proximity to the exploiter strategy, as indicated by the large font. In the bottom half of Figure 1, the mapping is reversed so that the Bierly & Chakrabarti strategies are presented in descending rank order of importance, and the size of the font is indicative of the Euclidean distance from the von Krogh et al. strategy.

The second step in the quantitative analysis was to identify the knowledge strategy profile of each firm based upon the narrative description from the case studies. Each interview and case summary was reviewed for indicators that matched the strategy dimensions based on interviewee responses. Perceptions of interviewees were considered acceptable measures, as prior research has shown that managerial assessments of performance are closely correlated to objective performance indicators (Dess & Robinson, 1984). As shown in Table 6, firms were categorized as low, medium, or high individually for each dimension and then compared at a cross-case level to confirm consistency. Appendix B identifies key observations on which each decision was based.

The third and final step of the quantitative analysis was to take the firm profiles in Table 6 and convert them to numerical values, using the same 1, 0, and −1 classification for high, medium, and low levels used for the ideal profiles. The Euclidean distance between each firm's profiles and the ideal profiles for both of the two knowledge strategy typologies was calculated. Each firm was assigned a classification under the Bierly & Chakrabarti typology based upon the closest proximity, and then the von Krogh et al. strategies were rank ordered and sized in the same manner as done for the ideal profiles: this is calculated in Table 7 and illustrated in Figure 2.

Integration of qualitative and quantitative results

Comparing firms’ actual profiles to their corresponding ideal profiles, seven of the eight firms concur with the expected rank order. DistEd's mismatched profile as a loner is the sole exception, with neither qualitative nor quantitative results supporting the ideal type, though at the dimensional level DistEd had the lowest ratings amongst the sample, as would be expected. The ideal loner is an isolate, with a low reliance on the appropriating strategy. While the other three strategies are in the anticipated order for DistEd, appropriation jumped from least to most heavily relied upon. It should be noted that the importance of an appropriating strategy was a conscious decision as it represented the firm's attempts to avoid the resource constraints that hampered the effectiveness of the organization. Hence, while DistEd has the strategy dimensions that most closely align its realized strategy with the loner profile, the intended strategy may be that of an exploiter or innovator as seen in its choice of strategies to deliberately enact (Mintzberg, 1978).

Conversely, all four firms identified as exploiters demonstrated the expected reliance on transfer processes and exploitation focus, as well as an affinity for leveraging and an avoidance of probing strategies. For example, CorrEd worked in the correctional services education domain and based their value proposition on exploiting a combination of education delivery and corrections procedural knowledge. Significant characteristics of the environment were dispersion, and isolation, making investment in a strong leveraging strategy appropriate for the firm and a good match for the exploiter strategy. ConEng's focus on codification and reuse of explicit knowledge was similarly related to a strong leveraging strategy, through the implementation of their document management system and to the expansion of knowledge into incrementally different domains. As noted by their CEO, ‘if we’re going to be innovative we should try to be innovative to improve our core competencies, not jump out of the field and try to do something else completely different’.

Two firms emerged as innovators from the qualitative and quantitative analyses. ManuServ chose an innovator strategy focused on the development of new knowledge in one area of operations and then export of that knowledge to other divisions and work sites, all based on the development of a common knowledge core. The associated probing strategy of the firm was captured by the CEO who noted, ‘the reality is that I wanted that business…. We didn’t necessarily have an understanding. We assembled a team. Each of us took a role in the research and understanding of it’. Similarly, PubLib's vision of becoming a community information hub pushed them onto an innovator's path, simultaneously protecting and revitalizing the knowledge in their traditional services domain while developing new knowledge to serve e-services and cultural domains. This innovative focus was found in the probing of new digital information management techniques and the expanding of knowledge in the core area of provision of information. These firms both showed the expected high ratings on external source of knowledge, the creation process, an exploration focus, radicalness of learning, and breadth of knowledge.

The sole explorer in the sample also supported the conceptual ideal profile, both in the qualitative and quantitative analyses, though it was close to an innovator at the dimensional level due to its ability to exploit current knowledge and its external sourcing of knowledge through partners. The CEO of DevEd commented that ‘research, training, innovation, connecting and rewarding are all part of what we do and need to do more of to continue to be on the cutting edge of our field’, which was supported by this firm's constant seeking of new knowledge. The importance of the probing strategy to DevEd could be seen in the development of a Canadian capability to deal with a behavioural disorder that could previously only be treated in the U.S. Appropriation was another major strategy of the organization: as the CEO noted, ‘all of these collaborative ventures added to our knowledge base and added to our reputation as an agency interested in partnerships and the creation of new ideas and ways of doing things’.

