Abstract

Objectives

Psychosocial adaptation to climate change-related events remains understudied. We sought to assess how the psychosocial consequences of a major event were addressed via public health responses (e.g., programs, policies, and practices) that aimed to enhance, protect, and promote mental health.

Methods

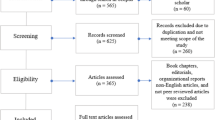

We report on a study of health and social service responses to the long-term mental health impacts of the 2013 Southern Alberta flood, in High River, Alberta. Qualitative research methods included (i) telephone interviews (n = 14) with key informant health and social services leaders, (ii) four focus group sessions with front-line health and social services workers (n = 14), and (iii) semi-structured interviews with a sample of community members (n = 18) who experienced the flood. We conducted a descriptive thematic analysis, with a focus on participants’ perceptions and experiences.

Results

Findings of this study suggest (1) the long-term psychosocial impacts of extreme weather and climate change require sustained recovery interventions rooted in local knowledge and interdisciplinary action; (2) there are unintended consequences related to psychosocial interventions that can incite complex emotions and impact psychosocial recovery; and (3) perceptions of mental health care, among people exposed to climate-related trauma, can guide climate change and mental health response and recovery interventions.

Conclusion

Based on this initial exploration, policy and practice opportunities for public health to enhance psychosocial adaptation to our changing climate are highlighted.

Résumé

Objectifs

L’adaptation psychosociale aux événements liés au changement climatique est encore sous-étudiée. Nous avons cherché à évaluer comment les conséquences psychosociales d’un événement majeur ont été abordées par des mesures de santé publique (p. ex. programmes, politiques, pratiques) visant à améliorer, à protéger et à promouvoir la santé mentale.

Méthode

Nous faisons le compte rendu d’une étude des mesures sociosanitaires appliquées pour remédier aux effets à long terme sur la santé mentale de l’inondation survenue en 2013 à High River, dans le Sud de l’Alberta. Nos méthodes de recherche qualitative ont compris : i) des entrevues téléphoniques (n = 14) avec des informateurs aux échelons supérieurs de la santé et des services sociaux; ii) quatre groupes thématiques avec des intervenants sociosanitaires de première ligne (n = 14); et iii) des entrevues semi-dirigées avec un échantillon de résidents (n = 18) touchés par l’inondation. Nous avons mené une analyse thématique descriptive axée sur les perceptions et l’expérience des participants.

Résultats

Selon les constatations de l’étude : 1) les impacts psychosociaux à long terme des conditions météorologiques exceptionnelles et du changement climatique nécessitent des interventions de rétablissement soutenues, ancrées dans les connaissances locales et dans l’action interdisciplinaire; 2) les interventions psychosociales peuvent avoir des effets pervers qui provoquent des émotions complexes et nuisent au rétablissement psychosocial; et 3) la perception des soins de santé mentale, chez les personnes exposées aux traumatismes d’origine climatique, peut guider la réaction au changement climatique et aux problèmes de santé mentale et les interventions de rétablissement.

Conclusion

Nous mettons en avant, à la lumière de cette première exploration, des possibilités d’améliorer l’adaptation psychosociale au changement climatique au moyen de politiques et de pratiques de santé publique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Psychosocial health encompasses states of mental well-being as well as mental ill-health and distress.

It is important to reflect here that marginalization of people occurs in an uneven world where discrimination based on race, gender, age, culture, and socio-economic status permeates the entire social fabric of society (Rudolph et al. 2018). Thus, at the core of the climate change and health problem area are issues of distributive justice, and more specifically climate injustice. Our aim was to explore how issues of distributive justice related to climate change and mental health were occurring in the local context of High River.

It is important to note here that there is no succinct definition of recovery, and that recovery can, in many cases, take a lifetime. For the purpose of this research, we understood recovery interventions to mean sustained responses that could support long-term needs.

A sense of community can be described as social cohesion, trust, and reciprocity that people experience in group settings.

Intersectoral (in this case) refers to multiple sectors (inside and outside of the health sector) that act together to support or enhance psychosocial adaptation in a changing climate.

References

Aldrich, D. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bajayo, R. (2012). Building community resilience to climate change through public health planning. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 23(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222930400014148.

Berry, H. L., Bowen, K., & Kjellstrom, T. (2010). Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. International Journal of Public Health, 55(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0112-0.

Bondy, M., & Cole, D. C. (forthcoming). Striving for balance and resilience – Ontario farmers’ perceptions of mental health. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Carleton, T. A. (2017). Crop-damaging temperatures increase suicide rates in India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201701354. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701354114.

