Abstract

Assessment of proarrhythmic toxicity of newly developed drugs attracts significant attention from drug developers and regulatory agencies. Although no guidelines exist for such assessment, the present experience allows several key suggestions to be made and an appropriate technology to be proposed.

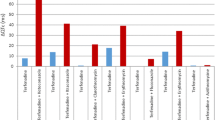

Several different in vitro and in vitro preclinical models exist that, in many instances, correctly predict the clinical outcome. However, the correspondence between different preclinical models is not absolute. None of the available models has been demonstrated to be more predictive and/or superior to others. Generally, compounds that do not generate any adverse preclinical signal are less likely to lead to cardiac toxicity in humans. Nevertheless, differences in likelihood offer no guarantee compared with entities with a preclinical signal. Thus, the preclinical investigations lead to probabilistic answers with the possibility of both false positive and false negative findings.

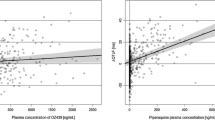

Clinical assessment of drug-induced QT interval prolongation is crucially dependent on the quality of electrocardiographic data and the appropriateness of electrocardiographic analyses. An integral part of this is a precise heart rate correction of QT interval, which has been shown to require the assessment of QT/RR relationship in each study individual. The numbers of electrocardiograms required for such an assessment are larger than usually obtained in pharmacokinetic studies. Thus, cardiac safety considerations need to be an integral part of early phase I/II studies.

Once proarrhythmic safety has been established in phase I/II studies, large phase III studies and postmarketing surveillance can be limited to less strict designs. The incidence of torsade de pointes tachycardia varies from 1 to 5% with clearly proarrhythmic drugs (e.g. quinidine) to 1 in hundreds of thousands with drugs that are still considered unsafe (e.g. terfenadine, cisapride). Thus, not recording any torsade de pointes tachycardia during large phase III studies offers no guarantee, and the clinical premarketing evaluation has to rely on the assessment of QT interval changes. However, since QT interval prolongation is only an indirect surrogate of predisposition to the induction of torsade de pointes tachycardia, any conclusion that a drug is safe should be reserved until postmarketing surveillance data are reviewed.

The area of drug-related cardiac proarrhythmic toxicity is fast evolving. The academic perspective includes identification of markers more focused compared with simple QT interval measurement, as well as identification of individuals with an increased risk of torsade de pointes. The regulatory perspective includes careful adaptation of new research findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schouten EG, Dekker JM, Meppelink P, et al. QT interval prolongation predicts cardiovascular mortality in an apparently healthy population. Circulation 1991; 84: 1516–23

de Bruyne MC, Hoes AW, Kors JA, et al. Prolonged QT interval predicts cardiac and all-cause mortality in the elderly. Eur Heart J 1999; 20: 278–84

Elming H, Holm E, Jun L, et al. The prognostic values of the QT interval and QT interval dispersion in all-cause and cardiac mortality and morbidity in a population of Danish citizens. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 1391–400

Kors JA, de Bruyne MC, Hoes AW, et al. T axis as an indicator of risk of cardiac events in elderly people. Lancet 1998; 352: 601–4

Selzer A, Wray HW. Quinidine syncope. Paroxysmal ventricular fibrillation occurring during treatment of chronic atrial arrhythmias. Circulation 1964; 30: 17–26

Roden DM, Woosley RL, Primm RK. Incidence and clinical features of the quinidine-associated long QT syndrome: implications for patient care. Am Heart J 1986; 111: 1088–93

Kay GN, Plumb VJ, Arciniegas JG, et al. Torsade de pointes: the long-short initiating sequence and other clinical features: observations in 32 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983; 2: 806–17

Bauman JL, Bauernfeind RA, Hoff JV, et al. Torsades de pointes due to quinidine: observations in 31 patients. Am Heart J 1984; 107: 425–30

Haverkamp W, Martinez RA, Hief C, et al. Efficacy and safety of d,l-sotalol in patients with ventricular tachycardia and in survivors of cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30: 487–95

