Abstract

This paper investigates cross-linguistic variation in raising-to-subject constructions, proposing a unified account for the derivation of hyper-raising and standard raising. I argue that the presence or absence of these constructions in a given language can be determined without recourse to phases by independent properties of CP and TP in the language, including: (1) whether CPs or infinitival phrases are phi-goals in the language and (2) the presence of an EPP effect on T and (and how it can be satisfied). I show that variation in these factors can capture a number of different raising profiles found cross-linguistically, including the hyper-raising pattern found in Zulu and Uyghur, the absence of raising in Makhuwa and Matengo, and the more familiar pattern of English.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All otherwise unsourced English data in this paper reflects my own native speaker intuitions.

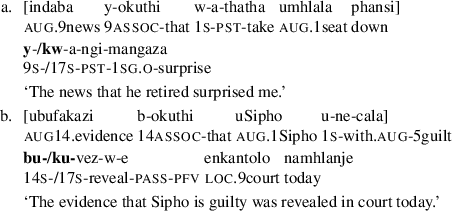

All unsourced Zulu data in this paper was collected by me in consultation with native speakers of Durban Zulu in Durban, South Africa, in 2011, 2012, and 2015. Bantu agreement is for noun class. Zulu has 15 of the 22 Bantu noun classes (numbers 1–11, 14–17); even numbers are typically plurals of odd-numbered classes. A nominal agrees if the noun class marked on the noun matches the number of the agreement marker. I mark class 1 subject agreement as 1s, but 1sg.s for 1st person singular, etc. Other abbreviations follow the Leipzig Glossing Rules with the addition of the following: assoc associative, aug augment vowel, prt participial agreement, ya (present tense) disjoint marker.

Though see e.g. Hornstein (1999) for arguments that obligatory control is an instantiation of raising. I set aside this issue here.

Note, though, that only adjectival—and for some speakers, nominal—small clauses can combine with raising predicates in English. As a number of authors have discussed, verbal small clauses are ungrammatical in this environment: *John seems leave/leaving (e.g. Williams 1983, 1984; Basilico 2003) I will return to this issue in Sect. 5.2.

Ura’s full list includes at least two languages that he mischaracterizes as permitting hyper-raising, Persian and Acehnese, which I omit from the table here. Karimi (2005, 2008) provides evidence that the apparent hyper-raising construction in Persian is in fact an instance of topicalization, rather than of A-movement. Ura provides a purported Acehnese example in (2.9a) that appears to indicate that the subject of a finite embedded clause has raised to become an agreeing matrix subject in a passivized ECM construction; Ura refers to Durie (1985), which does not contain his reported examples, and does not provide argumentation for his analysis of the construction as involving A-movement out of a finite embedded clause. As Legate (2012, 2014) demonstrates, Acehnese has restructuring predicates that permit a long passive, yielding a string similar to the one Ura reports, where the embedded subject appears in matrix subject position. These constructions differ in two crucial respects from Ura’s characterization: first, as Legate shows, restructuring (and long passive) is only possible with embedded clauses no larger than vP; second, agreement in the matrix clause still tracks the matrix agent—and not the long-passivized argument (thanks to Julie Legate for noting these issues with Acehnese). Given these issues, the other languages in Ura’s sample should be scrutinized to determine whether they are in fact clear examples of a hyper-raising pattern.

Carstens (2011) suggests that DPs in Bantu languages are endowed with valued, uninterpretable phi-features, which causes them to remain Active regardless of how many times they Agree; on such an approach, hyper-raising is the straightforward result of the embedded subject being the closest Active goal to the matrix phi-probe, but makes two assumptions—that hyper-raising is obligatory and that it occurs out of bare TP complements—that cannot hold for the cases discussed in this paper.

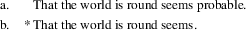

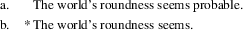

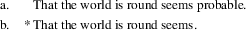

It has been argued that these constructions might in fact involve a CP in topic position, rather than Spec,TP (e.g. Koster 1978; Alrenga 2005; Londahl 2014). For our pre-theoretical understanding of the EPP, it is simply enough to note that when a CP appears in preverbal position, no other element is required to fill Spec,TP. As we’ll see in Sect. 5, it is likely that preverbal CPs are not bare CPs, but are housed inside DP structure (Rosenbaum 1967; Davies and Dubinsky 2009; Hartman 2012a.o.).

