Summary

Abstract

Losartan is an orally active, nonpeptide, selective angiotensin subtype 1 (AT1) receptor antagonist. It provides a more specific and complete blockade of the actions of angiotensin II than renin or ACE inhibitors.

Short term (up to 12 weeks’ duration) clinical trials have shown losartan to be as effective at lowering blood pressure (BP) [causes a decrease in BP ≤26/20mm Hg] in elderly patients with hypertension as recommended dosages of captopril, atenolol, enalapril, felodipine and nifedipine. In patients with isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) the efficacy of losartan was similar to that of atenolol. The addition of hydrochlorothiazide to losartan therapy provides greater antihypertensive efficacy, equivalent to that seen with captopril plus hydrochlorothiazide. Preliminary evidence also indicates that losartan therapy contributes to the regression of left ventricular hypertrophy associated with chronic hypertension.

Exercise capacity is increased by losartan in patients with either asymptomatic or symptomatic heart failure. Results from the Losartan Heart Failure Survival or ELITE II (Evaluation of Losartan in the Elderly II) study indicate that there was no statistically significant difference between losartan and captopril in reducing overall deaths or in reducing sudden cardiac death and/or resuscitated cardiac arrest in patients with heart failure.

Other than ELITE II, little conclusive long term mortality and morbidity data exist for losartan. Additional long term trials to evaluate the survival benefits of losartan in elderly patients with hypertension, renal disease or after an acute myocardial infarction are currently in progress.

In elderly patients with hypertension, the incidence of treatment-related adverse events associated with once daily losartan (alone or in combination with hydrochlorothiazide) [19 to 27%] was similar to felodipine (23%) and nifedipine (21%), however, losartan tended to be better tolerated than captopril (11 vs 16%). Losartan was also better tolerated than atenolol in patients with ISH (10.4 vs 23%). In patients with heart failure the renal tolerability of losartan was similar to that of captopril, but losartan was associated with a lower withdrawal rate because of adverse events. No dosage adjustment is required in elderly or in patients with mild to moderate renal dysfunction, and the risk of first-dose hypotension is low.

Conclusions: comparative data have shown losartan to be as effective as other antihypertensive agents in the treatment of elderly patients with hypertension. Treatment with losartan is therefore an option for first-line therapy in all patients with hypertension, particularly those who are not well managed with or who are intolerant of their current therapy. Morbidity and mortality data from the Losartan Heart Failure Survival (ELITE II) study show that losartan has potential in the treatment of heart failure.

Pharmacodynamic Properties

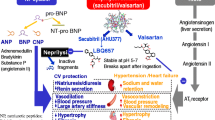

Losartan is an orally active, nonpeptide, selective angiotensin subtype 1 (AT1) receptor antagonist. It provides a more specific and complete blockade of the actions of angiotensin II than renin or ACE inhibitors.

The active parent losartan is converted into an active metabolite E3174, which is 15 to 20 times more potent at blocking the angiotensin receptor subtype 1 (AT1). Losartan preserves renal function and reduces proteinuria. Preliminary evidence indicates that losartan therapy contributes to the regression of left ventricular hypertrophy associated with chronic hypertension. It has beneficial effects on left ventricular mass index, systemic vascular resistance, BP, pulomonary capillary wedge pressure, heart rate and cardiac index. In patients with heart failure, losartan had a more gradual effect on BP than captopril. In contrast to captopril, losartan had no negative effects on QT dispersion in patients with heart failure. Unlike ACE inhibitors, losartan appears to have no effect on haematology (haemoglobin and plasma erythropoietin levels) and haemorheology. It improves baroreceptor function in elderly patients with hypertension.

Pharmacokinetic Properties

After oral administration losartan is rapidly absorbed, reaching peak plasma concentrations within an hour, while plasma concentrations of the active metabolite E3174 peak approximately 4 hours after administration. The drug undergoes significant first pass metabolism with about 14% of the dose converted into E3174. The pharmacokinetic properties of losartan are similar in volunteers and patients with heart failure and there appears to be no clinically significant accumulation of the drug in these patients.

Renal impairment did not alter the pharmacokinetic properties of losartan. However, in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis, plasma concentrations of losartan and E3714 were increased and the dosage should be adjusted for such patients.

