Abstract

Beyond the increasing quality of car technology in the last decade, road and fast-paced city traffic in metropolises still impose high accident rates. Mostly, drivers’ inattentiveness, tiredness or just bad driving abilities are responsible for safety risks. Novel developments such as the combination of in-vehicle systems and vehicle sensors in the environment could lower these risks. While on the one hand the V2X-technologies bare a huge potential for safety and efficiency, on the other hand, the missing trust and concerns about privacy could represent major obstacles for a successful implementation. Hence, historically, trust in new technology is a major issue, which need to be integrated into the technological development. The perceived trust and control in the field of V2X-technology, with a focal point on automated driving, is the main research focus. Using a quantitative approach, users were examined regarding their perception of V2X-technologies. Results reveal an obvious reluctance towards V2X-technologies, independent of user diversity. Data disclosure of personal data is mostly denied homogeneously. Findings hint at a considerable need for a sensitive and individually tailored information and communication strategy regarding V2X-technology.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Vehicle2x (V2X) communication

- Car2x (C2X)

- Vehicular ad hoc network (VANET)

- Intelligent transportation systems (ITS)

- Trust

- Control

- Privacy

- Technology acceptance

- Data handling

1 Introduction

The number of fatalities in traffic situations in Europe is decreasing, but with a total of over 28.000 (in 2012) still not even close to acceptable [1]. In addition, congestion and pollution are also hazards, which need to be taken into account. Therefore, the increasingly aging society needs new strategies in the everyday traffic infrastructure. This is necessary for using all the various mobility options we have today: bus, train, metro or personal car. A combination of in-vehicle systems and vehicle sensors is expected to take part in solving these problems and lowering risks of accidents. Over the last thirty years, this technology was integrated in an automated train operation (ATO) in different countries, like France, Germany or the United States [2]. Now, Sweden started their “Drive Me” project with 100 self-driving cars. The vehicles are able to follow the lane, adapt speed and merge traffic on their own - V2X-technology on public roads with everyday driving situations [3]. A major V2X-center is built since 2014 in Germany (namely the Center for European Research on Mobility, RWTH Aachen University), which will investigate the technology and the user acceptance further.

Those technical solutions are assumed to result in a more efficient and safer transport system by offering the driver a more detailed view of prevailing traffic situations [4]. Another technical solution refers to the connection of transportation means, which can create new opportunities for mobility and be part of the increasing efficiency in traffic [5]. By an exchange of information on the technical level between different road users (cars, signal systems, or intelligent sensor technology in the road surface), a cooperative environment is created, in which an assessment of current traffic situations can be based on more information than there would be available for a single, isolated traffic participant. The more complete situation awareness may be used for an increase of security, for a more energy efficient driving or traffic management. If a traffic situation necessitates a reaction, vehicles or road infrastructure can address this issue either by an autonomous response (takeover of control by the system), or by assisting the human driver by information delivered by the vehicle system (driver control, but information and communication assistance). This could also lead to a safer and easier way of driving, which also feels more relaxing. To achieve such possibilities it is inevitable that the driver is comfortable with handing over control to an automated system [6]. A driver needs to trust the system in order to give up control over a vehicle or the situation. That trust in the technology needs to come from both, the service provider and the user [7].

Hence, the weakening of such positive effects of automation has been identified as e.g. situation awareness [8], misuse or abuse of the technology [9] or over reliance on automation [10]. Further, it is indispensable that users learn about limitations of the technology. As shown in [11], without full knowledge, the over reliability and therefore quickly given trust of drivers in automated systems (adaptive cruise control (ACC)) concluded in collisions. As a result, the increase of information that has to be presented at a time to drivers raises new usability questions. Moreover, acceptance concerns arise: both the sharing of information that may encourage the tracking of users and the possible withdrawal of control may result in privacy and trust issues. Therefore, the consideration of users’ abilities, requirements and needs during research and development of future V2X-technology is indispensable in order to reach a positive public perception. While usability issues in traditional in-vehicle system are even more considered due to the increasing integration of multimedia functions [12], in contrast, user-centered research on V2X-communication is still at an early stage. Rudimentary knowledge about the intention to use early V2X-prototypes with, for example, congestion warning functionality or traffic light assistance was already achieved by the COOPERS- and the simTD-project in both simulator and field trials [13, 14].