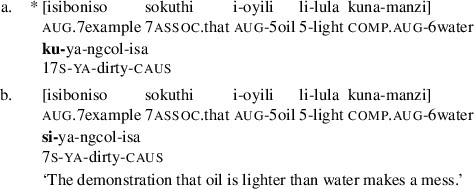

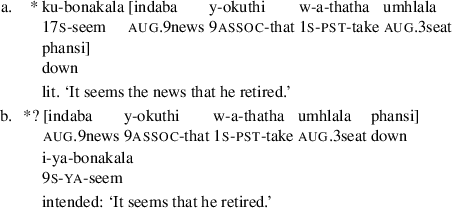

Movement to Spec,TP affects the interpretation of the subject (see e.g. Buell 2005; Cheng and Downing 2009, 2014; Halpert 2012; Zeller 2008). Roughly, vP-internal subjects typically receive focus or are part of a presentational focus construction, while vP-external subjects cannot be narrow focus. Cheng and Downing (2014) further suggest that preverbal subjects carry an existence presupposition. I abstract away from these interpretive issues here and instead focus on the agreement consequences that correlate with syntactic position. In Sect. 4.3 we will see a consequence of these effects for the behavior of infinitival complements of bonakala.

Buell (2007) distinguishes between “semantic” and “formal” locative inversion. In formal locative inversion, the fronted phrase retains its locative morphology and agreement is either with the locative morphology itself or is expletive (but still not with the low subject). Semantic locative inversion, by contrast, involves a DP that receives a locative interpretation, but does not display locative morphology when in preverbal subject position, as illustrated in (31) above.

Many speakers who reject this type of construction will spontaneously fix it by adding a head nominal and turning the phrase into a complex DP (Halpert 2015). See the Appendix for details of this construction and how it might present a parallel to the raising case discussed here.

There is systematically no segmental reflex of the disjoint morpheme, ya in positive present contexts, under negation, which is why the fronted object clause in (48) controls agreement without the appearance of ya (see Buell 2005).

There is, in fact, a second possible derivation that would yield (50a): where T first probes the embedded clause, and then inserts an expletive to satisfy the EPP, diverging from the derivation described for (50b) below.

There are other approaches that also result in a single probe Agreeing with multiple goals (e.g. Hiraiwa 2001; Boeckx 2003; Henderson 2006). In the construction under discussion, it is crucial the probing not be simultaneous; even if we separate the operation into Match and Agree, along the lines of Boeckx (2003), we would fail to capture the fact that phi-agreement in Zulu can track the CP (first Agree operation) even when the embedded subject moves. In other words, agreement does not simply reflect the closest goal at the end of the derivation. I therefore continue with Deal’s formalization, though it is possible that other approaches could be made to yield the same result.

A reviewer asks whether hyper-raising-to-object is also available in Zulu by the same mechanism, given that the language has object agreement that can target clauses. The answer is yes, raising-to-object out of finite clauses is possible, but as Halpert and Zeller (2015) discuss, it does not appear that the mechanism for this raising is object agreement. Due to the differences between the two constructions—and between the properties of subject and object agreement in Zulu more generally—this question is beyond the scope of this paper. I refer the reader to Halpert and Zeller (2015) for more discussion.

Recall from the previous subsection that overt subjects of infinitives are expressed via the associative construction.

We can see evidence for the size of the nominalized clauses in the case-marking possibilities: the NP-sized nominalizations are unable to bear overt case marking, while DP-sized nominalizations can be case-marked.

Another difference between the Uyghur examples Asarina discusses and the Zulu patterns discussed here is that the relevant optionality in morphological spell out in Zulu involves different types of third person—changing only in noun class—while the Uyghur patterns involve changes in the person features of the clause vs. embedded subject. Initial evidence on the behavior of first and second person in Zulu raising constructions is mixed, so I set aside this issue for now, but it is possible that the type of phi-features involved in the agreement operations may play a role in determining the morphological possibilities.

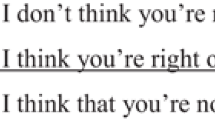

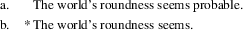

Along these lines, we might also wonder whether Hartman’s (2012) last resort DP structure ever applies to embedded CPs in raising contexts. It seems that we do find CP-fronting in English exactly where a DP argument would be permitted, as well as a CP, as a complement to the predicate, as Hartman would predict (Williams 1980; Webelhuth 1992; Alrenga 2005; Moulton 2009a.o.):

-

(72)

-

(73)

-

(72)

References

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1998. Parametrizing Agr: Word order, V-movement and EPP-checking. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16: 491–539.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1999. Raising without infinitives and the nature of agreement. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 18, eds. Sonya Bird, Andrew Carnie, Jason Haugen, and Peter Norquest, 15–25. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Alrenga, Peter. 2005. A sentential subject asymmetry in English and its implications for complement selection. Syntax 8: 175–207.