Losartan did not interact with single-dose warfarin, digoxin or hydrochlorothiazide. Drugs that affect the cytochrome P450 system have the potential to affect the pharmcokinetics of losartan.

Therapeutic Efficacy

Studies (generally of 12 weeks’ duration) in elderly patients indicate that the antihypertensive efficacy of losartan 50 or 100mg once daily (causes a decrease in BP of ≤26/20mm Hg) is similar to that of other antihypertensive agents, including once daily enalapril 10 or 20mg, captopril 50 or 100mg, nifedipine gastrointestinal system (GITS) 30 to 90mg and felodopine extended release 5 or 10mg. In addition, once daily losartan 50mg and atenolol 50mg had similar antihypertensive efficacy in patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The addition of hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 or 25mg to losartan produces additional BP decreases. A fixed combination of losartan 50mg/hydrochlorothiazide 12.5mg was as effective at reducing BP as captopril 50mg/hydrochlorothiazide 25mg.

Fewer patients with mild to moderate hypertension required switching to alternative therapy with a systematic losartan-based regimen than with usual care in a community-based study. The losartan regimen included losartan 50mg, losartan 50mg plus hydrchlorothiazide 12.5 or 25mg, followed by any other additional therapy (except angiotensin II antagonists) as required for adequate blood pressure control.

Losartan had a more favourable effect on quality of life than enalapril in elderly patients with hypertension. However, the drug had a similar effect on quality of life to nifedipine GITS, although the total number of adverse events reported with nifedipine GITS was greater than in losartan recipients.

Despite the promising results of the Losartan Heart Failure (ELITE I) study which showed a significant 32% reduction in the risk of death or admission to hospital for heart failure compared with captopril-treated patients, the Losartan Heart Failure Survival (ELITE II) study found no significant difference in all cause mortality between the 2 treatments. In addition, no differences were observed in sudden death, heart failure mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke or noncardiovascular death between the 2 groups. However, confirming the results of the Losartan Heart Failure (ELITE I) study, losartan was better tolerated than captopril. In this initial study, losartan and captopril produced similar improvements in quality of life after 48 weeks, although more captopril-treated patients withdrew from the study because of adverse reactions.

In patients with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, losartan increased exercise tolerance, and reduced and delayed peak systolic BP during exercise. Losartan also improved exercise tolerance (including exercise time, oxygen consumption and ejection fraction) in patients with symptomatic heart failure to a similar extent to enalapril. Short term studies have indicated that the addition of losartan to an ACE inhibitor may provide additional benefits in patients with severe heart failure not sufficiently controlled by their current regimen.

Tolerability

Losartan 50 or 100mg, alone or in combination with low dose hydrochlorothiazide was well tolerated in elderly patients with hypertension. Headache, asthenia, oedema and upper respiratory tract infections were the most commonly reported adverse events occurring in approximately 5 to 10% of patients. The incidence of treatment-related adverse events in patients treated with losartan (19 to 27%) was similar to that in recipients of felodipine 5 or 10mg (23%) and nifedipine (21%), however, losartan tended to be better tolerated than captopril (11 vs 16%). Importantly, the incidence of cough was significantly (p < 0.05) lower with losartan/hydrochlorothiazide than with captopril/hydrochlorothiazide. Losartan was better tolerated than atenolol in patients with ISH (10.4 vs 23%). There were also significantly less withdrawals because of adverse events in losartan-treated patients than in those receiving atenolol (1.5 vs 7.2%).

In the Losartan Heart Failure (ELITE I) study the renal tolerability of losartan was similar to that of captopril in patients with heart failure after 48 weeks’ treatment (incidence of persistent increases in serum creatinine ≥26.5 μmol/L 10.5% each). However, there were more withdrawals from treatment among captopril recipients than those on losartan (20.8 vs 12.2%). Losartan was also better tolerated than captopril in the Losartan Heart Failure Survival (ELITE II) study and a higher number of patients treated with captopril withdrew because of adverse events than those on losartan.

