Abstract

According to one argument for Animalism about personal identity, animal, but not person, is a Wigginsian substance concept—a concept that tells us what we are essentially. Person supposedly fails to be a substance concept because it is a functional concept that answers the question “what do we do?” without telling us what we are. Since person is not a substance concept, it cannot provide the criteria for our coming into or going out of existence; animal, on the other hand, can provide such criteria. This argument has been defended by Eric Olson, among others. I argue that this line of reasoning fails to show Animalism to be superior to the Psychological Approach, for the following two reasons: (1) human animal, animal, and organism are all functional concepts, and (2) the distinction between what something is and what it does is illegitimate on the reading that the argument needs.

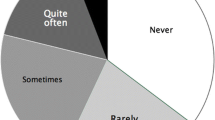

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Olson (1997).

Carter (1982) also engages this issue, and also argues that person is not a substance concept, though he does not defend animalism.

See Nozick (1981).

See Nagel (1986).

Although, as is well-known, Parfit has argued that identity is not “what matters” in survival. Still, even Parfit agrees that identity usually contingently coincides with what matters.

Shoemaker’s (1962) “Brown and Brownson” case is the first brain transfer thought experiment. It is a contemporary version of Locke’s (1995/1693) much earlier soul transfer thought experiment. The overwhelming intuitive response to both thought experiments is that a person follows his or her psychology (whether that psychology is grounded in a soul, brain, or something else), even if that psychology leaves one’s own body. Olson (1997) believes that the brain transfer case is neutral between the Psychological Approach and Animalism, and thus proposes a cerebrum transfer case. If we believe that we go where our cerebrum goes, that allegedly supports the Psychological Approach, although Olson argues that it only supports a Psychological Approach to what matters—not identity.

My interpretation of Olson here is based on what he says in Chap. 2 and p. 121 of The Human Animal.

This use of ‘person’ appears to be a descendent of the Lockean conception of ‘person’ as a forensic term, perhaps with some modifications Locke (1995/1693).

Olson (1997, p. 130).

DeGrazia (2005).

DeGrazia (2005, pp. 30–31). The PA, he says, could just accept the de dicto thesis that psychological continuity is required in order for one to continue to exist qua person. In his (1997), Olson seems to think that all versions of the PA are committed to person essentialism, but he qualifies this to “nearly all” in his (1999).

If we are allowing for the possibility of adopting the de dicto thesis, then what follows is that all versions of versions of PA that rely on person essentialism are false.

Wiggins (2001, p. 21).

Olson (1997, p. 32.

Olson (1997, pp. 32–36).

Olson (1997, p. 35), emphasis added.

Olson (1997, pp. 34–35), emphasis of ‘dispositional’, ‘functional’, and ‘intrinsic structures’ added.

According to Snowdon (1990) “Surely if we ask to what entities the functional predicate (person), as elucidated by Locke, does apply, the answer we all want to give is—a certain kind of animal, namely human beings” (p. 90). DeGrazia (2005) claims that “Rather than regarding personhood as a basic kind, we should regard it as comprising a set of capacities that things of different basic kinds might achieve. On this view, personhood represents merely a phase of our existence” (p. 49).

Olson (1997): 121.

ibid.

Olson (1997, p. 36).

Indeed, DeGrazia is deliberately noncommittal regarding the precise boundaries of our kind; he insists only that it is biological (2005, pp. 48–49. However, since organism, animal, and human organism are the most plausible of these candidate biological kinds, and since it would be tedious to survey all the other candidates, I shall confine my discussion to these three kinds.

Sober (2000, p. 152).

Rob Wilson (2005) also defines ‘organism’ largely in terms of functional features. He contends that ‘organism’ is best defined by a homeostatic property cluster, in which many of the important properties are functional.

Olson (1997, p. 130), emphasis added.

Hershenov (2005, pp. 49–50), emphasis in original.

One might wonder whether this capacity (and perhaps some of the others definitive of animals, organisms, and species) is grounded in an intrinsic, structural feature, such as DNA. (Thanks to Alan Sidelle for suggesting this to me.) That certainly is a live possibility, but this sort of empirical consideration is just as applicable to person. That is to say, if something like Nagel’s (1986) “same brain” view is right, then the property of personhood is indeed grounded in an intrinsic, structural property, namely, the structure of the human brain. So, while I certainly do not mean to presuppose that there is no structure underlying the capacity to reproduce fertile offspring with other individuals, I also think that one should not presuppose that there is no structure underlying the capacity for personhood. So I think that animalism and the Psychological View are on approximately equal footing in this matter.

See Sober (2000), Chap. 6.

Hirsch (1982).

For example, see Hawking (1988).

Greene (1999, p. 11).

References

Aristotle, Categories.

Aristotle, Metaphysics.

Campbell, N., Mitchell, L., & Reece, J. (1997). Biology: Concepts and connections (2nd ed.). New York: Benjamin/Cummins.

Carter, W. R. (1982). Do zygotes become people? Mind, 361, 77–95.

DeGrazia, D. (2005). Human identity and bioethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Greene, B. (1999). The elegant universe. New York: Vintage Books.

Hawking, S. (1988). A brief history of time. New York: Bantam Books.

Hershenov, D. (2005). Do dead bodies pose a problem for biological approaches to personal identity? Mind, 114(453), 31–59.

Hirsch, E. (1982). The concept of identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1976). Survival and identity. In A. Rorty (Ed.), The identities of persons. Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Locke, J. (1995/1693). An essay concerning human understanding. New York: Prometheus Books.

McMahan, J. (2002). The ethics of killing: Problems at the margins of life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merricks, T. (2001). Objects and persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Molnar, G. (2003). Powers: A study in metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nagel, T. (1986). The view from nowhere. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Noonan, H. (1989). Personal identity. London: Routledge.

Nozick, R. (1981). Philosophical explanations. Cambridge, Mass: Belnap/Harvard University Press.

Olson, E. (1997). The human animal. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Olson, E. (1999). Reply to Lynne Rudder Baker. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 69(1), 161–162.

Olson, E. (2007). What are we? A study in personal ontology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shoemaker, S. (1962). Self-knowledge and self-identity. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Shoemaker, S. (1984). Personal identity: A materialist’s account. In S. Shoemaker & R. Swinburne (Eds.), Personal identity (pp. 67–132). Oxford: Blackwell.

Snowdon, P. F. (1990). Persons, animals, and ourselves. In C. Gill (Ed.), The person and the human mind. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sober, E. (2000). Philosophy of biology (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Van Inwagen, P. (1990). Material beings. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Wallace, R. A. (1997). Biology: The world of life (7th ed.). New York: Benjamin/Cummins.

Wiggins, D. (1967). Identity and spatiotemporal continuity. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wiggins, D. (1980). Sameness and substance. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Wiggins, D. (2001). Sameness and substance renewed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, R. (2005). Genes and the agents of life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

For valuable feedback on this article, I would like to thank Mark Anderson, Holly Kantin, Carolina Sartorio, Eric Stencil, and especially Alan Sidelle.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nichols, P. Substance concepts and personal identity. Philos Stud 150, 255–270 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9412-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9412-8