Discussion

An important implication of the analysis can be found in the conceptualization of the relationship between the typologies. The relationship between the two knowledge strategy typologies can be envisioned by considering how to group each with the other. Grouping the four Bierly & Chakrabarti types under each von Krogh et al. category would be phrased in terms of expected employment. For example, under the leveraging strategy category, one would expect to see leveraging strategies employed most frequently in exploiters and least frequently in explorers. Grouping the four von Krogh et al. categories under the Bierly & Chakrabarti typology would be phrased in terms of anticipated use. For example, in the explorer category, one would anticipate frequent use of probing strategies but rare use of leveraging strategies. Expressed differently, it appears that an innovating strategy can be made up of a portfolio weighted towards probing and appropriating strategies, but a probing strategy cannot be made up of a portfolio weighted towards explorer and innovator strategies.

This conceptualization leads to the proposal of a hierarchical relationship between the strategy typologies. Strategy can be defined as a pattern in a stream of decisions (Mintzberg, 1978). Both typologies meet this definition of strategy, but there may be different levels of strategy at which they operate. Business literature differentiates between corporate, business unit, and functional strategies (Chandler, 1962; Ansoff, 1965; Porter, 1980). These two typologies address knowledge management at the business unit level. However, within the business unit level, there are two categories of strategy – ‘grand strategy’, and ‘operational strategy’: grand strategy refers to the overarching goals that guide all business unit actions and operational strategy refers to the patterns of application of resources to achieve these goals (Glueck, 1976; Hitt et al., 1982; Pearce, 1982). Just as grand strategy is predominant and of long duration, the Bierly & Chakrabarti typology is of enduring strategy types that change only infrequently. The von Krogh et al. typology meets the criteria for operational strategy, in that a portfolio of strategies can be used either simultaneously or sequentially to develop different areas of knowledge within the organization to achieve the grand strategy. While the Bierly & Chakrabarti typology is as an example of higher order grand knowledge strategy, the von Krogh et al. typology is an example of a lower order operational knowledge strategy. They are, therefore, complementary rather than competing typologies.

The differences between the typologies and suggested hierarchy can also be explained in terms of their assumptions regarding knowledge strategy. The von Krogh et al. (2001) definition focuses on the ‘allocation of resources’ (p. 435) whereas the Bierly & Chakrabarti (1996) definition focuses on ‘collective responses to… four strategic choices’ (p. 124). This examination of the two definitions would suggest that the latter definition leads to an organizational position and set of beliefs that guide the selection of the former strategies. Following the selection or evolution of the grand knowledge strategy, the operational knowledge strategies can be implemented sequentially or simultaneously.

The use of a sequential portfolio of knowledge strategies is best illustrated by DevEd, the behavioural support and education firm that was classified as an explorer. The decision to emphasize a particular knowledge strategy over another can lead to different outcomes and a desired cumulative effect. Faced with immediate concerns regarding possible closure of the organization, the CEO chose an initial expanding strategy through the implementation of a professional development programme to quickly reinforce the knowledge and capabilities of the organization. This was followed by an appropriating strategy to partner with external agencies to gain access to otherwise unavailable knowledge and create new opportunities. Once the organization's future was more secure, a probing strategy was used to develop unique capabilities and expand the range of services available. Throughout the changes in operational strategies, the organization's grand strategy remained focused on knowledge exploration.

The use of a simultaneous portfolio of knowledge strategies can best be illustrated by ManuServ, the business outsourcing services firm that was classified as an innovator. This firm excelled at maintaining parallel operational knowledge strategies throughout the organization in spite of its small size. In the establishment of the semi-product manufacturing capability, all four strategies were applied simultaneously. A core team was created to probe for new knowledge that was not available in the industry regarding the process and how to automate it. Individuals with experience in similar processes were hired, and the outsourcing partner's knowledge was tapped in order to appropriate knowledge for the firm. Knowledge of control system engineering was expanded into the real-time control domain. Experience in process control and work scheduling was leveraged from the manufacturing cleaning domain into the new semi-product manufacturing domain. Consistently, throughout its history and the project, this firm was focused on knowledge innovation.

Conclusions

The core finding of this study is that a hierarchy exists between two knowledge strategy typologies, where consistent portfolios of operational knowledge strategies can support a grand knowledge strategy. Each typology was classified based on underlying knowledge strategy dimensions, and the two typologies were compared on those dimensions. The ideal relationships between typologies were compared to relationships found in eight case studies, with a high degree of congruence between the theoretical ideals and empirical findings. In examining the relationships between the two typologies, both conceptually and through case studies, the hierarchy and portfolios became apparent.