Lehmann MH, Hardy S, Archibald D, et al. Sex difference in risk of torsade de pointes with d,l-sotalol. Circulation 1996; 94: 2535–41

Hohnloser SH. Proarrhythmia with class III antiarrhythmic drugs: types, risks, and management. Am J Cardiol 1997; 80: 82G–9G

Mishra A, Friedman HS, Sinha AK. The effects of erythromycin on the electrocardiogram. Chest 1999; 115: 983–6

Lipsky BA, Dorr MB, Magner DJ, et al. Safety profile of sparfloxacin, a new fluoroquinolone antibiotic. Clin Ther 1999; 21: 148–59

Woywodt A, Grommas U, Buth W, et al. QT prolongation due to roxithromycin. Postgrad Med J 2000; 76: 651–3

Haefeli WE, Schoenenberger RA, Weiss P, et al. Possible risk for cardiac arrhythmia related to intravenous erythromycin. Intensive Care Med 1992; 18: 469–73

Katapadi K, Kostandy G, Katapadi M, et al. A review of erythromycin-induced malignant tachyarrhythmia-torsade de pointes. A case report. Angiology 1997; 48: 821–6

Kamochi H, Nii T, Eguchi K, et al. Clarithromycin associated with torsade de pointes. Jpn Circ J 1999; 63: 421–2

Haverkamp W, Breithardt G, Camm AJ, et al. The potential for QT prolongation and proarrhythmia by non-antiarrhythmic drugs. Clinical and regulatory implications. Report on a policy conference of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2000; 21: 1216–31

Laughren T, Gordon M. FDA background on Zeldox™ (ziprasidone hydrochlorite capsules) Pfizer, Inc. Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee. July 19, 2000. Available from: URL: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/00/backgrd/3619b1b.pdf [Accessed 2000 Sep]

Buckley NA, Sanders P. Cardiovascular adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs. Drug Saf 2000; 23: 512–28

Nakamae H, Tsumura K, Hino M, et al. QT dispersion as a predictor of acute heart failure after high-dose cyclophosphamide. Lancet 2000; 335: 805–6

Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20: 1391–6

Feng J, Yue L, Wang Z, et al. Ionic mechanisms of regional action potential heterogeneity in the canine right atrium. Circ Res 1998; 83: 541–1

Hoppe UC, Beuckelmann DJ. Characterization of the hyperpolarization-activated inward current in isolated human atrial myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 1998; 38: 788–801

Veldkamp MW. Is the slowly activating component of the delayed rectifier current, IKs, absent from undiseased human ventricular myocardium? Cardiovasc Res 1998; 40: 433–5

El-Sherif N, Caref FB, Yin H, et al. The electrophysiological mechanism of ventricular arrhythmias in the long QT syndrome: tridimensional mapping of activation and recovery patterns. Circ Res 1996; 79: 474–92

Surawicz B. Electrophysiological substrate for Torsade de pointes: dispersion of refractoriness or early afterdepolarizations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989; 14: 172–84

Verduyn SC, Vos MA, Van der Zande J, et al. Role of interventricular dispersion of repolarization in acquired torsade-de-pointes arrhythmias: reversal by magnesium. Cardiovasc Res 1997; 34: 453–63

Antzelevitch C, Shimizu W, Yan GX, et al. The M cell: its contribution to the ECG and to normal and abnormal electrical function of the heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999; 10: 1124–52

Houltz B, Darpö B, Edvardsson N, et al. Electrocardiographic and clinical predictors of torsades de pointes induced by almokalant infusion in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation or flutter: a prospective study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1998; 21: 1044–57

Carmeliet E. Effects of cetirizine on the delayed K+ currents in cardiac cells: comparison with terfenadine. Br J Pharmacol 1998; 124: 663–8

Cavero I, Mestre M, Guillon JM, et al. Preclinical in vitro cardiac electrophysiology: a method of predicting arrhythmogenic potential of antihistamines in humans? Drug Saf 1999; 21Suppl. 1: S19–S31

Gilbert JD, Cahill SA, McCartney DG, et al. Predictors of torsades de pointes in rabbit ventricles perfused with sedating and nonsedating histamine H1-receptor antagonists. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2000; 78: 407–14

