Abstract

The literature on school entry laws has shown that relative school starting age affects smoking behavior and health in adolescence, yet it remains unclear whether these effects persist into adulthood. Filling this gap, we analyze the long-term effects of relative school starting age on smoking behavior and health in adulthood. This study employs a fuzzy regression discontinuity design, using school entry rules combined with birth month as an instrument for school starting age. The analysis adopts data from the German Socio-Economic Panel. The results reveal that an increase in relative school starting age significantly reduces the long-term risk of smoking, improves long-term health, and affects physical rather than mental health. Several robustness checks confirm these results. In addition, we present suggestive evidence that the relative age composition of peers and the school environment are important mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The World Health Organization standardizes national smoker rates by applying age-specific smoker rates by sex in each population to a statistical standard population to enable cross-country comparisons.

This branch of literature and our study exploit legal school starting age cutoffs to analyze the effects of relative differences in individual school starting age. By contrast, Fletcher and Kim (2016) analyze the effects of shifts in school entry cutoffs that change the absolute school starting age.

These studies interpret the higher number of diagnoses among younger school starters as misdiagnoses, which is confirmed by Dalsgaard et al. (2012).

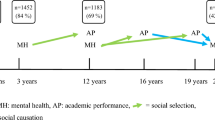

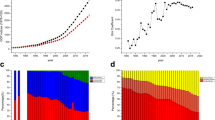

Figures 1 and 2 are based on data from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS), 2003–2006, administered by the Robert Koch Institute. KiGGS is a nationwide clustered random sample of 17,641 children and adolescents (0–17 years) and their parents (Hölling et al. 2012).

Biewen and Tapalaga (2017) analyze life-cycle educational choices in Germany and give an overview of the German education system.

We neglect repeated observations for two reasons. First, Eibich (2015) and Godard (2016) show that retirement reduces the likelihood of smoking and improves health; thus, including observations close to retirement might bias the estimated effects of school starting age. Second, selective sample attrition will likely become an issue if older observations are included in the sample because unhealthy individuals are more likely to drop out of the sample than healthy individuals. However, the robustness checks show that the main results are robust to both the inclusion of all available observations for each respondent and exclusion of respondents at least 60 years old.

“Quasi-objective” means that the respective health measure enables health comparisons across different groups of persons (e.g., age groups).

We use the absolute school starting age rather than the relative school starting age. Although we use an absolute measure, our approach reflects the effects of one’s individual school starting age relative to that of class and school peers. This approach is in line with the literature on school starting age effects (e.g., Bedard and Dhuey 2006; Fredriksson and Öckert2014).

Before the German reunification in 1990, the starting month differed by federal state. Before 1964, the starting month in the Federal Republic of Germany was April or August. However, in 1964, the Hamburger Abkommen harmonized the start of primary school to August 1st. The starting month in the German Democratic Republic was September 1st but in 1990, it was also changed to August 1st.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, some federal states had school entry cutoffs other than June 30th (about 21% of the sample), although this was later harmonized with the ratification of the Hamburger Abkommen on October 28, 1964. Before the German reunification in 1990, the school entry cutoff in the German Democratic Republic was May 31st (about 21% of the sample). Thus, the June 30th cutoff is relevant for about 58% of the sample. The following analyses include observations from all cutoffs.

Respondents who started school in the former GDR are assigned a GDR indicator.

Modeling higher degree polynomials of the running variable is infeasible in this application, because the running variable is discrete rather than continuous.

Staiger and Stock (1997) suggest that an F statistic of larger than 10 suffices.

In Table 2, only few specifications show small statistically significant differences in the share of people with migration background, the share of mothers with higher secondary school degrees and fathers with lower secondary school degrees. However, these differences are statistically significant only at the 10% level in few specifications and are statistically non-significant in the large majority of specifications. Adding further validity to the approach, Table 12 in the Appendix shows that a father’s and mother’s age and occupational prestige are also balanced around the cutoff.

The values for school degree type do not aggregate to 100% because some respondents’ parents have other or unspecified types of school degrees.

The difference in the physical health score is divided by 10, which is the variable’s standard deviation in the initial calibration of the SF12 score in the 2004 SOEP sample.

