Abstract

Second language (L2) instruction programs often ask learners to repeat aloud words spoken by a native speaker. However, recent research on retrieval practice has suggested that imitating native pronunciation might be less effective than drill instruction, wherein the learner is required to produce the L2 words from memory (and given feedback). We contrasted the effectiveness of imitation and retrieval practice drills on learning L2 spoken vocabulary. Learners viewed pictures of objects and heard their names; in the imitation condition, they heard and then repeated aloud each name, whereas in the retrieval practice condition, they tried to produce the name before hearing it. On a final test administered either immediately after training (Exp. 1) or after a 2-day delay (Exp. 2), retrieval practice produced better comprehension of the L2 words, better ability to produce the L2 words, and no loss of pronunciation quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Advances in technology have made communication, travel, immigration, and other forms of personal exchange across national boundaries ever more feasible and convenient. As a result, people are increasingly likely to be confronted with linguistic diversity, and many aspire to be proficient in more than one language (whether by choice or by necessity). The proliferation of language classes (e.g., English as a Second Language courses around the world) and various language-learning computer software are testaments to the growing desire by many to acquire a foreign language.

In order to acquire mastery over a second language (L2), it is critical for learners to traverse rapidly from a concept that they wish to express and the L2 word(s) appropriate for expressing this concept (or vice versa). In L2 instruction programs, this has often been accomplished by drills in which the learner sees a concept represented either in his or her first language or in pictorial form, hears a native speaker say the word or phrase in the L2, and then tries to imitate. Anyone who has studied a foreign language in the classroom or with audiotapes or CDs will recall hearing “repeat after me” in these drills. Such modeling (by the instructor) and repetition (by the learner) has long been a prominent feature of L2 teaching practices, in traditional classrooms as well as in self-study with audio recordings (Macdonald, Yule, & Powers, 1994; O’Malley, Chamot, Stewner-Manzanares, Kupper, & Russo, 1985). In more recent L2 instruction software (e.g., Berlitz Guaranteed, Pimsleur Method, Linguaphone), this kind of drilling is still often used.

Contemporary language instructors and software designers have attempted to improve instruction by making it more similar to natural language acquisition. For example, the popular Rosetta Stone software provides exercises in which people see images of several objects and hear a spoken L2 word or phrase and then are asked to learn via guessing to match pictures to words. The need to learn via guessing is meant to resemble how children learn new words. In this spirit, because children generally do not learn language by translating to another language, the programs for English users go to great lengths to avoid using any English whatsoever during training. Perhaps viewing imitation as the gold standard in L2 instruction, the Rosetta Stone software also includes a CD that instructs learners to produce L2 words by imitation in additional training sessions. This imitation is done without any reminder or guidance about what the words mean as the learner repeats the utterances (to avoid any use of English).

Relatively little research has contrasted the specific L2 instruction techniques that are commonly in use (although see Carpenter & Olson, 2012), and given the ubiquity of imitation in L2 instruction, it is important to investigate its effectiveness as a pedagogical technique. Some evidence has suggested that imitation plays a role in vocabulary learning. For instance, spontaneous imitation by infants of words spoken by caregivers has been found to predict later vocabulary growth (Masur, 1995). Also, an early study on foreign vocabulary learning showed that saying aloud the L2 vocabulary produced better learning than did studying the items silently (Seibert, 1927). More recently, Ellis and Beaton (1993) found that for English-speaking college subjects learning German vocabulary, repeated imitation (saying aloud) of the German words produced better performance on a later production test (i.e., giving the German equivalent when cued with the English word) than did learning using the keyword mnemonic, which involved visual imagery to associate the English and German equivalents, but no overt production. These findings are consistent with the broader idea that the phonological loop has a critical function in supporting the learning of novel phonological forms, and hence new vocabulary (Baddeley, Gathercole, & Papagno, 1998).