Delgado LF, Pferferman A, Sole D, et al. Evaluation of the potential cardiotoxicity of the antihistamines terfenadine, astemizole, loratadine, and cetirizine in atopic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998; 80: 333–7

DuBuske LM. Second-generation antihistamines: the risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Clin Ther 1999; 21: 281–95

Pagliara A, Testa B, Carrupt PA, et al. Molecular properties and pharmacokinetic behavior of cetirizine, a zwitterionic H1-receptor antagonist. J Med Chem 1998; 41: 853–63

Yue L, Feng JL, Wang Z, et al. Effects of ambasilide, quinidine, flecainide and verapamil on ultra-rapid delayed rectifier potassium currents in canine atrial myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 2000; 46: 151–61

Zhou Z, Vorperian VR, Gong Q, et al. Block of HERG potassium channels by the antihistamine astemizole and its metabolites desmethylastemizole and norastemizole. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999; 10: 836–43

Roy M, Dumaine R, Brown AM. HERG, a primary human ventricular target of the nonsedating antihistamine terfenadine. Circulation 1996; 94: 817–23

Rampe D, Roy ML, Dennis A, et al. A mechanism for the proarrhythmic effects of cisapride (Propulsid): high affinity blockade of the human cardiac potassium channel HERG. FEBS Lett 1997; 417: 28–32

Chouabe C, Drici MD, Romey G, et al. Effects of calcium channel blockers on cloned cardiac K+ channels IKr and IKs. Therapie 2000; 55: 195–202

Suessbrich H, Schonherr R, Heinemann SH, et al. The inhibitory effect of the antipsychotic drug haloperidol on HERG potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Br J Pharmacol 1997; 120: 968–74

De Cicco M, Marcor F, Robieux I, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of high-dose continuous intravenous verapamil infusion: clinical experience in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1999; 27: 332–9

Dascal N. The use of Xenopus oocytes for the study of ion channels. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 1987; 22: 341–56

Stühmer W, Parekh AB. Electrophysiological recordings from Xenopus oocytes. In: Sackmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-channel recordings. New York (NY): Plenum Press, 1995: 341–56

Fishman GI, McDonald TV. Gene transfer of membrane channel proteins. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J. editors. Cardiac electrophysiology. From cell to bedside. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Saunders Company, 2000: 58–66

Bril A, Gout B, Bonhomme M, et al. Combined potassium and calcium channel blocking activities as a basis for antiarrhythmic efficacy with low proarrhythmic risk: experimental profile of BRL-32872. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1996; 276: 637–46

Adamantidis MM, Caron JF, Bordet RC. Differential effects of antipsychotics and metabolites on action potentials recorded from rabbit Purkinje fibers: relationship with clinical case reports of QT prolongation and torsade de pointes [abstract]. Thérapie 2000; 55: 431

Kang J, Wang L, Chen X-L, et al. Interactions of a series of fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs with the human cardiac K+ channel HERG. Mol Pharmacol 2001; 59: 122–6

Patmore L, Fraser S, Mair D, et al. Effects of sparfloxacin, grepafloxacin, moxifloxacin, and ciprofloxacin on cardiac action potential duration. Eur J Pharmacol 2000; 406: 449–52

Drici MD, Wang WX, Liu XK, et al. Prolongation of QT interval in isolated feline hearts by antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18: 477–81

Sosunov EA, Gainullin RZ, Danilo PJ, et al. Electrophysiological effects of LU111995 on canine hearts: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999; 290: 146–52

Carlsson L, Amos GJ, Andersson B, et al. Electrophysiological characterization of the prokinetic agents cisapride and mosapride in vivo and in vitro: implications for proarrhythmic potential? J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 282: 220–7

Detweiler DK. Electrocardiography in toxicological studies. In: Sipes IG, McQueen CA, Gandolfi AJ, editors. Comprehensive toxicology. New York (NY): Pergamon Press, 1977: 95–114

Van de Water A, Verheyen J, Xhonneux R, et al. An improved method to correct the QT interval of the electrocardiogram for changes in heart rate. J Pharmacol Methods 1989; 22: 207–17