Black et al. (2011) find that school starting age has a significant, but small effect on the mental health of 18–20-year-old males, using Norwegian military record data on mental health measured by psychologists’ assessment. By contrast, we show that school starting age has no significant effect later in life by including both males and females in the analysis, using German survey data comprising self-reported mental health measures.

Note that the loss of statistical significance is not surprising given the substantial decrease in the sample size.

Two point estimates for the effect on mental health are statistically significant at the 10% level when young respondents are excluded from the estimation; however, this effect is statistically non-significant when persons older than 60 years are excluded. Moreover, the effect is always statistically non-significant when a 4-month window is used instead of a 2-month window (see Table 14 in the Appendix).

To characterize compliers relative to the entire sample, we adopted the methodology as explained in Angrist and Pischke (2009).

For instance, the smoking behavior of a person’s reference group might affect his/her own smoking behavior (endogenous effect). Moreover, an individual’s smoking behavior may be influenced by the observed socioeconomic status of the reference group (contextual effect). However, it might also be affected by the unobserved work environment that both the person and reference group share (correlated effect).

The relative age of friends is calculated by dividing the average age of friends by the respondent’s own age.

For respondents who had not yet finished their secondary education, we included their current school type as a covariate.

Elder and Lubotsky (2009) reveal that a 1-year increase in kindergarten entry age decreases the likelihood of grade retention by 13.1 percentage points in the first and second grade and by 15.5 percentage points in any grade in the first 8 years of schooling.

These studies interpret this finding as evidence for misdiagnosis of ADHD.

References

Andersen HH, Mühlbacher A, Nübling M, Schupp J, Wagner GG (2007) Computation of standard values for physical and mental health scale scores using the SOEP version of SF-12v2. Schmollers Jahrbuch 127(1):171–182

Anderson PM, Butcher KF, Cascio EU, Schanzenbach DW (2011) Is being in school better? The impact of school on children’s BMI when starting age is endogenous. J Health Econ 30(5):977–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.06.002

Anger S, Schnitzlein DD (2017) Cognitive skills, non-cognitive skills, and family background: evidence from sibling correlations. J Popul Econ 30(2):591–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0625-9

Anger S, Kvasnicka M, Siedler T (2011) One last puff? Public smoking bans and smoking behavior. J Health Econ 30(3):591–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.03.003

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (1991) Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Q J Econ 106(4):979–1014. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937954

Angrist JD, Pischke JS (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Argys LM, Rees DI (2008) Searching for peer group effects: a test of the contagion hypothesis. Rev Econ Stat 90(3):442–458

Bachmann CJ, Philipsen A, Hoffmann F (2017) ADHS in Deutschland: Trends in Diagnose und medikamentöser Therapie. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 114(9):141–148

Barua R, Lang K (2016) School entry, educational attainment, and quarter of birth: a cautionary tale of a local average treatment effect. J Hum Capital 10 (3):347–376. https://doi.org/10.1086/687599

Bedard K, Dhuey E (2006) The persistence of early childhood maturity: international evidence of long-run age effects. Q J Econ 121(4):1437–1472

Bernardi F (2014) Compensatory advantage as a mechanism of educational inequality: a regression discontinuity based on month of birth. Sociol Educ 87(2):74–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040714524258

Biewen M, Tapalaga M (2017) Life-cycle educational choices in a system with early tracking and ‘second chance’ options. Econ Educ Rev 56:80–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.11.008

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2011) Too young to leave the nest? The effects of school starting age. Rev Econ Stat 93(2):455–467

Chassin L, Presson CC, Rose JS, Sherman SJ (1996) The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood: demographic predictors of continuity and change. Health Psychol 15(6):478–484

Chorniy A, Kitashima L (2016) Sex, drugs, and ADHD: the effects of ADHD pharmacological treatment on teens’ risky behaviors. Labour Econ 43:87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.06.014

Dalsgaard S, Humlum MK, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M (2012) Relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: the role of specialist behavior. Econ Lett 117 (3):663–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.08.008

Dhuey E, Lipscomb S (2008) What makes a leader? Relative age and high school leadership. Econ Educ Rev 27(2):173–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.08.005

Dobkin C, Ferreira F (2010) Do school entry laws affect educational attainment and labor market outcomes? Econ Educ Rev 29(1):40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.04.003

Dustmann C, Puhani PA, Schönberg U (2017) The long-term effects of early track choice. Econ J 127(603):1348–1380. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12419