Retrieval practice

The use of imitation, in which learners model their pronunciation on a native speaker’s, might seem particularly suited for promoting native-like pronunciation. The ability to produce accurate pronunciations, however, is by itself insufficient for speaking in a foreign language; one needs to associate the L2 words with the concepts that they express. Many different kinds of evidence have demonstrated that people learn more robust associations when they are required to actively retrieve the association, rather than having both of the associated elements presented together (for a review, see Roediger & Karpicke, 2006). The benefit of retrieval practice (often referred to as the testing effect) has been shown in studies using a wide variety of instructional materials (e.g., prose, word lists, or paired associates). Most relevant for the issue of foreign language vocabulary training are studies that have compared retrieval practice with rereading English–L2 word pairs. For example, Carrier and Pashler (1992) found that producing the English word given an Eskimo (Yupik) cue strengthened the association between the two words more powerfully than did rereading the words paired together (see also Karpicke & Roediger, 2008). In addition, Kang (2010) observed a retrieval practice advantage when the criterial task was to recall (write out) the Chinese logographs (characters) that had been paired with English translations during an initial study phase. These studies suggest that imitation might not be the most efficient way to learn the association between a concept and a word. However, these studies did not require people to pronounce an unfamiliar word. It seems entirely possible that imitation might be useful, and perhaps even optimal, when this difficult form of response learning is required, as it is in L2 learning. Moreover, these studies did not address the possible benefits of imitation—for instance, imitation may lead to better pronunciation than do other forms of practice.

Present study

In two experiments, we compared the relative efficacy of retrieval practice versus imitation for learning L2 words. English-speaking learners were trained on the Hebrew names for 40 common objects. In the imitation condition, the training consisted of hearing the Hebrew name and then repeating it aloud immediately afterward while viewing a picture of the corresponding object. In the retrieval practice condition, the picture was used as a retrieval cue, and learners attempted to retrieve the Hebrew name before the correct pronunciation was provided. Both training conditions, it should be noted, required activity on the part of the learner, and neither was identical to the passive viewing/rereading control conditions that are commonly used in studies of retrieval practice. As compared with silent reading, overt production has been found to improve retention via enhanced distinctiveness of the produced items (e.g., Gathercole & Conway, 1988; MacLeod, Gopie, Hourihan, Neary, & Ozubko, 2010). For the final test, we used two different kinds of assessment. The first involved selecting the appropriate picture (referent) when subjects were presented with the Hebrew word auditorily. The second required production of the Hebrew name when subjects were given a picture of the object. The main differences between the two experiments lay in the amount of training and in the delay before the final test was administered: In Experiment 1, the final test occurred immediately after training; in Experiment 2, training was more extensive, and the final test was given 2 days later. Experiment 2 served two purposes: as a replication of Experiment 1 and for demonstrating that any difference in learning efficacy between the training conditions would persist over a longer delay.

Method

Subjects

Two groups of undergraduates from the University of California, San Diego, Psychology Subject Pool participated in return for course credit: 41 took part in Experiment 1, and 59 in Experiment 2. All of the subjects were fluent speakers of English, and none had any significant prior exposure to Hebrew.Footnote 1

Stimuli

Forty Hebrew nouns served as the to-be-learned foreign vocabulary. Following common practice in foreign language instruction, the words were trained in four lists of thematically related items. Each list contained ten nouns from one of the following four semantic categories: body parts (e.g., ear, hand), eating/food (e.g., fork, bread), animals (e.g., dog, elephant), and household objects (e.g., clock, chair). Across the categories, the Hebrew words were equated in terms of average numbers of syllables (M = 1.95, SD = 0.55) and phonemes (M = 4.65, SD = 1.10). An audio recording of each word was made (spoken by a native Hebrew speaker), and these were presented in the learning and test phases as described below (learners were never presented the written forms of the words, whether in transliterated or Hebrew script). On average, the audio recordings were about 1 s in duration. Four different photographs depicting the referent of each noun (i.e., 40 sets of four photographs) were selected from the Internet; a random three from each set were presented during training, whereas the fourth was used in the final tests. All photographs were standardized to a size of 400 × 400 pixels.

Design

The Hebrew nouns were learned in one of two training conditions—retrieval practice or imitation—that were manipulated within subjects across separate blocks and semantic categories. The subjects’ degrees of learning were assessed after training in two ways: (1) comprehension, in which learners heard each Hebrew word and had to choose the corresponding referent from an array of 40 pictures (representing all of the words learned during training), and (2) production, in which learners were cued with pictures and had to say aloud the corresponding Hebrew words.

Procedure

Learners were tested individually in sound-attenuated rooms. They were seated in front of a computer and wore headphones equipped with a microphone. Learners were informed at the start that they would be learning 40 Hebrew words, divided into sets of ten according to object category. They were also informed about the types of tests that they would be given at the end.