Chezalviel-Guilbert F, Davy JM, Poirier JM, et al. Mexiletine antagonizes effects of sotalol on QT interval duration and its proarrythmic effects in a canine model of torsade de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995; 26: 787–92

Weissenburger J, Davy JM, Chezalviel F, et al. Arrhythmogenic activities of antiarrhythmic drugs in conscious hypokalemic dogs with atrioventricular block: comparison between quinidine, lidocaine, flecainide, propranolol and sotalol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1991; 259: 871–3

Vos MA, Verduyn SC, Gorgels AP, et al. Reproducible induction of early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes arrhythmias by d-sotalol and pacing in dogs with chronic atrioventricular block. Circulation 1995; 91: 864–72

Vos MA, de Groot SHM, Verduyn SC, et al. Enhanced susceptibility for acquired torsade de pointes arrhythmias in the dog with chronic, complete AV block is related to cardiac hypertrophy and electrical remodeling. Circulation 1998; 98: 1125–35

Eckardt L, Haverkamp W, Borggrefe M, et al. Experimental models of torsade de pointes. Cardiovasc Res 1998; 39: 178–93

Sicouri S, Antzelevitch D, Heilmann C, et al. Effects of sodium channel block with mexiletine to reverse action potential prolongation in in vitro models of the long term QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1997; 8: 1280–90

Ko CM, Ducic I, Fan J, et al. Suppression of mammalian K+ channel family by ebastine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 281: 233–44

Malik M. Problems of heart rate correction in the assessment of drug induced QT interval prolongation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiology 2001. In press

Bazett JC. An analysis of time relations of electrocardiograms. Heart 1920; 7: 353–67

Fridericia LS. Die Systolendauer im Elekrokardiogramm bei normalen Menschen und bei Herzkranken. Acta Med Scand 1920; 53: 469–86

Hodges M. Rate correction of the QT interval. Cardiac Electrophysiol Rev 1997; 1: 360–3

Waller AD. A demonstration on man of electromotive changes accompanying the heart’s beat. J Physiol 1887; 8: 229–35

Mayeda I. On time relation between systolic duration of heart and pulse rate. Acta Sch Med Univ Kioto 1934; 17: 53–5

Adams W. The normal duration of the electrocardiographic ventricular complex. J Clin Invest 1936; 15: 335–42

Ashman R. The normal duration of the Q-T interval. Am Heart J 1942; 522–34

Simonson E, Cady LD, Woodbury M. The normal Q-T interval. Am Heart J 1962; 63: 747–53

Sarma JSM, Sarma RJ, Bilitch M, et al. An exponential formula for heart rate dependence of QT interval during exercise and pacing in humans: reevaluation of Bazett’s formula. Am J Cardiol 1984; 54: 103–8

Hodges M, Salerno D, Erlien D. Bazett’s QT correction reviewed: evidence that a linear QT correction for heart rate is better. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983; 1: 694

Kawataki M, Kashima T, Toda H, et al. Relation between QT interval and heart rate: applications and limitations of Bazett’s Formula. J Electrocardiol 1984; 17: 371–5

Sagie A, Larson MG, Goldberg RJ, et al. An improved method for adjusting the QT interval for heart rate (the Framingham study). Am J Cardiol 1992; 70: 797–801

Rautaharju PM, Warren JW, Calhoun HP. Estimation of QT prolongation: a persistent, avoidable error in computer electrocardiography. J Electrocardiol; 23Suppl.: 111–7

Karjalainen J, Viitasalo M, Manttari M, et al. Relation between QT intervals and heart rates from 40 to 120 beats/min in rest electrocardiograms of men and a simple method to adjust QT interval values. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994; 23: 1547–53

Kautzner J, Hnatkova K, Camm AJ, et al. Dependence of resting QTc interval on clinical characteristics of survivors of acute myocardial infarction: comparison of rate correction formulae [abstract]. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1997; 19: 334

Lazzara R. Antiarrhythmic drugs and torsade de pointes. Eur Heart J 1993; 14Suppl. H: 88–92