Eibich P (2015) Understanding the effect of retirement on health: mechanisms and heterogeneity. J Health Econ 43:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.05.001

Eide ER, Showalter MH (2001) The effect of grade retention on educational and labor market outcomes. Econ Educ Rev 20(6):563–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(00)00041-8

Elder TE, Lubotsky DH (2009) Kindergarten entrance age and children’s achievement: impacts of state policies, family background, and peers. J Hum Res 44 (3):641–683. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.44.3.641

Elder TE (2010) The importance of relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: evidence based on exact birth dates. J Health Econ 29(5):641–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.06.003

Evans WN, Morrill MS, Parente ST (2010) Measuring inappropriate medical diagnosis and treatment in survey data: the case of ADHD among school-age children. J Health Econ 29(5):657–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.07.005

Fertig M, Kluve J (2005) The effect of age at school entry on educational achievement in Germany. IZA Discussion Paper Series 1507

Fletcher J, Kim T (2016) The effects of changes in kindergarten entry age policies on educational achievement. Econ Educ Rev 50:45–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.11.004

Fredriksson P, Öckert B (2014) Life-cycle effects of age at school start. Econ J 124(579):977–1004

Gaviria A, Raphael S (2001) School-based peer effects and juvenile behavior. Rev Econ Stat 83(2):257–268

Godard M (2016) Gaining weight through retirement? Results from the SHARE survey. J Health Econ 45:27–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.11.002

Graue ME, DiPerna J (2000) Redshirting and early retention: who gets the ‘gift of time’ and what are its outcomes? Am Educ Res J 37(2):509–534. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312037002509

Grobe TG, Bitzer EM, Schwartz FW (2013) Schwerpunkt: Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörungen: ADHS, Barmer-GEK-Arztreport, Schriftenreihe zur Gesundheitsanalyse, vol 18. Siegburg

Gruber J, Zinman J (2000) Youth smoking in the U.S.: evidence and implications. NBER Working Paper 7780, National Bureau of Economic Research

Hahn J, Todd P, WVd Klaauw (2001) Identification and estimation of treatment effects with a regression-discontinuity design. Econometrica 69(1):201–209. https://doi.org/10.2307/2692190

Hölling H, Schlack R, Kamtsiuris P, Butschalowsky H, Schlaud M, Kurth BM (2012) Die KiGGS-Studie: Bundesweit repräsentative Längs- und Querschnittstudie zur Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen im Rahmen des Gesundheitsmonitorings am Robert Koch-Institut. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 55(6-7):836–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1486-3

Imbens GW, Lemieux T (2008) Regression discontinuity designs: a guide to practice. J Econ 142(2):615–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.001

Jürges H, Schneider K (2007) What can go wrong will go wrong: birthday effects and early tracking in the German school system. CESifo Working Paper 2055

Jürges H, Reinhold S, Salm M (2011) Does schooling affect health behavior? Evidence from the educational expansion in Western Germany. Econ Educ Rev 30 (5):862–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.04.002

Landersø R, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M (2016) School starting age and the crime-age profile. Econ J 127(602):1096–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12325

Lee DS, Lemieux T (2010) Regression discontinuity designs in economics. J Econ Lit 48(2):281–355

Lubotsky D, Kaestner R (2016) Do ‘skills beget skills’? Evidence on the effect of kindergarten entrance age on the evolution of cognitive and non-cognitive skill gaps in childhood. Econ Educ Rev 53:194–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.04.001

Manski CF (1993) Identification of endogenous social effects: the reflection problem. Rev Econ Stud 60(3):531–542. https://doi.org/10.2307/2298123

Manski CF (1995) Identification problems in the social sciences. Cambridge, Harvard University Press

Marcus J (2013) The effect of unemployment on the mental health of spouses – evidence from plant closures in Germany. J Health Econ 32(3):546–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.02.004

McAdams JM (2016) The effect of school starting age policy on crime: evidence from U.S. microdata. Econ Educ Rev 54:227–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.12.001

McEwan PJ, Shapiro JS (2008) The benefits of delayed primary school enrollment: discontinuity estimates using exact birth dates. J Hum Res 43(1):1–29

Morrow RL, Garland EJ, Wright JM, Maclure M, Taylor S, Dormuth CR (2012) Influence of relative age on diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Can Med Assoc J 184(7):755–762. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.111619