Asarina, Alya. 2011. Case in Uyghur and beyond. PhD diss., MIT.

Baker, Mark. 2003. Lexical categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark. 2008. The syntax of agreement and Concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Basilico, David. 2003. The topic of small clauses. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 1–35.

Boeckx, Cedric. 2003. Islands and chains: Resumption as stranding. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bošković, Željko. 2002. Expletives don’t move. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 32, ed. Masako Hirotani. Vol. 1, 21–40.

Bresnan, Joan. 2001. Lexical-functional syntax. Hoboken: Blackwell Sci.

Buell, Leston. 2005. Issues in Zulu morphosyntax. PhD diss., UCLA.

Buell, Leston. 2007. Semantic and formal locatives: Implications for the Bantu locative inversion typology. SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 15: 105–120.

Buell, Leston. 2012. Class 17 as a non-locative noun class in Zulu. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 33: 1–35.

Carstens, Vicki. 2001. Multiple agreement and case deletion: Against phi-(in)completeness. Syntax 4: 147–163.

Carstens, Vicki. 2005. Agree and EPP in Bantu. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 23: 219–279.

Carstens, Vicki. 2011. Hyperactivity and hyperagreement in Bantu. Lingua 121: 721–741.

Carstens, Vicki, and Michael Diercks. 2013a. The great escape: Raising out of finite clauses in Bantu languages. Handout from talk given at UCSC Colloquium, 2013.

Carstens, Vicki, and Michael Diercks. 2013. Parameterizing case and activity: Hyperraising in Bantu. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 40, eds. Seda Kan, Claire Moore-Cantwell, and Robert Staubs. 99–118. Amherst: GLSA.

Cheng, Lisa, and Laura J. Downing. 2014. Indefinite subjects in Durban Zulu. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 57: 5–25.

Cheng Lisa Lai-Shen, and Laura J. Downing. 2009. Where’s the topic in Zulu? The Linguistic Review 26: 207–238.

Chomsky, Noam. 1964. A transformational approach to syntax. In The structure of language, eds. Jerry Fodor and Jerry Katz, 211–245. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Chomsky, Noam. 1982. Some concepts and consequences of the theory of government and binding. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–156. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in linguistics, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Collins, Chris. 2004. The agreement parameter. In Triggers, eds. Anne Breitbarth and Henk van Riemsdijk, 115–136. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Contreras, Heles. 1991. On resumptive pronouns. In Current studies in Spanish linguistics, eds. Hector Campos and Fernando Martínez-Gil, 143–164. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Creissels, Denis, and Daniele Godard. 2005. The Tswana infinitive as a mixed category. In 12th international conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG), ed. Stefan Müller, 70–90.

Davidson, Donald. 1967. The logical form of action sentences. In The logic of decision and action, ed. Nicholas Rescher, 81–95. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press.

Davies, William D., and Stanley Dubinsky. 2009. On the existence (and distribution) of sentential subjects. In Hypothesis A/Hypothesis B: Linguistic explorations in honor of David M. Perlmutter, eds. Donna Gerdts, John Moore, and Maria Polinsky, 111–128. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Deal Amy Rose. 2015. Interaction and satisfaction in phi-agreement. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 45, eds. Thuy Bui and Deniz Ozyildiz. Vol. 1, 179–192. Amherst: GLSA.

Diercks, Michael. 2012. Parameterizing case: Evidence from Bantu. Syntax 15, 253–286.

Durie, Mark. 1985. A grammar of Acehnese on the basis of a dialect of North Aceh. Dordrecht: Foris.

Fernández-Salguiero, Gerardo. 2005. Agree, the EPP-F and further-raising in Spanish. In Experimental and theoretical approaches to Romance linguistics, eds. Randall Gess and Edward Rubin, 97–107. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Fernández-Salguiero, Gerardo. 2008. The Case-F valuation parameter in Romance. In The limits of syntactic variation, ed. Theresa Biberauer, 295–310. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Ferreira, Marcelo. 2004. Imperfectives and plurality. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 14, ed. Robert B. Young, 74–91. Cornell University: CLC Publications.