Limitations

There are inherent limitations of the analysis that suggest some caution be exercised in interpreting the results. First, as noted earlier, there are no perfect matches between the firms studied and the ideal knowledge strategy profiles; however, to simplify analysis, each firm was classified into a single type in the Bierly & Chakrabarti typology. This means that while each firm was treated as a representative of a ‘pure strategy’, it exhibited characteristics of neighbouring strategies. No effort was made to discuss and test hybrid strategies in order to avoid complicating the analysis.

The second limitation is the study reliance on medium-sized enterprises in the sample. While the von Krogh et al. (2001) typology was developed in Unilever (a multinational firm employing nearly 175,000 people with world-wide revenues of 40.5 billion in 2008) and the Bierly & Chakrabarti (1996) was developed through an analysis of large firms in the pharmaceutical industry, this study was undertaken in medium-sized firms with between 100 and 1000 employees. While each of the types was represented in the sample, it is possible that the relationships are related to the organizations’ size. However, all the strategy types examined were at the business unit level: each firm in the sample can be seen as representing a single business unit, and hence, the same concepts can be applied.

Research and management implications

This study has two obvious research implications. First, the proposed hierarchical relationship between these two typologies illustrates how each can be used for different levels of analyses. Although there is no apparent dominant knowledge strategy typology in the literature (because successive papers have defined their own typologies to establish their contributions), the knowledge strategy field could benefit from the adoption of common typologies (Choi & Lee, 2002). The acceptance of these two strategy typologies at two levels and the relationship between them would promote the development of a cumulative research tradition in the knowledge strategy domain.

Second, the establishment of a common set of dimensions upon which to compare knowledge strategies could also further the development of this research tradition. The dimensions provide a rich structure in which to study knowledge strategies in firms. We advocate further exploration of the validity of these different dimensions.

For practitioners, the proposed concept of portfolios of operational knowledge strategies supporting a particular grand knowledge strategy may address issues of consistency or alignment. The identification of knowledge strategy at the grand knowledge strategy level could allow for a common view of how a firm deals with its knowledge, and focus managerial attention on creating consistent knowledge strategies for the firm. In firms with fewer resources, choices may have to be made to develop a portfolio of operational knowledge strategies that can be tailored to support a desired or existing grand knowledge strategy. This would also lead to decisions at the dimensional level that are aligned with both the operational and grand knowledge strategies. This level of understanding could be important to ensuring consistency in knowledge strategy selection within the organization and ensure that valuable effort is not wasted towards creating potentially conflicting or counter-productive knowledge strategy portfolios.

Future research

A number of future research opportunities may be available based upon these findings. First, as noted in the limitations, this study sample was limited to medium-sized enterprises; so either very small or very large firms may exhibit different portfolios of knowledge strategies. In addition, as the study was conducted at the business unit level, different units may have different grand knowledge strategies, adding to the complexity and richness of a firm's knowledge strategies.

While size of the firm is a consideration and a well-used variable of study, there are several others, including industry and sector. Additionally, there may be many antecedents and consequences of knowledge strategies, their dimensions, and their relationships that could be studied.

Finally, an issue that was neither examined nor resolved but requires future study is the relationship between knowledge strategy and business strategy. Specifically, neither the Bierly and Chakrabarti typology nor the von Krogh, Nonaka, and Aben typology have been used in studies of alignment within the firm. With the greater understanding of the knowledge strategies types developed in this paper, there is an opportunity to apply this knowledge in the wider context of aligned firm strategies.

References

Alavi M and Leidner DE (2001) Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly 25 (1), 107–136.

Ansoff HI (1965) Corporate Strategy: An Analytic Approach to Business Policy for Growth and Expansion. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Argyris C and Schön D (1978) Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Baskerville R and Dulipovici A (2006) The theoretical foundations of knowledge management. Knowledge Management Research & Practice 4 (2), 83–105.

Bierly P (1999) Development of a generic knowledge strategy typology. Journal of Business Strategies 16 (1), 1–26.

Bierly P and Chakrabarti A (1996) Generic knowledge strategies in the U.S. pharmaceutical industry. Strategic Management Journal 17 (Winter Special Issue), 123–135.

Boisot MH (1995) Is your firm a creative destroyer? Competitive learning and knowledge flows in the technological strategies of firms. Research Policy 24 (4), 489–506.

Casselman RM and Samson D (2007) Aligning knowledge strategy and knowledge capabilities. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 19 (1), 69–81.

Chandler AD (1962) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the Industrial Enterprise. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Choi B and Lee H (2002) Knowledge management strategy and its link to knowledge creation process. Expert Systems with Applications 23 (3), 173–187.