Malik M. If Dr Bazett had had a computer. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1996; 19: 1635–39

Hnatkova K, Malik M. ‘Optimum’ formulae for heart rate correction of the QT interval. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1999; 22: 1683–7

Batchvarov V, Färbom P, Dilaveris P, et al. No single formula for heart rate correction of the QT interval is suitable for all individuals [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001: 37Suppl. A; 91A

Batchvarov V, Ghuran A, Dilaveris P, et al. The 24-hour QT/RR relation in healthy subjects is reproducible in the short- and long term [abstract]. Ann Noninvas Electrocardiol 2000; 5: S57

Batchvarov V, Ghuran A, Hnatkova K, et al. Short- and long-term reproducibility of the QT/RR relationship in healthy subjects [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 37Suppl. A: 101A

Choy AM, Lang CC, Roden DM, et al. Abnormalities of the QT interval in primary disorders of autonomic failure. Am Heart J 1998; 136: 664–71

Antimisiaris M, Sarma JS, Schoenbaum MP, et al. Effects of amiodarone on the circadian rhythm and power spectral changes of heart rate and QT interval: significance for the control of sudden cardiac death. Am Heart J 1994; 128: 884–91

Fauchier L, Babuty D, Poret P, et al. Effect of verapamil on QT interval dynamicity. Am J Cardiol 1999; 83: 807–808

Sharma PP, Sarma JS, Singh BN. Effects of sotalol on the circadian of heart rate and QT intervals with a noninvasive index of reverse-use dependency. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 1999; 4: 15–21

Gang Y, Guo X, Crook R, et al. Computerised measurement of QT dispersion in healthy subjects. Heart 1998; 80: 459–66

Morganroth J, Brown AM, Critz S, et al. Variability of the QTc interval: impact on defining drug effect and low-frequency cardiac event. Am J Cardiol 1993; 72: 26B–31B

Molnar J, Zhang F, Weiss J, et al. Diurnal pattern of QTc interval: how long is prolonged? Possible relation to circadian triggers of cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996; 27: 76–83

Neyroud N, Maison-Blanche P, Denjoy I, et al. Diagnostic performance of QT interval variables from 24-h electrocardiography in the long QT syndrome. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 158–65

Gang Y, Guo X-H, Reardon M, et al. Circadian variation of the QT interval in patients with sudden cardiac death after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81: 950–6

Batchvarov V, Farböm P, Dilaveris P, et al. Bazett formula is not suitable for assessment of the circadian variation of the heart-rate corrected QT interval [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001. In press

Lau CP, Freeman AR, Fleming SJ, et al. Hysteresis of the ventricular paced QT interval in response to abrupt changes in pacing rate. Cardiovasc Res 1988; 22: 67–72

Koide T, Ozeki K, Kaihara S, et al. Etiology of QT prolongation and T wave changes in chronic alcoholism. Jpn Heart J 1981; 22: 151–66

Yokoyama A, Ishii H, Takagi T, et al. Prolonged QT interval in alcoholic autonomic nervous dysfunction. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1992; 16: 1090–2

Perera R, Kraebber A, Schwartz MJ. Prolonged QT interval and cocaine use. J Electrocardiol 1997; 30: 337–9

Gamouras GA, Monir G, Plunkitt K, et al. Cocaine abuse: repolarization abnormalities and ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Med Sci 2000; 320: 9–12

Watanabe Y. Purkinje repolarization as a possible cause of the U wave in the electrocardiogram. Circulation 1975; 51: 1030–7

Lepeschkin E. Physiologic basis of the U wave. In: Schlant RC, Hurst JW, editors. Advances in electrocardiography. New York (NY): Grune and Stratton, 1972: 431–7

Antzelevich C, Nesterenko VV, Yan GX. The role of M cells in acquired long QT syndrome, U waves and torsade de pointes. J Electrocardiol 1996; 28Suppl. 131–8

Yan G-Y, Antzelevich C. Cellular basis for the normal T wave and the electrocardiographic manifestations of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation 1998; 98: 1928–36