During the training phase, subjects were presented with Hebrew words to learn in four separate blocks, with each block featuring ten words from one of the four semantic categories. Each block began with learners hearing each Hebrew word once, and while each word was played over the earphones, learners saw the appropriate picture (referent) on the computer screen. After the initial presentation, training cycled three times (Exp. 1) or six times (Exp. 2) through all ten words, with the order of items being randomized for each cycle (with the constraint that the first item for each cycle could not be the last item on the preceding cycle). In both training conditions, learners were presented with pictures and audio recordings of the corresponding Hebrew words, with the aim of learning the association between the meaning and pronunciation of each word.

In Experiment 1, the order of the semantic categories across the four blocks was held constant, while the assignment of blocks to training conditions was counterbalanced across learners (either the first two blocks/semantic categories were assigned to retrieval practice and the last two assigned to imitation, or the reverse). In Experiment 2, the assignment of blocks to training conditions was identical to that in Experiment 1, but the order of semantic categories was counterbalanced using a Latin-square design.

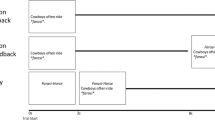

A schematic of the sequence of events in the two training conditions is presented in Fig. 1. For the imitation condition, pictures and audio recordings of the corresponding Hebrew words were both presented, and subjects were asked to imitate what they heard. On each trial, the picture was displayed on the computer screen for 4 s, with the auditory presentation of the Hebrew word beginning at the same time. A 2-s blank interval was inserted between trials. Subjects were instructed to repeat aloud the pronunciation as closely as possible immediately after hearing the Hebrew word, and at the same time to focus on connecting the word to its meaning. For the retrieval practice condition, the presentation of the audio recording of the Hebrew word did not begin until about 3 s after the presentation of the corresponding picture, and learners were asked to try to retrieve and produce the target Hebrew name during the lag. Each trial consisted of the presentation of a picture (on the computer screen) for 4 s, and the timing of the presentation of the audio recording of the Hebrew word was such that the end of the audio recording coincided with the offset of the picture. A 2-s blank interval was inserted between trials. Learners were instructed to attempt the pronunciation of the corresponding Hebrew word when they saw each picture, before the audio recording of the word came online. They were encouraged to guess if they could, but if they could not, they were to wait for the audio recording, and then imitate it immediately after hearing it.

After the training phase, learners received two final tests, both of which were self-paced. In the test of comprehension, learners heard the 40 Hebrew words one at a time, and for each of the words they had to pick the picture that corresponded to the meaning of the word. Displayed on the computer screen were thumbnails of the 40 pictures that had not been presented during training (each corresponding to one of the Hebrew words that had been trained with different pictures), and learners responded by clicking on one of the thumbnails. In the production test, subjects were presented one at a time with the same 40 pictures that were used in the comprehension test, and they tried to produce the corresponding Hebrew word. They were encouraged to guess if they were not sure. Spoken responses were recorded by a microphone. The order of items in each test was randomized for each learner. In Experiment 1, the comprehension test was given first, followed by the production test. In Experiment 2, the order of both tests was counterbalanced across learners,Footnote 2 and a 48-h delay was introduced before the tests were administered. Upon completion of both tests, learners were debriefed and thanked.

Results

Performance was analyzed separately on the comprehension and production tests. The α level for all analyses was set at .05.

Comprehension (accessing semantics when given phonology)

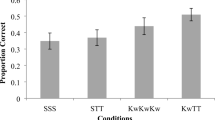

Learners’ ability to select the correct picture/meaning (out of 40 options) when presented with the Hebrew words auditorily was compared across the two training conditions. The retrieval practice condition yielded better performance than did the imitation condition in both experiments, as is shown in Fig. 2. In Experiment 1, this advantage (.63 vs. .57) was marginally significant, t(40) = 1.96, p = .057, d = 0.31. In Experiment 2, the advantage (.57 vs. .44) was significant, t(58) = 3.99, p < .001, d = 0.52.