Dosage and Administration

The recommended starting and maintenance dosage of losartan is 50mg once daily in patients with essential hypertension. If patients are not responding to losartan monotherapy a stepwise titration may be used to once daily losartan 50mg in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide 12.5mg and, if required, once daily losartan 100mg plus hydrochlorothiazide 25mg. A starting dosage of 25mg daily should be used in patients with severe renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance <1.2 L/h (20 ml/min)] or on dialysis and in those who have intravascular volume depletion or hepatic impairment. However, no dosage adjustment is required in elderly or in patients with mild to moderate renal dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jackson EK, Garrison JC. Renin and angiotensin. In: Hartman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, et al., editors. Goodman & Gillman’s The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 9th ed. Auckland: McGraw-Hill, 1996: 733–54

Burrell LM, Johnston CI. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists: potential in elderly patients with cardiovascular disease. Drugs Aging 1997 Jun; 10: 421–34

Gibbons GH. The pathophysiology of hypertension: the importance of angiotensin II in cardiovascular remodeling. Am J Hypertens 1998; 11: 177S–81S

Guidelines Subcommittee of the WHO-ISH. 1999 World Health Organization — International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. J Hypertens 1999 Feb; 17: 151–83

Shammas E, Dickstein K. Drug selection for optimal treatment of hypertension in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1997 Jul; 11: 19–26

Cushman WC. The clinical significance of systolic hypertension. Am JHypertens 1998; 11: 182S–5S

Cohn JN. The management of chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 1996; 335(7): 490–8

Kleber FX, Wensel R. Current guidelines for the treatment of congestive heart failure. Drugs 1996 Jan; 51: 89–98

Ramsay LE, Wallis EJ, Yeo W, et al. The rationale for differing national recommendations for the treatment of hypertension. Am J Hypertens 1998 Jun; 11 (Pt 2): 79–88

Andersson F, Cline C, Ryden-Bergsten T, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and heart failure: the consequences of underprescribing. Pharmacoeconomics 1999; 15(6): 535–50

Dzielak DJ. Comparative pharmacology of the angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Expert Opin Invest Drug 1998 May; 7: 741–51

Goa KL, Wagstaff AJ. Losartan potassium: a review of its pharmacology, clinical efficacy and tolerability in the management of hypertension. Drugs 1996 May; 51: 820–45

Chiu AT, McCall DE, Ardecky RJ, et al. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes and their selective nonpeptide ligands. Receptor 1990-91; Winter, 1:33–40

Chiu AT, McCall DE, Aldrich PE, et al. [3H]DUP 753, a highly potent and specific radioligand for the angiotensin II-1 receptor subtype. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1990 Nov; 172: 1195–202

Wong PC, Price WA, Chiu AT, et al. Nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists. XL Pharmacology of EXP3174: an active metabolite of DuP753, an orally active antihypertensive agent. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990 Oct; 255: 211–7

Wong PC, Price WA, Chiu AT, et al. Nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists. IX. Antihypertensive activity in rats of DuP753, an orally active antihypertensive agent. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990 Feb; 252: 726–32

Christen Y, Waeber B, Nussberger J, et al. Dose-response relationships following administration of DuP 753 to normal humans. Am J Hypertens 1991 Apr; 4 Suppl.: 350S–3S

Munafo A, Christen Y, Nussberger J, et al. Drug concentration response relationships in normal volunteers after oral administration of losartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1992 May; 51: 513–21

Burnier M, Rutschmann B, Nussberger J, et al. Salt-dependent renal effects of an angiotensin II antagonist in healthy subjects. Hypertension 1993 Sep; 22: 339–47

Azizi M, Chatellier G, Guyene T-T, et al. Additive effects of combined angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II antagonism on blood pressure and renin release in sodium-depleted normotensives. Circulation 1995; 92: 825–34

Goldberg MR, Tanaka W, Barchowsky A, et al. Effects of losartan on blood pressure, plasma renin activity, and angiotensin II in volunteers. Hypertension 1993 May; 21: 704–13

Doig JK, MacFayden RJ, Sweet CS, et al. Dose-ranging study of the angiotensin type I receptor antagonist losartan (DuP753/MK954), in salt-deplete normal man. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1993 May; 21: 732–8

Cockcroft JR, Sciberras DG, Goldberg MR, et al. Comparison of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with angiotensin II receptor antagonism in the human forearm. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1993 Oct; 22: 579–84