Mühlenweg A, Puhani PA (2010) The evolution of the school-entry age effect in a school tracking system. J Hum Res 45(2):407–438

Mühlenweg A, Blomeyer D, Stichnoth H, Laucht M (2012) Effects of age at school entry (ASE) on the development of non-cognitive skills: evidence from psychometric data. Econ Educ Rev 31(3):68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.02.004

Nam K (2014) Until when does the effect of age on academic achievement persist? Evidence from Korean data. Econ Educ Rev 40:106–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.02.002

Norton EC, Lindrooth RC, Ennett ST (1998) Controlling for the endogeneity of peer substance use on adolescent alcohol and tobacco use. Health Econ 7(5):439–453

Peña P A (2017) Creating winners and losers: date of birth, relative age in school, and outcomes in childhood and adulthood. Econ Educ Rev 56:152–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.12.001

Pfeifer G, Reutter M, Strohmaier K (2017) Goodbye smokers’ corner: health effects of school smoking bans. Ruhr Economic, Papers, 678. https://doi.org/10.4419/86788786

Powell LM, Tauras JA, Ross H (2005) The importance of peer effects, cigarette prices and tob control policies for youth smoking behavior. J Health Econ 24(5):950–968

Puhani PA, Weber AM (2007) Does the early bird catch the worm? Instrumental variable estimates of early educational effects of age of school entry in Germany. Empir Econ 32(2-3):359–386

Robertson E (2011) The effects of quarter of birth on academic outcomes at the elementary school level. Econ Educ Rev 30(2):300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.10.005

Sacerdote B (2011) Peer effects in education: how might they work, how big are they and how much do we know thus far?. In: Hanushek E A, Machin S, Woessmann L (eds) Handb econ educ, vol 3. Elsevier, pp 249–277

Salyers MP, Bosworth HB, Swanson JW, Lamb-Pagone J, Osher FC (2000) Reliability and validity of the SF-12 health survey among people with severe mental illness. Med Care 38(11):1141–1150

Schwandt H, Wuppermann A (2016) The youngest get the pill: ADHD misdiagnosis in Germany, its regional correlates and international comparison. Labour Econ 43:72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.05.018

Staiger D, Stock JH (1997) Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 65(3):557–586. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171753

Statistisches Bundesamt (2014) Mikrozensus - Fragen zur Gesundheit - Rauchgewohnheiten der Bevölkerung, Publikationen im Bereich Gesundheitszustand. Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden

Stipek D (2002) At what age should children enter kindergarten? A question for policy makers and parents. SRCD Social Policy Report 16(2):1–19

Tan PL (2017) The impact of school entry laws on female education and teenage fertility. J Popul Econ 30(2):503–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-016-0609-9

US Department of Health and Human Services (2012) Preventive tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Report, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA

Wacker M, Holle R, Heinrich J, Ladwig KH, Peters A, Leidl R, Menn P (2013) The association of smoking status with healthcare utilisation, productivity loss and resulting costs: results from the population-based KORA F4 study. BMC Health Serv Res 13:278. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-278

Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J (2007) The German Socio-economic Panel Study (SOEP) — scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch: Z Wirtschafts Sozialwissenschaften/J Appl Soc Sci Stud 127(1):139–169

Ware JEJ, Kosinski MM, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220–233

WHO (2015a) WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2015. World Health Organization

WHO (2015b) WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015: raising taxes on tobacco. World Health Organization

Xu X, Bishop EE, Kennedy SM, Simpson SA, Pechacek TF (2015) Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking: an update. Am J Prev Med 48(3):326–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.012

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas Siedler and Jan Marcus for beneficial discussions that improved this study. We further thank participants of the seminars at Universität Hamburg, Hamburg Center for Health Economics (HCHE), the 12th International German Socio-Economic Panel User Conference, and the 11th European Conference on Health Economics. We are grateful to three anonymous referees for their help and guidance.

Funding

This study has received funding from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Federal Ministry of Education and Research), project “Nicht-monetäre Erträge von Bildung in den Bereichen Gesundheit, nicht-kognitive Fähigkeiten sowie gesellschaftliche und politische Partizipation.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Junsen Zhang

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bahrs, M., Schumann, M. Unlucky to be young? The long-term effects of school starting age on smoking behavior and health. J Popul Econ 33, 555–600 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-019-00745-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-019-00745-6