Caxaj, S. (2016). A review of mental health approaches for rural communities: Complexities and opportunities in the Canadian context. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 35(1), 29–45.

Clayton, S., & Manning, C. (2018). Psychology and climate change - human perceptions, impacts, and responses. Psychology and climate change - human perceptions, impacts, and responses. San Diego: Elsevier.

Congues, J. M. (2014). Promoting collective well-being as a means of defying the odds: Drought in the Goulburn Valley, Australia. Rural Soc, 20(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371656.2014.11082067.

Cunsolo, A., & Ellis, N. R. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat Clim Chang. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2.

Cunsolo Willox, A., Harper, S. L., Ford, J. D., Edge, V. L., Landman, K., Houle, K., et al. (2013). Climate change and mental health: An exploratory case study from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Climatic Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0875-4.

Gil-Rivas, V., & Kilmer, R. P. (2016). Building community capacity and fostering disaster resilience. J Clin Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22281.

Haney, T. J., & McDonald-Harker, C. (2017). “The river is not the same anymore”: Environmental risk and uncertainty in the aftermath of the High River, Alberta flood. Social Currents, 4(6), 594–612.

Hardy, C., Kelly, K., & Voaklander, D. (2011). Does rural residence limit access to mental health services? Rural Remote Health, 11(1766), 1–8.

Hayes, K. (2019). Responding to a changing climate: An investigation of the psychosocial consequences of climate change and community-based mental health responses in High River. TSpace. University of Toronto. https://www.etdadmin.com/cgi-bin/student/mylist?siteId=623&submissionId=695377. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Hayes, K., Berry, P., & Ebi, K. L. (2019). Factors influencing the mental health consequences of climate change in Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 16(9), 1583 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6539500/.

Hull, M. J., Fennell, K. M., Vallury, K., Jones, M., & Dollman, J. (2017). A comparison of barriers to mental health support-seeking among farming and non-farming adults in rural South Australia. Aust J Rural Health, 25(6), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12352.

Hurlbert, M. (2018). Adaptive governance of disaster: Drougth and flood in rural areas. Geneva: Springer.

Judd, F., Jackson, H., Komiti, A., et al. (2006). Help-seeking by rural residents for mental health problems: The importance of agrarian values. Aust N Z J Psychiatry, 40, 769–776.

Katz, A. S., Hardy, B.-J., Firestone, M., Lofters, A., & Morton-Ninomiya, M. E. (2019). Vagueness, power and public health: Use of ‘vulnerable’ in public health literature. Crit Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1656800.

National Council of Non-Profits. (2019). Disaster recovery – what donors and nonprofits need to know. https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/tools-resources/disaster-recovery-what-donors-and- nonprofits-need-know. Accessed 2 June 2019.

Pacharui, R.K., Meyer, L.A. (Eds.) Climate change 2014: Synthesis report, contribution of working groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. Available online: http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/. Accessed 2 January 2018.

Parr, H. (2008). Chapter 3: Cultural landscapes: Rural communities and mental health. In Mental Health and Social Space. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Frankish, H., & Boyce, N. (2016). Sustainable development and global mental health—A Lancet Commission. Lancet, 387(10024), 1143–1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00208-7.

Rudolph, L., Harrison, C., Buckley, L., & North, S. (2018). Climate change, health, and equity: A guide for local health departments. Oakland and Washington, D.C..

Sahni, V., Scott, A. N., Beliveau, M., Varughese, M., Dover, D. C., & Talbot, J. (2016). Public health surveillance response following the southern Alberta floods, 2013. Can J Public Health, 107(2), 142–148.

Watts, M. J. (2015). The origins of political ecology and the rebirth of adaptation as a form of thought. In T. Perreault, G. Bridge, & J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of political ecology. New York: Routledge.

Weissbecker, I. (2011). Climate change and human well-being. Washington, DC: Springer Fachmedien.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the people of High River, interview participants, and focus group participants. Authors would also like to thank anonymous reviewers for their review. Acknowledgement of Material from Published Report: the authors would like to acknowledge that this submission includes material from Katie Hayes’ doctoral thesis—see Hayes, K. (2019). Responding to a Changing Climate: An Investigation of the Psychosocial Consequences of Climate Change and Community-based Mental Health Responses in High River. TSpace. University of Toronto. https://www.etdadmin.com/cgi-bin/student/mylist?siteId=623&submissionId=695377. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research was approved by the University of Toronto Ethics Board, the University of Alberta Ethics Board, and Alberta Health Services ethics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hayes, K., Poland, B., Cole, D.C. et al. Psychosocial adaptation to climate change in High River, Alberta: implications for policy and practice. Can J Public Health 111, 880–889 (2020). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00380-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00380-9