Production (retrieving phonology when given semantics)

A native Hebrew speaker scored the spoken responses made by learners in their attempts to pronounce the corresponding Hebrew words when presented with the pictures. Since our learners had no preexperimental exposure to Hebrew and were not expected to be able to properly articulate (or perceive) the whole range of Hebrew phonemes (several of which are not present in the English language), we instructed our Hebrew rater to be lenient in the scoring. She listened to the responses blind as to condition and was asked to score them as correct if the pronunciation was good enough that a “native Hebrew speaker would probably be able to understand the word,” even if the pronunciation deviated from what is regarded as an ideal Hebrew pronunciation. For responses that were scored as correct, the rater made an additional judgment of pronunciation quality on a 10-point scale (10 = perfect).Footnote 3

Final test of production

Retrieval practice training yielded more correct productions than did imitation training, as is shown in Fig. 2. In Experiment 1, the advantage of retrieval practice over imitation was significant (.40 vs. .27), t(40) = 3.95, p < .001, d = 0.62. For the responses scored as correct, the pronunciation quality ratings were almost exactly the same (and not significantly different) for the retrieval practice and imitation conditions (5.6 and 5.4, respectively), t < 1. Likewise, in Experiment 2, retrieval practice produced better performance than did imitation training (.34 vs. .19), t(58) = 6.53, p < .001, d = 0.85, and the pronunciation quality ratings for correct responses were again not significantly different across the retrieval practice and imitation conditions (8.2 and 8.0, respectively), t(48) = 1.35, p = .184.

Performance during training

Although it was not the main focus of the present study, we also report production performance during the final cycle of training (i.e., 3rd cycle of practice for Exp. 1, and 6th cycle for Exp. 2). As one would expect, given that in imitation but not in retrieval practice learners had just heard a native speaker produce the target word, performance was better in the imitation than in the retrieval practice condition. In Experiment 1, this difference in proportions correct (.90 vs. .35) was significant, t(40) = 20.92, p < .001, d = 3.27, and for the responses judged as being correct, the pronunciation quality was also higher in the imitation than in the retrieval practice condition (6.5 vs. 5.7), t(40) = 3.70, p = .001, d = 0.58. Similarly, in Experiment 2, the difference in proportions correct (.90 vs. .55) was reliable,Footnote 4 t(49) = 10.51, p < .001, d = 1.49, and the pronunciation quality of correct responses was higher in the imitation than in the retrieval practice condition (8.2 vs. 7.6), t(49) = 4.05, p < .001, d = 0.57.

Discussion

The experiments reported here contrasted two different ways of learning L2 vocabulary. The first was the retrieval practice procedure, modeled after traditional flashcard-type drills, which required the learner to produce (say aloud) the L2 word when cued by the concept (presented in the form of a picture), followed by presentation of the correct answer. The second was the imitation procedure modeled after practice drills commonly found in language instruction programs; here, the learner viewed a picture of the referent of the word and repeated aloud a native speaker’s pronunciation of the word. In two experiments, the retrieval practice procedure proved robustly superior to the imitation procedure.

Although prior research has demonstrated the advantage of retrieval practice in learning L2 vocabulary, those studies almost exclusively used a (passive) rereading control condition and assessed learners’ ability to recall the English translations (presumably due to the ease of scoring English responses). Our study is the first to have examined the effects of retrieval practice on learning of L2 phonological word forms. Focusing on learning of these unfamiliar sound sequences (as opposed to learning familiar English responses) provides a powerful demonstration of the versatility of retrieval practice and has significant theoretical and practical implications (discussed below). Furthermore, one could reasonably expect when learning difficult, unfamiliar responses that imitation practice would be advantageous, especially in the early stages of learning (i.e., a potential boundary condition for the testing effect), or that any benefits of retrieval practice would come at the expense of poorer pronunciation quality. Our findings, however, disconfirm these suggestions.

Theoretical implications

One potential explanation for the observed superiority of retrieval practice over imitation is that the former engages the same sorts of mental operations that are required on the final production test (in both cases, the learner is cued with a picture and has to retrieve and produce the appropriate L2 word). This line of reasoning is consistent with the transfer-appropriate processing framework, which proposes that performance is optimized when the processes required at test overlap with those recruited during learning (Morris, Bransford, & Franks, 1977). It should be noted, however, that the advantage of retrieval practice was not limited to the criterial test that most resembled the retrieval practice training procedure. The benefits extended to a reception test that assessed learners’ listening comprehension of the L2 words. The fact that retrieval practice can enhance learning even when the criterial test differs from the testing procedure used in training has been observed in past studies of learning from prose passages (McDaniel, Anderson, Derbish, & Morrisette, 2007), maps (Rohrer, Taylor, & Sholar, 2010), and paired-associate learning (Carpenter, Pashler, & Vul, 2006).