Kautzner J, Yi G, Kishore R, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of QT interval measurement and QT dispersion in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Noninvas Electrocardiol 1996; 1: 363–74

Benardeau A, Weissenburger J, Hondeghem L, et al. Effects of the T-type Ca(2+) channel blocker mibefradil on repolarization of guinea pig, rabbit, dog, monkey, and human cardiac tissue. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000; 292: 561–75

Lepeschkin E, Surawicz B. The measurement of the Q-T interval of the electrocardiogram. Circulation 1952; 6: 378–88

Malik M. Bradford A. Human precision of operating a digitizing board: implications for electrocardiogram measurement. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1998; 21: 1656–62

Dilaveris P, Batchvarov V, Gialafos J, et al. Comparison of different methods for manual P wave duration measurement in 12-lead electrocardiograms. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1999; 22: 1532–8

Zabel M, Klingenheben T, Franz MR, et al. Assessment of QT dispersion for prediction of mortality or arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction: results of a prospective, long-term follow-up study. Circulation 1998; 97: 2543–50

Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP). Points to consider: the assessment of the potential for QT interval prolongation by non-cardiovascular medicinal products. London: The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products; 1997 Dec

Hnatkova K, Malik D, Kishore R, et al. Computer system for measurement of QT and QU intervals and for evaluation of QT dispersion in standard 12 lead electrocardiograms. Eur J Card Pac Electrophysiol 1996; 6Suppl. 5: 113

Batchvarov V, Yi G, Guo X, et al. QT interval and QT dispersion measured with the threshold method depend on threshold level. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1998; 21: 2372–5

Day CP, McComb LM, Campbell RWF. QT dispersion: an indication of arrhythmia risk in patients with long QT intervals. Br Heart J 1990; 63: 342–244

Surawicz B. Long QT: good, bad, indifferent and fascinating. ACC Curr J Rev 1999; 19–21

Kautzner J, Yi G, Camm AJ, et al. Short- and long-term reproducibility of QT, QTc, and QT dispersion measurement in healthy subjects. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1994; 17: 928–37

Macfarlane PW, McLaughlin SC, Rodger C. Influence of lead selection and population on automated measurement of QT dispersion. Circulation 1998; 98: 2160–7

Surawicz B. Will QT dispersion play a role in clinical decision-making? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1996; 7: 777–84

Rautaharju PM. QT and dispersion of ventricular repolarization: the greatest fallacy in electrocardiography in the 1990s. Circulation 1999; 18: 2477–8

Malik M, Batchvarov VN. Measurement, interpretation and clinical potential of QT dispersion. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 1749–66

Honig PK, Wortham DC, Zamani K, et al. Terfenadine-ketoconazole interaction: pharmacokinetic and electrocardiographic consequences. JAMA 1993; 269: 1513–8

Benton RE, Honig PK, Zamani K, et al. Grapefruit juice alters terfenadine pharmacokinetics, resulting in prolongation of repolarization on the electrocardiogram. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996; 59: 383–8

Honig PK, Woosley RL, Zamani K, et al. Changes in the pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic pharmacokinetics of terfenadine with concomitant administration of erythromycin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1992; 52: 231–8

Honig PK, Wortham DC, Lazarev A, et al. Grapefruit juice alters the systemic bioavailability and cardiac repolarisation of terfenadine in poor metabolizers of terfenadine. J Clin Pharmacol 1996; 36: 345–51

Stern RH, Smithers JA, Olson SC. Atorvastatin does not produce a clinically significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of terfenadine. J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 38: 753–7

Honig PK, Wortham DC, Zamani K, et al. Effect of concomitant administration of cimetidine and ranitidine on the pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic effects of terfenadine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 45: 41–6

Honig PK, Wortham DC, Zamani K, et al. Comparison of the effect of the macrolide antibiotics erythromycin, clarithromycin and azithromycin on terfenadine steady-state pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic parameters. Drug Invest 1994; 7: 148–56

Goldberg M, Ring B, DeSante K, et al. Effect on dirithromycin on human CYP3A in vivo and on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of terfenadine in vivo. J Clin Pharmacol 1996; 36: 1154–60