Hence, trust in and acceptance of V2X-technology is insufficiently explored if not ignored so far. Little is known about the perceived control and risk in driving behaviour or the willingness to share information within transport systems or networks.

Recent work about trust concerns in technology research is wide-ranging, e.g. the various disciplines working on the field of medical devices [15, 16] or car-related topics [6, 17]. Also large enterprises like Google or Volvo have projects on the topic of automation and already started testing self-driving cars [3, 18].

Trust as crucial psychological factor is analysed in all of the following studies throughout the last decades [19–23]. Another study concerning trust in automated cruise control [24] showed that information providing ACCs are perceived more trustworthy by take-over actions than ACCs which take over control without giving the driver information about it. This finding lines to the research of reported by [6], which reported that implications on information is still discussed.

Hence, information and data exchange is a crucible factor in trust-related research, which is why the current study sets a focus on the willingness of the user to share data with an intelligent (V2X-technology) driving assistance. As a key variable for reliance and misuse of automated systems, trust is defined as “…the attitude that an agent will help achieve an individual’s goals in a situation characterised by uncertainty and vulnerability” ([23], p. 51). It can be improved by (driving) experience and/or practise with automated systems. However, if the automation fails it entails a decline of trust [23]. A trial and error strategy was tested [25] and concluded as insufficient for building a trust model. Expectations in the systems should also be communicated, as well as the level of information given to the user [23, 25].

2 Method

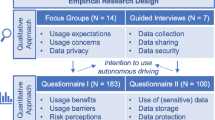

Using an online survey, we explored users’ attitudes towards perceived control and risks, also their willingness to share data as well as opinions with respect to conditions of data handling and storage. Also, a general evaluation of V2X-technologies was collected. Addressing user diversity, we examined age and gender as well as different levels of need of control as an individual trait (Fig. 1).

2.1 Questionnaire

In the questionnaire, the trustworthiness in in-vehicle systems and automated driving systems was focused. Traffic situations, which were identified recently [26], were taken as exemplary scenarios. The survey contained the following sections.

Demographic Data. The first part of the questionnaire dealt with demographical data like gender, age and educational level.

Trust and Control in Traffic Situations. The second part introduced beforehand identified traffic scenarios to let the participants envision the active use of V2X-technology (e.g. intersection scenario). A set of different questions about personal data, trust and usefulness of V2X-technology followed (Table 1).

The section closes with questioning duration, storage and handling of the collected information about the user or the vehicle (Table 2).

Vehicle-to-X Technology Evaluation. A set of items questioned a general evaluation of V2X-technology (Table 3).

2.2 Sample

Overall, 110 participants took part in this survey. The age range spans from 21 to 66 years (M = 31.5; SD = 10.7). Subjects were divided into four age/mobility need groups: young students (21-25 y., n = 32), young professionals (26-29 y., n = 34), middle-aged professionals (30-40 y., n = 28) and professional experienced (41+ y., n = 16). 67 % men (n = 74) and 33 % women (n = 36) took part. The sample was well educated: 70.9 % had a university degree (n = 78), followed by 18.2 % with a technical college degree (n = 20) and 6.4 % (n = 6) did vocational training plus 4.5 % stated other level of education. For further research, users had to classify themselves according to personal risk or control attitudes: risk-group (n = 39), control-group (n = 89).

3 Results

Data was analyzed by parametric statistical evaluation methods. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare groups. The significance level was at p = .05. First we report the general evaluation of V2X technology. The next section is concerned with perceptions on data collection and management, thereby contrasting different data in different sensibilities. Then we report, if there are certain trade-offs in the sensibility of data handling and storage within V2X-technologies; and more detailed, if there are specific situations that are mostly denied while other usage contexts are tolerated. Despite the fact, that the level of disagreement has a strong individual component, we categorized subjects into “Yes-persons” - those being open minded to “V2X open data management” - and into “No-persons” - those who reported to stay disclosed. Also, the conditions for data storage like duration and handling are described.

3.1 General Evaluation of V2X

In a first step, we report on general attitudes towards V2X-technologies (for items see Table 3). As can be seen from Fig. 2, the highest confirmation was found for the need of continuous control over the technology (M = 3.8; SD = 1.5). The next most prominent items are the perceived usefulness of V2X-technology (M = 3.7; SD = 1.6) and the credo that V2X-technology needs a high level of regulation and control (M = 3.7; SD = 1.6).