Erley CM, Bader B, Scheu M, et al. Renal hemodynamics in essential hypertensives treated with losartan. Clin Nephrol 1995 Jan; 43Suppl. 1: S8–11

Chan JC, Critchley AJH, Tomlinson B, et al. Antihypertensive and anti-albuminuric effects of losartan potassium and felodipine in Chinese elderly hypertensive patients with or without non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Nephrol 1997; 17: 72–80

Tsunoda K, Abe K, Hagino T, et al. Hypotensive effect of losartan, a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist, in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 1993 Jan; 6: 28–32

Smith MC, Barrows S, Meibohm A, et al. The effects of angiotensin II receptor blockade with losartan on systemic blood pressure and renal and extrarenal prostaglandin synthesis in women with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 1995 Dec; 8(12 Pt 1): 1177–83

Laviades C, Diez J. Is the hypouricemic effect of losartan in hypertensive patients related to a lesser production of uric acid? J Hum Hypertens 1999 May; 13Suppl. 3: S2

Alderman MH, Cohen H, Madhavan S, et al. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular events in successfully treated hypertensive patients. Hypertension 1999; 34: 144–50

Moan A, Håieggen A, Seljeflot I, etal. The effect of angiotensin II receptor antagonism with losartan on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. J Hypertens 1996 Sep; 14: 1093–7

Shand BI, Gilchrist NL, Nicholls MG, et al. Effect of losartan on haematology and haemorheology in elderly patients with essential hypertension: a pilot study. J Hum Hypertens 1995 Apr; 9: 233–5

Yee KM, Struthers AD. Endogenous angiotensin II and baro-receptor dysfunction: a comparative study of losartan and enalapril in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 46: 583–8

Tedesco MA, Ratti G, Aquino D, et al. Effects of losartan on hypertension and left ventricular mass: a long-term study. J Hum Hypertens 1998 Aug; 12: 505–10

Lonati L, Cuspidi C, Sampieri L, et al. The effect of losartan on left ventricular mass in hypertensive patients: double blind comparison study with verapamil [abstract]. Am J Hypertens 1998 Apr; 11 (Pt 2): 119

Crozier I, Ikram H, Awan N, et al. Losartan in heart failure: hemodynamic effects and tolerability. Circulation 1995; 91: 691–7

Konstam MA. Comparative effects of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blocking agents on left ventricular volumes in elderly patients with heart failure. Am J Manage Care 1998 Jul; 4 Suppl.: S377–9

Brooksby P, Cowley AJ, Segal R, et al. Effects of losartan and captopril on QT-dispersion in elderly patients with heart failure in the ELITE study: an initial assessment [abstract]. Eur Heart J 1998 Aug; 19 Abstr. Suppl.: 133

Nielsen S, Dollerup J, Nielsen B, et al. Losartan reduces albuminuria in patients with essential hypertension: an enalapril controlled 3 months study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997; 12Suppl. 2: 19–23

Gottlieb SS, Dickstein K, Fleck E, et al. Hemodynamic and neurohormonal effects of the angiotensin II antagonist losartan in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 1993; 88 (Pt 1): 1602–9

Tedesco MA, Ratti G, Mennella AC, et al. Long-term effects of losartan on hypertension and left ventricular mass in elderly patients. Am J Hypertens 1999; 12 (4 Pt 2): 117A

Squire IB, Robb S, Dargie HJ, et al. Comparative haemodynamic and renin angiotensin system responses to the first dose of losartan or captopril in elderly patients with CHF [abstract]. Eur Heart J 1998 Aug; 19 Abstr. Suppl.: 402

Griffing GT, Melby JC. Enalapril (MK-421) and the white cell count and haematocrit [letter]. Lancet 1982; I: 1361

Ernst E, Bergmann H. Influence of cilazapril on blood rheology in healthy subjects. Am J Med 1989; 87 Suppl. 6B: 70S–1S

Zannad F, Bray-Desboscs L, El Ghawi R, et al. Effects of isinopril and hydrochlorothiazide on platelet function and blood rheology in essential hypertension: a randomly allocated double-blind study. Hypertension 1993; 11: 559–64