The present results are also consistent with the neural-network model of test-enhanced learning proposed by Mozer, Howe, and Pashler (2004). According to this model, learning entails a comparison between a desired output and the actual output, upon which the connections between input and output units are adjusted so as to reduce the discrepancy between the desired and actual outputs. When the cue and target are presented together (imitation condition), the error correction mechanism is short-circuited, reducing the efficiency of learning. But when the network is allowed to produce a response to a cue and then receives feedback (retrieval practice condition), error correction is facilitated and the learning system reaches the desired state more quickly.

Some recent accounts of the testing effect have emphasized the role of mediators in promoting later retrieval of the target. For instance, when one is presented with a cue (e.g., donor–?) and attempts retrieval, there is a greater tendency for information related to the cue to become activated (e.g., blood) than when one merely rereads the cue–target pair (donor–heart), and the activated information then serves as an effective mediator for subsequent retrieval (Carpenter, 2011). When subjects are explicitly instructed to generate mediators (between cues and targets), evidence also shows that retrieval failures during practice encourage a shift to more effective mediators (Pyc & Rawson, 2012), thus improving later retrieval. However, these studies involved target responses that were English words; it is unclear how mediators could be generated (whether spontaneously or deliberately) to support the retrieval or production of unfamiliar Hebrew words.

Practical considerations

We found numerically larger effect sizes in the criterial tests of production (cf. comprehension). Given that productive abilities in language learning generally lag behind (or are more difficult/slower to acquire than) receptive abilities, it is noteworthy that retrieval practice produced especially robust gains in the more difficult task (i.e., from meaning to L2 phonology; e.g., Kroll & Stewart, 1994; Schneider, Healy, & Bourne, 2002). When considering various procedures for use in training, presumably an ideal candidate would be one that enhances learning in more challenging (or harder-to-learn) domains.

Why, then, is imitation so popular a learning strategy in L2 instruction programs? One possibility is that designers of training programs often assume that conditions that optimize performance during training are the conditions that best promote the goals of training—that is, long-term posttraining performance (Bjork, 1994). Indeed, if performance during training were the determining criterion, imitation would seem to be an ideal training procedure, as evidenced by the near-ceiling production accuracy and quality (during imitation training) found in our experiments. However, procedures that yield quick acquisition and high performance during training often produce illusions of competence, and may not support durable learning and performance in the long term. A more effective way to encourage long-lasting learning is to incorporate desirable difficulties during training (Bjork, 1999), of which retrieval practice is one example.

Of course, our results do not imply that imitation practice is a completely futile strategy for L2 learning (see Ellis & Beaton, 1993), nor that L2 instruction programs rely on imitation as their sole pedagogical strategy (in fact, many programs include some time spent on some form of testing/retrieval practice). However, given that the present findings unambiguously demonstrate a more effective method of training than imitation—one that requires only a subtle modification in training procedure, without any increase in training time—we contend that for L2 vocabulary learning, imitation should not be automatically assumed to be the tried and true instructional procedure. On the basis of our data, it would appear that time spent imitating a native speaker’s utterance could be much better spent engaging in retrieval practice with corrective feedback on pronunciation.

Notes

The majority of our subjects reported using at home either a non-English language or a non-English language in combination with English (only four and six subjects in Exps. 1 and 2, respectively, reported having an English-only home environment). To examine whether subjects’ language backgrounds modulated the results, we performed additional analyses in which three language background variables (age of exposure to English, primary language used at home, and speaking proficiency in one’s non-English language) were included as factors in the ANOVAs. None of these factors interacted significantly with the main factor Training Condition.

The order of types of test did not have any effect, and therefore is not discussed further.

The final production test data from a random 28 of the subjects (13 and 15 subjects from Exps. 1 and 2, respectively) were scored for accuracy by a second native Hebrew speaker (who was blind as to condition), and the interrater agreement was high (Cohen’s κ = .82).

Due to equipment malfunction, some of the spoken responses during training for nine subjects were lost, and hence data from those subjects were excluded from the analysis.