The question whether V2X-technologies are perceived as threatening was mostly denied (M = 1.4; SD = 1.3). Looking at diversity effects, neither age nor gender did impact the evaluations. Also, the segregation of participants in control-group and risk-group did not make any significant difference for the general evaluation. From this we conclude that the evaluations here represent a quite homogeneous attitude of participants, not impacted by different roles (gender) or biographical points in time (age), not even by different levels of control vs. risk habits of users.

3.2 Perceptions on Data Collection and Data Management

Another important issue in the context of V2X-technology is the question which data might be collected and stored. We presented a set of possible information that could be collected in the actual traffic in order to get a comprehensive picture. Among those there are options that refer to external/distant events (traffic) and options that come close to the person/body (physiological data). Participants were requested to indicate their openness to share the respective within V2X-technology (data disclosure). Descriptive findings can be taken from Fig. 3.

Among the more uncritical information, which participants would mostly agree on sharing is the type of road user (M = 3.9; SD = 1.6) and the current motion data (M = 3.6; SD = 1.6). Participants are willing to disclose data about their movement direction to a lesser extent (M = 2.7; SD = 1.7) and also data about vehicle specifications (M = 2; SD = 1.9). There is overall less willingness to share information about past trips (M = 1.6; SD = 1.7). Most critical are demographic data (M = 0.8; SD = 1.4), other personal data (M = 0.7; SD = 1.1) or even a person’s physiological status (M = 0.6; SD = 1). User diversity, again, did not show any single significant influence on the evaluation here. Neither the degree of the self-attributed control vs. risk type, nor age and gender did impact the willingness to share data. We learn from this that there is a considerable susceptibility on the one hand and selectivity on the other hand with respect to the data that may be collected in live traffic.

However, the analysis does not tell something about the individual answering styles so far. In a next step further analyses were run. One analysis refers to the subjects, which denied collection and storage and those that agreed in the respective data contexts. We divided the sample into two groups: one contained negative answers (black bars) and one positive responses (grey bars). Outcomes can be found in Fig. 4.

What can be seen here is a kind of “sensitivity” curve, a trade-off between “yes” and “no” decisions: With decreasing distance to a person, the level of disagreement to disclose data increases. Again, it is astounding how stable the decisions are for the overall group: no gender and age effects showed up as well as no personal needs for risk vs. control effects. If a fair (50 %) cut-off would be applied, only three data contexts reach a higher percentage of yes than no (namely: data on road users, motion data, and direction of movement). In all other contexts the “no fraction” is higher than the “yes fraction”.

The other analysis regards the question, whether the data context is predominately impacting the “yes” or “no” decision or rather personal habits (“Yes”/“No” persons). This hypothesis was underpinned by highly significant inter correlations (see Table 4).

Thus, whenever users agreed to disclose data in one context they also tend to agree in other contexts (with few exceptions) and vice versa. This hints at a quite clear-cut personal style to disclose data or not.

Based on this, we analyzed how many persons denied data disclosure in how many contexts (despite of the context, just summarized).

What can be seen from Table 5 is, 11 % of the participants showed a very open-minded attitude to share data (subjects, which agreed in most cases) and considerable 31 % were quite reluctant or rather negative when it comes to sharing data in the V2X context.

3.3 Conditions of Data Storage

Another critical issue for the public is how long which type of data may be stored and which authority may be allowed to store it. Basically, the participants had to indicate the tolerated duration of data storage (only capturing and processing vs. short-term vs. permanent storage) and the authority, which should be allowed to store it (local road users vs. local infrastructure vs. central traffic management vs. companies). Figure 5 shows the findings.

As can be seen from Fig. 5, another important issue is the authority, which is in duty of the data storage. Outcomes clearly indicate that a more central (and out of persons’ control) location of the server (public authority, or, company) equals a lower openness of participants. Furthermore, long-term storage is generally disliked, independent of which authority might be in duty of data handling and storage.

4 Discussion and Outlook

The study was directed to an understanding of public perceptions regarding automated car traffic and V2X-communication. While V2X-technology gains increasing research attention with respect to technical issues [31, 32], so far sparse knowledge is prevailing about public perception and acceptance of passing over the control to the car, especially when the use case requires a higher degree of automation.