Honig PK, Wortham DC, Hull R, et al. Itraconazole affects single-dose terfenadine pharmacokinetics and cardiac repolarization pharmacodynamics. J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 33: 1201–6

Martin DE, Zussman BD, Everitt DE, et al. Paroxetine does not affect the cardiac safety and pharmacokinetics of terfenadine in healthy adult men. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17: 451–9

Harris S, Hilligoss DM, Colangelo PM, et al. Azithromycin and terfenadine: lack of drug interaction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1995; 58: 310–5

Vargo D, Suttle A, Wildinson L, et al. Effects of zafirlukast on QTc and area under the curve on terfenadine in healthy men. J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 37: 858–78

Clifford C, Adams D, Murray S, et al. The cardiac effects of terfenadine after inhibition of its metabolism by grapefruit juice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 52: 311–5

Awni W, Cavanaugh J, Leese P, et al. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interaction between zileuton and terfenadine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 52: 49–54

van Haarst AD, van’t Klooster GAE, van Gerven JMA, et al. The influence of cisapride and clarithromycin on QT intervals in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1998; 64: 542–6

Kivistö KT, Lilja JJ, Backman JT, et al. Repeated consumption of grapefruit juice considerably increases plasma concentrations of cisapride. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999; 66: 448–53

Pollak PT. Oral amiodarone. Pharmacotherapy 1998; 18: 121S–6S

Ebert SN, Liu XK, Woosley RL. Female gender as a risk factor for drug-induced cardiac arrhythmias: evaluation of clinical and experimental evidence. J Womens Health 1998; 7: 547–7

Benton RE, Sale M, Flockhart DA, et al. Greater quinidine-induced QTc interval prolongation in women. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000; 67: 413–8

Walker AM, Szeneke P, Weartherby LB, et al. The risk of serious cardiac arrhythmias among cisapride users in the United Kingdom and Canada. Am J Med 1999; 107: 356–62

Food and Drug Administration. Cisapride. FDC Report 2000, Jan 30

Miller JL. FDA, Janssen bolster cardiac risk warnings for cisapride. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2000 57: 414

Ludomirsky A, Klein HO, Sarelli P, et al. Q-T prolongation and polymorphous (‘torsade de pointes’) ventricular arrhythmias associated with organophosphorus insecticide poisoning. Am J Cardiol 1982; 49: 1654–8

Raikhin-Eisenkraft B, Nutenko I, Kniznik D, et al. Death from fluoro-silicate in floor polish [in Hebrew]. Harefuah 1994; 126: 258–9

Pratt C, Brow AM, Rampe D, et al. Cardiovascular safety of fexofenadine HCl. Clin Exp Allergy 1999; 29Suppl. 3: S212–S6

Pinto YM, van Gelder IC, Heeringa M, et al. QT lengthening and life-threatening arrhythmias associated with fexofenadine. Lancet 1999; 353: 980

Tie H, Walker BD, Singleton CB, et al. Inhibition of HERG potassium channels by the antimalarial agent halofantrine. Br J Pharmacol 2000; 130: 1967–75

Monlun E, Pillet O, Cochard JF, et al. Prolonged QT interval with halofantrine. Lancet 1993; 341: 1541–2

Toivonen L, Viitasalo M, Siikamaki H, et al. Provocation of ventricular tachycardia by antimalarial drug halofantrine in congenital long QT syndrome. Clin Cardiol 1994; 17: 403

Akhtar T, Imran M. Sudden deaths while on halofantrine treatments - a report of two cases from Peshawar. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc 1994; 44: 120–1

Bakshi R, Hermeling-Fritz I, Gathmann I, et al. An integrated assessment of the clinical safety of artemether-lumefantrine: a new oral fixed-dose combination antimalarial drug. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2000; 94: 419–24

Wesch DL, Dchuster BG, Wang WX, et al. Mechanism of cardiotoxicity of halofantrine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000; 67: 521–9

Cavuto NJ, Woosley RL, Sale M, et al. Pharmacies and prevention of potentially fatal drug interactions. JAMA 1996; 275: 1086–7