Shand BI, Baily RR, Lynn KL, et al. Effect of enalapril on hemorheology in hypertensive patients with renal disease. Clin Exp Hypertens 1995; 17(4): 689–700

Lo M-W, Toh J, Emmert S, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral losartan in patients with heart failure. J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 38: 525–32

Stearns RA, Chakravarty PK, Chen R, et al. Biotransformation of losartan to its active carboxylic acid metabolite in human liver microsomes. Role of cytochrome P4502C and 3A subfamily members. Drug Metab Dispos 1995 Feb; 23: 207–15

Mallion J-M, Bradstreet DC, Makris L, et al. Antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of once daily losartan potassium compared with captopril in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. J Hypertens 1995; 13Suppl. 1:S35–41

Critchley JAJH, Gilchrist N, Ikeda L, et al. A randomized, double-masked comparison of the antihypertensive efficacy and safety of combination therapy with losartan and hydrochlorothiazide versus captopril and hydrochlorothiazide in elderly and younger patients. Curr Ther Res 1996 May; 57: 392–407

Dahlöf B, Keller SE, Makris L, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of losartan potassium and atenolol in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 1995 Jun; 8: 578–83

Townsend R, Haggert B, Liss C, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of losartan versus enalapril alone or in combination with hydrochlorothiazide in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Ther 1995 Sep–Oct; 17: 911–23

Chan JCN, Critchley JAJH, Lappe JT, et al. Randomised, double-blind, parallel study of the anti-hypertensive efficacy and safety of losartan potassium compared with felodipine ER in elderly patients with mild to moderate hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 1995 Sep; 9: 765–71

Conlin PR, Elkins M, Liss C, et al. A study of losartan, alone or with hydrochlorothiazide vs nifedipine GITS in elderly patients with diastolic hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 1998 Oct; 12: 693–9

Nedogoda S, Petrov V. Enalapril versus losartan at old patients: 24-hour antihypertensive efficacy and influence on quality of life and psychological tests [abstract]. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 52 Suppl.: A86

Farsang C, Garcia-Puig J, Niegowska J, et al. Losartan treatment of patients with isolated systolic hypertension [abstract]. Am J Hypertens 1999 Apr; 12 (Pt 2): 140A

Moore MA, Edelman JM, Gazdick LP, et al. Choice of initial antihypertensive medication may influence the extent to which patients stay on therapy: a community based study of a losartan-based regimen vs usual care. High Blood Press 1998; 7(4): 1–12

Pitt B, Segal R, Martinez FA, et al. Randomised trial of losartan versus captopril in patients over 65 with heart failure (Evaluation of Losartan in the Elderly study, ELITE). Lancet 1997 Mar 15; 349: 747–52

Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Segal R, et al. Losartan heart failure survival study–ELITE II. Circulation 1999 Nov 2; 100 Suppl.: 782 (plus oral presentation)

Dickstein K, Chang P, Willenheimer R, et al. Comparison of the effects of losartan and enalapril on clinical status and exercise performance in patients with moderate or severe chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995 Aug; 26: 438–45

Lang RM, Elkayam U, Yellen LG, et al. Comparative effects of losartan and enalapril on exercise capacity and clinical status in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30: 983–91

Vescovo G, Dalla Libera L, Serafini F, et al. Improved exercise tolerance after losartan and enalapril in heart failure: correlation with changes in skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain composition. Circulation 1998; 98: 1742–9

Warner JJG, Metzger DC, Kitzman DW, et al. Losartan improves exercise tolerance in patients with diastolic dysfunction and a hypertensive response to exercise. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999 May; 33: 1567–72

Cowley AJ, Wiens BL, Segal R, et al. Quality of life in elderly patients with symptomatic heart failure: losartan versus captopril [abstract]. Eur Heart J 1998 Aug; 19 Abstr. Suppl.: 134

Hamroff G, Blaufarb I, Mancini D, et al. Angiotensin II-recep-tor blockade further reduces afterload safely in patients maximally treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1997 Oct; 30: 533–6

Hamroff G, Katz SD, Mancini D, et al. Addition of angiotensin II receptor blockade to maximal angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition improves exercise capacity in patients with severe congestive heart failure. Circulation 1999 Mar 2; 99: 990–2