Ferreira, Marcelo. 2009. Null subjects and finite control in Brazilian Portuguese. In Minimalist essays on Brazilian Portuguese syntax, ed. Jairo Nunes. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Halpert, Claire. 2012. Argument licensing and agreement in Zulu. PhD diss., MIT.

Halpert, Claire. 2015. Argument licensing and agreement. New York: Oxford University Press.

Halpert, Claire, and Jochen Zeller. 2015. Double dislocation and raising-to-object in Zulu. The Linguistic Review 32: 475–513.

Hartman, Jeremy. 2012. Varieties of clausal complementation. PhD diss., MIT.

Henderson, Brent. 2006. Multiple agreement and inversion in Bantu. Syntax 9: 275–289.

Higginbotham, James. 1983. Logical form, binding, and nominals. Linguistic Inquiry 14: 395–420.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2001. Multiple Agree and the defective intervention constraint in Japanese. In Harvard University MIT Student Conference (HUMIT) 2000, eds. Ora Matushansky, Albert Costa, Javier Martin-Gonzalez, Lance Nathan, and Adam Szczegielniak, 67–80. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Hornstein, Norbert. 1999. Movement and control. Linguistic Inquiry 30: 69–96.

Hornstein, Norbert, Ana Maria Martins, and Jairo Nunes. 2008. Perception and causative structures in English and European Portuguese: ϕ-feature agreement and the distribution of bare and prepositional infinitives. Syntax 11: 198–222.

Iatridou, Sabine. 1993. On nominative case assignment and a few related things. In Papers on case and agreement 2, ed. Colin Phillips. Vol. 19 of MIT working papers in linguistics, 175–196 Cambridge: MIT.

Iatridou, Sabine, and David Embick. 1997. Apropos pro. Language 73: 58–78.

Ishihara, Yuki. 2009. A note on the infinitival complements of perception verbs. Linguistic Research 25: 103–112.

Julien, Marit. 2002. Syntactic heads and word formation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Karimi, Simin. 2005. A minimalist approach to scrambling: Evidence from Persian. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Karimi, Simin. 2008. Raising and control in Persian. In Aspects of Iranian linguistics, eds. Simin Karimi, Donald Stilo, and Vida Samiian, 177–208. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

Kayne, Richard. 2014. Why isn’t this a complementizer? In Functional structure from top to toe: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Peter Svenonius, Vol. 9, 188–231. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koster, Jan. 1978. Why subject sentences don’t exist. In Recent transformational studies in European languages, ed. Samuel Jay Keyser. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2012. Subjects in Acehnese and the nature of the passive. Language 88: 495–525.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2014. Voice and v: Lessons from Acehnese. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Londahl, Terje. 2014. Sentential subjects: topics or real subjects. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 31, ed. Robert E. Santana-LaBarge, 315–324. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Martins, Ana Maria, and Jairo Nunes. 2005. Raising issues in Brazilian and European Portuguese. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 4: 53–77.

Moulton, Keir. 2009. Natural selection and the syntax of clausal complementation. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Moulton, Keir. 2015. CPs: Copies and compositionality. Linguistic Inquiry 46: 305–342.

Nyembezi, C.L. Sibusiso. 1991. Uhlelo lwesiZulu, 5th edn. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter Publishers Ltd.

Ordóñez, Francisco. 1997. Word order and clause structure in Spanish and other Romance languages. PhD diss, City University of New York.

du Pessis, Jacobus A. 2010. The expletive in the African languages of South Africa. Stellenbosch University.

Picallo, M. Carme, 2002. Abstract agreement and clausal arguments. Syntax 5: 116–147.

Pires, Acrisio. 2006. The minimalist syntax of defective domains. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Polinsky, Maria. 2013. Raising and control. In The Cambridge handbook of generative syntax, ed. Marcel den Dikken. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Polinsky, Maria, and Eric Potsdam. 2006. Expanding the scope of control and raising. Syntax 9: 171–192.

Polinsky, Maria, and Eric Potsdam. 2011. Diagnosing covert A-movement. Available as lingbuzz/001232. Accessed 9 March 2018.

Postal, Paul. 1970. On coreferential complement subject deletion. Linguistic Inquiry 1: 439–500.