Based on an earlier study [26], which explored acceptance issues (perceived benefits and barriers of V2X-technology), this research concentrated specifically on data privacy and trust in V2X-technology. In order to get a first impression of the prevailing perceptions in this regard, we used a highly technology prone and well-educated sample. As V2X-technologies may be used for a general increase in road safety and effectiveness, they are also especially useful for integrating older road users (e.g. stay mobile at older age, assisting older drivers with medical monitoring during driving), the sample had a wide age range.

In contrast to many other recent studies on technology acceptance in a novel technological field [15, 16], for V2X-technologies were no effects of user diversity identified. Neither age nor gender did affect the evaluations, and also not the personal trait to seek for control vs. risk. Overall, the evaluations were rather homogeneous, at least in this highly educated sample. This is especially notable; as there is substantial empirical evidence that technology acceptance is impacted by the experience with technology, the domain knowledge and technical self-confidence and also with risk perceptions that correlate with gender [27]. Apparently, the question of data disclosure in V2X-technology and the general concerns about protection of intimacy and the fear of losing privacy is dominant and deeply anchored, at least in the western culture to which the sample belongs to [28]. In this context, studies reported on the privacy paradox [29, 30], which is characterized by individuals’ intention to information disclosure on the one hand and the willingness to be profiled in cyberspace on the other.

For V2X-technologies (and this was shown here), there is a broad reluctance and aloofness of users to share data. The reluctance is higher the more personal the information is. Or other way round: with decreasing distance to the body (in case of physiological data) or the person (demographics), the level of disagreement to disclose data increases. It is an interesting finding that V2X-technologies seem to cut the sample into two different and diametrical parts. While there is a small group of persons that is willing to share V2X-data (quite irrespective in which context), a larger part is refusing data disclosure (also quite irrespective of the context).

We cannot explain the nature of these two opposite answering styles, or personal attitudes on the basis of the present data. Here, future studies will have to find out, if these perceptions might change in other user groups. In this context, other education levels come into fore as well as a higher experience with V2X-technology. It is most likely that persons without personal experience with a technology tend to overestimate the “risk” or the “threatening” nature of the novel technology and that this might fade with increasing familiarity [16, 27].

Nevertheless, from a social science point of view it is of utmost importance to consider users’ perceptions and to integrate users’ requirements and information and communication needs in early stages of technology development, in order to shape a sensible information and communication strategy thus to support a broadly accepted attitude towards V2X-technologies in Germany.

References

European Commision - Directorate General Energy and Transport: Road safety evolution (2014). http://ec.europa.eu/transport/road_safety/pdf/observatory/historical_evol.pdf

Erbin, J.M., Soulas, C.: Twenty years of experiences with driverless metros in France. VWT19, pp. 1–33 (2003)

Volvo Car Group’s first self-driving Autopilot cars test on public roads around Gothenburg (2014). https://www.media.volvocars.com/global/en-gb/media/pressreleases/145619/volvo-car-groups-first-self-driving-autopilot-cars-test-on-public-roads-around-gothenburg

Van Driel, C.J.G.: Driver support in congestion: an assessment of user needs and impacts on driver and traffic flow (2007)

Picone, M., Busanelli, S., Amoretti, M., Zanichelli, F., Ferrari, G.: Advanced Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems. Springer, New York (2015)

Helldin, T., Falkman, G., Riveiro, M., Davidsson, S.: Presenting system uncertainty in automotive uis for supporting trust calibration in autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, pp. 210–217. ACM, New York (2013)

Duri, S., Gruteser, M., Liu, X., Moskowitz, P., Perez, R., Singh, M., Tang, J.-M.: Framework for security and privacy in automotive telematics. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Mobile Commerce, pp. 25–32. ACM (2002)

Endsley, M.R.: Automation and situation awareness. In: Parasuraman, R., Mouloua, M. (eds.) Automation and Human Performance Theory and Applications, pp. 163–181. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah (1996)

Parasuraman, R., Riley, V.: Humans and automation: use, misuse, disuse, abuse. Hum. Factors 39, 230–253 (1997)

Parasuraman, R., Manzey, D.H.: Complacency and bias in human use of automation: an attentional integration. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 52, 381–410 (2010)