Hämmerlein A, Derendorf H, Lowenthal DT. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in the elderly: clinical implications. Clin Pharmacokinet 1998 Jul; 35: 49–64

Goldberg AI, Dunlay MC, Sweet CS. Safety and tolerability of losartan potassium, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, compared with hydrochlorothiazide, atenolol, felodipine ER, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for the treatment of systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol 1995 Apr 15; 75: 793–5

ABPI Compendium of data sheets and summaries of product characteristics. London: Datapharm Publications Ltd, 1999

Losartan potassium. AHFS Drug Information 1999. Bethesda (MD): American Society of Health System Pharmacists, 1999: 1609–1610

Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme W, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 709–17

Merck Sharpe & Dohme Ltd.. (Data on file)

Dickstein K, Kjekshus J. Comparison of the effects of losartan and captopril on mortality in patients after acute myocardial infarction: the OPTIMAAL trial design. Am J Cardiol 1999 Feb 15; 83: 477–81

Horiuchi M, Akishita M, Dzau VJ. Recent progress in angiotensin II type 2 receptor research in the cardiovacular system. Hypertension 1999; 33: 613–21

Pitt B. Effects of angiotensin II antagonists in comparison to ACE inhibitors in patients with heart failure due to systolic left ventricular dysfunction. Heart Fail Rev 1999 Feb; 3: 221–32

Burrell LM. A risk-benefit assessment of losartan potassium in the treatment of hypertension. Drug Saf 1997 Jan; 16: 56–65

Joint National Committee on Prevention Detection Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157: 2413–46

Ramsay LE, Williams B, Johnston GD, et al. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the third working party of the British Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens 1999; 13:569–92

Gutkin M. JNC V versus clinical reality: an American practitioner’s perspective. Cardiovasc Rev Rep 1996; 17: 31–5

Gifford JRW, Moser M. Hypertension in the elderly: an update on treatment results and recommendations: a position paper from the council on geriatric cardiology. Am J Geriatric Cardiol 1997 May–Jun; 6: 42–6

Pearce KA, Furberg CD, Rushing J. Does antihypertensive treatment of the elderly prevent cardiovascular events or prolong life? A meta-analysis of hypertension treatment trials. Arch Fam Med 1995; 4: 943–50

CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure.: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1429–35

SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 293–302

Cohn JN, Johnson G, Ziesche S, et al. Acomparison of enalapril with hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate in the treatment of congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 303–10

Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Soprawivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico. GISSI-3: effects of lisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on 6-week mortality and ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1994; 343: 1115–22

Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Effect of ramipril on mortality of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet 1993; 342: 821–8

Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Julius S, et al. Characteristics of 9194 patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. Hypertension 1998 Dec; 32: 989–97

Leidy NK, Rentz AM, Zyczynski TM. Evaluating health-related quality-of-life outcomes in patients with congestive heart failure: a review of recent randomised controlled trials. Pharmacoeconomics 1999 Jan; 15: 19–46

Packer M, Cohn JN. Consensus recommendations for the management of chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1999 Jan; 83Suppl. 2A: 1A–38A

Aronow WS. Treatment of congestive heart failure in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45: 1252–8

Konstam MA, Remme WJ. Treatment guidelines in heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1998; 41Suppl. 1: 65–72

Remme WJ. Towards the better treatment of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1998; 19 Suppl. L: L36–42

Sueta CA, Metts A, Griggs TR, et al. ACE-I use and LV function in the elderly admitted with heart failure: gender differences [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 29: 324A

Sharpe N. Benefit of B-blockers for heart failure: proven in 1999. Lancet 1999 Jun; 353(9169): 1988–9

MERIT-HF Study Group. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999 Jun; 353(9169): 2001–7

CIBIS-II Investigators. The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet 1999; 353: 9–13

Stay on Therapy: the rationale for use of losartan in renal protection. Highlights from a symposium convened at the XVth International Congress of Nephrology, 1999 May 2; Buenos Aires (Data on file, Merck)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simpson, K.L., McClellan, K.J. Losartan. Drugs & Aging 16, 227–250 (2000). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200016030-00006

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200016030-00006