Postal, Paul. 1974. On raising. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Postal, Paul. 2004. Skeptical linguistic essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Preminger, Omer. 2011. Agreement as a fallible operation. PhD diss, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures. In Linguistic Inquiry Monograph, Vol. 68. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rackowski, Andrea, and Norvin Richards. 2005. Phase edge and extraction: A Tagalog case study. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 565–599.

Richards, Norvin. 2016. Contiguity theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Roberts, Ian, and Anna Roussou. 2003. Syntactic change: A minimalist approach to grammaticalisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rodrigues, Cilene. 2004. Impoverished morphology and A-movement out of case domains. PhD diss., University of Maryland

Rosenbaum, Peter S. 1967. The grammar of English predicate complement constructions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sabelo, Nonhlanhla O. 1990. The possessive in Zulu. Master’s thesis, University of Zululand, KwaDlangezwa, South Africa.

Slattery, Hugh. 1981. Auxiliary verbs in Zulu. Occasional papers of the Department of African Languages, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa.

Ura, Hiroyuki. 1994. Varieties of raising and the feature-based bare phrase structure theory. In MIT occasional papers in linguistics, Vol. 7, Cambridge: MITWPL.

van Urk, Coppe. 2015. A uniform syntax for phrasal movement: A Dinka Bor case study. PhD diss., MIT.

van Urk, Coppe, and Norvin Richards. 2015. Two components of long-distance extraction: Successive cyclicity in Dinka. Linguistic Inquiry 46: 113–155.

Villa-Garcia, Julio. 2013. On the status of preverbal subjects in Spanish: Evidence for a dedicated subject position. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 42, eds. Stefan Keine and Shayne Sloggett, 245–256. Amherst: GLSA.

de Vries, Mark. 2006. The syntax of appositive relativization: On specifying coordination, false free relatives, and promotion. Linguistic Inquiry 37: 229–270.

van der Wal, Jenneke. 2009. Word order and information structure in Makhuwa-Enahara. PhD diss., Universiteit Leiden.

van der Wal, Jenneke. 2012. Subject agreement and the EPP in Bantu agreeing inversion. Cambridge Occasional Papers in Linguistics 6: 201–236.

van der Wal, Jenneke. 2015. Evidence for abstract Case in Bantu. Lingua 165: 109–132.

Webelhuth, Gert. 1992. Principles and parameters of syntactic saturation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, Edwin. 1980. Predication. Linguistic Inquiry 11: 203–238.

Williams, Edwin. 1983. Against small clauses. Linguistic Inquiry 14: 287–308.

Williams, Edwin. 1984. There-insertion. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 131–154.

Yoneda, Nobuko. 2011. Word order in Matengo: Topicality and information roles. Lingua 121: 754–771.

Zeller, Jochen. 2006. Raising out of finite CP in Nguni: The case of fanele. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 24: 255–275.

Zeller, Jochen. 2008. The subject marker in Bantu as an antifocus marker. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 38: 221–254.

Zeller, Jochen. 2012. Object marking in Zulu. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 30: 219–325.

Zeller, Jochen. 2013. Locative inversion in Bantu and predication. Linguistics 51: 1107–1146.

Zwart, C. Jan-Wouter. 1997. Morphosyntax of verb movement: A minimalist approach to the syntax of Dutch. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all of my Zulu consultants for help with the Zulu data in this paper; in particular, I’m grateful to Mthuli Percival Buthelezi, Mpho Dlamini, Monwabisi Mhlophe, and the Katamzi family for their continued time and patience over the years. Thanks as well to Vicki Carstens, Michael Diercks, Julie Legate, David Pesetsky, Jenneke van der Wal, Jochen Zeller, three anonymous reviewers, and audiences at GLOW, WCCFL, UC Santa Cruz, UW-Milwaukee, McGill, MIT, and the University of KwaZulu-Natal for helpful feedback and discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Sentential subjects and complex DPs