References

Baddeley, A., Gathercole, S., & Papagno, C. (1998). The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychological Review, 105, 158–173. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.105.1.158

Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 185–205). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bjork, R. A. (1999). Assessing our own competence: Heuristics and illusions. In D. Gopher & A. Koriat (Eds.), Attention and performance XVII: Cognitive regulation of performance: Interaction of theory and application (pp. 435–459). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Carpenter, S. K. (2011). Semantic information activated during retrieval contributes to later retention: Support for the mediator effectiveness hypothesis of the testing effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37, 1547–1552. doi:10.1037/a0024140

Carpenter, S. K., & Olson, K. M. (2012). Are pictures good for learning new vocabulary in a foreign language? Only if you think they are not. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38, 92–101. doi:10.1037/a0024828

Carpenter, S. K., Pashler, H., & Vul, E. (2006). What types of learning are enhanced by a cued recall test? Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 13, 826–830. doi:10.3758/BF03194004

Carrier, M., & Pashler, H. (1992). The influence of retrieval on retention. Memory and Cognition, 20, 633–642. doi:10.3758/BF03202713

Ellis, N., & Beaton, A. (1993). Factors affecting the learning of foreign language vocabulary: Imagery keyword mediators and phonological short-term memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 46A, 533–558. doi:10.1080/14640749308401062

Gathercole, S. E., & Conway, M. A. (1988). Exploring long-term modality effects: Vocalization leads to best retention. Memory and Cognition, 16, 110–119. doi:10.3758/BF03213478

Kang, S. H. K. (2010). Enhancing visuospatial learning: The benefit of retrieval practice. Memory and Cognition, 38, 1009–1017. doi:10.3758/MC.38.8.1009

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319, 966–968. doi:10.1126/science.1152408

Kroll, J. F., & Stewart, E. (1994). Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connection between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Language, 33, 149–174. doi:10.1006/jmla.1994.1008

Macdonald, D., Yule, G., & Powers, M. (1994). Attempts to improve English L2 pronunciation: The variable effects of different types of instruction. Language Learning, 44, 75–100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01449.x

MacLeod, C. M., Gopie, N., Hourihan, K. L., Neary, K. R., & Ozubko, J. D. (2010). The production effect: Delineation of a phenomenon. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36, 671–685. doi:10.1037/a0018785

Masur, E. F. (1995). Infants’ early verbal imitation and their later lexical development. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 41, 286–306.

McDaniel, M. A., Anderson, J. L., Derbish, M. H., & Morrisette, N. (2007). Testing the testing effect in the classroom. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19, 494–513. doi:10.1080/09541440701326154

Morris, C. D., Bransford, J. D., & Franks, J. J. (1977). Levels of processing versus transfer appropriate processing. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16, 519–533. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(77)80016-9

Mozer, M. C., Howe, M., & Pashler, H. (2004). Using testing to enhance learning: A comparison of two hypotheses. In K. Forbus, D. Gentner, & T. Regier (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 975–980). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

O’Malley, J. M., Chamot, A. U., Stewner–Manzanares, G., Kupper, L., & Russo, R. P. (1985). Learning strategies used by beginning and intermediate ESL students. Language Learning, 35, 21–46. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1985.tb01013.x

Pyc, M. A., & Rawson, K. A. (2012). Why is test–restudy practice beneficial for memory? An evaluation of the mediator shift hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38, 737–746. doi:10.1037/a0026166

Roediger, H. L., III, & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). The power of testing memory: Basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 181–210. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x

Rohrer, D., Taylor, K., & Sholar, B. (2010). Tests enhance the transfer of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36, 233–239. doi:10.1037/a0017678

Schneider, V. I., Healy, A. F., & Bourne, L. E., Jr. (2002). What is learned under difficult conditions is hard to forget: Contextual interference effects in foreign vocabulary acquisition, retention, and transfer. Journal of Memory and Language, 46, 419–440. doi:10.1006/jmla.2001.2813

Seibert, L. C. (1927). An experiment in learning French vocabulary. Journal of Educational Psychology, 18, 294–309.

Author note

S.H.K.K. is now at the Department of Education, Dartmouth College. This work was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences (US Department of Education, Grant No. R305B070537 to H.P.), the National Science Foundation (Grant No. BCS-0720375, H.P., PI; and Grant No. SBE-0542013, G. W. Cottrell, PI), a collaborative activity award from the J. S. McDonnell Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health (Grant Nos. NIDCD 011492 and NICHD 050287, T.H.G., PI). We acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals: Jeff Estacio programmed the experiment; Noriko Coburn assisted with data collection; and Shira Cabir, Efrat Golan, and Ronit Snyder scored our subjects’ oral pronunciations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, S.H.K., Gollan, T.H. & Pashler, H. Don’t just repeat after me: Retrieval practice is better than imitation for foreign vocabulary learning. Psychon Bull Rev 20, 1259–1265 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-013-0450-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-013-0450-z