Cohen WM and Levinthal DA (1990) Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 35 (1), 128–152.

Crossan MM, Lane HW and White RE (1999) An organizational learning framework: from intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review 24 (2), 522–537.

Dess GG and Robinson Jr. RB (1984) Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: the case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal 5 (3), 265–273.

Drazin R and Van de Ven AH (1985) Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory. Administrative Science Quarterly 30 (4), 514–539.

Dul J and Hak T (2008) Case Study Methodology in Business Research. Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier, Oxford, U.K.

Earl M (2001) Knowledge management strategies: toward a taxonomy. Journal of Management Information Systems 18 (1), 215–233.

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14 (4), 532–550.

Eisenhardt KM and Graebner ME (2007) Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal 50 (1), 25–32.

Garud R and Nayyar PR (1994) Transformative capacity – continual structuring by intertemporal technology-transfer. Strategic Management Journal 15 (5), 365–385.

Gibbert M, Ruigrok W and Wicki B (2008) What passes as a rigorous case study? Strategic Management Journal 29 (13), 1465–1474.

Glaser B and Strauss A (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies of Qualitative Research. Wiedenfeld and Nicholson, London, U.K.

Glueck WF (1976) Business Policy: Strategy Formation and Management Action. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Gold AH, Malhotra A and Segars AH (2001) Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems 18 (1), 185–214.

Gresov C (1989) Exploring fit and misfit with multiple contingencies. Administrative Science Quarterly 34 (3), 431–453.

Hansen MT, Nohria N and Tierney T (1999) What's your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review 77 (2), 106–116.

Hitt MA, Ireland RD and Palia KA (1982) Industrial firms’ grand strategy and functional importance: moderating effects of technology and uncertainty. Academy of Management Journal 25 (2), 265–298.

Huber GP (1991) Organizational learning: the contributing processes and the literatures. Organization Science 2 (1), 88–115.

Kogut B and Zander U (1992) Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science 3 (3), 383–397.

Leonard-Barton D (1995) Wellsprings of Knowledge: Building and Sustaining the Sources of Innovation. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Macpherson A and Holt R (2007) Knowledge, learning and small firm growth: a systematic review of the evidence. Research Policy 36 (2), 172–192.

March JG (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science 2 (1), 71–87.

Miles MA and Huberman AM (1984) Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.

Mintzberg H (1978) Patterns in strategy formulation. Management Science 24 (9), 934–948.

Nonaka I, von Krogh G and Voelpel S (2006) Organizational knowledge creation theory: evolutionary paths and future advances. Organization Studies 27 (8), 1179–1208.

Pearce II JA (1982) Selecting among alternative grand strategies. California Management Review 24 (3), 23–31.

Porter ME (1980) Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. Free Press, New York, NY.

Powell WW, Koput KW and Smith-Doerr L (1996) Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of innovation: networks of learning in biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (1), 116–145.

Sabherwal R and Chan YE (2001) Alignment between business and IS strategies: a study of prospectors, analyzers, and defenders. Information Systems Research 12 (1), 11–33.

Saito A, Umemoto K and Ikeda M (2007) A strategy-based ontology of knowledge management technologies. Journal of Knowledge Management 11 (1), 97–114.

Segev E (1989) A systematic comparative analysis and synthesis of two business-level strategic typologies. Strategic Management Journal 10 (5), 487–505.

Siggelkow N (2007) Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal 50 (1), 20–24.

Soo C, Devinney T, Midgley D and Deering A (2002) Knowledge management: philosophy, processes, and pitfalls. California Management Review 44 (4), 129–150.

Teece DJ (2000) Strategies for managing knowledge assets. Long Range Planning 33 (1), 35–54.

Tosi Jr. HL and Slocum Jr. JW (1984) Contingency theory: some suggested directions. Journal of Management 10 (1), 9–26.

Venkatraman N (1989) The concept of fit in strategy research: toward verbal and statistical correspondence. Academy of Management Review 14 (3), 423–444.

Von Krogh G, Nonaka I and Aben M (2001) Making the most of your company's knowledge: a strategic framework. Long Range Planning 34 (4), 421–439.

Weiss HM (1990) Learning theory and industrial and organizational psychology. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology Vol. 1 (DUNNETTE MD and HOUGH LM, Eds), pp 171–221, Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA.

Yin RK (1994) Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Zack MH (1999) Developing a knowledge strategy. California Management Review 41 (3), 125–145.

Zack MH (2003) Rethinking the knowledge-based organization. Sloan Management Review 44 (4), 67–71.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Denford, J., Chan, Y. Knowledge strategy typologies: defining dimensions and relationships. Knowl Manage Res Pract 9, 102–119 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2011.7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2011.7