Appendix: Sentential subjects and complex DPs

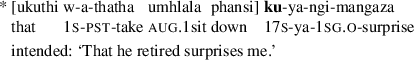

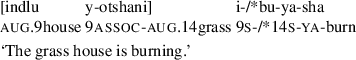

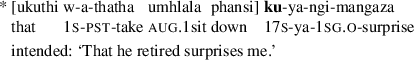

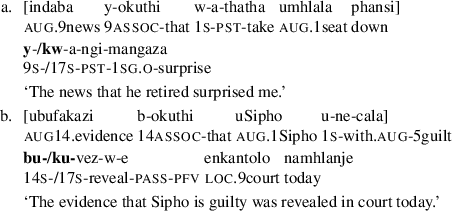

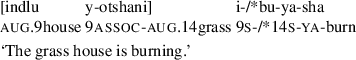

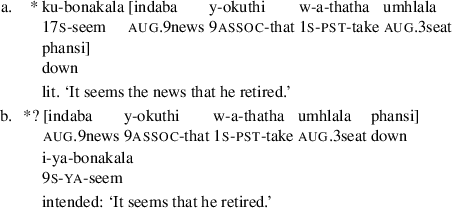

Recall from Sect. 4 that Zulu does not permit ukuthi CPs in Spec,TP position:

-

(80)

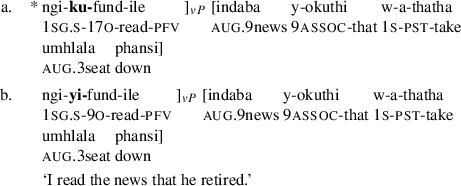

Many speakers who reject this type of construction will spontaneously fix it by adding a head nominal and turning the phrase into a complex DP. Remarkably, these complex DP subjects do not require agreement with the head nominal. Instead, either agreement with the nominal or ku- agreement is grammatical:

-

(81)

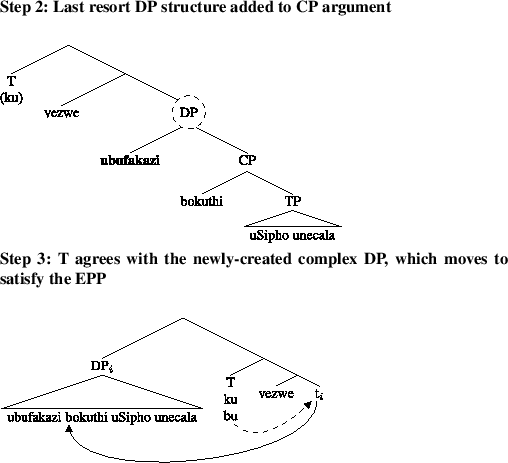

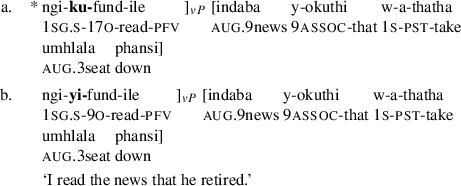

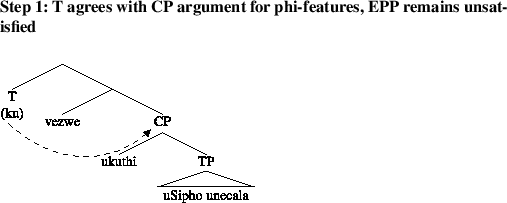

I argue in Halpert (2012, 2015) that the ku- agreement in (81) is not an instance of expletive agreement, but rather a reflection of true phi-agreement with the CP component of the complex DP, claiming that this is possible because the NP and CP components are equidistant from the T probe, along the lines of appositive structure (e.g. de Vries 2006). I keep this general conclusion here—that the ku- in these constructions is T agreement with the CP—but argue for a different structure, based on the observation above that sentential CPs are disallowed in Zulu. The status of sentential subjects cross-linguistically is contentious; a number of researchers have suggested that even in languages like English, where we have the surface appearance of CPs in subject position, do not allow CPs to appear in Spec,TP—and that these constructions either involve a CP in topic position (e.g. Koster 1978; Alrenga 2005; Londahl 2014) or additional DP structure on the CP (e.g. Rosenbaum 1967; Davies and Dubinsky 2009; Hartman 2012). In particular, Hartman (2012) argues that clauses in Spec,TP always have DP structure and that a DP-shell may be inserted as a “last resort,” post-cyclically, in order to allow a clausal argument to raise to Spec,TP. While Zulu clearly does not have the type of covert DP structure that Hartman argues is available in English, we can imagine that at least some complex subject DPs in Zulu are created by the same process, but with the addition of an overt DP shell.