Thompson D, Oster G. Use of terfenadine and contraindicated drugs. JAMA 1996; 275: 1339–41

Anon. Janssen Propulsid prescribing for inpatients questioned in three studies. FDC Rep 1998; 60: 26

Puddu PE, Bernard PM, Chaitman BR, et al. QT interval measurement by a computer assisted program: a potentially useful clinical parameter. J Electrocardiol 1982; 15: 15–21

Fayn J, Rubel P, Mohsen N. An improved method for the precise measurement of serial ECG changes in QRS duration and QT interval. Performance assessment on the CSE noise-testing database and a healthy 720 case-set population. J Electrocardiol 1992; 24Suppl.: 123–7

Bhullar HK, Fothergill JC, Goddard WP, et al. Automated-measurement of QT interval dispersion from hard-copy ECGs. J Electrocardiol 1993; 26: 321–31

Laguna P, Jane R, Caminal P. Automatic detection of wave boundaries in multilead ECG signals: validation with the CSE database. Comput Biomed Res 1994; 27: 45–60

Rubel P, Hamidi S, Behlouli H, et al. Are serial Holter QT, late potential, and wavelet measurement clinically useful? J Electrocardiol 1996; 29Suppl.: 52–61

Reddy BR, Xue Q, Zywietz C. Analysis of interval measurements on CSE multilead reference ECGs. J Electrocardiol 1996; 29Suppl.: 62–6

Hoon TJ. Performance of an electrocardiographic analysis system: implications for pharmacodynamic studies. Pharmacotherapy 1996; 16: 230–6

Glancy JM, Weston PJ, Bhullar HK, et al. Reproducibility and automatic measurement of QT dispersion. Eur Heart J 1996; 17: 1035–9

Xue Q, Reddy S. Algorithms for computerized QT analysis. J Electrocardiol 1998; 30: 181–6

Tikkanen PE, Sellin LC, Kinnunen HO, et al. Using simulated noise to define optimal QT intervals for computer analysis of ambulatory ECG. Med Eng Phys 1999; 21: 15–25

Savelieva I, Yi G, Guo X, et al. Agreement and reproducibility of automatic versus manual measurement of QT interval and QT dispersion. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81: 471–7

Vila JA, Yi G, Rodríguez Presedo AM, et al. A new approach for TU complex characterization. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2000; 47: 764–72

Acar B, Yi G, Hnatkova K, et al. Spatial, temporal and wavefront direction characteristics of 12-lead T wave morphology. Med Biol Eng Comput 1999; 37: 574–84

Zabel M, Acar B, Klingenheben T, et al. Analysis of twelve-lead T wave morphology for risk stratification after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2000; 102: 1252–7

Hnatkova K, Ryan SJ, Bathen J, et al. T-wave morphology differentiates between patients with and without arrhythmic complications of ischaemic heart disease. J Electrocardiol 2001. In press

Zhang L, Timothy KW, Vincent M, et al. Spectrum of ST-T wave patterns and repolarisation parameters in congenital long-QT syndrome: ECG findings identify genotypes. Circulation 2000; 102: 2849–55

Sesti F, Abbott GW, Wei J, et al. A common polymorphism associated with antibiotic-induced cardiac arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97: 10613–8

Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Brown AM, et al. Evidence for a cardiac ion channel mutation underlying drug-induced QT prolongation and life-threatening arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2000; 11: 691–6

Clancy CE, Rudy Y. Linking a genetic defect to its cellular phenotype in a cardiac arrhythmia. Nature 1999; 400: 566–9

Roden DM, Kupershmidt S. From genes to channels: normal mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res 1999; 42: 318–26

Darbar D, Smith M, Morike K, et al. Epinephrine-induced changes in serum potassium and cardiac repolarization and effects of pretreatment with propranolol and diltiazem. Am J Cardiol 1996; 77: 1351–5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malik, M., Camm, A.J. Evaluation of Drug-Induced QT Interval Prolongation. Drug-Safety 24, 323–351 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200124050-00001

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200124050-00001