Stanton, N.A., Young, M., McCaulder, B.: Drive-by-wire: the case of driver workload and reclaiming control with adaptive cruise control. Saf. Sci. 27, 149–159 (1997)

Harvey, C., Stanton, N.A.: Usability Evaluation for In-vehicle Systems. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2013)

Böhm, M., Fuchs, S., Pfliegl, R., Kölbl, R.: Driver behavior and user acceptance of cooperative systems based on infrastructure-to-vehicle communication. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2129, 136–144 (2009)

simTD - Sichere Intelligente Mobilität Testfeld Deutschland: Projektergebnis (2013). http://www.simtd.de/index.dhtml/object.media/deDE/8127/CS/-/backup_publications/Projektergebnisse/simTD-TP5-Abschlussbericht_Teil_B-2_Nutzerakzeptanz_V10.pdf

Ziefle, M., Röcker, C., Holzinger, A.: Medical technology in smart homes: exploring the user’s perspective on privacy, intimacy and trust. In: 2011 IEEE 35th Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference Workshops, pp. 410–415. IEEE (2011)

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M.: Privacy and data secrurity in e-health: requirements from users’ perspective. Health Inform. J. 18(3), 191–201 (2012)

McGuirl, J.M., Sarter, N.B.: Supporting trust calibration and the effective use of decision aids by presenting dynamic system confidence information. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 48, 656–665 (2006)

Google Inc.: Google Self-Driving Car Project (2015). https://plus.google.com/+GoogleSelfDrivingCars

Lee, J., Moray, N.: Trust, control strategies and allocation of function in human-machine systems. Ergonomics 35, 1243–1270 (1992)

Muir, B.M.: Trust in automation: Part I. Theoretical issues in the study of trust and human intervention in automated systems. Ergonomics 37, 1905–1922 (1994)

Muir, B.M., Moray, N.: Trust in automation. Part II: Experimental studies of trust and human intervention in a process control simulation. Ergonomics 39, 429–460 (1996)

Lewandowsky, S., Mundy, M., Tan, G.: The dynamics of trust: comparing humans to automation. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 6, 104 (2000)

Lee, J.D., See, K.A.: Trust in automation: designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 46, 50–80 (2004)

Verberne, F.M., Ham, J., Midden, C.J.: Trust in smart systems sharing driving goals and giving information to increase trustworthiness and acceptability of smart systems in cars. Hum. Factors 54, 799–810 (2012)

Beggiato, M., Krems, J.F.: The evolution of mental model, trust and acceptance of adaptive cruise control in relation to initial information. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 18, 47–57 (2013)

Schmidt, T., Philipsen, R., Ziefle, M.: Safety first? V2X – Percived benefits, barriers and trade-offs of automated driving. Full paper submitted to the International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems (Vehits 2015)

Ziefle, M., Schaar, A.K.: Gender differences in acceptance and attitudes towards an invasive medical stent. Electron. J. Health Inform. 6, e13 (2011)

Whitman, J.Q.: The two western cultures of privacy: dignity versus liberty. Yale Law J. 113, 1151–1221 (2004)

Awad, N.F., Krishnan, M.S.: The personalization privacy paradox: an empirical evaluation of information transparency and the willingness to be profiled online for personalization. MIS Q. 30, 13–28 (2006)

Norberg, P.A., Horne, D.R., Horne, D.A.: The privacy paradox: Personal information disclosure intentions versus behaviors. J. Consum. Aff. 41(1), 100–126 (2007)

Ardelt, M., Coester, C., Kaempchen, N.: Highly automated driving on freeways in real traffic using a probabilistic framework. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 13(4), 1576–1585 (2012)

Lefevre, S., Petit, J., Bajcsy, R., Laugier, C., Kargl, F.: Impact of v2x privacy strategies on intersection collision avoidance systems. In: IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference, Bosten, USA (2013)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Also, we owe gratitude to the research group on mobility at RWTH Aachen University, which works on the interdisciplinary CERM project (supported by the Excellence Initiative of German State and Federal Government). Many thanks go also to Julia van Heek for her valuable research input.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Schmidt, T., Philipsen, R., Ziefle, M. (2015). From V2X to Control2Trust. In: Tryfonas, T., Askoxylakis, I. (eds) Human Aspects of Information Security, Privacy, and Trust. HAS 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9190. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20376-8_51

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20376-8_51

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20375-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20376-8

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)