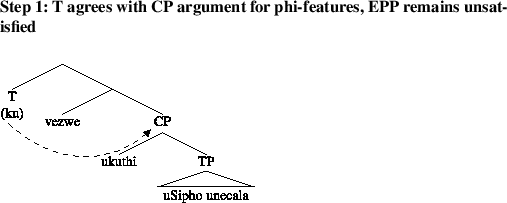

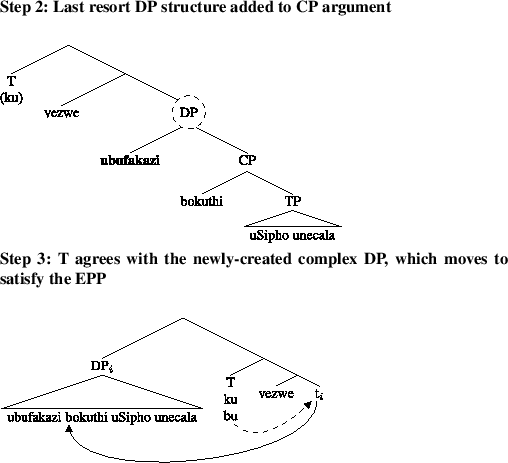

On this approach, a potential derivation for a complex DP subject would be as follows: First, T probes and agrees with the CP argument, which cannot move to Spec,TP, leaving the EPP unsatisfied. Then, Hartman’s last resort operation applies to add an overt DP shell to the CP argument. Since the EPP in Zulu must be satisfied by an agreeing element, T may probe a second time, as Halpert (2012, 2015) argues, to find the complex DP that has been created. As a result of this second Agree operation, the complex DP will move to Spec,TP to satisfy the EPP. While Hartman (2012) assumes for languages like English that agreement with T only results when DP structure is added—and not with the bare CP—in Zulu we have reason to think that agreement occurs at both stages: we saw that CPs bore phi-features that surface in object agreement constructions and we can understand the ku- agreement that surfaces with complex DP subjects as the result of the first Agree operation. In other words, when complex DPs are created via last resort in Zulu, T agrees with first the CP component and then the DP component, and can morphologically realize the outcome of either operation.

-

(82)

-

(83)

Hartman (2012) argues that this type of operation is only available when the clausal argument needs to move to Spec,TP. Object CPs in English, by contrast, never show evidence for added covert DP structure. We find this same type of asymmetry in Zulu: speakers report that object marking with a complex DP must match the nominal component—and cannot be the ku- that we would expect if agreement with the clause were available in every complex DP:

-

(84)

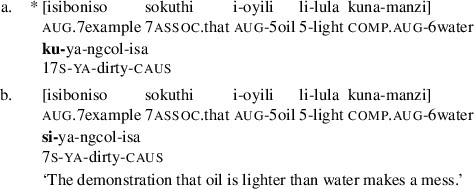

Similarly, in constructions with a complex DP argument where a clausal argument would be disallowed, ku- agreement is ungrammatical even in subject position:

-

(85)

On the approach outlined above, the absence of ku- agreement in (84) and (85) is expected because in these situations the DP-shell must have been present from the start, rather than added via last resort. By contrast, the equidistant structure for complex DPs I proposed in Halpert (2012, 2015) does not distinguish between these environments and thus cannot capture these asymmetries. On this approach, we can also take seriously the associative morphology controlled by the nominal component that appears on the CP. As Sabelo (1990) and Halpert (2012) discuss, associate morphology can introduce nominal modifiers; viewing the complex DP construction in Zulu as a case of nominal modification (along the lines of Moulton 2009, 2015), rather than as an appositive, fits with this picture. Since the cases of ku- agreement arise when DP structure is added during the derivation, the fact that associate constructions do not freely permit agreement higher with the modifying element is expected.

-

(86)

While both the hyper-raising process discussed in Sect. 4 and the complex DP process discussed above have the same logic—T probes a second time after agreeing with a CP—the outcome is different in each type of construction. How can we account for these differences? Crucially, as Hartman (2012) discusses, the last-resort DP shell operation can apply only in instances where a DP argument is possible. As we saw in Sect. 4, raising predicates do not permit DP arguments (when such predicates combine with a DP argument, they receive a different interpretation). Thus the DP shell operation is unavailable in the raising cases:

-

(87)

We can think of the difference between complex DP subjects and hyper-raised subjects, then, in terms of what happens in between the two probing operations: with complex DPs, the additional DP structure will create a new goal that contains the CP, which results in movement of the entire complex DP. In the hyper-raising cases, no extra structure is added, so when T probes a second time it will find a lower goal inside the CP.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Halpert, C. Raising, unphased. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 123–165 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9407-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9407-2